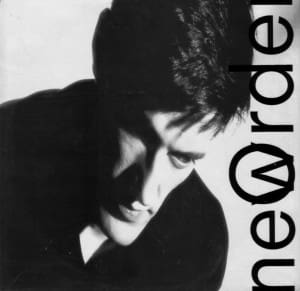

The Lowdown – New Order

By Classic Pop | March 2, 2015

After forming from the ashes of Joy Division, New Order soon established themselves as one of the UK’s most successful Art/Pop groups. Here we take a close look at the highs and lows of this most inventive and influential band.

It was the dawn of the 80s and something had changed. Gone were the dark introspection and ragged funk of the post-punk era. In their place a bright new pop ethos, with flamboyantly clad practitioners famously hogging the charts.

How could New Order, a group emerging from the darkness and real-life tragedy of their former guise, Joy Division, possibly slot into place in this shimmering new age? It was a question that haunted the tentative emergence of the new band.

Several singers were auditioned before Joy Division guitarist Bernard Sumner nervously took over vocal duties, while their sound was fattened by the introduction of Gillian Gilbert’s simplistic synthesiser.

Somehow, New Order wandered into a formula where musical naivety, sheer talent and steely belligerence would echo distinctively through the 80s and 90s. In 1983, four singles and two albums into their existence, they became one of the defining acts of the decade.

With its crisp LinnDrum backbeat, gloriously dipping bassline and lilting, nonsenical lyrics, fifth single Blue Monday hit the airwaves like a juggernaut and went on to become the biggest-selling British 12” single of all time. That it actually lost money with each sale (due to sleeve and production costs) was a perversity that typified the band’s label, Factory Records.

It didn’t matter. Blue Monday was on course to take its place as the perfect melting pot of rock, dance, pop and soul. Reverberating from student bedsits and chromed discos alike, its infectious punchbeat set the tone for a two-decade period that would see New Order stylishly fusing rock, dance, house and disco, sailing commandingly through the Madchester rave years before retreating to a more guitar-driven base in the mid-00s.

Despite their enduring success, New Order’s career has never been plain sailing. Famously fractious – distinctive, low-slung bass player Peter Hook now pursues a career with his parallel band, The Light, following an acrimonious split – they’ve managed to traverse such internal strife, changing trends and mid-period unfashionability.

Despite it all, the distinctive freshness of their music seems curiously undiminished.

The must-have albums

Power, Corruption & Lies 1983

The one where New Order embraced a fresh, electronic sound

If New Order had failed to break from the untidy legacy of Joy Division on their debut album, Movement, with Power, Corruption & Lies they at last managed to turn the corner and focus on a bright new dance-orientated vision borne out of their exposure to electronic and rhythmic beats within New York City’s clubland.

Dismissing the cheap equipment that had marred Movement as a thing of the past, the band invested in a £4,000 Emulator 1 sequencer and, under the guidance of Steve Morris’ technical nous, stumbled through such classics as the thrusting, upbeat Age Of Consent and the gorgeously lilting Your Silent Face.

These twin pillars opened side one and two of the album respectively and, even if the latter contained one of Peter Hook’s most aggressive bass lines, would provide the first glimpse of New Order’s signature sound.

While Power, Corruption & Lies would quickly clasp to the hearts of so many New Order aficionados, the band always disliked the comparitive “thinness” of the sound (echoing their displeasure with the much-loved Unknown Pleasures album back in the days of Joy Division).

Perhaps closer to the point is the sheer speed with which the band had started to evolve. The trick to be learned was balancing the influx of new technology with the best of the old.

- Read more: Power, Corruption & Lies interview

Low-Life 1985

The one where the band broke their own rules

As hinted with Power, Corruption & Lies, there are times when a band needs to take a step back in order to see the way forward. Such was the case with the universally acclaimed Low-Life, the most accessible and consistent album in New Order’s catalogue.

Following the band’s qualms about the thinness of the digital sound on Power, Corruption & Lies, they reverted to analogue and, in Peter Hook’s words, “antiquated equipment”.

Engineered by Michael Johnson at Jam Studios in London, Low-Life emerged as a meatier, dirtier and, ironically, more contemporary-sounding beast, the low-end bass levels in particular managing to reflect the emergent house music of the mid-80s.

