Introducing the pioneering devices that shaped 80s pop. Members of The Human League and Landscape reveal the true story behind the electro revolution, from blowing up drum machines to prank-calling The White House…

The LM-1, DMX, TR-808… not an extract from a trainspotter’s logbook but, in fact, a list of some of the most important players in pop history. This is the tech – the synthesisers, sequencers, samplers and drum machines – that facilitated the 80s’ most memorable pop masterstrokes, including When Doves Cry, Don’t You Want Me and the unstoppable Blue Monday. We showcase the classic devices that shaped the decade’s defining sounds.

A New Dawn

When synthesisers first arrived in the late 60s and early 70s, they were colossal pieces of kit – huge rack-mounted modules shrouded in metal and wood, teeming with wires, valves and buttons. Typically custom-built, at huge expense, they more closely resembled the Enigma code-breakers’ command centre than anything that might be confused for a musical instrument. Getting a sound out of them was another matter entirely. Just creating a simple sequence in the pre-digital days (something we can now all do on a smartphone) was an operation of military precision.

“For my generation of cash-strapped kids,” explains ex-Human Leaguer Jo Callis, “the guitar was the most accessible instrument for those of us with delusions of grandeur… When early synthesisers began to appear, they were mysterious, complex looking machines and prohibitively expensive. But we were fascinated by them, they were new and futuristic.”

The 80s made the technology considerably cheaper, more portable and hence more accessible, putting these exotic sounds into the hands of ordinary people. You no longer needed a king’s ransom, a cavernous outbuilding and a computer science degree in order to purchase, install and then actually figure out how to play them. “You suddenly had these new, affordable synths which you could get great sounds out of fairly quickly,” says his bandmate Ian Burden, “and that’s how The Human League began.”

That said, synths were still a sizeable investment. As John L Walters, of early pioneers Landscape tells us: “My Lyricon was enormously expensive compared to a saxophone or flute, even though I got a hefty discount.”

Yet, feasibly, you could beg, steal or borrow enough cash to hop on the bus, pick up your new toy, open the box then instantly start creating.

Jo Callis did exactly that, at first borrowing gear from his local music shop, including an early drum machine. “In fact, I’m sure the drum beats on Seconds were originally ‘copied’ from that little box. I eventually blew the beggar up using a wrong power unit. The lads at Sound Control didn’t seem too perturbed about it – they were mostly rockers and metalheads.”

A young guitarist called Dave Stewart convinced his bank manager to lend him £5,000. What he didn’t squander on drugs he put to more creative use, purchasing a synthesiser, attracted by the possibilities of a new approach. The result? Sweet Dreams.

The technology was novel, but the innovators used its limitations to their advantage – even clunky features formed the basis of now iconic sounds. The real beauty was what it enabled the artists to do: push boundaries and explore new ways of songwriting based on grooves and loops – ultimately filling the dancefloors the world over. “We were really pushing at the creative envelope of what these wonderful little machines could do,” says Callis.

“It changed everything,” continues Walters. “It turned us from a jazz-funk-fusion band into ‘synth-pop chart-toppers’.”

New Order – Blue Monday

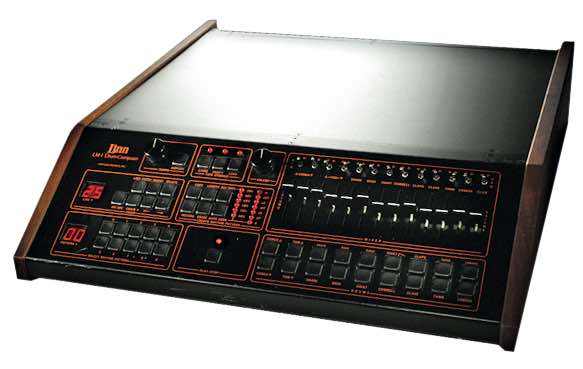

Oberheim DMX Drum Machine

“She makes my heart beat the same way, as at the start of Blue Monday, always the last song that they play at the indie disco.” So sang the ever-observational Neil Hannon, about the biggest-selling 12″ of all time. Just from the opening machine-gun attack of a single kick drum sample, any dancefloor – anywhere in the world – will fill up instantly.

