The Lowdown – Depeche Mode

By Classic Pop | February 25, 2015

For more than three decades, Depeche Mode have been quietly conquering the world. Here, we discover how the band came together, before taking a look at their best bits.

Since forming in 1980, Depeche Mode have amassed a staggering 100 million record sales and, in terms of success and longevity, are right up there with U2 and The Rolling Stones. But how did this bunch of Basildon boys end up becoming one of the biggest bands in the world? It boiled down to a combination of things: being in the right place at the right time, boasting a sound – electronic, industrial pop – that was unlike anything we’d heard before, and, above all, having an arsenal of great tunes.

However, even with all those things in their favour, it almost went pear-shaped. In 1981, Depeche Mode looked like they were going to disappear as quickly as they’d surfaced. After a successful first album, Speak & Spell, keyboard player and songwriter Vince Clarke decided to leave. The band weren’t beaten, though, Alan Wilder replacing Clarke and Martin Gore taking over writing duties.

The band gradually moved away from their pop roots and started experimenting with industrial beats and more-meaningful lyrics. Sex, lust, ecology, war and, er, flies on windscreens would all feature in the band’s songs, earning them an increasingly fervent fanbase (especially in the US).

As the Nineties arrived, so the band matured their sound further, culminating in arguably their two greatest albums: 1990’s Violator was a synth peak, 1993’s Songs Of Faith And Devotion a rock reaction to it. On the downside, Dave Gahan found himself battling with heroin and even died at one point – as you do. Then, in 1995, Wilder quit, taking a small slice of the band’s atmosphere with him. Despite these setbacks, Depeche Mode have gone on to produce several more albums and are still prone to flashes of brilliance.

The must-have albums

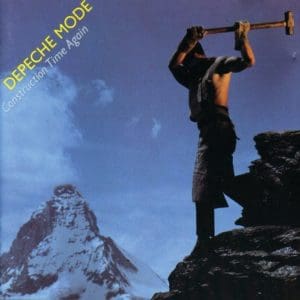

Construction Time Again, MUTE (1983)

The one where the band employed new sounds and thoughtful lyrics

Construction Time Again… and indeed it was. New instruments, including the first samplers, meant new, industrial sounds and beats (best heard on the track Pipeline) alongside the band’s familiar synths.

The writing got darker, more eco-friendly and more poignant with the Martin Gore tracks Shame and Told You So and Alan Wilder’s Two Minute Warning and The Landscape Is Changing. But while these made you think – yes, the world and people were pretty shit back then, too – what got you to the lecture in the first place was Everything Counts.

This was a track that not only had a lot to say – corporate greed isn’t a nice thing – but said it in such a way that you’d still be singing along with it 30 years later. Indeed, the track has since become the closing ceremony of many a Depeche Mode live performance.

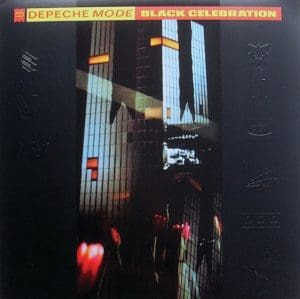

Black Celebration, MUTE (1986)

The one where Depeche Mode went all doomy and gloomy on us

The clue was in the title – Black Celebration saw the band in a dark mood. The title track took your hand and led you superbly into the quagmire, before Fly On The Windscreen – Final saw Gahan spitting out such cheerful phrases as “death is everywhere” and “lambs to the slaughter” over a bleak industrial backdrop. New Dress was even more gloomy, as Gahan played the world-weary traveller, bemoaning murders and bomb blasts before dryly observing that, “Princess Di is wearing a new dress.”

Elsewhere, the jauntier But Not Tonight sounded like Vince Clarke had snuck back into the recording studio.

And standout track Stripped boasted a crescendo that still makes the hairs on my arm stand to attention 26 years later. Surely, a set of songs to confirm Gore as one of the UK’s leading songwriters. It couldn’t get better than this, could it? Oh, yes it could.

Violator, MUTE, 1990

The one you should take with you if you end up on a desert island

Violator was Depeche Mode at the peak of their powers, a collection of supremely produced synth tracks that spawned four cracking singles. The album opened with World In My Eyes, Gahan seducing the listener with lines like, “Let my body do the talking.”

