One of the UK’s most revered guitarists, Johnny Marr helped propel The Smiths to indie rock greatness before building a prolific solo career

The Smiths (1984)

Six years after first meeting at a Patti Smith gig, Johnny Marr and Morrissey debuted the songwriting partnership that many 80s indie fans consider to be akin to Lennon and McCartney’s. And on a record which practically reinvented the traditional guitar band, too. However, not everyone saw The Smiths’ potential. Manchester’s finest, who, of course, also included bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce, were turned down by both EMI and Factory Records. And Geoff Travis, boss of their home label Rough Trade, only agreed to listen to their demo once Marr pinned him down to a swivel chair.

The recording of their self-titled debut wasn’t exactly plain sailing either. Early sessions produced by The Teardrop Explodes’ guitarist Troy Tate were abandoned, with both the quartet and the record company unhappy at their unpolished nature. Morrissey also wanted to scrap the finished product overseen by ex-Roxy Music bassist John Porter. Not that he made such concerns public, claiming to Melody Maker that “I am ready to be burned at the stake in total defence of it.” Marr soon proved he could be just as self-aggrandising, too, bragging to The Face that, “For a lot of people, we’re the event of the decade.”

To be fair, that was no doubt true for those transfixed by Morrissey’s iconic gladioli-waving performance on Top Of The Pops: in a sign of things to come, This Charming Man didn’t get a studio album home. And while The Smiths is regarded as the least essential of the group’s four studio LPs, there’s still plenty to justify such hype.

Opener Reel Around The Fountain, a deeply melancholic six-minute tale of a formative sexual encounter steeped in ambiguity, perfectly set the tone for the group’s entire career.

Home to one of their most iconic lines (“Oh, Manchester, so much to answer for”), the controversial Suffer Little Children is a haunting portrait of the Moors murders which proved The Smiths were willing to confront subjects their peers wouldn’t even dare tiptoe around.

Referencing everything from Leonard Cohen to kitchen sink drama A Taste Of Honey, debut single Hand In Glove highlighted how they were also drawing cultural influences from a completely different well.

While Morrissey’s disaffected vocals and lyrical idiosyncrasies inevitably took centre stage, Marr is just as integral to the record, his shimmering guitar showcasing an incomparable understanding of melody and space. It would only get more brilliantly subversive.

Hatful Of Hollow (1984)

Although only issued nine months after their debut, Hatful Of Hollow already resembled an alternative Greatest Hits, thanks to the four classic singles which never made it onto a studio effort.

Musical marriage deterrent William, It Was Really Nothing, Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now (remarkably, the first of only three occasions that The Smiths entered the UK Top 10) and the glorious happy-sad jangle pop of This Charming Man have all deservedly become part of indie folklore since.

But it’s unarguably How Soon Is Now? that’s become widely accepted as their finest hour, with Marr’s chugging tremolo and widescreen slide guitars majestically underpinning Moz’s mockery of teen angst.

Elsewhere, there’s a collection of B-sides (including Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want) and an alternative mix of their debut single Hand In Glove. The 10 recordings taken from BBC Radio 1 sessions with John Peel and David Jensen, including the otherwise unreleased This Night Has Opened My Eyes, hint at what the Tate-produced debut might have sounded like.

The Smiths, or rather the group’s labels, became famous for milking their slim back catalogue. But Hatful Of Hollow is one of the few compilations which justifies its existence.

Meat Is Murder (1985)

“It felt like all the grown ups had left us and let us get along with doing our thing on our own,” Marr later told Hotpress about The Smiths’ entirely self-produced second studio album. The fact that Meat Is Murder knocked Springsteen’s Born In The U.S.A. off the UK No.1 spot proved they were even more effective when masters of their own destiny.

Of course, the Mancunians did draw upon the engineering talents of Stephen Street, cementing a working relationship that would extend into Morrissey’s solo career. But its nine songs, the majority of which originated in their guitarist’s Earl’s Court flat, is undeniably the sound of a band unwilling to compromise. Just listen to the deeply oppressive title track, a six-minute militant pro-vegetarianism anthem bookended by a disturbing cacophony of noises which appear to stem from an abattoir. It’s little wonder that the indie generation were forever scared off their festively sliced turkey.

