The first member of a-ha that Classic Pop meets, for a series of three separate interviews, in a fancy hotel on a chilly but sunny early-autumn day in Central London, is Paul Waaktaar-Savoy. Of course: the band’s guitarist and main songwriter, its quiet force, its brain.

“The talented one,” I jokingly venture, as we shake hands, because as any true a-ha diehard knows, the other two are hardly slouches when it comes to the construction of a-ha’s immaculately downcast pop.

“Don’t forget ‘handsome’,” he adds drolly, as might anyone who has had to spend 35 years sharing a stage with Magne Furuholmen and, especially, Morten Harket.

Somewhat reserved, Waaktaar-Savoy is wearing shades in the dim-lit bar of the Corinthia Hotel. He also talks in a low drawl, to lugubrious effect, but still the mood is lighter than the last time we met, in 2009. Then, on the release of a-ha’s ninth album, Foot Of The Mountain, all three of a-ha were interviewed together, and you could cut the atmosphere with a Norwegian hunting knife. “I don’t think we were focused on this one,” Harket reminisced sourly of the making of 1990’s East Of The Sun, West Of The Moon as the others tutted and sighed. “We were fighting too many demons, trying to avoid things. We weren’t together as a band.”

a-ha have spent much of their career conspicuously Not Being Together As A Band, pulling in different directions as they tried to satisfy their disparate demands and those of their various record companies. After their multi-million-selling debut album, 1985’s Hunting High And Low – the greatest album of synthesised-symphonic sorrow ever conceived by a putative boy band – there were doubts and tensions concerning how to proceed. Soon after, they seemed to scatter – figuratively and physically – creating and contributing from their own private universes.

It wasn’t until their latest album, MTV Unplugged – Summer Solstice, that they finally came full circle and worked on a record together again: not via email or isolated, individual sessions, but from being sat in the same room at the same time, arguably for the first time in 30 years.

“I think we followed technology, from our first album through our careers, and lately felt we could record anywhere – fragmented – but this album is back to our first five records, when we were always in the same studio together,” explains Waaktaar-Savoy.

Such a detached approach has been strange, particularly for him and Furuholmen, who have known each other since their early teens, growing up in Oslo. He recalls the partnership working successfully from the start as they spurred each other on in a spirit of “healthy competition”. The only time it hasn’t functioned well is when “stuff that isn’t about the music” gets in the way; “when stuff goes sideways,” as he puts it.

It’s 35 years since Waaktaar-Savoy and Furuholmen – who had formed the core of a Doors-y rock band called Bridges – acquired a charismatic frontman in Harket and left Norway for London to become a-ha.

Not that the wider world knew of them until 1985, when Take On Me blew up and reached No.1 across the globe, because up till then they were toiling behind the scenes, essaying a peculiarly Scandinavian form of bubbly electro-melancholy, with limited results. Not that they ever feared success wouldn’t one day come.

“It was awfully exciting, because there was always the possibility something would happen next week to give us a break,” says Waaktaar-Savoy, recalling that sense of optimism and blind hope. “We always had something to look forward to, even in the very early days.”

What, even when all three were sharing a squalid flat in Forest Hill, Southeast London, where there was no heating, they had to keep warm by turning the electric oven on, and a brown viscous substance would regularly ooze from the walls?

“No,” he laughs. “That was a low point.” Their next domicile – the floor of their rehearsal studio – was even worse. “There were no windows, and no light whatsoever. It was like an abyss.”

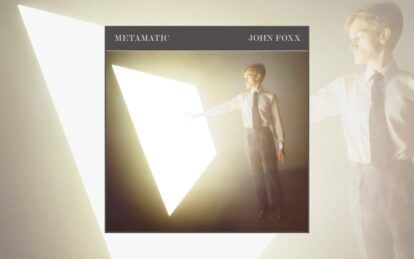

They would socialise with the glamorous New Romantic stars of the day, at nightspots like Camden Palace, where they would get in without paying, perhaps because Harket was earning a reputation as an ace face and clubs liked having him around. The other two, meanwhile, were having their ears turned by the era’s bright new synth sound.

