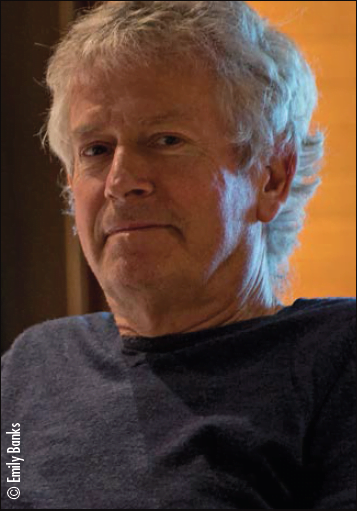

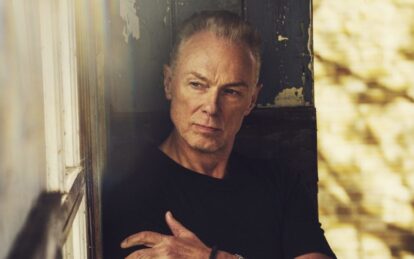

Douglas McPherson speaks to Tony Banks about his experience in Genesis, as well as his new classical direction.

Keyboardist Tony Banks formed Genesis with singer Peter Gabriel and bassist Mike Rutherford while they were at school together. During the 1970s, the band epitomised prog rock, drawing folk and classical influences into complex tracks on albums including Selling England By The Pound. During the 80s – in parallel with Phil Collins’ hugely successful solo career – they forged a more pop-leaning sound and enjoyed a string of hit singles including Turn It On Again, Mama and Invisible Touch, which established the band as one of the world’s biggest stadium acts. Outside of Genesis, Banks has composed film scores, released solo rock albums including The Fugitive, and most recently composed three classical LPs, including his latest, Five.

If it hadn’t been for Genesis, do you think you might have pursued a career as a classical pianist and composer?

No, I think I’d have been a research scientist or something! (chuckles) Genesis happened because of my friendship with Peter Gabriel. We encouraged each other to get into the business in a way that we might not have otherwise. We were children of the 60s and big fans of The Beatles and The Kinks. So the fact that we were able to follow it through was a bit of a dream. I don’t consider myself to be nearly a good enough pianist to be a classical player, but the writing is something I always wanted to do and I was very glad to be able to do that.

Is it true that Peter Gabriel’s theatrical stage costumes surprised even the band?

Only once – the first one, really. We were in Dublin, and halfway through The Musical Box. Pete walks on wearing his wife’s dress and a fox’s head – for no particular reason at all. We were all a bit stunned. We had no idea who it was to begin with! But the next week we were on the front page of Melody Maker, so we thought, ‘Hey!’ and that became part of our thing.

Did you think Genesis would survive the post-punk backlash against prog rock?

It’s a strange thing, because we were out of the country when that happened. We released our least commercial album, Wind & Wuthering, in the middle of that and I think the people who liked us stayed with us as a result of that. Shortly after we had …And Then There Were Three…, which was our biggest album to date at that point. We had a couple of hit singles on it and became more radio friendly. A lot of the other prog rock bands either split up or became more background and were able to carry the progressive flag on a bit.

Did you make a conscious decision to be more commercial in the 80s?

The only conscious decision we ever made was in about 1981, when we did the album Abacab. We thought we’d make it a little bit more concise. We always did long and short songs, we just got better at the short ones. I’m very proud of tracks like Land of Confusion. To me, they say it all in four minutes whereas it used to take us 27 minutes to say anything. The personnel changes made a difference as well. If I was trying to take the music in a more extreme direction I had more of an alliance with Peter Gabriel and Steve Hackett (the guitarist) whereas Phil Collins and Mike Rutherford have a more commercial ear. I always thought that I dragged us back from being an incredibly popular band because I always put those difficult chords in. Even songs like Turn It On Again go through lots of changes.

Did Phil Collins’ solo career have an influence on the band’s direction?

Not on the direction. It had a big influence on our success. Phil became so big, but I think the two careers helped each other. It gave Phil more background to have Genesis as well, to prove what a good drummer he was. From our point of view, it kept us in the headlines. I suppose Invisible Touch benefited from the fact that his voice was familiar. But who can say? It certainly did us no harm!

What’s it like moving from the rock world to the classical world?

There’s quite a lot of hostility – particularly when I did the first LP. There’s a tendency to be dismissive and some people won’t even give it a chance because of where it’s come from. But there’s been a lot of history now of people who’ve come from the rock world and done things. The most famous is Karl Jenkins who’s had so much success in the classical world that they have to take him seriously. When I did my first classical album with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, some people in the orchestra were great, others were not. That’s why I made the last two albums in Prague, because I found the orchestras over there to be more enthusiastic.

Five is out now on BMG. Find out more here.

Read more: The Godfathers of Pop: Peter Cox interview

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.