Nowhere Fast foreshadows the distaste for the royals that would define studio album number three, while opener The Headmaster Ritual is a scathing critique of England’s education system (“Belligerent ghouls run Manchester schools”) which showed that even with their US profile growing, The Smiths were still determined to keep things local.

As always, Marr makes his presence heard, kicking off the latter with a kinetic dual-Rickenbacker riff self-described as the missing link between MC5 and Joni Mitchell.

Elsewhere, he throws things back to glam’s heyday on the propulsive What She Said, serves up the kind of slinky licks that Chic would be proud of on corporal punishment diatribe Barbarism Begins At Home and channels the hip-swivelling rockabilly of vintage Elvis on Rusholme Ruffians, a meditation on teenage violence which also no doubt deterred the indie generation from ever stepping foot inside a funfair, too.

Marr still gets to play the king of jangle to Morrissey’s master of malaise, none more so than on I Want The One I Can’t Have, a tale of unrequited love which eschews the usual cynicism for something approaching genuine yearn (“A double bed and a stalwart lover for sure/ These are the riches of the poor”). The group’s third release in just under a year could have run the risk of overkill. Instead, it left their fans wanting even more.

The Queen Is Dead (1986)

Of course, fans of The Smiths had to wait a little longer than expected for studio LP number three: a dispute between the band and their Rough Trade label resulted in a nine-month gap between first taster The Boy With The Thorn In His Side and its parent album.

The Queen Is Dead alludes to this spat on Frankly, Mr. Shankly, a jaunty potshot at label boss Geoff Travis (“You are a flatulent pain in the arse”) which briefly suggested that Morrissey had swapped his witty literate barbs for juvenile playground insults.

The mainstream media also get it in the neck on Bigmouth Strikes Again, a Rolling Stones-inspired display of self-awareness. Likewise, the royal family on the thunderous title track in which pop’s proudest anti-monarchist lives out his Buckingham Palace-trespassing fantasy.

Largely conceived at Marr’s new Bowdon home, The Queen Is Dead isn’t purely a musical vendetta, though.

Indeed, the Mancunians get relatively frivolous on cross-dressing character study Vicar In A Tutu and questionably themed closer Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others.

Morrissey’s uncanny ability to veer from the ridiculous to the sublime is also showcased on I Know It’s Over, one of his more beautifully melancholic displays of abject misery, and There Is A Light That Never Goes Out, a stunning tragi-romance that Marr described to Select as “the best song I’d ever heard.”

The guitarist is on sparkling musical form himself, whether it’s creating the latter’s haunting synth-string section, channelling The Stooges on Never Had No One Ever or soundtracking his bandmate’s Oscar Wilde-referencing thoughts on plagiarism with a simple yet deeply wistful riff on the famously misspelled Cemetry Gates.

“You progress only when you wonder if an abnormally scientific genius would approve – and this is the leap The Smiths took with The Queen Is Dead,” Moz remarked in the liner notes for its 2017 reissue.

It’s one of his few latter-day statements that no one can take umbrage with.

The World Won’t Listen (1987)

The UK alternative to North America’s more expansive Louder Than Bombs, The World Won’t Listen handily gave all The Smiths’ one-off singles and the pick of their B-sides from 1985-87 a permanent home. And as with the similarly themed Hatful Of Hollow, the set boasts some of the Mancs’ finest moments.

Produced entirely by Marr in a band first, Shoplifters Of The World Unite incurred the wrath of the nation’s supermarket bosses in the form of a reverb-drenched call to arms which evoked classic T-Rex. Reportedly inspired by Steve Wright’s playing of Wham! immediately after a Chernobyl news report, Panicbirthed the iconic line “Hang the DJ.”

While clocking in at just over two minutes Shakespeare’s Sister is arguably their punchiest single, an audacious blend of Spaghetti Western twangs, barroom piano and withering putdowns about the validity of acoustic guitarists.

Of course, the holy grail for The Smiths acolytes was the previously unreleased You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet, Baby, another record company tirade later transformed into a glorious burst of power pop on Kirsty MacColl’s second studio album, Kite.

Perhaps unnecessary at the time, The World Won’t Listen now serves as a vital document of the band’s in-between days.

