Ultravox Interview: ‘We were only two narcissists down but we still had three left’

By Classic Pop | January 9, 2020

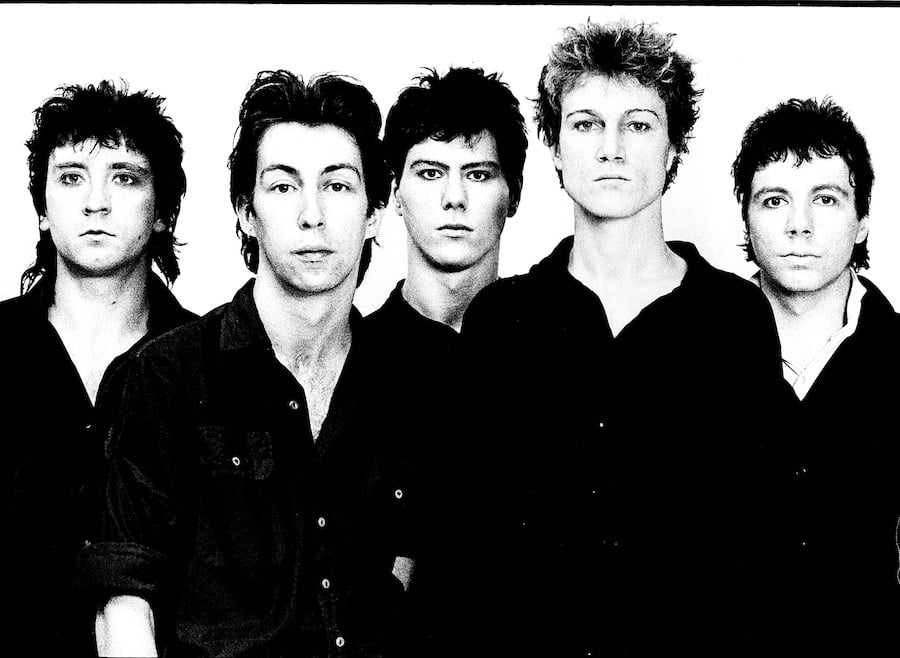

Wildly inventive, fearlessly experimental and ahead of their time, the first three Ultravox albums cleared a trail that many others would follow. Four of those who were there – John Foxx, Chris Cross, Warren Cann and Robin Simon – look back to the late 1970s. Jonathan Wright listens in…

Jonathan WrightWe often think of the musical culture of the 1980s as having been invented in the late 1970s, that time when post-punk experimentation collided with the moment New Romanticism escaped from London’s clubland, and synth-pop went on to conquer the world.

But you could just as easily begin the narrative on, say, 29 April 1967 at London’s Alexandra Palace.

This was the night Pink Floyd headlined The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream, a benefit concert-cum-happening for the counterculture newspaper International Times, which at that point was receiving unwanted police attention.

Among those in attendance, marvelling at this “distillation of magical things, all together in one place”, was Dennis Leigh, a teenager raised in Chorley, Lancashire.

“You met a new generation, impatient to change the world and expand all horizons – imagination, intellect, artistic ambitions, sex, romance, poetry, noise as music,” he remembers.

“No limits. Seeing [John] Lennon and others wandering about in the crowd, you realised that they were people, too, just as real as yourself, equally intrigued and bewildered. Everything seemed imminent somehow.” It was… “A glimpse of possibilities. I started making plans.”

These plans would, it’s no exaggeration to say, help to shape the musical landscape of the late 1970s and 1980s.

