Classic Album: Japan – Gentlemen Take Polaroids

By Anthony Reynolds | March 2, 2015

The fourth album by Japan, Gentlemen Take Polaroids, was their most assured statement to date. However, there were murmurings of discontent within the group behind the scenes during its recording sessions.

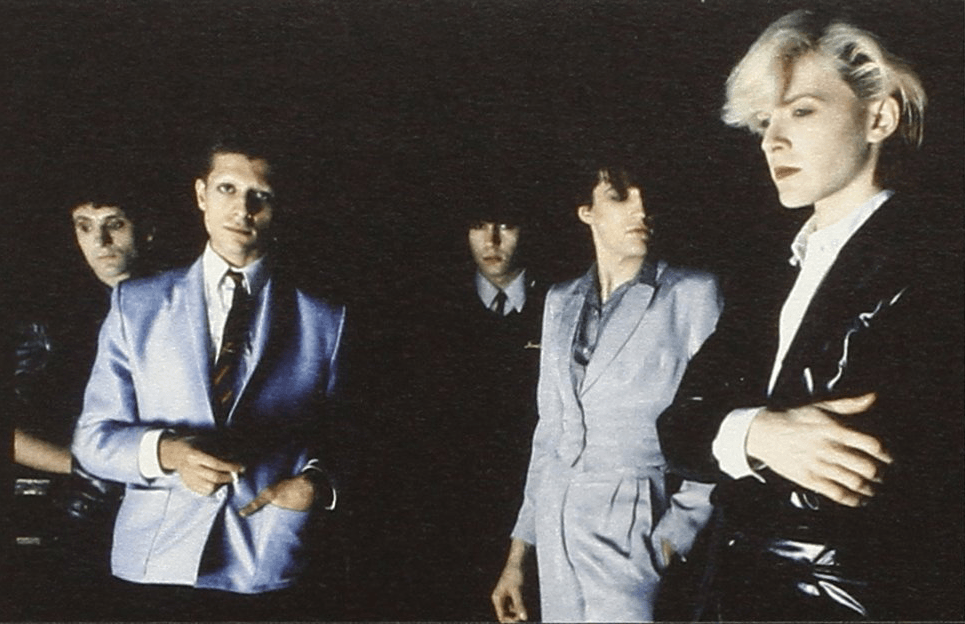

At the time of Gentlemen Take Polaroids’ release in November 1980, Japan were widely considered to be a joke. “Japan’s current sound is one long, diffuse outtake from Roxy Music’s Flesh And Blood,” reckoned the NME. It was a verdict shared by all the major weeklies.

The group had always worn their influences on their sleeves and were the epitome of a group who’d grown up in public. Their first two albums sounded like the aural equivalent of adolescent photo-booth strips: naïve, gawky and fuelled by misplaced hormones.

However, following the leap of 1979’s Quiet Life, Polaroids was an assured statement that reflected both frontman David Sylvian’s new sense of purpose and the rapid evolution of Japan as musicians.

The cover alone was an instant classic, portraying Sylvian as a Helmut Newton-esque artifice that channelled Dirk Bogarde from The Night Porter via the blossoming New Romantic movement.

It was also Japan’s first album release on the Virgin label. Says guitarist Rob Dean, “The transition from Hansa to Virgin wasn’t tense at all. Here was a label that understood more than just commerciality.

On Hansa, we were stablemates with Boney M and Amii Stewart. On Virgin, we were with Magazine, XTC and Simple Minds. We felt confident.”

After signing with Virgin in the summer of 1980, Japan were hurried into AIR Studios, high above London’s Piccadilly Circus. Keyboard player Richard Barbieri recalls, “We’d recorded Quiet Life there and it had been a great experience. We wanted to carry that through to Polaroids.”

“But in this regard, it didn’t work out,” laments Dean. ”Polaroids would turn out to be a rather cold, albeit more sophisticated, album by comparison.”

John Punter, a Roxy Music veteran, had produced Quiet Life and was back for Polaroids. The album took two months to complete. Punter states that, with the exception of My New Career and Taking Islands In Africa, “all the song arrangements were finalised before we started.

“The first thing I’d record was Rich’s sequencer, and the rest of the band would play along to that. Multiple takes would be recorded of each instrument: bass, sax, drums, etc, and the master would be edited from different takes. Additional parts were overdubbed and the vocals were done last.”