Strangeways, Here We Come (1987)

Although there’d been plenty of upheaval before heading into the studio – Rourke was temporarily dismissed and fifth member Craig Gannon barely lasted nine months – the sessions for The Smiths’ fourth studio LP ran pretty smoothly. Joyce even told the BBC it was “a great experience.” However, by the time it hit the shelves in September 1987, indie pop’s biggest heroes had split.

Musical differences was the general party line, with Marr becoming exasperated at Morrissey’s choice of covers – Cilla Black’s Work Is A Four-Letter Word apparently the final straw. Unexpected swansong Strangeways, Here We Come strongly hints at a need to distance himself from The Smiths’ “jingle-jangle” sound, too.The creeping ska of opener A Rush And A Push And The Land Is Ours remarkably doesn’t feature a single guitar.

In stark contrast, the gloriously titled Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before contains Marr’s first ever solo. And on closer I Won’t Share You, his most notable contribution is on a newly discovered autoharp.

Yet, serving as co-producer alongside a promoted Street, Moz also seemed to be on the same page, taking to the piano himself on the fatalistic Death Of A Disco Dancer and ignoring Joyce and Rourke’s disdain over the use of a drum machine on the Bowie-esque I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish. He even agreed with Marr, that their unexpected swansong is their true magnum opus.

Whatever the reason for their premature split, Strangeways ensured that both figureheads went out with a bang. Paint A Vulgar Picture proved no one could skewer the music industry sharper than Moz (“Re-issue, re-package, re-package/ Re-evaluate the songs,” he sings, foreshadowing WEA’s future handling of their works in the process). While flitting from bright and breezy (Girlfriend In A Coma) to achingly sad (Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me), Marr’s guitarwork is as masterful as ever.

The Smiths’ story may have been short-lived, but their legacy remains never-ending.

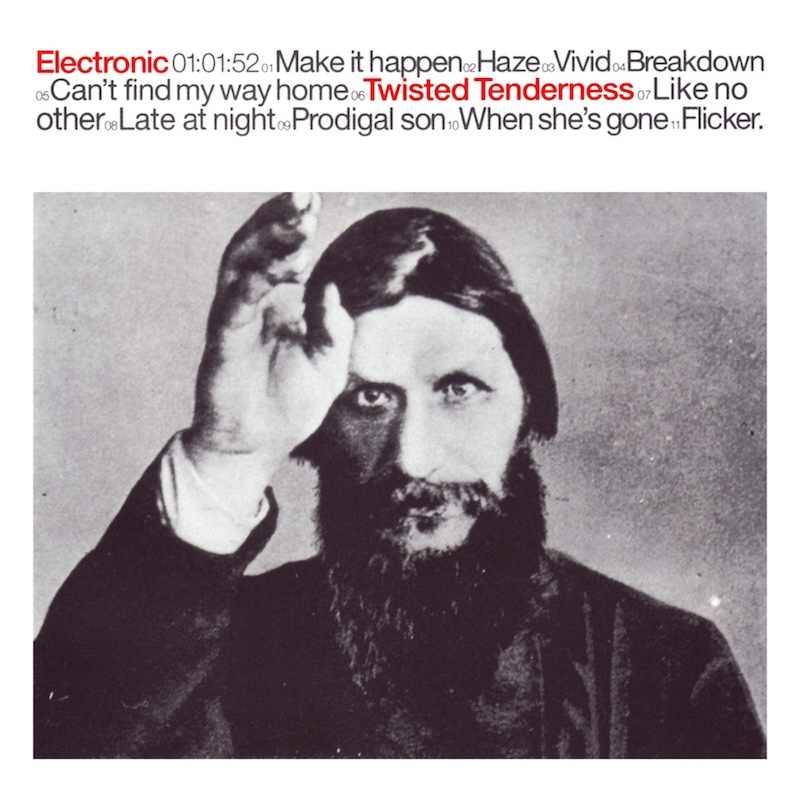

Electronic (1991)

After short stints with The Pretenders and The The as well as guest appearances playing for Kirsty MacColl and Talking Heads, Marr formed a supergroup with another Mancunian hero. “A post-industrial doom merchant who wore jackboots,” had been his first impression of New Order’s Bernard Sumner back in the early 80s. “A stuck-up little twat who lived in Altrincham” was how he was viewed in return. But luckily, after working together on Quando Quango’s one-album wonder Pigs + Battleships, the pair realised they’d been more judgemental than a Morrissey memoir.