Possessing one of the most iconic and instantly recognisable intros in recorded music, Blue Monday began on a small, portable drum machine introduced in 1981: the Oberheim DMX, programmed by New Order’s drummer Stephen Morris. At this point, sequenced electronic music was such a nascent technology that the DMX was synced up to an improvised, homemade sequencer device, built by guitarist and singer Bernard Sumner.

But the legendary sound that millions know and love today was a partial fluke. Having meticulously plotted out the intended sequence, which had to be inputted using archaic binary code, keyboardist Gillian Gilbert accidentally missed a note out of the sequence. The resulting part was slightly out of sync, but human error helped spawn a classic.

The band also employed an early sampler, the Emulator 1, to build the track’s various sonic elements. Like their contemporaries, they were keen to see how they could manipulate the technology towards new ends. As Gilbert once told The Guardian, Sumner and Morris mastered this new-fangled device “by spending hours recording farts.”

Pushing the boundaries in the studio was one thing, but performing their biggest hit live would often prove a nightmare – as anyone who watched their limp Top Of The Pops performance would attest.

Heavily inspired by the LinnDrum that preceded it, the DMX’s slighter cheaper price made the possibility of professional production even more attainable. Hence the DMX became a bedrock of the US’s burgeoning hip-hop scene, one rapper even took his name from it. Elsewhere, the DMX cropped up on hits by The Police, Prince and the Thompson Twins.

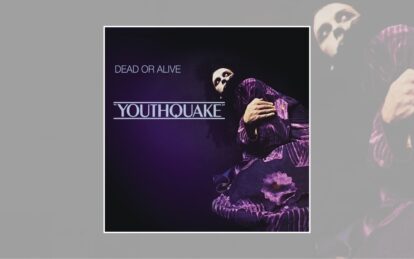

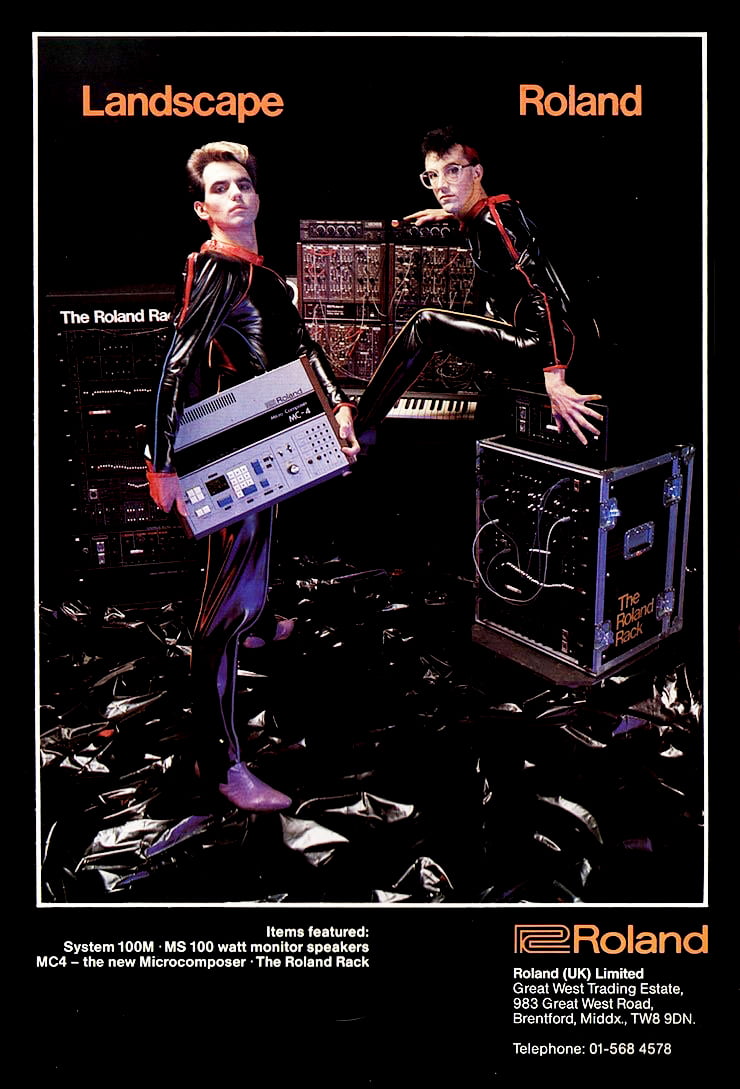

Landscape – Einstein a Go-Go

Lyricon (wind synthesiser) / Roland MC8

If anyone embraced the electro revolution, it was the criminally overlooked Landscape. They even demonstrated these new-fangled synths on the BBC’s flagship technology show, Tomorrow’s World. John L Walters tells us more: “There was a glorious day in the summer of 1978 when I walked into a music tech show in Russell Square and encountered the two instruments that would change my life: the Roland MC8 Microcomposer, and the Lyricon wind synthesiser. Amazing. I talked of nothing else for days!