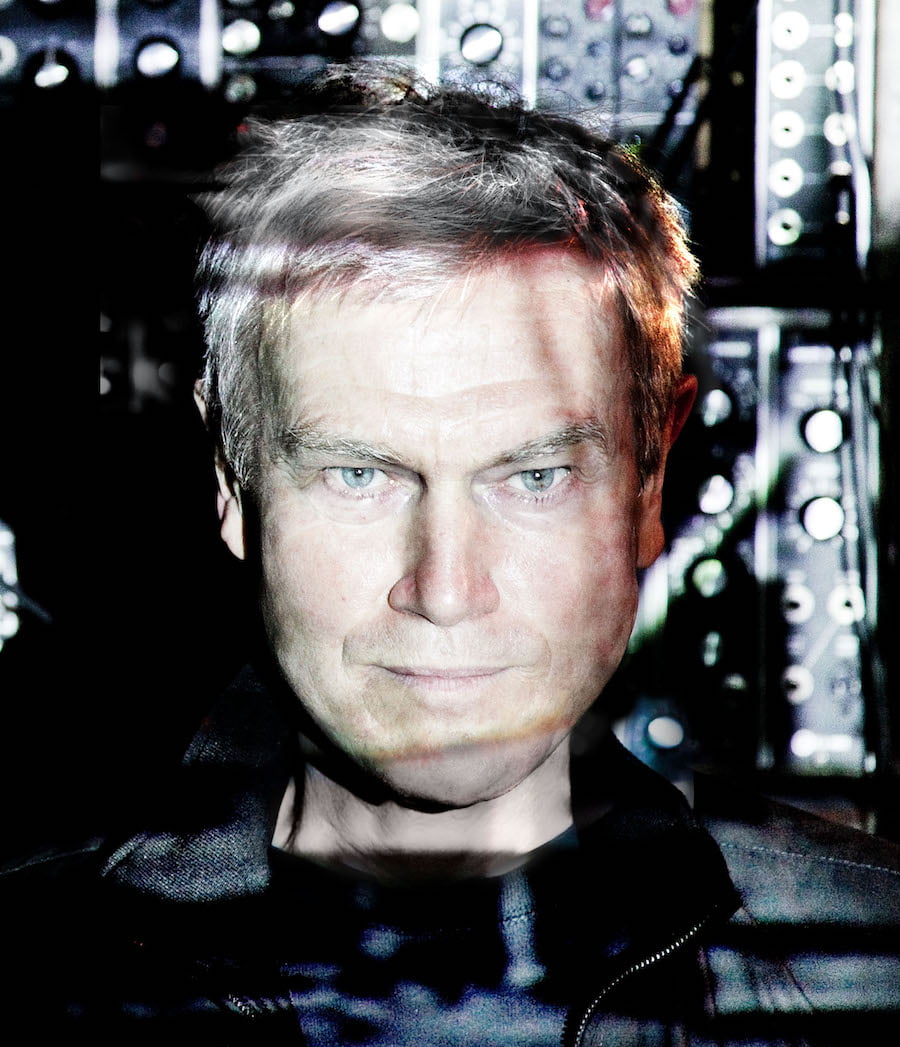

That’s because Dennis Leigh would reinvent himself as John Foxx, the frontman on the first three Ultravox albums – Ultravox!, Ha!-Ha!-Ha! (both 1977) and Systems Of Romance (1978) – and later a hugely influential solo electronic artist.

All three albums sold poorly on release but would have an enduring influence on, among others, Gary Numan, Duran Duran and, you might argue, Ultravox themselves, when the Midge Ure-fronted incarnation of the band enjoyed international commercial success with Vienna, which Ure still plays live to this day.

A tumble of ideas

But that’s getting ahead of the story. The band that would become Ultravox! began to coalesce in 1973, when Leigh, soon to be Foxx, a student at the Royal College of Art, went looking for musical collaborators and recruited Chris Cross (bass, real name Chris Allen), Stevie Shears (guitar), Warren Cann (drums) and multi-instrumentalist Billy Currie. In March 1975, then called Tiger Lily, the band released a single for Gull Records, a cover of the Fats Waller song Ain’t Misbehavin’ plus a Leigh original, Monkey Jive.

It was a record firmly rooted in the glam era, notably in the flipside’s strong Bryan Ferry/Roxy Music influence, yet the nascent Ultravox! were slowly finding their direction.

“Art, film and music were starting to interweave more, the timing was perfect,” remembers Chris Cross. “Dennis was the catalyst and a great instigator. The New York Dolls, Roxy, Bowie, Velvet U-Bahn [literally: Underground], Kraftwerk, Neu!, La Düsseldorf were all inspiring. The modern world was the gunpowder to our Sonic Gunpowder Plot.”

Foxx cites the importance of how radical and theoretical ideas from artistic and counter-cultural movements such as Dadaism, surrealism, the beats, pop art and, most especially, situationism played into what was going on in the mid-1970s, a “tumble of ideas, literature and talk”.

The mutation of Dennis Leigh into John Foxx was “a reboot” to help him cope with all this. “I needed someone more intelligent, better looking, better lit and more capable of dealing with mayhem,” he says.

“Never managed to live up to it, of course, but Foxxy has always been very useful. A naively perfected entity. A decent bit of conceptual sculpture, really. He still protects me from this world.”

Less highbrow was the way the band was drawn to the “sleazy side of glam” and, indeed, sleaziness in general. “Soho was where we played,” remembers Foxx. “The Marquee and King’s Cross became our base. The two most depraved bits of central London at the time.

