Classic Album: The Lexicon Of Love – ABC

By Ian Peel | February 25, 2015

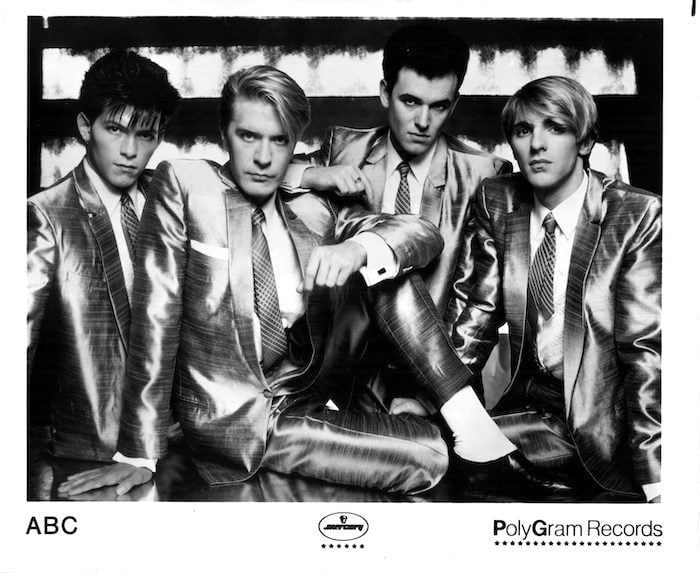

Released in 1982, ABC’S Trevor Horn-Produced debut album The Lexicon Of Love came like a bolt out of the blue, mixing futuristic funk with retro cool. It also marked the beginning of the end for the original ABC line-up as Ian Peel explains…

![]()

The summer of 1982 was a difficult time for Britain, with war raging in the Falklands and NHS workers striking for better pay at home.

Released against this backdrop, ABC’s debut long-player, The Lexicon Of Love, provided the perfect antidote. Slick, suave and stuffed full of singalong tunes, it was music to let your hair down to.

The album – with the help of its three classic singles, the band’s über-cool image (think futuristic Rat Pack) and a world tour that boasted all the glitz and glamour of a West End show – catapulted ABC to global superstardom.

For those four lads with immaculate hair and sharp, shiny suits, it all seemed so effortless – however, in truth, it wasn’t all plain sailing.

Surprisingly for an album so full of life and lustre, The Lexicon Of Love’s roots can be traced back to the dismal, post-industrial landscape of late-1970s Sheffield.

As Eve Wood would chronicle in her 2001 documentary, Made In Sheffield, dole and desperation were rife among young people in the city, prompting many to consider a career in music to enhance their prospects.

The “do it yourself” nature of the punk movement had taught kids that anyone could pick up an instrument and dig themselves out of the doldrums.

One of the leading lights of Sheffield’s music scene at that time was Stephen Singleton. In 1978, he and his friend Mark White formed a synth-pop group called Vice Versa.

And to get their music heard, Singleton also set up his own label, Neutron Records. As synth-pop goes, Vice Versa were more Throbbing Gristle than Soft Cell, creating an hypnotic groove that somehow gelled with their on-stage kaleidoscope of film and TV projections.

It wasn’t long before the band attracted the attention of Martin Fry, a Manchester-born Sheffield University student who’d set up his own music fanzine, Modern Drugs.

Fry arranged an interview with Vice Versa, during which he was invited to join the group. A few gigs (including a supporting slot for fellow Sheffield outfit The Human League) and modestly circulated singles later, Singleton, White and Fry took the decision to head off in an unashamedly melodic and melodramatic new direction.

By now, a new movement was blossoming. Labelled New Romanticism by the media, it was characterised by flamboyant costumes, carefully coiffeured hairstyles and an attitude that could best be described as hedonistic.

The soundtrack to this movement was funky, synthetic pop inspired by the disco sound that had emerged from the States a few years earlier.

Vice Versa, now renamed ABC, embraced the movement with open arms. To tie in with their more mainstream direction, Fry took on full-time frontman duties, quickly revealing a talent for lyric-writing that combined dry wit with heart-tugging romance.

In 1981, the new-look band released their debut single, Tears Are Not Enough, on their own label, reaching number 19 in the UK charts.

The B-side was Alphabet Soup, which saw Fry introducing one band member in each verse. By this time, White had switched from keyboards to guitar: “Am I right or am I wrong? You’ll find this Mark where the beat goes on. Six strings at his disposal, 60s soul in his holdall.”

And Singleton had moved from keyboards to saxophone: “Now, sax equals sex equal sax. Which makes Stephen pornographic.”

The band could’ve carved a decent career for themselves along those lines: sexy lyrics; sun-drenched sax melodies; modest chart success. After all, it worked for Modern Romance.

It was the decision to enrol Trevor Horn as producer of their debut album that took ABC to a whole new level. With his maverick approach to technology and musicianship, Horn was on a roll and had enjoyed massive hits with Yes, Dollar and The Buggles.

“The first track we worked on was Poison Arrow,” says Horn. “When they first played it to me, it was like a live band. They played it quite well because they were pretty good musicians, but I said,‘Is that what you want or do you want it better?’

“And Martin Fry said, ‘I want it as good as it can possibly be.’I said, ‘If you want it as good as it can possibly be, we’ll have to start again. And this is what I propose we do…’”

What Horn proposed was to break the entire group’s sound down to single notes, sample each and every one – every drum hit and every guitar chord – then sequence and stitch them back together.