The band also broke their own protocol by taking preceding hit single The Perfect Kiss into the studio, before basing the entire sound around the (admittedly remixed) version on the album. Only the instrumental Elegia, which conjured visions of Ian Curtis, broke the prevailing sound.

The album was housed in a Peter Saville sleeve that also broke protocol and, perhaps, signified the band’s careful walk into the mainstream. Their faces were allowed to adorn the front and back, as well as the inner sleeve, albeit shaded by a sheet of opaque paper. For once, heady pretension had been laid to rest. The record looked as it sounded – fresh and contemporary.

Brotherhood 1986

The underrated one that’s well worth returning to

By the time of Brotherhood’s release, New Order had gained the luxury of global familiarity. The album – their fourth – came towards the end of a glorious year for Factory Records and the emergent Manchester scene.

The label had organised the multi-event “Festival Of The Tenth Summer”, which had culminated in a giant gig for the city’s bands at the G-Mex.

After years in the wilderness, a new upbeat vibe seemed to hang in the Manchester air, providing a solid backdrop for the release of Brotherhood, the title of which hinted at a Mancunian comradeship… of sorts.

How odd, therefore, that the album should prove to be a comparatively subdued affair, not helped by a harsh production that, to those schooled on Blue Monday and Sub-Culture, could’ve been regarded as a weakness.

That’s not to say the album wasn’t blessed with sparks of brilliance that would continue the band’s legacy of inspirational uncertainty. Take the extraordinary Bizarre Love Triangle – arguably Bernard Sumner’s finest moment – which featured a diary-esque lyric that seemed startlingly pointed and personal.

New Order had once again managed to find a song that defined the year, if not the era. Despite this, Brotherhood would remain criminally underrated – not least by the band themselves – and deserves a re-evaluation.

Technique 1989

The one where New Order threatened world domination

With the Madchester scene in full flight and the city attracting clubbers and journalists from all four corners, Technique was released with confidence into the raving throng.