After three albums, Sylvian was gaining in confidence, not only as a vocalist and songwriter but also as an arranger and producer. By 1980, he had very definite ideas about how Japan should be presented, visually and sonically, and his new-found focus would alienate him from his bandmates.

- Read more: Japan: Quiet Life – A Retrospective

“There were disputes between Dave and myself,” recalls bassist Mick Karn. “The sax arrangements took days to record, with only Dave hearing anything wrong with each layered take.

“In one instance, [assistant engineer] Colin Fairley sat patiently, recording one word from Methods Of Dance over and over again for three days.”

Sylvian recognises this neurotic obsessiveness in himself, saying, “I tend to be too much of a perfectionist. It caused a lot of problems in the studio.”

The resultant sound, built layer by layer, was dense, polished and panoramic. Aurally, there wasn’t a hair out of place.

However, the same couldn’t be said of its personnel. Musically and even aesthetically, there was little place for Rob Dean in the Japan of the Eighties. His Bolanesque look had fitted in with the previous decade but now he was struggling visually and musically.

“My own creative goals were drifting apart from the rest of the group, which in turn made it increasingly difficult to come up with parts that I was happy with,” he says.

“The band was moving more towards electronic music, with YMO, Eno and Kraftwerk being the strongest influences, and a distorted guitar started to feel more intrusive than complementary.

“Guitar-wise, during this period, the heaviest influence was Robert Fripp’s work, which often sounded decidedly un-guitar-like. As a result, I used a good deal of ebow… but to me, this felt quite limiting. I recall trying in vain to introduce an acoustic guitar part [to Polaroids] at one point.”

“I felt that I was holding Rob back because I had specific ideas for the guitar and I kept imposing them on him,” concedes Sylvian. “It would take hours in the studio because I’d be pushing him a little against what he’d want to do. It came to a peak on Polaroids, as Rob only played on about four tracks.”

- Read more: Making Japan’s Tin Drum

Dean wasn’t explicitly told that his services would be largely surplus to requirements on the album; he just wasn’t contacted for the most part.

“Weeks went by without him at AIR,” remembers bassist Mick Karn. “At every opportunity for guitar, someone would raise the question, ‘Shall we call Rob?’ Only to be told not to. Rob had, in effect, been banned from the sessions.”

It wasn’t uncommon for Sylvian to introduce a cover version into proceedings to alleviate any tension caused by his obsessive nature.

Beyond this, there was always the pub. Japan weren’t, by nature, a sociable band, but the combination of stress and a fondness for their gregarious producer occasionally resulted in the unlikely scenario of the quintet hanging out at an ale-house.

“It was normal to be in a bar somewhere, laughing and joking, and David was no exception,” recalls Dean. “Although I wouldn’t say that he was as relaxed as the rest of us. He was always very aware of his public persona.”

That persona had lost a little of its impact by the early Eighties. Where once the band had attracted hostile attention in public due to their made-up appearance, now, compared to the Steve Stranges and Boy Georges of London, they were hardly noticed. Dean confirms, “Our appearance was sober in comparison to what was around us by that time.”

The same could be said of their on-stage antics. Sylvian, then a chain smoker, would never deign to appear on stage with a glass of water, let alone a cigarette. That’s not to say that Japan didn’t indulge in nefarious substances from time to time – this was the Eighties, after all.

“I think coke entered everyone’s lives in those days,” shrugs Barbieri. “And it wasn’t just the artists, either. But Steve never indulged.”

Dean testifies to the party spirit: “It was an insular group but I wouldn’t call it a particularly sober one. There was a great deal of laughter when we got together, a side that the public rarely, if ever, got to see. Mick and Steve could be very entertaining when they were on form.”

Twelve-hour days were the norm and if the group had more stamina than their producer, they could carry on with a “night shift” engineer, with or without the aid of substances.

Says Karn, “You know the old idea that cocaine goes hand-in-hand with being a musician and working late at night? I don’t think that’s true at all. I think you lose your sense of judgement completely.”

The studio itself was more sociable than most. “With the set-up at AIR, it would’ve been difficult not to interact socially with other musicians,” explains Barbieri. “There would be conversations in the cafeteria and occasionally, this would result in invitations to ‘listening parties’.”