The resulting sound retained the band’s raw funk but coated it in a glorious sheen and a razor-sharp syncopation the likes of which had never been heard before.

Horn then fleshed out the sound, bringing in a full orchestra under the leadership of Anne Dudley, sampling and programming by JJ Jeczalik and sound engineering by Gary Langan.

Those three, along with Horn and Paul Morley, would form Art Of Noise the following year. Released as ABC’s second single, Poison Arrow was received warmly by music fans and critics, peaking at number four in the UK chart.

A potent combination of soulful jazz and sorrowful lyrics, it was accompanied by a cinematic video that saw Fry honing his acting skills in his trademark gold-lamé suit alongside the impossibly named British B-movie starlet Lisa Vanderpump.

The track also features one of the most dramatic breakdowns in the history of pop, with Fry uttering the line, “I thought you loved me, but it seems you don’t care.” To which a breathless female voice returns, “I care enough to know that I could never love you.”

That female voice belongs to Gary Langan’s then-girlfriend, Karen Clayton, who went on to provide another classic spoken-word moment of 1980s pop when she intoned, “To be in England in the summertime. With my love. Close to the edge,” on Art Of Noise’s single Close (To The Edit).

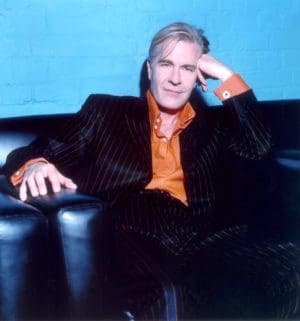

Right from the word go, the media were interested in ABC and found Fry particularly appealing. “He likes to have a book on the go, and he’s especially fond of Tom Wolfe and Günter Grass,” wrote one NME journalist in 1982.

“His interests are corrupting the mundane path of fashion, putting pride into style and enriching entertainment. He’s obviously fascinated by the possibilities that being in a group presents; along with Bono, he’s the most enthusiastic and impassioned interviewee I’ve spoken to.”

“Corrupting the mundane path of fashion” may have been referring to the band’s suits – and, in particular, Fry’s gold-lamé number, a brazen homage to Elvis Presley’s Las Vegas glamour.

The polar opposite of the safety pins and torn jeans worn by the punk set, sported by a kid from the industrial wastelands of the north, it was every bit as bold.

Equally bold had been the band’s original choice of outfit – full pro-cycling gear, a look that was copied a decade later by Leeds dance-rockers Age Of Chance.

However, it’s the gold suit that remains ABC’s most iconic uniform, to the extent that Fry still performs in it today.

“I was burgled while in France a few months ago,” he told The Mirror in 2001. “Immediately, I thought, ‘I bet they’ve nicked my gold suit.’ I was so relieved when I realised they hadn’t. It was only then that I realised how much I value it. It has a spiritual value – it’s my talisman, my suit of armour. But you’ve also got to have bloody balls to wear it!”

While Poison Arrow had been a huge hit, the band enjoyed even greater success with the follow-up single, The Look Of Love.

Matching its predecessor’s UK chart position (number four), it also soared to number one on the US Billboard dance chart, as well as hitting the top spot in Canada and France.

Horn and his team pioneered scratching and sampling with a US Dance Mix, while Fry developed his Sinatra-meets-007 style further with a lounge-core B-side, The Theme From Mantrap (Mantrap being the espionage-inspired film vehicle for the band).

Less memorable was The Look Of Love‘s video, an unwatchable mish-mash of vaudeville and Mary Poppins imagery. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Horn chose to be blindfolded for his two-second cameo.

While hindsight has elevated The Lexicon Of Love to classic status – and rightly so – upon its release, the music press was by no means unanimous in its praise.

Rolling Stone was unimpressed by Fry’s “sordid B-movie romantic manoeuvres and smug sexual wordplay”, while Smash Hits felt that “songs like Valentine’s Day get entangled in their own smartness and sound studied”.

By the time the album’s third and final single was released – the UK number-five hit All Of My Heart – Fry and his band had perfected their formula.

The video was cinematic, the band posed as a string quartet on the front cover, Dudley fused the entire album into a three-minute orchestral overture for the B-side and the group took the show on the road – string section and all – for a world tour. But was this formula contrived? “Well, it is and it isn’t,” Fry said at the time of Poison Arrow’s release.

“It’s not like going up to a vending machine and saying, ‘I’ll have a bit of Billy Fury, a bit of Elvis ‘58 and some Stranded-era Roxy Music.’ It’s just utilising ideas that come from yourself and operating with them. I like the idea of being malleable. It’s not treating yourself as a product, it’s just pushing yourself to a limit and finding out how far you can go.”

Sadly, the Lexicon world tour marked the start of the end for the classic line-up. Following a gig in Japan, drummer David Palmer jumped ship to join Japanese electro band Yellow Magic Orchestra, prompting Fry to flush his gold-lamé suit down the toilet.

Singleton was next to go, after his sax was virtually eradicated for Lexicon’s 1983 follow-up, the back-to-basics Beauty Stab. And with Horn never producing another record for the band, the luxurious production that had made Lexicon such a joy was all but abandoned until the group’s fourth album, 1987’s Alphabet City.

All of which makes Lexicon even more special. The story of a group who went from pavement to penthouse, it was, as Horn puts it, “the soundtrack to their lives”. Many of us could say the same.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!