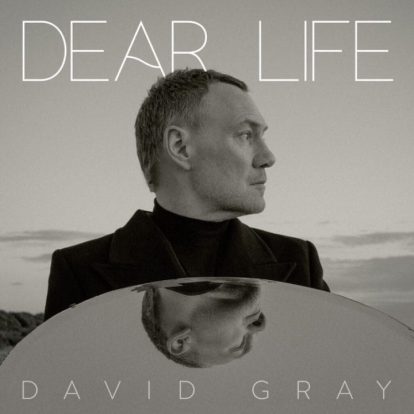

More than 20 years after White Ladder, David Gray returns with his new album Dear Life

David Gray once – quite literally – captured the sound of the city. His breakthrough album, White Ladder, was recorded in his bedroom in north-east London with such a DIY set-up that its biggest single, Babylon, features the sound of a car driving by outside. Some 26 years later, Gray is still inspired by the chaos of urbanity. Shortly before our interview, for instance, feeling rundown, he was caught in a torrential downpour while on London’s Marylebone Road, when an unexpected sight immediately lifted his mood.

“This Deliveroo driver came past on a bike, with his hands off the handlebars and he was singing his head off,” Gray laughs over video call. “In the pissing rain! You don’t really get that anywhere else. You get this mad stuff: these weird confluences of energy. I love the theatricality of the city. It’s endlessly replenishing; it’s never the same twice. But it is a demanding environment. It takes a lot from you to be there.”

So, for his meticulously crafted 13th album, the electronica-infused Dear Life, Gray decamped to his makeshift studio in rural Norfolk, where he relished the chance to escape the noise of the capital. He’s “a different person” in the countryside, Gray says: “I know I’m in a place where magic happens. I dial into the landscape, the speaking landscape: the geese, the sounds of the birds, the marshes, the beach, the sound of the sea in the distance. Those elements encourage a poeticism that’s different.”

Lighter Gray

That poeticism runs deep through Dear Life, which ebbs with the kind of mature, understated music Gray’s perfected ever since he went against the grain of Britpop’s maximalism in the early 1990s. Alongside producer Ben de Vries, with whom he worked on his previous two records, Gray decorates minimalist beats with ghostly instrumentation that underlines its wistful themes. He tentatively excavates relationships that have shifted into the past tense (After The Harvest), grief (the gorgeous Eyes Made Rain) and even the beauty of nature itself (Sunlight On Water).

For all the melancholia, though, there is plenty of lightness, too. The vivid Plus & Minus, featuring Essex singer-songwriter Talia Rae, is his most commercial-sounding single in years, while Fighting Talk sees him poke fun at his own earnestness: “Damn the lyric running round my head all afternoon/ Damn the swooning, sentimental tunesmith who wrote it.”

This lightness is evident throughout our hour-long interview: Gray is motormouthed, entertaining company, as fabulously profane as he is enthusiastic. Give him a topic and he’ll riff on it with Labrador-like energy. When we compliment the electronic elements on Dear Life, he explains excitedly that his nephew introduced him to a tiny drum machine called a Pocket Operator, which he approached with childlike wonder.

“It’s like a wafer,” he says, wide-eyed, before making a culinary suggestion that would make us think twice about having dinner round David Gray’s house: “You could probably spread a bit of pâté on there and have an electronic canapé! They’ve just got the crunchiest sounds and this very intuitive thing. You can really mangle the sounds – distort, delay, squish, filter. It’s really…”

Unable to express his feelings in words, he lets out an awe-inspired sigh.

Dear Life

His last few albums have been focused on analogue sounds, the exception being 2019’s Gold In A Brass Age, on which he placed the digital aspects front and centre. Here, the interplay is more subtle, as he blends live acoustic performances over “a rigid spine of order” provided by the songs’ electronic beats.

“A drum machine and an acoustic guitar,” he says, “when you get it right, is an amazing combination – that simplicity. If you can get the lyric to do what you need, if you can get the vocal to carry what it needs to, it’s very powerful. Working in a DIY way, as a bedroom artist, I still prefer that.”

Gray could be talking about the sparsely recorded White Ladder, which is perhaps no coincidence. He began work on Dear Life pre-pandemic, with production postponed by his Covid-delayed tour to mark the album’s 20th anniversary. Was his re-exploration of those songs an influence on Dear Life?

“It definitely was, though I couldn’t say to what extent, or how profoundly,” he says. When he recorded White Ladder with producers Iestyn Polson and Craig McClune, he adds, “the simplicity of what we did was remarkable. We didn’t have anything! All we had was a Roland Groovebox [production unit] and a bloody keyboard, a couple of guitars, a really dodgy vocal mic, a sampler and a computer.”