- Read more: David Sylvian albums – the complete guide

Dean expands: “Studio time was never exclusive, other than when vocals were being recorded. I think it helped lighten the intensity when we had visitors. The record company would drop in from time to time, including Mr Branson himself.”

Across the hall from Japan, a new group called Duran Duran were recording their first album. They were huge fans of David Sylvian’s band but there was rivalry, too, with one of the Duranies apparently telling Barbieri, “We’ll be bigger than you because we want it more.”

Japan’s reserved keyboardist was happy to concur with this proclamation but, ultimately, Japan were less taken with Duran than Duran were with Japan.

Karn explains: “[Previous to that meeting at AIR] Rich and I got a cassette from a band who wanted us to produce their album, and it was a band called Duran Duran, who we’d never heard of.

We listened to the tape and there was this track Girls On Film. We thought, ‘God, this is terrible! We don’t want anything to do with that lot.’”

Duran Duran weren’t the only musicians that Japan mixed with. “While we were making Quiet Life, Kate Bush came into our studio, sat on the floor and listened through Despair,” recalls Barbieri.

“Paul McCartney had Studio 2 on almost constant hold. He asked if we needed any guitar on our album. He and Linda were very nice people. We also met Michael Jackson. That was… weird.”

While the band never took McCartney up on his offer, Sylvian was becoming interested in bringing in outside musicians to contribute to his studio sessions. Among them was Hawkwind and Bowie violinist Simon House (Sylvian had attempted to teach himself violin that summer but soon abandoned the instrument).

“It was nice to get outside people working with us,” says the frontman. The irony of this must surely not have been lost on Dean – although, according to Karn, the guitarist “never complained about anything”.

- Read more: Kate Bush Albums: The Complete Guide

Not that Sylvian would’ve heard anyway. “I isolate myself from everyone in the studio,” he said at the time, intensifying the image of himself as the maverick and purist of the group.

Halfway through the Polaroids sessions, the situation was deemed to be so tense that a change of environment was needed. Japan and Punter consequently relocated to Townhouse Studios, across the city in Goldhawk Road.

“I was going through many musical changes,” admits Sylvian today. “I wanted to get away from Quiet Life but still felt attached to it.

That was unusual for me. Things were starting to get strained. I was writing on keyboards instead of guitar, which caused difficulties.” Dean concurs: “The working process for Polaroids was different to previous albums.

“Some of the material was created in the studio rather than in rehearsal, and David was probably more in charge than before. He wanted to move away from the Roxy Music influence but I don’t think he succeeded. It may be that Polaroids was created a year too soon.”

Japan were left to their own devices in the studio, with neither record company nor manager dictating any concession to commerciality, and Sylvian’s vision would struggle to lend itself to the constraints of a band set-up for much longer. No one knew it then but Japan would split up within two years of the album’s release.

Gentlemen Take Polaroids was mixed, mastered and packaged as quickly as possible, with Virgin rushing to meet the Christmas market. Released in November 1980, it reached number 45 in the UK albums chart – bettering any of their previous efforts.

While it would spawn no Top 20 singles (perhaps unsurprising, considering that six of the eight tracks were more than five minutes long), it was hugely influential and, more importantly, set Japan up for their one true masterpiece, Tin Drum. It also bagged the band their first Smash Hits cover.

However, Rob Dean would never record with the band again and the first seeds of Sylvian’s solo career had been sown.

“By the time the album was mastered, Dean was no longer a bona fide member of the band,” recalls the band’s manager, Simon Napier-Bell. “His leaving seemed inevitable. He came from North London and all of the others came from South.

But he’d fitted in and even adapted himself to wearing make-up off stage, and all the other things that David required. His leaving was the beginning of the end of the Japan we’d worked so long to break.

“I was a fan of Japan the people. I loved them. They were sharp, funny, intelligent and always good to be with.”

For Sylvian, though, the constraints he’d imposed on the band were ultimately damaging. “I don’t think [Polaroids] is the best thing we did,” he says. “It was a hard album to make. The feeling between members wasn’t too good because I was putting limitations on them. I’m happy with how the album sounds – the thing is that I was growing out of it before we’d finished it.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!