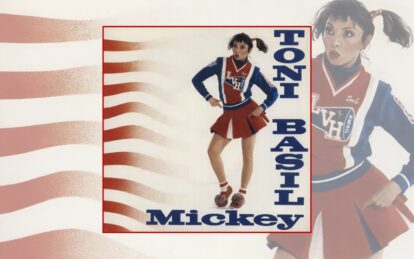

“We were Doors-inspired, but then we started hearing these concise pop hits – stuff like early Soft Cell, which sounded really punchy and hard-hitting on these great soundsystems that clubs had back then,” the guitarist says. “That changed our writing a lot.”

They began composing demos on acoustic guitar and would transfer the results – in the early hours of the morning at the studio of musician, producer and soon-to-be-manager John Ratcliff – to a LinnDrum machine and a Prophet 5 synth. There was never a plan to combine winning melodies and wintry desolation; that’s just what poured out of their pens and Harket’s voice. No matter where they were when inspiration hit, it would invariably have a gloomy quality. Take Here I Stand And Face The Rain: the climax to their debut album and the most exquisitely miserablist pop song since David Cassidy’s How Can I Be Sure, from the anguished choral flourishes to the dread-drenched lyric (“I fear for what tomorrow brings”), it was actually written in one of Europe’s party capitals, where they went with the spoils of their first publishing deal.

“Yeah, we got £1,500 each, which was huge for us, so the first thing we did was blow it on a trip to Tenerife,” Waaktaar-Savoy admits. “We went there to celebrate, and we ended up writing that song. It’s very… gothic.”

He agrees that the song – and others from Hunting High And Low such as The Blue Sky, Living A Boy’s Adventure Tale, The Sun Always Shines On TV and the title track – had unusual melodies that followed unexpected paths and were shot through with sadness (“Right from the start/I knew this world would break my heart,” as Harket wailed on I Dream Myself Alive).

The second half of the 80s were a blur of work (1986’s hastily assembled second album, the rockier Scoundrel Days, was mostly written on tour), shattering travel and the incessant demands of pop fame.

“We can only blame ourselves,” he says today. “We felt we had one chance to get a leg in the door so we weren’t too precious if people offered us an interview. We could have said ‘no’ more often, but we didn’t know Take On Me would take off. It was the birth of the video era. So we had this worldwide smash and everyone thought they knew exactly what we were all about.”

A-ha’s James Bond theme The Living Daylights (1987) and the following year’s Stay On These Roads album marked the peak of their first phase (aka The Pop Years). But lack of critical regard started to niggle at them. The last straw came at the Rock In Rio II festival in January 1991. There, a-ha drew a crowd of nearly 200,000 at the Maracana stadium, many more than the other performers, including George Michael, Prince and Guns N’ Roses. And yet still MTV – despite the award-winning video to Take On Me being a cornerstone of that music channel’s early output – refused to interview them. A-ha were, they felt, victims of their own pop ubiquity.

“We said, ‘See? Here’s what happens when you say yes to everything,’” recalls Waaktaar-Savoy. “We decided we had to be more selective, and to spend more time on music and less on travelling.”

There were two subsequent albums – East Of The Sun, West of the Moon and 1993’s Memorial Beach – after which, “driven crazy” as Waaktaar-Savoy puts it, by teen success – they went on hiatus. While they were away, people – music fans, even other musicians, from Coldplay to Morrissey and Oasis – seemed to get the memo: a-ha were worth taking seriously. On their return with 2000’s Minor Earth Major Sky, they were afforded a new-found respect. “Instead of us defending ourselves, journalists did it,” he says, vindicated.

The second member of a-ha that Classic Pop meets is Magne Furuholmen: the band’s keyboardist and second songwriter, the one most likely to use the words “zeitgeist” and “panoptic” and talk about Debbie Gibson one minute and Henrik Ibsen the next. The sometimes visual artist with the heavy heart, notwithstanding his early reputation as a-ha’s “cheeky one”.

“We were given those kind of caricatures early on: Paul was the quiet one, I was the joker and Morten was the ladies man. And there may be some little truths to that, but it’s not necessarily the whole image.”

