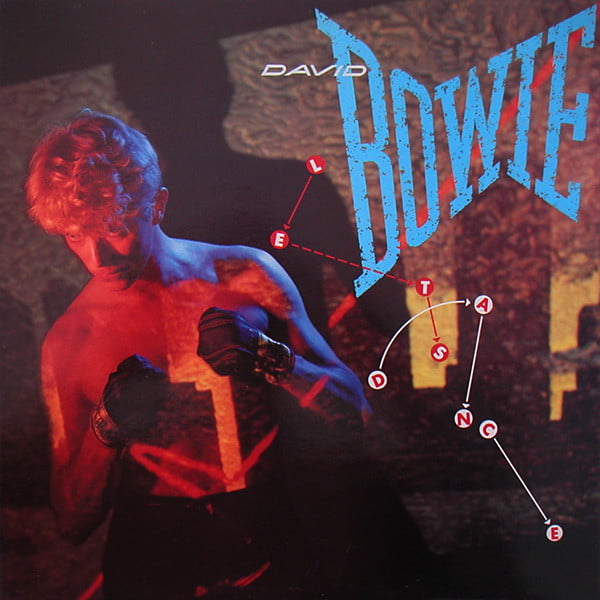

David Bowie: Let’s Dance cover

Widely scorned by long-term fans, David Bowie: Let’s Dance would become the singer’s bestselling record and one of the archetypal albums of the 1980s… By Andy Price

Though originally conceived as a Tony Visconti-produced continuation of Scary Monsters…’ art-rock sound, Bowie’s signing to EMI for a reported $17.5 million surely contributed to his decision to utilise the production skills of pop-funk Midas, Nile Rodgers.

Rodgers’ presence infused the resulting 1983 album, Let’s Dance, with a typically Chic-esque buoyancy and a bright summery sheen that made the mainstream pop-buying public – and the EMI executives – weak at the knees.

Bowie himself, unusually, played nothing instrumental on the record (despite conceiving many tracks acoustically, including the title track) and would later describe Let’s Dance as a “real singer’s album”. His voice – now comfortably locked into a lower register baritone – was perfectly suited to the new funk-pop aesthetic.

Musically, the record straddles rock, funk and disco, with a notable lack of any material too sonically (or lyrically) challenging.

Until this point, an artful and innovative streak had ran through David Bowie’s work. Even the previous stab at chart success, Young Americans, had an ironic air of alien detachment which came across in the Americana-trouncing title track and the politically charged Somebody Up There Likes Me.

David Bowie: Let’s Dance

Bowie’s outsider sensibility was never more striking than on his curtain-raising compositions. From the weary documentation of global catastrophe that opened Ziggy Stardust…; the lurching, mechanical arrival of the Thin White Duke on Station To Station’s title track; the quixotic shower of electronic noise that kickstarted Low and the squalling hysteria of It’s No Game – David Bowie had an undeniable knack for welcoming his listeners to his records with often challenging statements.

Modern Love, the track which launches Let’s Dance, was among the first tracks cut for the album and introduces the listener to a completely new incarnation of Bowie: the commercially minded hitmonger.

On any other album, his opening, spoken-word lyric: “I know when to go out, and when to stay in. Get things done”, would read like the portentous beginnings of an insight into a deranged mind, however here, among the lightweight synths and bouncy upbeat chords, Bowie’s delivery sounds like an off-the-cuff mutter.

To anyone still in any doubt, it soon became quite clear: David Bowie had made a record of uncomplicated populism.

Though this record (and the majority of Bowie’s 80s material, for that matter) has something of a Marmite reputation with Bowie scholars, for what it is, the effervescent Modern Love undoubtedly works as an explosion of light and colour that really does feel, strangely, like a ‘grand finale’-type track, as opposed to an opener.

David Bowie: Let’s Dance – China Girl

Everything but the kitchen sink is thrown into the mix… synths, sax and about 15 guitars collide. Perhaps, as several Bowie writers have theorised, the lyric could be read as apologetic, with such lines as: “There’s no sign of life” and the repeated use of the line “I never wave bye-bye”, it’s tempting to read the song as the formerly serious artist making a sorrowful confession about his new approach. This is almost overtly stated in the line: “It’s not really work, it’s just the power to charm”.

Though the verse implies a certain knowing depth, the hollow (but still infectious) chorus claims that everything pales in comparison to the vague concept of ‘modern love’ – with the allusions to getting to ‘the church on time’ and ‘god and man’ clearly alluding to a traditionally heterosexual marriage. John, I’m Only Dancing this is not.

Elsewhere, the lush production of Bowie’s version of the Iggy Pop song that he co-wrote in 1977, China Girl, gives way to the album’s only real hint of menace, with the bridge’s lyrics containing such shockingly incongruous lyrics as: “Visions of swastikas in my head/ Plans for everyone” and: “You shouldn’t mess with me, I’ll ruin everything you are” – reminding the listener of the original, darker version of the song, and of Bowie’s chemically fuelled globetrotting with Iggy.

