Picture credit: Paul Husband

How did a scruffy school dropout from Salford write songs that came to define the Madchester era? In this Shaun Ryder interview the Happy Mondays frontman tells Classic Pop about his life as a songwriter… By Jonathan Wright

The late, great Tony Wilson was not a man who believed in understatement. His take on Shaun William George Ryder, lead singer with Happy Mondays, was a case in point.

Here, declared the boss of Factory Records loftily, was a Mancunian wordsmith worthy of comparison to one of Ireland’s greatest poets, WB Yeats.

“I didn’t know who Yeats was,” laughs Ryder today. “I had no idea and then, ‘Oh, he’s a poet and he’s fantastic.’ ‘Oh nice one, Tony, thanks.’ He didn’t compare me to a drug-addled twat living in a box under the fucking motorway, so I took the compliment.”

As a new collection of Ryder’s lyrics, Wrote For Luck, makes clear, Wilson wasn’t being entirely fanciful.

Focusing on Ryder’s lyrics from the late 1980s to the 1990s – from the Mondays’ debut, Squirrel And G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out) through peak Madchester and the messy comedown, and onwards to his work with Black Grape – it’s a reminder that Ryder is one of our foremost songwriters, a storyteller whose tall tales, which so often turn out to be based on hedonistic experience, have an immediacy that makes them jump off the page.

None too shabby for a man who, by his own estimation, became the Mondays’ frontman by default. “I wanted to be a drummer,” says Ryder. “I’d got some drums and I couldn’t fucking play ’em and then, when we got everyone together, I was the singer. We all were having a go at writing and they were shit. And I was the best out of the bunch, so there we go.”

Shaun Ryder interview: Made In Salford

In truth, the story of how Shaun Ryder came to tell his stories to the world, is a little more convoluted than this and involves going back to his childhood.

Born in Little Hulton, Salford, in 1962, the young Ryder was a kid who delighted in wordplay. Ordering a “chippy dinner” at the chip shop, he’d turn the price board into a song. “I was the class clown, so I used to make people laugh by making up rhymes,” he remembers.

If only school had been so easy. “I’m dyslexic,” says Ryder. “I had real trouble at school. I went to a Catholic school in the 60s where every time you picked your pen up with your left hand, you was fucking hit by a stick on the knuckles. So I’m not naturally right-handed, I’m ambidextrous. I play football with my left leg, and play pool and so on, and so I ended up writing in circles. And I can’t spell for shit.”

‘I wanted to be a drummer. I’d got some drums and I couldn’t f**king play ’em and then, when we got everyone together,

I was the singer.’

At least at primary school, his mum worked in the infants as “what you’d call a teaching assistant now” and “kept an eye on me early doors”.

At secondary school in the 1970s, he wasn’t so lucky.

“It took me a long time to understand simple things so you was in the crowd control class, so I pretty much dropped out of school and never went past the age of 13,” he says. “The only way I learnt my alphabet – when I was 26 years old – was my girlfriend at the time taught it to me through singing, and I sung it and learnt it in five minutes.”

To look at that another way, maybe Ryder’s problem wasn’t so much that he wasn’t paying attention, but that other people weren’t paying attention to him. Yet one of the strengths of his writing arguably lies here. With no template to follow beyond the idea of fronting a band, he had to invent himself as a writer.

“It’s like [Mondays guitarist] Mark Day,” says Ryder. “Mark was the only one who could read music out of us lot. I didn’t play a guitar, and I would say to him, ‘Can you do this? Do this.’ And Mark would go, ‘Can’t do that, you just don’t.’ And I’d say. ‘Fucking do it.’ So Mark ended up playing lead and rhythm guitar at the same time, do you know what I mean? He was doing things I thought you should be able to do, but musically on paper you couldn’t do.”

Shaun Ryder interview: Growing Up In Public

This process would culminate in the shimmering Pills ’N’ Thrills And Bellyaches, but other Mondays’ records sound far rougher.

In part, says Ryder, that’s because, thanks to having northern soul DJ Phil Saxe as manager, a man “who grew up with [Hacienda DJ and Factory A&R man] Mike Pickering and [Joy Division manager] Rob Gretton, and knew Tony Wilson”, the Mondays “got on vinyl too early” at a time the band “couldn’t even play our fucking instruments”.

So what did Wilson see in the band? Shortly before Factory went belly up, I interviewed Tony and he quoted with approval George Martin’s story of signing The Beatles.

It wasn’t that the Fab Four were especially fantastic at this point, but there was something about them, the way they carried themselves. Record company executives, said Wilson, too often worry about not hearing the hit singles that a band hasn’t written yet.

Ryder’s memories of Wilson tally with this. For all that the Mondays were, circa the first LP, “drugged-up” and “running around like knobheads”, Wilson saw something in them.

“He was all for us, he really, really was, he was totally behind us,” says Ryder. “I mean, Peter Hook fucking hated us lot. When we first came on the scene, Hooky hated us, cos we was from round his way, we was just fucking ill-mannered scroats.