Subverting their image has been a constant of a-ha’s career, all the way up to their new Summer Solstice album, recorded on the remote Norwegian island of Giske at Ocean Sound Studio. They made their name as an electro-pop band – this latest release of theirs features acoustic, deconstructed, “unplugged” iterations of their work. They were Smash Hits peers of Bros and Brother Beyond – and yet the guests on Summer Solstice include the more like-minded Alison Moyet, on a version of Summer Moved On, and Ian McCulloch of Echo & The Bunnymen, on renditions of Scoundrel Days and his own The Killing Moon.

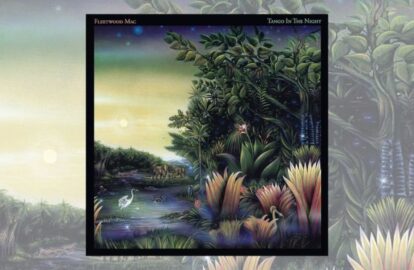

Yazoo and the Bunnymen offered examples in a-ha’s early days of how to combine charismatic, powerful vocals with electronically enhanced sonics: “emotionally charged music with programmed drums, and synthesizers creating a landscape to explore, one that would somehow be conducive to our angling towards the melancholy”, as Furuholmen captures it. But theirs, the Bunnymen especially, was a musical not a lifestyle influence.

“Growing up,” Furuholmen says, “we were timid Norwegians listening to serious music like The Doors. And ironically, some of the music we made [as Bridges] corresponded quite closely to that world. Their music spoke to us. But what we were excited about was music produced by people who were quite different to us. We didn’t want to live life on the edge at all.”

He sips from his tumbler of iced neat water and laughs. “That’s the fallacy of the music industry and also of certain people who follow the idea that unless you burn out and die young you have no credibility,” he declares, grandly. “I have to believe the opposite, otherwise I wouldn’t be here.”

He agrees that, by performing together and featuring two musical idols utilising “electronics with emotional power” from the early-80s, a-ha have come full circle with Summer Solstice.

What was it like, collaborating with their heroes?

“Alison was very courteous and sweet, but she has authority and charisma,” Furuholmen says. “Ian was an amazing force and it was a very fruitful experience. We think in the same theoretical ball-park, even if we lead different lives. He symbolises a time when he was the go-to guy for serious musical appreciation.”

All the way back to Here I Stand And Face The Rain – which roughly occupies the middle ground between David Cassidy and Decades by Joy Division – a-ha were making supremely dolorous music, even as they beamed from the cover of Smash Hits. The poppier end of their catalogue was represented by songs like Take On Me, but other ones, such as Here I Stand, “burned brightly within us”, even if they had to fight to have them included on their albums.

There might have been a three-year prehistory before Take On Me reached No.1 around the world, but still success seemed to come fast and hit them hard.

“It was quite sudden,” says the keyboardist, “and it was a revolution in our lives. We came from fairly stable middle-class backgrounds, and the dream of international attention for our music was what drove us.

“But success was a means to an end, a way of getting our music across, which is why we never really went ballistic in celebration or tried to perpetuate that success by going after what was successful. We challenged our own path.”

So they could have released more songs like Take On Me? “Well, not necessarily as successfully, but we could have tried and failed! Or tried and succeeded, but it would have put us in a different place to where we wanted to be.”

Take On Me was a sort of musical Trojan Horse that would allow a-ha to secrete all manner of dark despair into the charts. “That was the idea,” he replies, “but success swallows you up. The danger of success is that you end up hating the thing you love the most – making music. It becomes a pressure, delivering something successful.

“By the time Take On Me became a worldwide smash we were already looking in another direction,” he reveals. “We’d done that. Next? That’s hard to understand for record companies who helped put you there. They even have a term for it: ‘the disease’; ‘they have “the disease”’ – i.e. they don’t want to capitalise on their success, they won’t play ball and do all the cheesy promotion. We’re quite awkward pop stars in that respect. I’m quite proud of that, even if we did pay the price, losing territories like America… But it’s a price I’m happy to pay. We created a space for ourselves as less predictable and hopefully more meaningful, doing our own thing and making records that we believed in.

