The Myth Factory: The Stories Behind Stock Aitken Waterman

By Classic Pop | May 18, 2017

Welcome to The Myth Factory, where we’ll be digging deeper into the stories behind the trio’s production history and debunking some very popular myths. Let’s begin…

1. Pete Waterman was the catalyst for SAW’s earliest success.

When Mike Stock and Matt Aitken started to tout their idea of a female Frankie Goes To Hollywood-inspired dance single around the record companies during the early weeks of 1984, Pete Waterman came to their aid. Having worked with Mike on a novelty record a few years earlier, Waterman seized on this idea and bundled the songwriters into the studio to complete the track after other executives had rejected them.

The Upstroke, billed to Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes, brushed the charts and even secured a spin on John Peel’s late-night Radio One show, but more significantly it was released on Proto Records, and Mike used this connection to exploit some of the songs he had already been working on.

The label released one of them – Mike’s composition Anna Maria Lena – for UK-based Greek-Cypriot singer Andy Paul, representing Cyprus in that year’s Eurovision Song Contest. It finished 15th on 31 points in the competition, but the track (credited to the singer to comply with competition rules at that time but later registered to Stock Aitken Waterman for copyright reasons) had been written the previous year and demoed at Mike’s Abbey Wood home studio in 1983 before being “glammed up” for Eurovision with strings at Hollywood Studios in March.

Barry Evangeli, who ran Proto Records, had signed cult dance act Divine, and asked Mike to work on some new material. “It was an amalgamation of events – Andy Paul and Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes – that led us to working with Divine,” recalls Mike. “Pete had very little to do with this early connection coming together with Barry, but he suddenly realised it was all going on without him. The way we got started with Proto was entirely down to Matt and me, which was odd because we really didn’t normally do that sort of [business] thing.”

Though over time Pete would emerge as the natural frontman for the trio, it’s likely little would have developed without Mike’s drive to make the most of the connections the partnership was exposing. Divine gave the trio their first production hit when You Think You’re A Man made the UK Top 20 in the summer of 1984.

2. Fights in the studio almost erupted during the recording of SAW’s first UK No. 1 hit

It’s a tale that has been trotted out many times over the years, and the image of the late Pete Burns almost coming to blows with Mike and Matt is a delicious one. Sadly, the story that sessions for Dead Or Alive’s You Spin Me Round (Like A Record) turned heated and almost resulted in violence was likely something cooked up as a clever marketing hook during promotion for the track’s torturously slow trek to the top of the charts.

True, tensions did develop between the band and the more experienced hit-makers, but Mike today dismisses the idea that everyone had to be sent home in order to cool their heads. “We always left the studio at 10 o’clock to go down the pub, and on that final day Matt and I had been working on the track, preparing it for the mix,” he remembers, quashing Pete Waterman’s dramatic concoction. “The engineer was due in to do that overnight, so nothing unusual happened.”

Pete Waterman, working on the song with Phil Harding, did battle through some technical problems – a common occurrence at the studio by this time – during that night, but the mix was finally completed ready for Mike and Matt to agree it as normal the following morning.

The story that an unwanted effect had been left on the final mix is yet another fanciful bubble Mike is keen to burst. “There are all these stories that there was an unplanned echo on it, which is just rubbish,” he confirms. “Our plan for that song was to have it spinning around like a record. That was the whole point of it!”

What certainly is true, however, is that later sessions for Dead Or Alive’s subsequent third album, Mad, Bad, And Dangerous To Know, did become more difficult as time went on, leading to the termination of the working relationship between the band and the team that took them to the top of the charts.

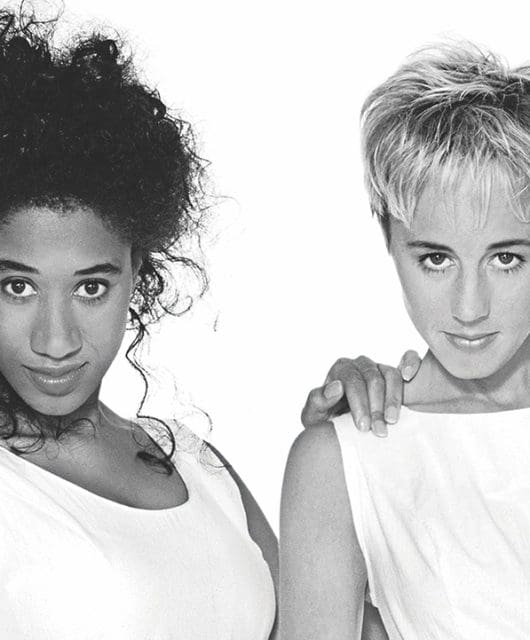

3. Bananarama hated the first cut of Venus

It was Bananarama’s Siobhan Fahey who suggested approaching Stock Aitken Waterman in an attempt to inject some fresh creative energy into Bananarama’s by-then flagging chart fortunes. She had loved You Spin Me Round, and in 1986 the producers still had the maverick credibility she instinctively craved for the group.