“We were nice people, but he fucking didn’t like us, he wouldn’t let us anywhere near, but Tony loved us more as a bunch of lads than as a band.”

Shaun Ryder interview: Sorted For E’s & Wizz

The Mondays progressed at an extraordinary rate, not least because Ryder began to look beyond what he thought he should be writing and started sketching out scenes he could see playing in his head.

“[Writing songs] is like writing short stories,” he says. “Not poems, but short comic-strip stories is my job as a songwriter. A lot of the songs I write, to be honest, there’s about three or four different fucking subject matters going in ’em. There’s a bit there about that, a bit about that and something that’s come in me conscience and I’ve made a statement on that, and then what I do is I just find a way to piece them all together to make it look like one flowing continuous story. And that’s it, that’s what I do.”

Part of finding the freedom to do this was down to drugs. More specifically, ecstasy came to Manchester. “I’d been in Amsterdam and, when I was coming back, a pal of mine put some ecstasy in his toothpaste,” says Ryder. “And that’s how the first bit of E, as far as I know, got into Manchester.”

More specifically, in Ryder’s estimation, the early Mondays played rock, disco, funk or whatever, but never truly blended sounds as they did later.

“[Ecstasy] just chilled us out, just to relax and do that,” he says. “That’s my opinion. We was all taking E at that time. It’s like what happened with the Roses. I mean, you look at the Roses’ early stuff and then look at Fools Gold. There’s nothing like Fools Gold in what they were doing. Again, I don’t know, is that the result of an E or is that the result of the changing times? I’m not too sure.”

Shaun Ryder interview: Mad Fer It

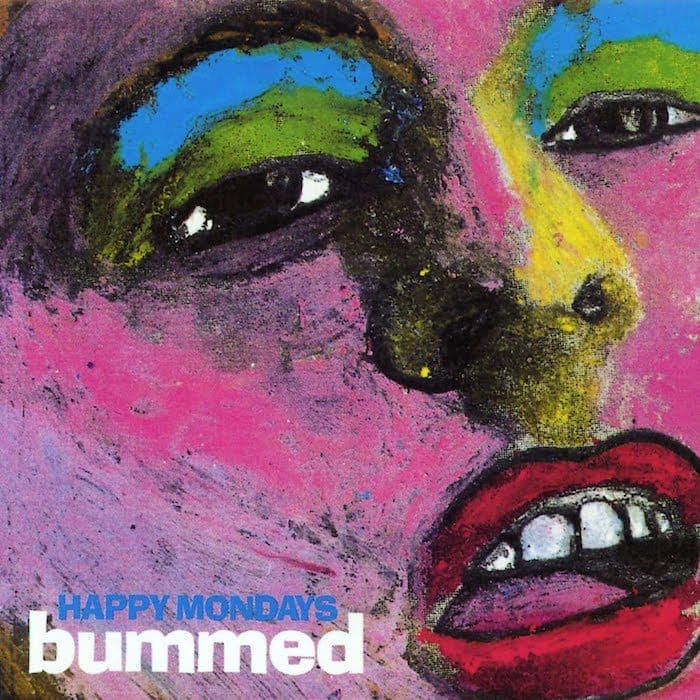

As the Mondays recorded Bummed with Joy Division producer Martin Hannett, Shaun and the band were inventing Madchester, helped along by a friend buying DJ Paul Oakenfold’s record collection, the discs he had been spinning in Ibiza. Even more importantly, with Steve Osborne, Oakenfold would produce Pills ‘N’ Thrills in Los Angeles, an album that brought another shift in the Mondays’ songwriting.

Oakenfold, Ryder says, “would throw beats” over which the band would play. To catch the change in approach, think of Bummed as essentially an indie album. Now think of the way Mark Day’s guitar melodies seem to glide over the bass in Kinky Afro.

Read more: Top 20 Pop Side Projects

Read more: Making The Stone Roses – The Stone Roses

“I’m just sat there and I don’t need anything else except a beat or a bassline,” says Ryder of the recording. “That’s all I need and, if it turns me on, I’ll write to it. On them songs then, I’d pretty much knock one a day out when we was working.”