“We recorded the catchy synth part of Einstein using my Lyricon Wind Synthesiser Driver” – essentially, an electronic clarinet/sax used to create synthesised sounds. “We used a mic to catch the breath and key noises, so that listeners would subconsciously know that someone was actually blowing this part, rather than just sequencing it.”

“Recording the phone calls required dismantling a phone receiver; those are genuine prank calls that I made to the White House!”

The Human League – Don’t You Want Me

Roland System 700

“We were always very concerned to program our own sounds,” says Ian Burden. “The whole Dare album used maybe only five or six synthesisers on the whole thing. For me, breaking the rules was always a part of it. It’s like, what can you do to make your instrument sound different to what everyone else is doing? How much can you draw out, beyond what it’s designed to do, which takes me to Pink Floyd – it was astonishing what they could pull out in terms of the range of sounds.

What if you plugged your foot pedal the wrong way round? What happens if you mess with the microphones and feed a mic through some other device? By way of that experimentation, you can come up with this incredible range of sounds.”

I persuaded Martin to let me see if I could trigger the programmed sound by plugging a guitar in, and give it a human ‘funky’ feel. So out came my Fender Telecaster, which, as luck would have it, I just happened to have at hand! After a bit of tinkering and knob fiddling, he had something happening. I wasn’t actually ‘playing’ anything, but merely creating a shuffling rhythm to the part with my ‘strumming’ hand. But I think I can say that it was the first use of a guitar on a Human League record!”

Rick Astley – Never Gonna Give You Up

Linn LM-1 Drum Computer

We’ve chosen the Rick-rolling classic, but any of the Stock Aitken Waterman stable would illustrate the point, from You Spin Me Round (Like A Record) to I Should Be So Lucky. Practically every SAW hit is announced with a bubbling drum fill that detonates a chugging rhythm, complete with syncopated bassline – a ‘locomotion’, if you will.

So how did SAW achieve that trademark sound? A clue is that the drums are invariably credited to ‘A. Linn’. In fact, this elusive character is just a box the size of a cereal packet: the Linn LM-1 Drum Computer. As much as any other device, the LM-1 (and its later incarnations) came to define electropop. As Ian Burden tells us: “The arrival of the Linn LM-1 was a game changer.” It was a key component of The Human League’s breakthrough album, Dare.

One of its greatest ambassadors was Prince, who used the LM-1 extensively in his 80s imperial phase, notably on When Doves Cry (which to this day still leaves fans baffled over how he achieved that beat). The master of innovation took his drum machine one step further, rooting it through a guitar effects pedal.

Only 525 of the original Linn LM-1 were ever built, yet its impact has been truly colossal. Literally hundreds of millions of record sales owe a debt to that small box. Inventor Roger Linn is little known beyond certain circles, but clearly the man should be canonised.