“Prostitutes, drugs and strip clubs. King’s Cross was the first time I ever saw a woman take a piss in the street in broad daylight.

“As rehearsals finished at night in Albion Yard, we’d walk down the alleyway, past the familiar row of prostitutes entertaining clients – all busily on the job – and wish each other goodnight. Their voices were often a bit muffled.”

In 1976, having gone through various name changes, Ultravox! – Foxx: “the exclamation mark was a nod to Neu! who we admired, and the name resembling an electrical device, which we were” – signed to Island, largely on the strength of a fierce live show.

That autumn, they recorded an eponymous debut album with Brian Eno and Steve Lillywhite. It was released in February 1977, the same month as three seminal punk albums: Damned Damned Damned, The Saints’ (I’m) Stranded and Television’s Marquee Moon.

“Looking back now, it was an exciting time,” remembers Cross. “Something was changing and we hung on to its vapour trails.”

Glimpse into the future

The cover of Ultravox! shows the quintet standing in front of a grimy wall, below a neon sign of the band’s name. At first glance, it’s a simple image of the cityscapes through which the band were moving.

Yet while Ultravox! is the most straight-ahead rock’n’roll album the band ever made, less obviously it’s also an image that reflects Foxx’s interest in science fiction and, before anyone knew there was such a thing, cyberpunk.

“I was looking at the next stage of evolution, as we merged ourselves with new technologies – what would it

all feel like?” says Foxx, whose songs for the LP included I Want To Be A Machine.

“In trying to examine all this, I became aware of the need for a new combination of genres and ideas – a kind of romantically despairing sleaze mixed with sci-fi. Blade Runner hadn’t happened yet, so at that time there was no model of noir sci-fi.

“That thing I was pursuing was the difference between Kubrick’s 2001 and [Ridley Scott’s] Blade Runner or Alien – a sea change from a clean, orderly future world to a rainy, decaying, ultra high-tech sprawl.”

This need to look ahead also influenced the choice of Roxy Music synth-twiddler Brian Eno as co-producer, then as now seen as a pioneering figure.

“We got along extremely well with him and had innumerable long discussions with Brian about music, art and pretty much everything,” says Warren Cann.

“What excited us was we seemed to share many of the very same attitudes and opinions, but his thinking was far in advance of us. Our thoughts seemed to be all over the shop in a mad scramble, whereas his were so orderly and considered.”

That said, he adds, Eno’s “tangible influence” on Ultravox! was “negligible” because “his technical ability in the studio was not at all on the same plane as his conceptual abilities”.

In the end, Cann says: “We basically produced it ourselves and gave [sound engineer] Steve Lillywhite a co-production credit for his great success at refereeing us.”

Radical movement

Ultravox! was unleashed on a world where punk was about to break big. Foxx loved punk’s energy but understood early on that its three-chord aesthetic would become limiting. “You know, since art school, I’d been fascinated by the way all so-called radical movements evolve and decay,” he says.

“They start with a great idea, then inevitably erect rigid conventions, become ossified into conservatism, evolve a strict self-protective catechism, then the puritan prefects are out on patrol, shooting down anything that tries to jump the wall.”

Certainly, Ultravox! suffered some stinking reviews because the band were seen as too arty, inauthentic. Appearances can be deceptive.

“Ultravox were actually all working class, and more so than many bands at the time,” points out Foxx. “We had no managers, PR, or anything at all behind us – quite unlike everyone else.”

“We were there from Day One,” says Cann, “and had more real creative anarchy pulsing in our veins than boatloads of critics’ faves.”

But for all Ultravox! didn’t quite fit with punk, second album Ha!-Ha!-Ha!, recorded with Steve Lillywhite in the early summer of 1977, nevertheless comes across as infused with the energy of the year that the Sex Pistols gratuitously hijacked the jubilee with God Save The Queen.

