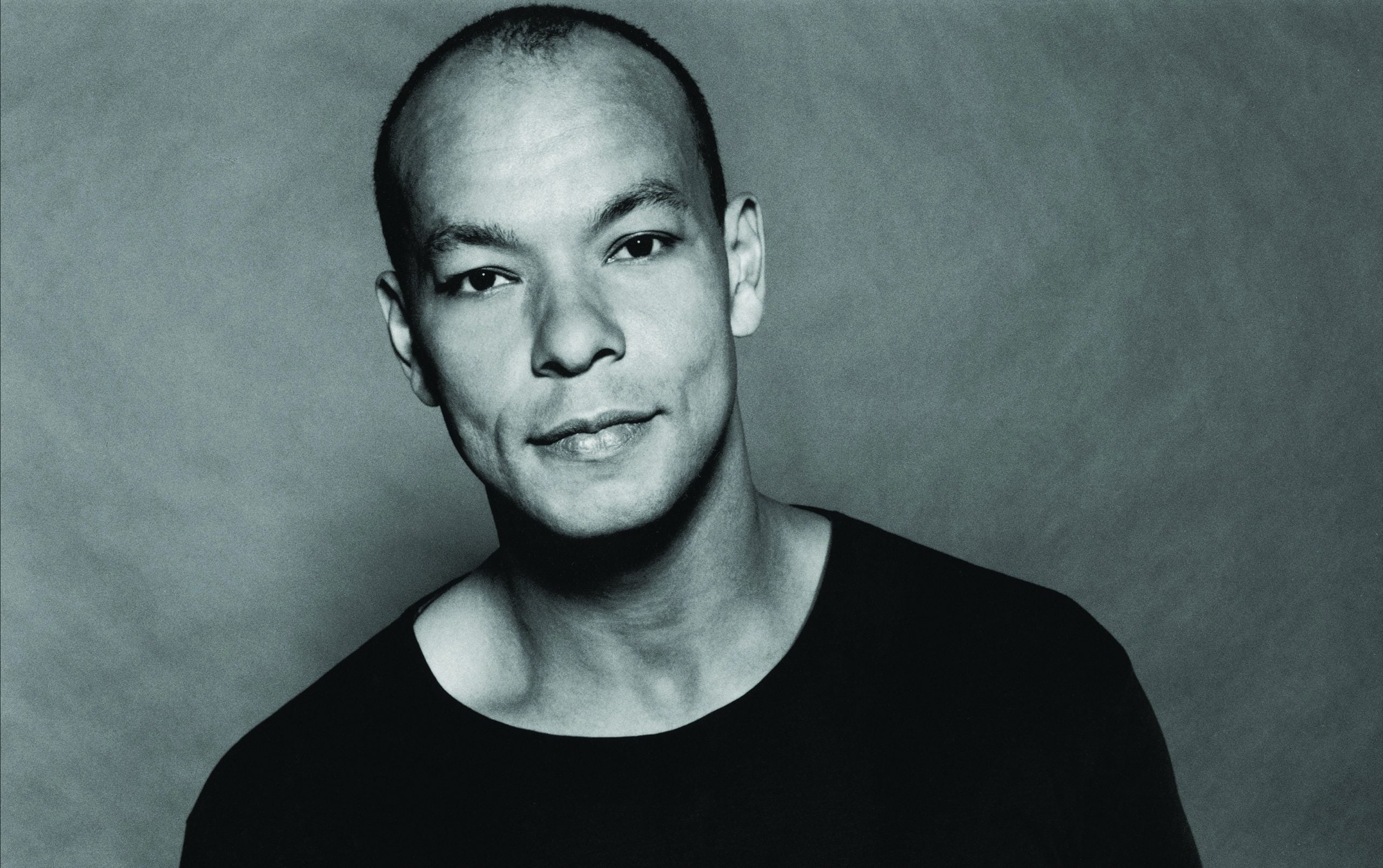

Fine Young Cannibals released just two albums in their short life, both of which have just received a long overdue reissue. Steve O’Brien talks to the band’s frontman.

Fine Young Cannibals formed in 1984 after bassist David Steele and guitarist Andy Cox – both former members of The Beat – advertised for a vocalist. Following eight months spent sifting through more than 500 audition tapes, they settled on 23-year-old Roland Gift, a uniquely handsome Brummie (in 1990, he was named by People magazine as one of the 50 most beautiful people in the world) with a killer voice who’d previously supported The Beat as part of his old band Akrylykz. Together, Fine Young Cannibals would win a BRIT award for Best British Group and enjoy five Top 10 hits. Their two albums, an eponymous debut and its follow-up, The Raw & The Cooked, are now getting an expanded and remastered release on CD and vinyl, courtesy of London Records.