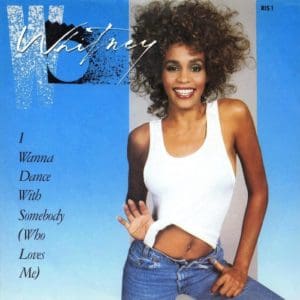

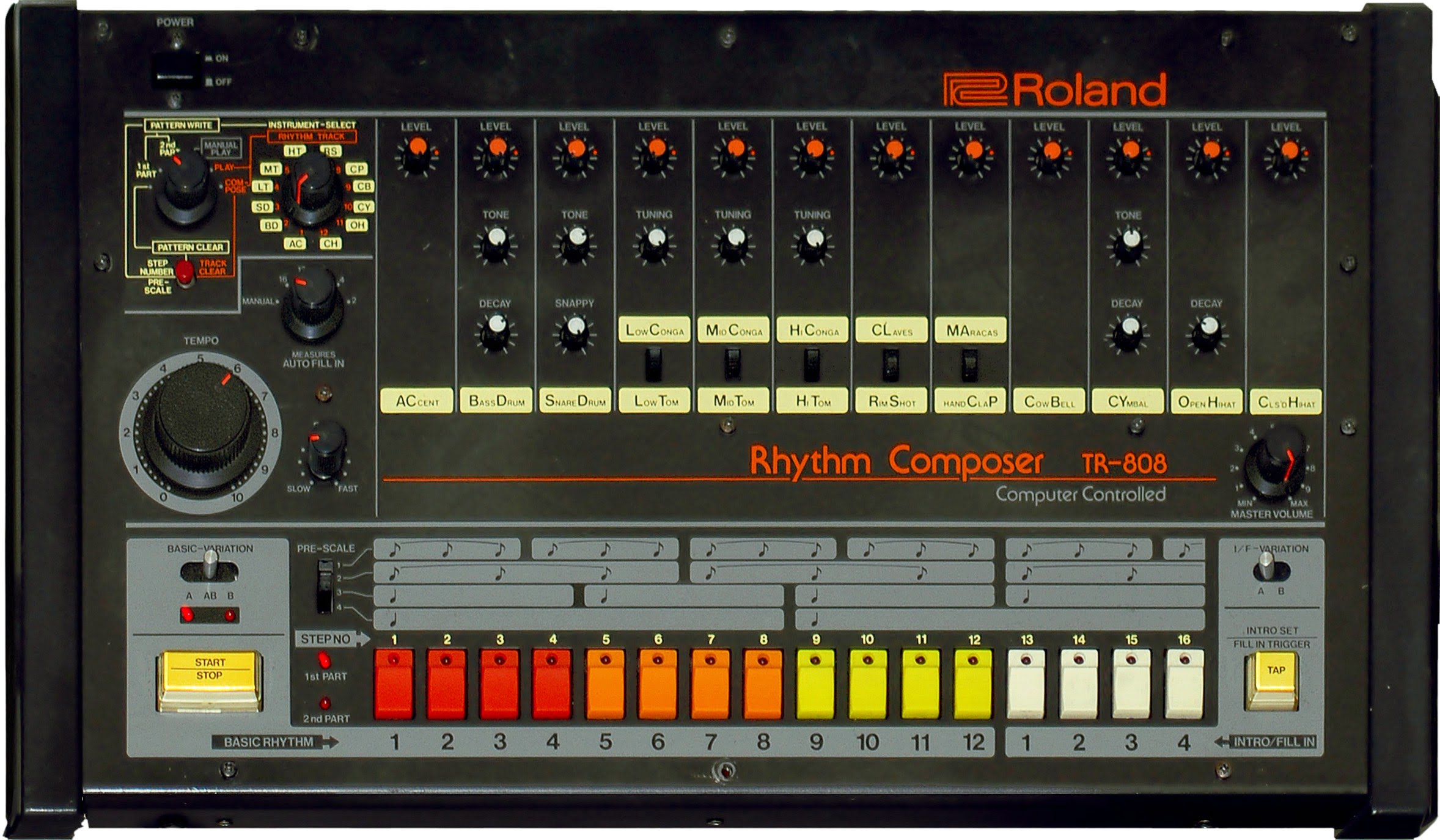

Whitney Houston – I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)

Roland TR-808

How many times have you heard a rapper shout “808!” and wondered what they were on about? So ubiquitous has the 808 sound become that we forget its origins. Introducing the Roland TR-808, famed for its instantly recognisable and oft-used drum sounds. Just listening to the opening bars of Whitney’s I Wanna Dance With Somebody says it all. Marvin Gaye’s Grammy-award winning Sexual Healing was one of the first tracks to showcase the 808. It cropped up on countless 80s hits, from Yazoo and Loose Ends to New Kids On The Block.

The TR-808 has been described as a ‘major interrupter’ in terms of its cultural impact. Roland founder, Ikutaro Kakehashi, actively set out to make instruments that were accessible, portable and affordable for general enthusiasts, at a time when many other manufacturers were pitching purely at the pros.

Its influence really cannot be overstated. There’s a band named after it, the Manchester group 808 State. There’s an album dedicated to it, Kanye West’s 808s & Heartbreak. There’s an official Spotify playlist devoted to tracks made with it, featuring Talking Heads, Shannon and Phil Collins. There’s even a documentary film of its life story, starring the crème de la crème of the music glitterati. Not bad for a small box that was in production for under four years at the turn of the 1980s.

Felix Rowe

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.