“We’ve always been a bit contrary,” he continues. “We never followed trends. We went all Americana on our fourth album [East Of The Sun…] as a reaction to all the synths, then we came back to the synths later on. It’s been a meandering career.”

Schizoid?

“I wouldn’t call it schizoid because underpinning it is a cohesiveness,” he replies. “But perhaps ‘probing’ and ‘paradoxical’ at times. Or ‘panoptic’: we draw inspiration from different places, whether it’s music, literature or art. Constant reassessment is one thing I’d like a-ha to be part of. You call it schizoid, but I like the fact that we can’t easily be put into one box.

“We’ve perhaps had a schizoid relationship with our career, both embracing and shunning it,” he allows. “We’ve tried to come to grips with fame ever since it happened. It’s like being thrown into a tumble drier: you get out with your hair all messed and super dizzy.”

Did fame test your relationship with Morten and Paul? He pauses before replying.

“It broke us as friends, and it broke us as people,” he says, quietly. “The early-90s were the aftershocks from the late-80s.”

They had to take a breather between 1994 and 2000, exhausted by it all. “There was a lot of battle fatigue and a sense of fighting a losing battle – it always came back to Morten’s cheekbones, and idiot questions about our early career and Piccadilly Circus being closed down by screaming girls. It was an amazing experience but it wasn’t what we were there for.”

In spite of their “broken” relationship, he still wanted to join in the reunion of the band in the new century.

“We weren’t so broken that we didn’t come back and still believe in it,” he agrees. “I was surprised to find I really enjoyed writing for a-ha and for Morten’s singing, and for me and Paul to interact in some way, although we haven’t got the kind of collaboration we had in the 80s when we were so close. But there is that fateful bond we share. I try not to think too much about all the stuff our musical journey brought us. The meaningful thing is to respond to what’s happening by being part of creating something that makes the world glow. When that happens, you feel that life has a purpose.”

The third member of a-ha that Classic Pop meets – saving the best, perhaps, and certainly the most beautiful, till last – is Morten Harket: the band’s lead singer and sometime songwriter, its vocal hero, its soul.

Even at 58, he really is something to behold. But a pretty vacant pop heartthrob he is not. The last time I interviewed him, for the Guardian in 2016, he spoke eloquently about Danish philosopher Kierkegaard and a-ha being appointed Knights of the 1st Class of the Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav for their contribution to Norwegian music. Oh, and did you know he was fascinated by botany and entomology and studied theology at university because he wanted to grow his hair long and would otherwise have to have had it cut for national service (he eventually did, in fact, become a soldier-recruit because he wanted “to find out who I was and what I felt about the army as a solution for society”)?

If the other two have, for over three decades, been dismayed by excessive attention to a-ha’s surface appeal, imagine what it must be like to be Harket, a deep thinker who is more Heidegger than Harry Styles. The first 10 minutes of our interview comprises a lengthily soliloquy on the priesthood, conscientious objection, Greek scripture, deific omniscience, and the nature of faith.

As he says, smiling, “I’m a curious fuck.” Meaning, he is terminally inquisitive, but he’s also curious in the sense of strange, an idiosyncratically atypical pop frontman and then some.

It’s well-known that he loved rock bands from Uriah Heep to The Doors growing up. Did he dream of being a latterday Jim Morrison fronting an 80s synth band?

“I never dreamed of being anyone but myself,” is his immediate response. He was similarly blown away by his first exposure to Jimi Hendrix – “Nothing had a greater impact on me, ever,” he says – and by seeing Waaktaar-Savoy and Furuholmen’s band Bridges circa 1981. “That was very powerful,” he says, “It struck me with tremendous force; a pivotal moment. I’d never seen anything like it in Norway.”

So a-ha could easily have become a West Coast-indebted, psych-inflected rock band?

“A-ha essentially is a rock band,” exclaims Harket, himself an ex-member of a band called Souldier Blue. “None of us were interested in pop music – ever.”