The result upended his fortunes. Gray had been dropped by EMI Records after White Ladder’s predecessor, Sell, Sell, Sell, his third album, didn’t exactly live up to its title. He released White Ladder via his own IHT Records; the album went on to shift seven million copies, edging to UK No.1 over two-and-a-half years thanks to word of mouth.

“Churning Emotion”

Gray has leveraged this success to follow his own muse, a journey that has often taken him towards bruised balladry rather than karaoke anthems in the making.

His last album, 2021’s Skellig, stripped his already spartan formula down to its barest elements and was inspired by an Irish island once inhabited by medieval monks. If Dear Life represents a return to the commerciality of White Ladder, it has been hard-won. In a statement accompanying the record, he explained: “The previous few years had seen a fair amount of tumult and upheaval in my life, and there have been some tough goodbyes.”

Gray continues: “I’ve had some very profound relationships in my musical career and some of those relationships ended over this last period of time. It threw everything up into the air and there was a long process of extrication, which was heartbreakingly difficult and incredibly stressful at times. And then there’s stuff in my personal life. Shit happens, especially when you get older and you’re sort of in ‘Sniper’s Alley’. Things happen that do pull the floor out from underneath everything. I think these births, death and goodbyes, they shake you up. They shake you back into more of a state of openness and humility, hopefully.”

The resulting “churning emotion”, he says, is rich with material: “I noticed that songs just sprang from nowhere, and I seem to be saying something that had been bottled up for a while.”

Picture credit: Robin Grierson

Younger Voices

Gray’s focus on endings might overwhelm Dear Life, were it not for the album’s youthful playfulness. He tinkered about with Plus & Minus for two decades before Talia Rae helped him unlock its potential. His manager met the Gen-Z singer, who’s around the same age as the track, when she performed at an industry dinner in New York (“nightmare gig,” Gray quips). Impressed, the manager struck up a conversation and it emerged that she was currently “obsessed” with White Ladder.

“It was like a serendipitous thing,” says Gray, who’d struggled to find a vocalist who could reach the song’s low notes. “Working with her has been so sweet. She’s right at the beginning of her… let’s not call it a ‘journey’. Her path through life! She’s at the beginning. Her eyes are wide. It’s great because she’s taking it all in. Youthful enthusiasm.”

Completing the trifecta of younger assistants – along with Rae and the nephew who introduced him to that wafer-like drum machine – Gray’s teenage daughter Florence sings on tracks such as Fighting Talk. He clearly enjoyed recording with his own flesh and blood, though admits with a laugh: “Unfortunately, I’m not the easiest person to please. I’m not very good at lying for convenience sake. It was quite demanding.”

Of course, there’s always been levity in Gray’s work – even the aching White Ladder concluded with a cheeky acoustic cover of Soft Cell’s Say Hello, Wave Goodbye. He’s a fan of electro and synth-pop in general: “When you listen to a lot of The Human League or Depeche Mode, they sound absolutely fucking amazing because there’s nothing going on. You’ve just got a couple of synths churning and a little drum machine. There’s so much space for the richness of the sound.”

Electric Dreams

Gray coveted the 1981 Soft Cell album Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret, which featured Say Hello, Wave Goodbye, in his early teens. He saw the late singer-songwriter Bryan Glancy and Mark Burgess of The Chameleons perform an acoustic version of the track in the 90s and was so blown away that he borrowed the idea. Soft Cell’s Marc Almond and David Ball were, in turn, impressed by his take: “I added another chord to the chorus, which they congratulated me on.” In a gruff northern accent, with a jokily begrudging tone, he recalls them noting, “‘You added a B minor! It sounds so much better!’” It’s these “confluences of energy”, as he said earlier, that made White Ladder such a success, and which define Dear Life, too.

“My life’s been more in balance,” Gray says. “I’ve had more time to do things that I wanted to do. It’s very easy to honour all your responsibilities, whether they’re familial or work or whatever they are, but sometimes it’s hard to build yourself into the mix. This is a common middle-aged problem. You kind of get squeezed out of your own life, and then…”

He trails off, before plucking brightness from the melancholia once more: “I’ve made a concerted effort to try to build some time in to do the things I like to do. To be in Norfolk, to breathe the air, to be outside, to take in this sustenance, this kind of energy. And that has led to a buoyant feeling. I’m very, very alive. I’m really, really enjoying what I do.”

For the latest David Gray news, click here

Words by Jordan Bassett + Featured image credit: Robin Grierson

Subscribe to Classic Pop magazine here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.