Venus, written at the tail-end of the 60s by Shocking Blue guitarist Robbie Van Leeuwen, was a song the trio had routinely performed when they were starting out on London’s club circuit, but Pete’s immediate response was that they should steer clear from such a well-loved song. Still, the band was a big commission for SAW at the time, and agreement was reached to give it a go.

Mike recorded the song with the band on his own in just two hours at Deptford’s The Chocolate Factory studios in south-east London. “They had already done the routine on the vocals but, when I said it was done, they couldn’t believe it as they said it takes them three days to record with [former producers] Jolley& Swain,” he recalls.

The story that Siobhan popped back from the pub, heard a soft, pop/soul-oriented take on the 60s classic, expressed disappointment that it didn’t sound anything like the Dead Or Alive chart-topper and ordered an immediate rethink isn’t based in reality, confirms Mike. “The idea was always to emulate the You Spin Me Round sound.”

4. Artists were always keen to get a SAW credit

Some acts were actually rather coy about the involvement of Mike and Matt on their hits, sometimes leaving the SAW name off the credits. Most significant of these was the debut single from Pepsi & Shirlie, the duo who had supported Wham! on their staggering success during the mid-80s.

Mike helped out on Heartache – a single that would have topped the charts if the vocalists’ former boss hadn’t released his own duet with Aretha Franklin at the same time. “I played and programmed the bass on that single,” recalls Mike. “Pete Hammond was taking control of the mix and he wasn’t happy with it, so I got involved one evening and I did also go through the vocals with Pepsi & Shirlie.”

Mike had performed similar duties on Phil Fearon’s 1986 Top 10 hit I Can Prove It and would later fix the bass on Sinitta’s Love On A Mountain Top, which was a hit for her in 1989.

5. Everything SAW touched turned to gold

Despite their reputation as almost-unparalleled British hit-makers, SAW had their fair share of flops with a surprising number of singles stalling at the frustrating UK chart position of 41, thereby missing out on crucial radio airplay and an essential Top Of The Pops appearance.

Mike blames the major record labels for having such a stranglehold; “It was very close to being impossible if you were independent and unconnected commercially to the mainstream business interests,” he says. Hazell Dean, for example, ended up with a string of SAW singles that just missed the Top 40, while veteran artists like Edwin Starr, The Three Degrees and Georgie Fame failed to enjoy anticipated career revivals with the team.

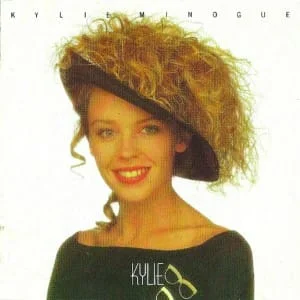

6. Kylie’s first album was certain to be a sure-fire smash!

In the end, 1988’s Kylie album would sell more than five million copies – but cash flow was a serious problem. Naturally, the LP had to be pressed before a single copy could be sold, and the sheer numbers involved gave Pete Waterman some sleepless nights.

“My bottle went completely and I was convinced I was out of business,” he says. “I’d spent all the money on TV advertising, and now here was a small country’s worth of records just lying around.” The album’s sales exploded as the year progressed, especially in the run-up to Christmas, and its eventual success redefined the definition of an independent release.

The next year, Ten Good Reasons by Kylie’s Neighbours cast-mate and then-boyfriend Jason Donovan would sell nearly two million, but finances were still often tight at PWL, with money pressures eventually forcing Pete to enter into a partnership with a major label.

7. SAW worked with Roland Rat

The children’s fave had scored a couple of small chart hits in 1984, and by the end of 1985 the rodent was newly-contracted to the BBC. An album, later to be titled Living Legend, was commissioned by BBC Records, and Pete grabbed the opportunity to innovate.