Moving to London with the band that became a-ha was a matter of expedience. “What happened was, we were charmed by what was going on in England and we were ready for change,” he says of the nascent synthpop scene. “I knew Bridges was the vehicle by which it would come. But I didn’t ask if I could join them – I didn’t want to sell myself to them; I’m not a car salesman. No, I needed for them to discover me. I knew that it would happen, and trusted that feeling.”

Did he have the same conviction when they were barely surviving on the breadline in London, virtually passing out from hunger?

“I never doubted it for a second.”

He tells a story about the time he, Paul and Mags visited the offices of Decca Records, the label that famously Turned Down The Beatles. Used to being inundated with unsolicited tapes from eager young bands, they asked the then-unknown trio to leave behind their cassette for the A&R team to listen to later at their leisure. A-ha flat-out refused.

“We only had three cassettes, we lived in Norway, we were only there for a week to strike contacts, so we couldn’t possibly leave the tape,” Harket explains. “It became very clear to me, not in a cocky way, but as a matter of fact: they needed to discover us.”

Not that a-ha, once Take On Me had announced their arrival so emphatically, needed much seeking out. By that stage, it was more a question of how to manage their ubiquity. Whether he liked it or not, Harket knew the best way to achieve market saturation with their sorrowful synthpop was via his looks.

“Not consciously, but it was my cheekbones, as has been underlined to death,” he says with a sigh. “Physical features were part of the pop scene. The look of the band, that type of focus, we had to deal with all the time. It was annoying.

“At the same time you understand it and accept that it’s there. But it masks the music and the work that you’re doing. Then you end up getting quite desperate at times. But cheekbones and stuff: it might be a superficial aspect, but I’m not knocking that area of connection because it’s partly what we are. It’s as authentic to what we are as any aspect. But obviously people – whether they’re 14-year-old girls or otherwise – are drawn to much more than that.”

Harket felt “misrepresented” by the media and dizzy from the pop carousel.

“It [teen press coverage] was so loud it dominated everything else,” he says. “We were deeply frustrated, but there was no time to dwell on it, on anything, because it was all so relentless. It never stopped.”

Wasn’t there any pleasure in pop success?

“I don’t think pleasure is the right word,” he says. Maybe the right word is “anhedonia”: an inability to derive pleasure from normal pleasurable activities.

“There was,” he suggests, “a lot of highly charged energy that just went on and on from many angles.

“But,” he adds, in case you were worried, “life has been very enjoyable. I’m just talking about the attention and the level of it and what it does to people around you. It does break people. Because you can’t change, but you have to in order to preserve who you are. It hasn’t changed me at all. It’s just exposed me to myself.”

And yet everyone who hasn’t experienced it – attention, adulation – wants it. “Yeah,” he says, “and nobody has a fucking clue what it actually is like.”

Comedian Jim Carrey said: “I think everybody should get rich and famous and do everything they ever dreamed of so they can see that it’s not the answer. You start to appreciate all the things you don’t want,” he agrees. “Because it’s not the way it’s perceived to be. But where it has brought joy is, you meet real people underneath it.”

Real people who appreciate a-ha’s contribution. A new paradigm: melodic Nordic melancholia. “It put a shining light on sadness,” Harket sums up a-ha’s music, and its mournful essence.

It’s well known in a-ha circles that, as a boy, Harket witnessed a plane crash, not discovering till much later that one of the people killed was Furuholmen’s jazz musician father. He doesn’t acknowledge this when I bring the subject up, but does say: “The way we talk about it, sadness is a bad thing. But it’s not, it’s a state of mind and heart where you contemplate things of value as opposed to being chirpy all the time and having a fake smile on your face, which isn’t genuine. We detest what isn’t genuine. People like truth. Our heart likes truth.”

And does this Unplugged album represent the truest version of a-ha?

“That’s a journalist question,” he says dismissively, still probing and parrying at the end of a day that has found a-ha reconciled to their past and finding new creative ways to forge a future.

“It’s not the truest but a different aspect. It exposes another side that has always been there and opens doors to yourself. Because you can only ever experience yourself anyway.”

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.