With The Smiths disbanded and Sumner struggling with an eventually shelved solo album designed to show his bandmates the merits of programmed synths, the stars aligned for a collaborative effort. Not that they initially shouted about it from the rooftops. Concerned about their reputations preceding them, they’d planned to debut Electronic with various white label releases.

Of course, word had already got out long before first single Getting Away With It became an instant classic. Also featuring ABC’s David Palmer, The Art Of Noise’s Anne Dudley and the unmistakable tones of Pet Shop Boys’ Neil Tennant, the all-star line-up combined airy synth-pop with a delicious skewering of a certain miserabilist’s persona (“I’ve been walking in the rain just to get wet on purpose”).

The No.12 hit doesn’t actually appear on the LP, but there are still plenty of other gems where that came from: Top 10 chart infiltrator Get The Message bridges the gap between their two bands even more effectively, its jangly guitars and emphatic beats complemented by a powerful vocal coda from Primal Scream regular Denise Johnson. “The best song I’ve written,” Marr later claimed to the BBC.

The Patience Of A Saint also utilises Tennant for a sardonic duet (“Why should I care? I’d rather watch drying paint”) which recalls the blissed-out house of The Beloved.

The dancefloor-friendly album is bookended by two rebuttals to the criminalising of rave, with opener Idiot Country suggesting that Sumner had taken rapping advice from John Barnes and closer Feel Every Beat offering a welcome sense of hope.

With Factory Records folding a year later, Electronic is perhaps its last truly essential release.

Raise The Pressure (1996)

Electronic opened up their supergroup to another bona fide legend on their aptly titled difficult second album. Indeed, the one and only Karl Bartos, a man who tore up the contemporary pop playbook as one-quarter of Düsseldorf revolutionaries Kraftwerk, performed on all 13 tracks and co-wrote six. So it’s something of a surprise that Raise The Pressure is less synthier than its predecessor.

The German, who was invited to collaborate via the very 90s method of fax, still makes his presence heard. See the flickering electronic workout of Dark Angel, the synth-funk leanings of the autobiographical Second Nature and acidic squelches that permeate Until The End Of Time, the latter perhaps the closest the duo ventured into the kind of warehouse rave their debut seemed determined to protect.

But released smack bang in the middle of Britpop’s heyday, an era when anything outside the conventional meat and potato guitar band was viewed with the utmost suspicion, Raise The Pressure also appears to suffer something of an identity crisis.

“We were subconsciously aware of the attention we were getting as Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner, ‘formerly of’ The Smiths and New Order,” the latter admitted to website This Swirling Sphere in 1999. “We, in turn, paid too much attention to making the record and took too long doing it.”

That no doubt explains why the album is at times a little too overproduced and why instead of looking forward, it appears to be more comfortable glancing back. Indeed, For You, Out Of My League and One Day all mine the same kind of driving pop rock which had defined New Order’s Republic three years earlier.

While there’s little of The Smiths’ jingle-jangle, Marr’s riffs are a lot more prevalent, too.

Of course, sticking to what you know is hardly an ill-advised approach. Forbidden City, a poignant tale of a turbulent father-son relationship, is up there with the duo’s best. But rather aptly considering it arrived in the wake of Euro 96, it’s undoubtedly an album of two halves.

Twisted Tenderness (1999)

Electronic bookended the 90s with their third, and sadly final, album, a record which, despite the presence of pioneering electro producer Arthur Baker, veers further toward Marr’s wheelhouse than his partner in crime’s and yet there are still flashes of electronic brilliance.

Opening track Make It Happen is a seven-and-a-half-minute dancefloor epic which channels the thrilling big beat of The Chemical Brothers (who Sumner would work with later that same year) before drifting off into the night with a dreamlike acoustic outro.

The title track boasts an anthemic synth hook which recalls Felix’s club classic Don’t You Want Me. And alongside a scathing attack on an egomaniac who may or may not be a certain former bandmate (“You may be a star in your own mind but you’re greatly deluded in mine”), Prodigal Son initially evokes the claustrophobic dub of Massive Attack’s Mezzanine.