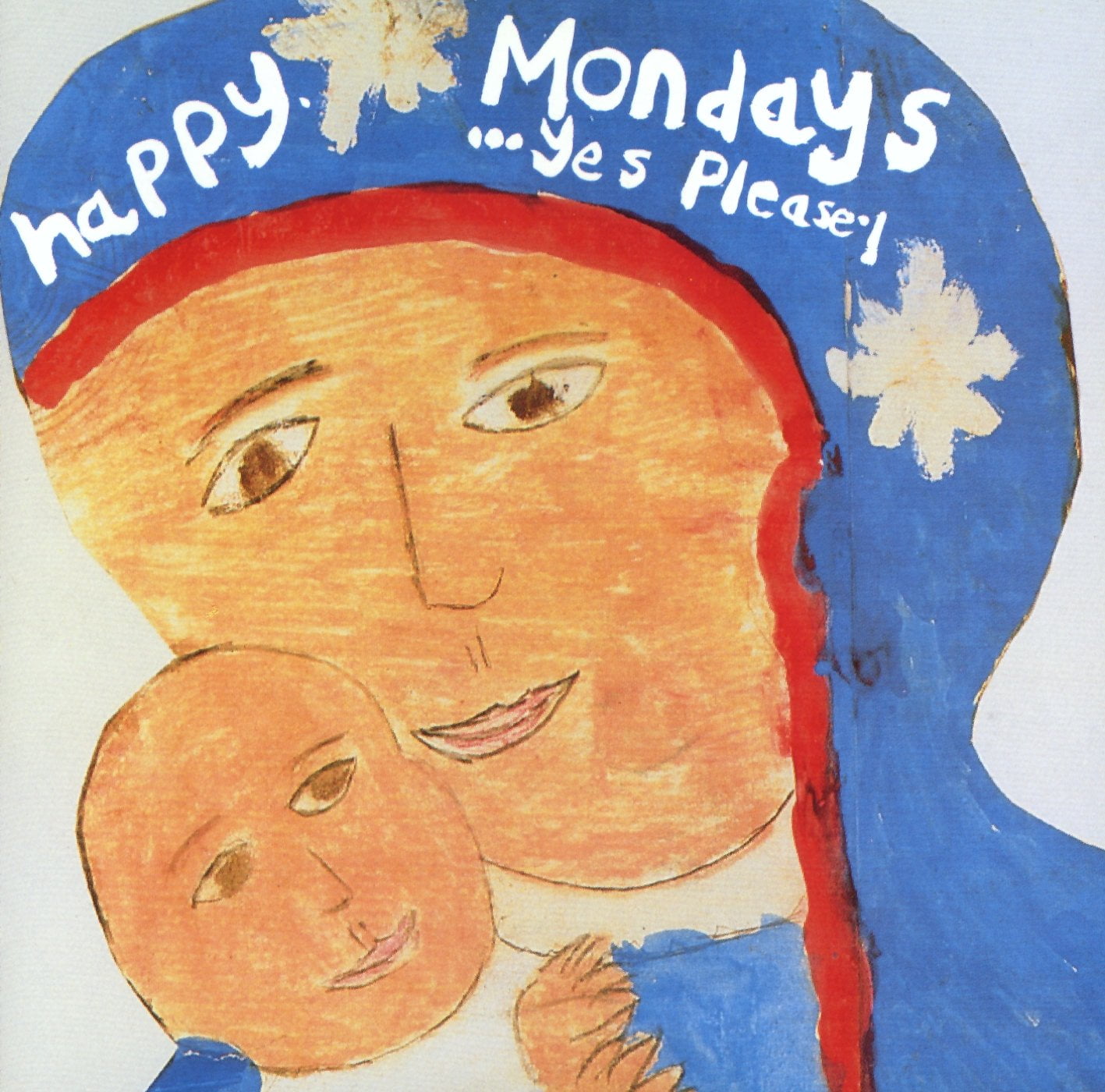

The contrast with the Mondays’ fourth album, …Yes Please! couldn’t have been greater. Recording on Barbados with

“I’ve seen a lot of people who live life on the edge, but I’ve never before seen a group of people who had no idea where the edge is,” Weymouth noted. But the problem, says Ryder, was less the band’s drug intake than the fact that they had chosen the wrong producers.

“They’re genius but it didn’t work for us,” he says. “It didn’t turn me on, so all I would do was get frustrated and angry, and I got off my nut.”

Back in Britain, Ryder entered rehab. As Ryder remembers it – and he’s always especially careful to specify this is his version of events where other band members may have a different view – he and Bez tried to keep the band together but egos got in the way rather than drugs.

Going to Top Of The Pops, he says, “The door would open for me and Bez and then they’d let it go and slam it in the face of the rest of them. And that pissed them off.”

Shaun Ryder interview: The Comeback King

Whatever the truth here, largely withdrawing from the public eye after years when he had been a rent-a-quote presence, Ryder seemed washed up. In fact, he had signed a new deal and was preparing to launch Black Grape. He came back with a No.1 album, the ironically named It’s Great When You’re Straight… Yeah, on which Ryder swapped ideas with rapper Kermit, formerly of Ruthless Rap Assassins.

“The quick version of that is me and Kermit were smack brothers,” says Ryder. “And usually when the drugs stop, you stop being friends cos you’ve got nowt in common. Well, me and him have got a lot in common and it’s a great relationship. So for me and him, bouncing off each other, that’s what we do.”

Recording Black Grape’s Pop Voodoo (2017), he says, the duo “sat there like Alas Smith And Jones”, back in the groove.

So after all these years, does Ryder, sober these days, still feel fired up to write? “Oh God, more than ever, more than ever, because I’m 56 years old and I’m happy with me now, me, the person I am,” he says. “I’m happy with that. And I’ve got a missus who fucking loves me, and me kids, so I’ve got a solid base and so I’m dead, dead happy. I love doing everything I do.”

Watch Shaun Ryder’s best Gogglebox moments here:

Listen to the Happy Mondays on Spotify

Read more: Making New Order’s Technique

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.