- Read more: Ultravox – the complete guide

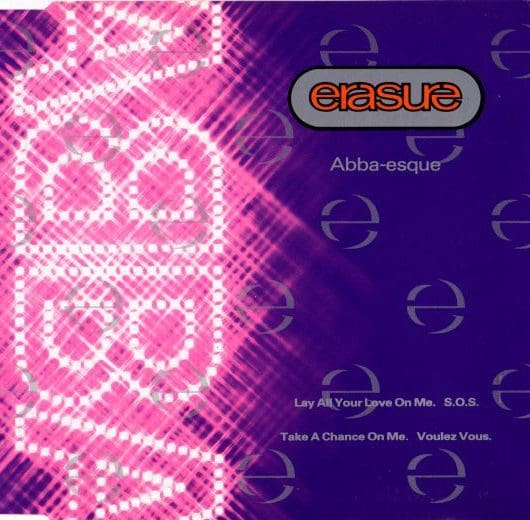

And the spirit of the times, too, considering the album’s single ROckWrok managed to sneak the sentiment “F*** like a dog, bite like a shark shark” past the BBC’s ever-watchful naughty-words committee, seemingly on account of Auntie not being able to make out the lyrics.

Ultravox! were moving on apace. Specifically, the band had purchased an ARP Odyssey synth and a Roland drum machine, and this new technology was beginning to make itself heard in the music. It’s a transition you can hear on Hiroshima Mon Amour.

On a single version released as a B-side in October 1977, it’s played essentially as a conventional rock song. The haunting LP version, though, is built atop a Roland drumbeat and features a haunting saxophone melody from CC of the band Gloria Mundi.

It really doesn’t seem too fanciful to suggest it’s a record where, in key respects, you can hear the sounds of post-punk and 1980s synth-pop being invented.

“Hiroshima Mon Amour focused everything I was trying to get to at that point,” says Foxx.

New possibilities

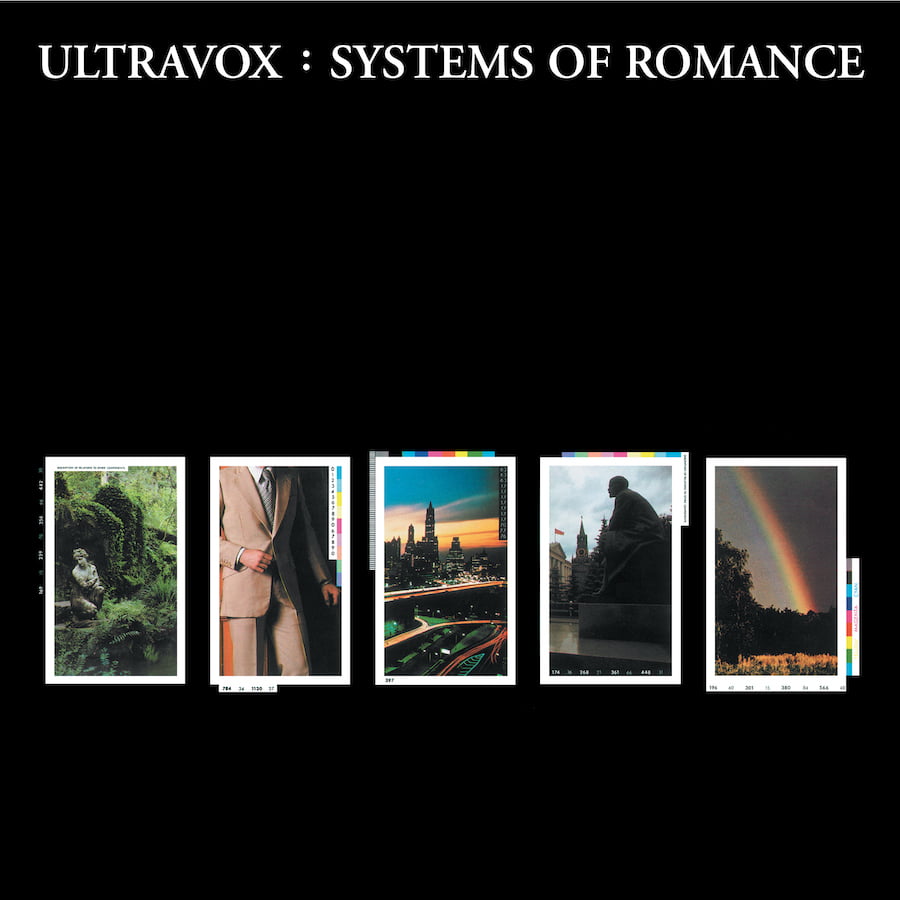

It was also the jumping-off point for the band’s third album, Systems Of Romance. “The table was cleared and we found ourselves in a place that no-one else occupied,” says Foxx.

“At that point, we’d consciously got rid of all the rock clichés, and any blues and rock Americanisms, and devised a new territory, mainly concerned with Europe.”

Reflecting this, the band opted to work with Conny Plank, whose credits included Kraftwerk and Neu!, at his studio in Cologne.