But elsewhere, and perhaps as a result of inviting Doves’ frontman Jimi Goodwin and Black Grape drummer Ged Lynch into the studio fold, Twisted Tendernessis more interested in rocking out. Bitter kiss-off Vivid (“Have you a reason to behave like this/ Maybe you need a psychoanalyst?”) is an infectious piece of post-Britpop which also allows Marr to showcase his skills on the harmonica.

The guitar hero also gets plenty of opportunities to do his more familiar thing on the squalling psych-rock of Breakdown and dynamic indie pop of Like No Other. And despite Sumner’s initial reservations (“I was a bit iffy about doing it,” he told This Swirling Sphere), the pair eventually accepted Baker’s idea of covering Blind Faith’s 1969 folk classic Can’t Find My Way Home.

However, the fact that a band who’d once prided themselves on marrying guitars and synths were now embracing such classicism perhaps justifies their decision in calling it a day. “As Bernard’s friend, I could see New Order needed to resume,” Marr later told Guitar.com, a selfless act which Sumner didn’t let go to waste. Apart from a 2006 retrospective and a one-off reunion performance of Getting Away With It at Jodrell Bank seven years later, Electronic have remained dormant ever since.

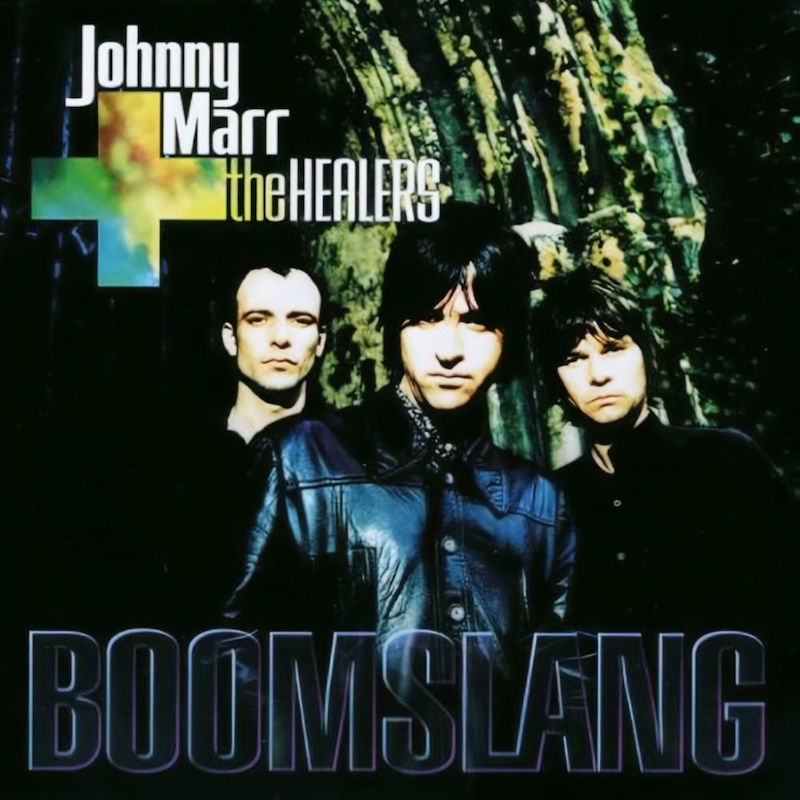

Boomslang (2003)

Having made his debut with The Smiths a full 20 years earlier, and with Morrissey about to launch his career-rejuvenating seventh solo effort, Marr decided it was about time he took the mic himself. Accompanied by The Healers, a band featuring the likes of future Oasis and The Who drummer Zak Starkey and Kula Shaker bassist Alonza Bevan, Boomslang proved that although Marr could undeniably hold a tune, his voice wasn’t quite yet distinctive enough to take centre stage.

Indeed, on the baggy funk of Down On The Corner, Marr closely resembles The Charlatans’ Tim Burgess, while perhaps inspired by his work on Oasis’ Heathen Chemistry, there are also echoes of Liam Gallagher’s swagger throughout.

Lyrically, however, things are unfortunately a little more Noel-esque, with Long Gone suggesting Marr relied on his rhyming dictionary a little too heavily (“I’m sinking like a stone/ Rolling in the foam/ Someone get me home!”)