The mix, however (complete with Nile’s parodic ‘oriental’-sounding riff), is densely packed. Carmine Rojas’ Under My Thumb-referencing bassline keeps the track’s momentum going, while Bowie’s absolutely incredible vocal performance has a large soundstage on which to shine.

The central piece of the album – the ubiquitous title track – remains a wonderful collision of world music, rock and funk which sounds as fresh today as it did in 1983. The dense arrangement was conceived by the last vestiges of David Bowie’s inventive spirit.

David Bowie: Let’s Dance – Modern Love

Nile Rodgers remembers in David Buckley’s Strange Fascination: “Having the synth bass with the Fender bass, David threw in little elements like that and gave it that edge and excitement that I probably wouldn’t have thought of.”

Despite being a curious jumble of ideas, the song is quite the most ‘danceable’ track Bowie ever produced, dominating the airwaves and giving Bowie his biggest commercial smash to date (aside from the frequently reissued Space Oddity), reaching No. 1 on both sides of the pond and figuring prominently in charts around the world.

Bowie had actually achieved his goal of making his most startling transformation to date: from the husk of an edgy, avant-garde figure came a family-friendly purveyor of disco fare.

As Carmine Rojas tells us, there was another unsung hero behind the scenes who was responsible for the track’s impact. “Bob Clearmountain really should get a lot of credit for the record’s sound as well,” Rojas recalls. “Bob, as an engineer, really captured what we were doing live in the room. He gets very little credit historically, but take it from me, he was vital to that record.”

Stevie Ray Vaughan, whose guitar playing dominates Let’s Dance, provides the most wonderful guitar part of the entire record, his blues-influenced riffery adding yet another facet to an already sonically kaleidoscopic track.

Despite the song being clearly designed to dance to, underneath lurks a quirky, intriguing lyric, with the act of dancing being the only recourse in the fear that “tonight is all”. We’re not just dancing in joyous abandon here, Bowie suggests we’re dancing away the pain of something much more bleak.

As Nicholas Pegg suggests in The Complete David Bowie, the song bears a thematic relationship with the bittersweet triumph of “Heroes”. The song’s deeper subtleties are underlined by the superb video, which become almost as omnipresent as the song itself, due to its heavy rotation on the fledgling MTV.

As the newly bleached blond Bowie casually strums away in an outback bar, a wonderful visual narrative underlines the plight of oppressed, over-worked and underpaid indigenous Australians, and also implied a withering criticism of corporate culture in general.

Though the video is widely loved, even by those that spurn the majority of Bowie’s 80s excess, the on-the-nose thematic point of it seems a tad hypocritical, as EMI’s new golden boy embarked on his highly lucrative assault on the charts.

After this opening salvo of expertly crafted hit-singles-in-waiting, the laid back stroll of Without You and the tensely rhythmic Ricochet, with a social-commentary-charged lyric fleetingly hint back to the more cerebral aspects of his former work, while Bowie’s cover of Metro’s Criminal World is a delightful listen, though takes some disappointing liberties with the original lyric.

David Bowie: Let’s Dance – Without You

The version of Cat People (Putting Out Fire) found on Let’s Dance is inferior to the gloomy original collaboration with Giorgio Moroder, but is still a strong song, particularly vocally, though does have the whiff of forced theatricality about it.

The only real howler in our estimation is the dreary flotsam of Shake It, which, unfortunately, signposts some of the lazier songwriting and generic production values on the ill-fated follow up.

Upon release, Let’s Dance was greeted with equal parts acclaim and contempt. Surprisingly, the occasionally irascible Charles Shaar Murray was delighted.

“It’s warm, strong, inspiring and useful. Let’s Dance is irresistible,” he espoused in the NME. “You should be ashamed to say you don’t love it.” Meanwhile, Dave Henderson at Sounds Magazine decried the record as being a “miserable and ramshackle affair. Lazy, emotionless and twee”. This critical polarity has never really gone away.

Evaluation of Let’s Dance switches quite dramatically from being perceived as the beginning of Bowie’s decline into mediocrity and creative impoverishment to being an immaculately well-produced and ultimately widely accessible pop record.

Perhaps the truth of the matter lurks somewhere in between. While aficionados of the innovation-led Berlin Trilogy and the angular paranoia of Scary Monsters… often balk at the commercially motivated direction of this album, many see it as somewhat ahead of its time, particularly in the wake of the resurgence in popularity of Nile Rodgers’ funk rhythms in modern pop.

Outside of the wider context of Bowie’s career and the ramifications that his new, commercial direction would have on it, we say that Let’s Dance remains a superb pop record, with the three singles in particular forever enshrined – for better or worse – as Bowie standards.

Read more: The Story Of The New Romantics

Read more: Making Visage

David Bowie: Let’s Dance – The Songs

Modern Love

Opening with a scratchy guitar, before the explosive propulsion of the beat comes in, Modern Love is the very definition of upbeat, with call-and-response vocals that owe a debt to Bowie’s beloved Little Richard. Despite being the jauntiest song Bowie had recorded in a long time, there’s an air of self-conscious admission, with the line: “It’s not really work, it’s just the power to charm,” perhaps alluding to Bowie’s new ambition of courting the Top 10 at the expense of his own art. Regardless of how you read it, Modern Love is, at heart, a bright and euphoric pop song that sets out his sonic stall for the rest of the decade.