The what-if? question that underpins so much science fiction, and which weaves through the early history of Ultravox, was uppermost in Foxx’s mind: “What if America had never existed? What would Brit music look like and sound like if we’d looked to Europe instead? I felt exultant when I reached the point of asking myself that – and I suddenly knew what we had to invent.”

But not without a line-up change, as Robin Simon replaced Shears (who joined new wave band Cowboys International).

“You know, Robin has never been properly credited with the making of modern guitar,” says Foxx. “Everyone imagines guitars naturally sound as they do now, but they certainly didn’t – not before Robin.

“He incorporated radical effects into the sound and operation of guitar before anyone else, without losing ferocity. There was Rob and John McGeoch (Magazine, Siouxsie And The Banshees, Public Image), and that was it.”

“We never necessarily socialise that much or anything, but we seem to be on a wavelength when we do music,” says Simon, who has recently been working with Foxx again. As to the kinds of sounds Simon was going for on Systems: “It wasn’t exactly punk rock. I had echo, flange, all sorts of things, I had five or six [effects] pedals at the time.”

Simon says he encouraged Cross to begin using a synthesizer for bass parts, which changed the band’s sonic dynamics. “It was a sound that people probably hadn’t heard before in a band format,” he says.

“These were creative sessions,” he adds, where, “[Conny Plank] was interacting with the band, just letting it happen and recording what happened.”

- Read more: Making Ultravox’s Vienna

This tallies with Foxx’s memories. Systems Of Romance, he says, was an album where every member of Ultravox (they’d dropped the exclamation mark) was at the top of their game.

It’s also the Ultravox album that’s had the most enduring influence, both for looking towards Europe, and for the way it showed how bands could integrate both traditional instruments and electronica.

Listen to opener Slow Motion, with the aforementioned synthesized bass and guitar effects for proof of the latter point. Yet despite being born of such creative sessions, the album didn’t sell and, on 31 December 1978, Island dropped Ultravox.

The lava still flows

The Foxx-fronted Ultravox didn’t go out with a whimper, though. In early 1979, they embarked on their first US tour.

“We bought the cheapest tickets we could, crammed our equipment in the luggage hold as ‘excess baggage’, and rented a station wagon to drive ourselves from gig to gig, remembers Cann. “You really couldn’t have done it on any more of a shoestring than we did.”

Despite the lack of record company support, says Foxx, “The audiences got it. They understood what we were up to and loved it. America was excellent then – a real appetite for new, wild, exciting things, all across the country. You could feel the lift, the turning of the tides.”

Relations were strained, ironic considering Foxx had lately announced he had decided to live without emotions. “The last American tour was like the tail-end of the story of a volcano,” says Cross.

“The pre-eruption had built up and exploded gloriously for a while. Later, the lava was still flowing but we eventually suffocated in the ash.”

After the last show, near San Francisco, Foxx eventually quit. This was, he says, something he had planned to do from the beginning of the excursion, a decision and an announcement that made the tour “hellish” for all the sense that Ultravox were connecting with an audience.

According to Cann, the rest of the band informed him he couldn’t quit, because in fact he was fired – “I suppose that’s all a matter of perspective, isn’t it?”

You can speculate forever on what might have happened had Ultravox carried on with Foxx as frontman. What’s a matter of record is that John signed to Virgin and, in 1980, released the first album, Metamatic, in what’s been a fascinating career.

Simon, who couldn’t see much future in Ultravox, toured with Magazine in 1980. In August of the same year, the Midge Ure-fronted version of Ultravox had its first Top 30 hit, with Sleepwalk.

“At the end of the American tour we were only two narcissists down, but we still had three narcissists left,” jokes Cross of the decision to carry on, “and you really only need one of those to start a band.”

As for the band’s wider influence, the first proof that it might be lasting came early. In June 1979, the visceral synth-pop record Are “Friends” Electric?, hit No.1.

“[With Gary Numan] it was a similar thing to Joe Strummer hearing the Pistols [and forming The Clash], he adopted the synth-rock direction of Ultravox,” says Simon.

Tellingly, Billy Currie was in the band when Tubeway Army performed the song on The Old Grey Whistle Test.

“[We] made some major inroads on people who, at the time, equated the sound of a synthesizer only with ticky-tocky toy beeps and whistles,” says Cann, “because we’d slammed them against the back wall of the Marquee Club with their ears bleeding from the roar of a synth at full rip, right there at home with a Les Paul through Marshall stacks – still makes me smile.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!