The Eastern-tinged psychedelia of opener The Last Ride, Wild West rockabilly of Need It and scuzzed-up blues of InBetweens showed that Marr was still very much an undisputed guitar hero.

However, while no disgrace, Boomslang sounds like a supporting player cosplaying as leading man.

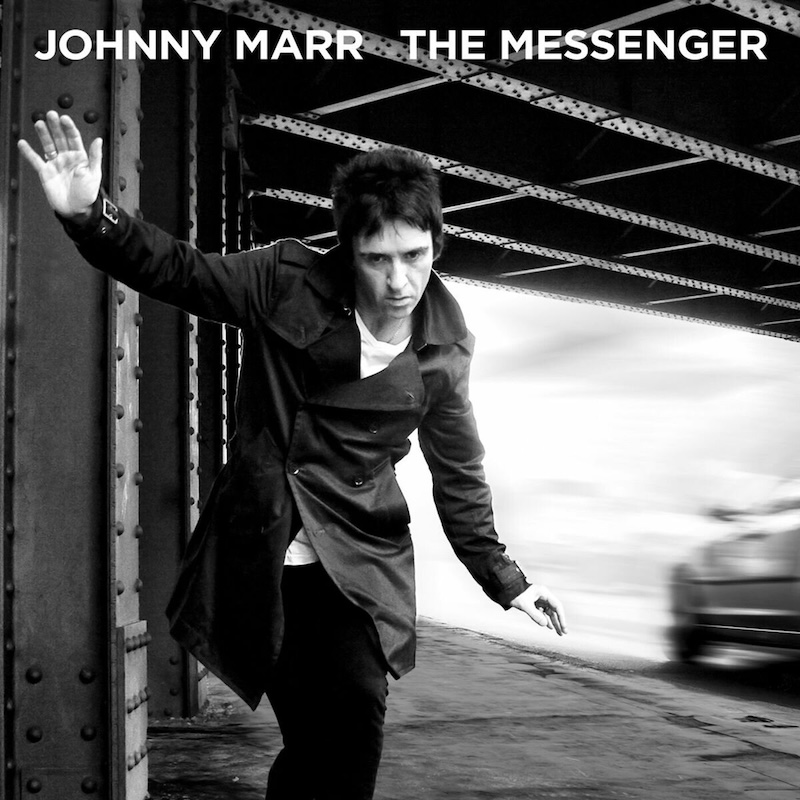

The Messenger (2013)

Following a decade of odd-jobbing including guesting on records by John Frusciante and Crowded House, working on the score for Christopher Nolan’s mindbender Inception and achieving his first ever US No.1 as a full-time member of Modest Mouse, Marr finally released his solo debut proper.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, The Messenger is heavily informed by his journeyman career. Lead single Upstarts is cut from the same primitive power pop cloth as The Cribs, the Yorkshire trio he briefly made a quartet. New Town Velocity could be mistaken for latter-day Electronic, with Marr’s somnambulistic vocal also sounding suspiciously like Sumner’s. Meanwhile European Me appears to borrow the Elvis-inspired riff from The Smiths’ Rusholme Ruffians.

There’s nothing here to match Marr’s career highs, but the stomping Northern Soul of opener The Right Thing Right and new wave pop of The Crack Up would merit a low-down placing on a Best Of. And although the guitarist may not be the most compelling lead singer, The Messenger proved he’d evolved as a lyricist, with I Want The Heartbeat satirising man’s over-reliance on technology and Generate! Generate! even serving up a Descartes-quoting pun that Moz would be proud of. File under inessential but promising.

Playland (2014)

“I always liked bands’ second albums,” Marr told Rolling Stone ahead of his 2014 own, citing Wire, Talking Heads and Buzzcocks as prime examples. Once again co-produced with James Doviak, Playland never comes close to reaching such heights, but as with all of Marr’s solo endeavours, it doesn’t detract from his legacy either.

In fact, lead single Easy Money, a funk punk anthem decrying societal greed, is one of the catchiest songs he’s ever put his name to.