Fan favourite Personal Jesus took its inspiration from Priscilla Presley’s book Elvis And Me, while Waiting For The Night was arguably the band’s finest lower-tempo moment. Enjoy The Silence was a dancefloor filler during the spring of 1990 (and has even been covered by Susan Boyle). Policy Of Truth offered another of those spectacular climaxes the band do so well, beforeClean’s searing strings closed proceedings.

It was no wonder the band’s next step was to bury their synths, grow their hair and buy some guitars – after Violator, they could never reach those electronic heights again.

Songs of Faith and Devotions, MUTE (1993)

The one where the band grew long hair and said, “Let’s rock!”

Another apt title – with his long hair and beard, Gahan must’ve seemed like Jesus to his adoring fans on the band’s subsequent tour. The adulation didn’t sit well with the (by then heroin-addicted) singer, however, who attempted suicide in 1995. If this had been his last album, what a way to bow out.

The band ditched the synths and replaced them with rock theatrics (and a bit of gospel and country thrown in for good measure), Wilder playing drums and Gore picking up a guitar. The truth is, though, the quality of Depeche Mode’s songs is such that they could be re-imagined in any genre.

Walking In My Shoes, Mercy In You, Higher Love and I Feel You were all standouts, but if I could “bagsie” one Depeche Mode song for myself, it would be In Your Room. Yes, it’s mine now and you can’t listen to it without my permission.

The must-watch videos

People Are People

Director: Clive Richardson, 1984

</span<

People Are People and Master And Servant were the singles that finally ingratiated Depeche Mode with European audiences, so the band’s record company were keen to capitalise with suitably captivating videos.

The latter’s video accompanied the song’s none-too-subtle S&M lyrics with images of people painting park benches (yes, really), but more memorable was the People Are People promo, which set out its anti-war message from the off and stuck with it.

Filmed on what looked like a battleship, it saw the band running amok, smacking pieces of metal with large hammers to create their industrial din. And, just in case we didn’t get the message, this was interspersed with footage of various wars and armies marching. The video finished with some shots of the record being pressed, presumably to lighten the load – after all that, we certainly needed it.

101

Director: DA Pennebaker, 1989

</span<

DA Pennebaker’s documentary wasn’t for the faint-hearted, following Depeche Mode on their gruelling 101-date Music For The Masses tour of the US. If the film taught us anything, it was that the band were huge in the States at this point in their career.

Nowhere was this better highlighted than during the climactic concert at the Pasadena Rose Bowl, where 60,000 fans treated the band like rock gods (charmingly, the band looked genuinely taken aback by the reception). The sound quality was crystal-clear throughout, while the song choices were perfect for the occasion. But most engrossing of all was witnessing Dave Gahan in full flow.

Watching him feed off the crowd’s adulation, you couldn’t help wondering how he’d ever match that euphoria. Perhaps the answer lies in the heroin addiction that blighted his life in subsequent years.

Enjoy The Silence

Director: Anton Corbijn, 1990

</span<

“OK, Dave, you dress as a king, take this deckchair and wander around some hills,” is possibly what director Anton Corbijn said at the start of this video shoot. “And I want you in one of those beards without a moustache.” Since Corbijn had already been bossing U2 around for some years, who were Depeche Mode to argue? Gahan obeyed, the rest of the band chipped in with cameo appearances in black and white, and the result was one of the band’s more-memorable videos.

To be fair, Corbijn clearly knew how to make something banal look cool, as proven by the video’s symmetry, locations, colour balance and distant shots of silhouetted landscapes. Then there were the “subliminal” flashes of the Violator cover – the album from which this track came.

“Buy me!” they screamed. The fans took note and the band shifted eight million copies, making it the band’s biggest-selling album.

It’s No Good

Director: Anton Corbijn, 1997

</span<

With the worst of their troubles seemingly behind them, Depeche Mode enjoyed a return to form with the single It’s No Good. The video was no slouch, either. Starting in a bar, complete with dancing girls, glitzy jackets and even a plot (of sorts), it saw Gahan step up to the plate with some tongue-in-cheek acting, before the whole band was whisked away through the streets of New York with their entourage in tow.

This could’ve been construed as Gahan parodying the person he’d become during his darker days – the arrogant pop star getting his own way. Or it may have simply been a celebration that the band were returning to better days, their singer having returned following a stint in rehab.

At the end of the video, they emerged from Hotel Ultra – Ultra being the name of the album from whence this single came. More not-so-subliminal advertising?

</span<