“That rat was my alter-ego,” he said in 2015. “I could do anything I wanted with it. No one cared about it and I was being paid to experiment. If you listen to that Roland Rat release, you’re hearing an early Mel and Kim record.”

The tongue-in-cheek notes claim the LP was recorded in the Bahamas, mixed in Montserrat and mastered in Brentford. Whatever the truth of the matter, SAW were credited on four of the 12 songs; however, Mike today says he didn’t actually work on any of the tracks, and it’s likely that this was one of those rare examples where SAW were billed solely for marketing purposes.

Later in the decade, a SAW credit was also added to remixes of Kool & the Gang’s Celebration and Sabrina’s Like A Yo-Yo.

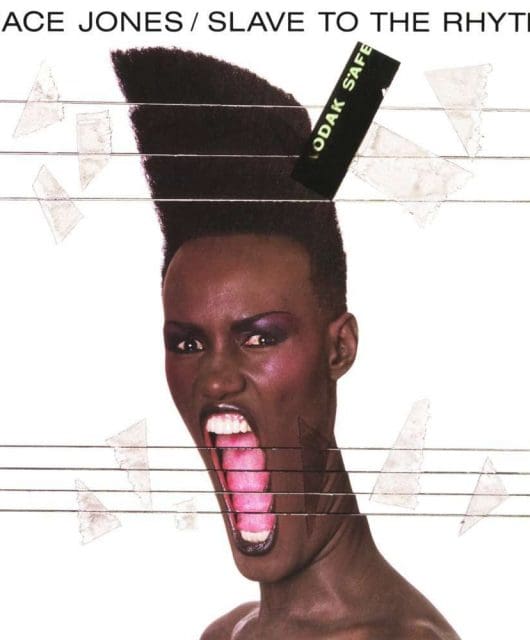

8. Donna Summer never came back to the hit factory

By the late 80s, Donna Summer’s career had stalled. The singer’s frequent record-label changes signalled a serious creative stutter, while an alleged comment about AIDS had served to alienate a large part of her core fanbase.

Noting Rick Astley’s spectacular Stateside success, she turned to SAW to craft the 10-track pop-dance masterpiece Another Place And Time. The strategy worked… spectacularly.

The first single, This Time I Know It’s For Real, took her back to the Top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic in early 1989 and, while the reviews were mixed, many claimed this was SAW’s finest hour.

Sadly, it didn’t signal a long-term partnership. Donna’s next full set took until 1991 to appear; recorded not with SAW but with a range of different producers and rather aptly named Mistaken Identity, it flopped badly.

It has long been rumoured that Lonnie Gordon’s 1990 smash Happenin’ All Over Again was written with Donna in mind, but Mike says this is not true and the track was prepared specifically for Gordon – also in desperate need of a hit.

Donna’s decision not to return to The Vineyard, SAW’s studio in south-east London, baffled Pete.

“I don’t know what went wrong… it’s weird, ‘cause I’ve never seen her say anything bad about us in interviews,” he told pop weekly Record Mirror almost a year after Another Place And Time had been released.

In fact, Donna did return – but too late. In 1993, long after Matt had left the team, Mike and Pete had a blazing row about a proposed new project with Dead Or Alive that was to mark the fiery finale of their joint venture.

A lengthy legal dispute was to sour relations further between all three men and, today, Mike’s greatest regret from the whole period is that when Donna Summer did finally approach Pete again about setting up a new deal, he had not long left The Vineyard and the opportunity was lost.

9. Pete wrote a lot of the songs

The working partnership between Mike, Matt and Pete was a fateful combination, with each bringing a particular skillset to the mix.

Mike and Matt were the songwriters and, while Pete certainly steered some of the musical direction, his role was business-facing, promoting the SAW brand and bringing new projects to The Vineyard.

His position as principal spokesman has led many to assume his involvement in the creation of those hit songs was bigger than it was.

This misconception remains a source of tension to this day, and Mike says Pete’s engagement with their work was actually diluted over time with commitments like The Hitman & Her TV show dragging him elsewhere.

Later interviews and Pete’s 2000 autobiography I Wish I Was Me exacerbated the issue, but relations have since thawed between the three men.

In 2015, they worked together again in the studio for a remix of Kylie’s festive single Every Day’s Like Christmas and with the long-overdue critical re-evaluation of the SAW back catalogue underway, it may be that a better understanding of the magic formula that created the soundtrack for a pop generation is finally – and deservedly – developing.