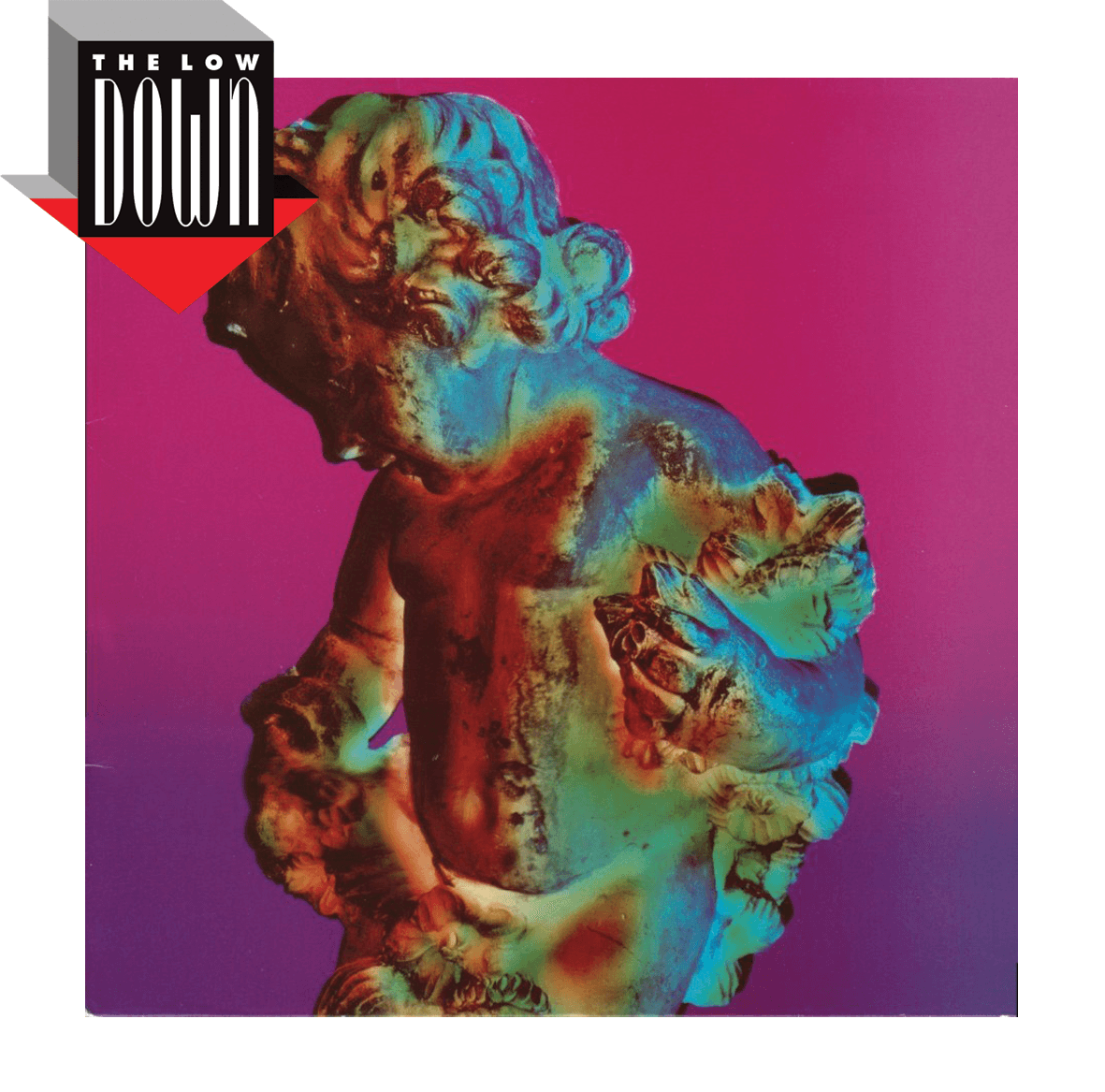

Such confidence, in fact, that a lavish £22,000 ad campaign saw Peter Saville’s cherubic sleeve design adorning billboards across the country.

It must’ve worked as, in January 1989, Technique hit the British album charts at number one. Critics and the public were united in acclaiming it as the most consistently affecting New Order album to date.

It was certainly the most polished, and the production sheen appeared to suit the times. Sumner had even attended singing lessons prior to recording.

All of which only served to fuel the positive vision enjoyed by Factory and New Order, who, at this point, were more than happy to join the “circle of dance” that existed between Manchester and Ibiza.

The album had enjoyed a pre-release hit single, Fine Time, which had alerted the world to the band’s more controlled sound. There, in effect, lay the key to Technique. Gone, it seemed, was that celebrated element of naivety.

Indeed, throughout the entire album, the aforementioned confidence shaded towards an understandable arrogance. It was also the first album where New Order managed to transcend their own legacy, seeping into areas of the mainstream that wouldn’t have previously taken notice.

- Read more: Making Technique

The must-watch videos

Confusion 1983

This video captured them at their most inspiringly arrogant. New Yorkers could only gasp at the audacity of it all. The section that saw the band running down the stairwell was a depiction of a band at their most blasé.

“This one is for all you Funhouse bastards,” Sumner would say onstage that night, casting a sneer at the “dancing hordes” of the disco scene. The video saw a band at the end of their tour and the end of their tether. Revealing and beyond the expectations of the camera crew.

True Faith 1987

At the initial viewing in the Factory office, band and manager burst into laughter, a fact that caused nervous glances throughout the office. Despite this uncertainty, it remains one of their most distinctive visual moments.

Indeed, it’s a commanding sight that draws the viewer into the very heart of the beat. It’s also the band’s most successful video in terms of TV promo shots. However, they’d soon pull back from such visual excess.

World In Motion 1990

Although the video – and, indeed, the concept of the song – would remain controversial among New Order fans, it proved successful in gaining the band a new mainstream appeal. This lighthearted video was used extensively on football shows, effectively bolstering the new and universal “trendification” of the national game. The England team also gained kudos by association. Whether this worked in reverse is still open to question.

New Order Play At Home 1984

It offered a neat insight into the Factory ethos, with Peter Hook interviewing the label’s director, Alan Erasmus, while riding a motorbike and, bizarrely, a fully clothed Gillian Gilbert chatting to a nude Tony Wilson as he sat in his bath.

The playful nature of the film also helped to distil charges of “pretention” that had hovered around Factory and, in particular, their video wing, Ikon. Elsewhere, Martin Hannett prowled while toting a handgun. Hannett was still at war with the label following – in his eyes – their squandering of his money on their Haçienda nightclub.

- Read more: New Order – album by album