Have you had the chance to relisten to those two Cannibals albums ahead of London’s reissue?

I go back to them fairly frequently. When I play live, it’s a mixture of Cannibals and new stuff, so there may be newer band members who need to learn the songs. So I’m not that far away from the songs, as it were.

The reissues are arriving with numerous rarities and unreleased tracks. Have you heard any songs that you regret not including on either of the albums first time round?

Not really. Sometimes when you release an album, you’re choosing from 15 songs and you’re only going to use 10 – it’s not that the other five aren’t any good, it’s just that they might not fit the statement you’re trying to make at that time. But it’s good to be able to have those songs available.

Your debut single, Johnny Come Home, was released six months before your first album and was a No.8 hit. Did your life change overnight?

I’d been on the dole before, so yeah, it was a complete 90-degree change. But it was also something I’d had my eye on. I’d had a false start, as I used to be in Akrylykz. I’d been in studios and released a couple of singles and been signed briefly, so I’d had a bit of experience.

What do you remember about the making of that first album?

There was a studio in Camden Mews, where we did Johnny…, and we liked it, but it was a bit small. The record company thought we’d better go to a better studio [for the album]. I’ve never been a fan of studios, I’ve always preferred going to a house or something like that, to record in. They all seem a bit like laboratories to me. A casual little place is as good as a big, posh expensive one. That proved to be the case, as they got us to record at this studio called Wessex Sound in Highbury. So we did another recording [of Johnny…] but it didn’t have what the original had, even though the timing was a bit out in certain places on the demo.

It took four years to release the follow-up, The Raw & The Cooked. Why the long wait?

I’m not sure. There were lots of little things. David and Andy were living in Birmingham when we did the first one, so there was that relocation thing. Although I was living in London at the time, it still could have affected how I worked, too, because I was used to going up to Birmingham for three days – we’d work on stuff together, then I’d come back.

What did producer David Z bring to the album?

There was just this assurance which is what you want from somebody in that position. You want them to be able to marshal the whole project, ‘cause that album was recorded all over the place. It’s good when someone’s a little bit apart from everybody else. They can look at it with fresh ears, as they’ve not been there for the whole creation of the song. Sometimes you can get a little bit lost in a song and not really recognise what’s really good and what’s not so good about it, especially if you’re not playing it live at first. A lot of those songs got better when they were played live.

That second album was well reviewed and was No.1 in both the UK and US, so why was it the last Cannibals recording?

It was more to do with stuff around the group. We had two managers, John Mostyn who managed us for everywhere excluding North America and Japan, and we had Tony Meilandt who managed us there. There was this singer [Simon Fowler] who had done some backing vocals for us and he was in Ocean Colour Scene and Moston left, saying, ‘I think I’ve found the new Beatles!’ Tony ended up dying alone in a hotel room from a drug overdose. When Tony became the sole manager he started messing with everybody’s minds. He was saying to David that me and Andy were going to get another bass player and saying the equivalent to Andy and something similar to me. It was almost as if part of the time he was a manager and part of the time he was in this parallel movie about being a manager!

The band officially split in 1992. How did the break up come about?

We’d been working at Olympic Studios in Barnes, and later that evening, the three of us turned up at this screening room to see a Bertolucci film, Stealing Beauty. Earlier in the day we all knew we were going to the screening but I didn’t mention it to David and Andy and they didn’t mention it to me either. So when we all showed up I just thought, ‘Oh, fuck this, this is pathetic.’ It wasn’t a very nice work environment when you’d previously been in a situation where you’d share stuff and now we’re being really cagey with each other. I don’t think any of us ever wanted to be in one of those bands where you turn up in your own limo. If we’d have been more experienced we’d have probably been able to get through that for the sake of keeping the show on the road. In some ways I think it’s good we didn’t, but in others, maybe there’s something to be said for toughing it out. But we did what we did. We came out of it okay, none of us had to see the repo man come for the Maserati.

Do you ever talk to Andy and David now?

Not really. Now and again, we might renegotiate our publishing deal but I don’t really see them.

So you can’t see the band reforming?

I don’t know what the point would be to reform. You can never say never, but nobody’s ever made an offer that couldn’t be refused. I’m open-minded, but I don’t think it’s likely.

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.