China Girl

It’s quite surprising that here, on an album that so consciously attempted to seduce the mainstream, that Bowie would choose to highlight his association with Iggy Pop, one of rock’s most nefarious and unhinged figures. China Girl – a track that Bowie and Iggy wrote together in Berlin for 1977’s The Idiot, is reimagined here with a vibrant arrangement that’s among the record’s highlights, cannily laying (in many people’s minds) solo claim to a great song.

Bowie’s vocal here is among his strongest ever committed to record, sounding coolly confident and comedically ‘sexy’, while the danceable rhythm and oriental riff stick in the mind. Despite being a great song, the track’s video really hasn’t aged well. Despite some compelling visual moments, including a mock execution, the heavy use of cultural cliché reaches its apex when Bowie stretches his eyes in a feat of David Brent-esque cringe.

Let’s Dance

Kicking off with a step-by-step, ascending vocal part that recalls The Beatles’ Twist And Shout before launching into the utterly infectious – and aptly danceable – riff, Let’s Dance is Bowie’s new family- and chart-friendly persona in excelcis. Originally brought into the studio by Bowie with a folky/acoustic arrangement, the magic of Nile Rodgers transformed the track into perhaps one of Bowie’s most famous, and certainly among his most widely popular.

Bowie’s vocal is wonderfully dynamic as he soars, dips and rises over Rodger’s Chic-recalling funk rhythm, with a truly sublime bassline that works as a hook in its own right. Despite the impact of the single edit yielding an impressive transatlantic No. 1, The album cut is overlong and meandering, stretching out beyond the seven-minute mark. It doesn’t really matter, though, of course – for Bowie, now a major MTV star, the aim of the game was to get people out of their seats and onto the dancefloor.

Without You

The record’s first non-single (if you’re listening in the UK at least), Without You is more subdued than the opening trio of hits while still being a glacially smooth, pleasant listen. Once again, though, there’s a certain vacuity to the lyric, but Bowie’s vocal is silky smooth and utterly listenable: casually and loosely lathered over the rigid arrangement that features a memorable, repetitive bass motif. The aural allusions to Roxy Music’s output of the same period (particularly the previous year’s Avalon) seem fairly deliberate.

Ricochet

Perhaps the most interesting track on the record for Bowie scholars and devotees of his previous output, Ricochet was one of Bowie’s favourite compositions on Let’s Dance, featuring a lyric that explores the societal and cultural destitution wrought by 80s gung-ho capitalism (also a theme in the title track’s video).

Ricochet contains a wealth of countermelodies, backing vocals, curious monologues and expressions that are heavily distorted and barely coherent – just out of reach of the ear. The insistent, knocking rhythms and pulsing bass parts add a slightly uneven air to the song. It stands as the track that (with a slightly more stripped-back arrangement) could have easily fitted on Bowie’s previous record.

Criminal World

Bowie’s cover of Metro’s 1976 track is another lushly produced feat of serene magic from Nile Rodgers, with the spiky riff recalling China Girl and the silky synth underbed providing a warm ocean of sound for Bowie to vocally sail. Despite the track’s sonic charms, though, many critics disparage Bowie’s approach to this song – replacing the originally homoerotic lyrics with tamer, more generic male/female fare (perhaps with the aim of making it more palatable for the masses). This also coincided with Bowie publicly claiming that his politically charged 1972 statement of “I’m gay and I always have been”, was in fact a “major miscalculation”. For many, this represented an act of cultural abandonment.

Cat People (Putting Out Fire)

Released as a single prior to the album, this reworked version of a truly magnificent song switches gear somewhat. While the original, Giorgio Moroder collaboration (wonderfully used in the soundtrack to Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds) was a menacing, murky record of gradually rising Baal-recalling intensity, the Let’s Dance version reimagines the song as a camp, gothic piece that sounds like it wouldn’t be out of place in a production of The Phantom Of The Opera.

Regardless, the original melody, lyric and chord structure is thankfully retained, though Stevie Ray Vaughan’s guitar parts are totally incongruous here. For our money, though, the original single version is far and away the definitive version.

8 Shake It

Despite the debatable strengths of the previous seven tracks, any goodwill we might have left is sadly dissipated by the album’s finale. Shake It is really the point where Bowie’s immediate future – the sad relegation of songwriting craft and creative intention beneath boisterous, by-the-numbers production – is assured.

The disposable Shake It is often the track that Let’s Dance naysayers hold up in justification of their criticisms: it sounds like a half-arsed rehash of the title track, but with none of the ebullience and cool that made that track a huge hit. For the first time since the late 60s, Bowie pens a lyric that is flatly awful. Shake It marks the first definitive example of Bowie’s creative drought.

Enjoy this article on David Bowie: Let’s Dance? Then check out our feature on Scary Monsters

Check out David Bowie’s website here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.