Elsewhere, Dynamo is a suitably skyscraping burst of indie rock dedicated to Manchester’s CIS Tower, This Tension and the title track proves Marr still holds a torch for jangle pop and 70s glam respectively, while the propulsive Back In The Box and Little King are the sounds of a man making up for lost solo time.

The quick follow-up isn’t exactly the musical wonderland promised by its title – inspired by Dutch historian Johan Huizinga’s theory that playtime lies at the heart of modern civilisation. But what this album lacks in adventure, it makes up for in sheer unadulterated energy.

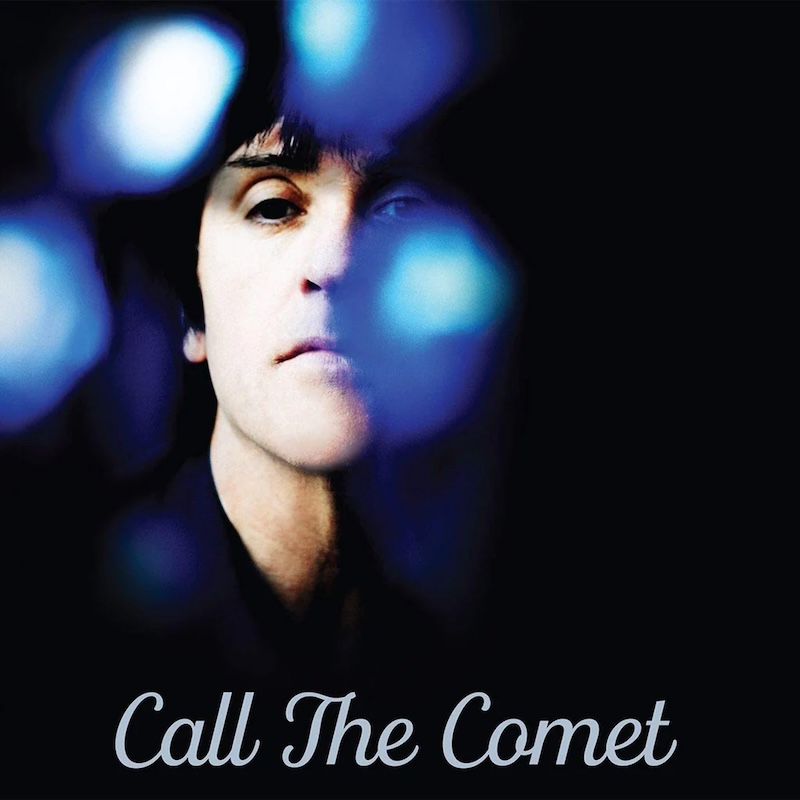

Call The Comet (2018)

“This time around, I had to imagine a society, rather than just report what I see,” Marr told the NME about third LP Call The Comet. Indeed, rather than reflect on the hellfire of Brexit and Trump’s rise to power that had occurred since his last solo venture, the guitarist decided the world desperately needed a major dose of positivity.

Marr’s utopian dream is perhaps best realised on Actor Attractor, a krautrock-inspired mission statement for the entire record (“Forever we can live to the limit”).

But The Tracers, a slice of gothic pop which could almost be mistaken for Sisters of Mercy, stadium rock-adjacent Spiral Cities and A Different Gun, the yearning closer written in the wake of the deadly Bastille Day attack in Nice two years earlier, all offer a similar sense of hope that things can get better.

Although there are still several nods to Marr’s past – Hi Hello borrows from both There Is A Light That Never Goes Out and Patti Smith’s Dancing Barefoot – Call The Comet is far more interested in looking forward musically, too, with the chiming New Romanticism of My Eternal and sombre post-rock of Walk Into The Sea majestic forays into fresh sonic territories.

For the first time, Marr’s solo career was now trumping Morrissey’s.

Fever Dreams Pts 1-4 (2022)

With his Glastonbury cameo alongside The Killers and contribution to Billie Eilish’s James Bond theme proving he was still very much revered by both millennials and Gen-Z alike, Marr approached his impending 60th birthday with his most ambitious project to date: a double album, and one which thanks to the small matter of a worldwide pandemic, recorded in solitary conditions, too.

Not that the Mancunian let events outside the studio inform his work too heavily. “I didn’t want to sing about face coverings and everything being closed,” he told Classic Pop about the making of Fever Dreams Pts 1-4, the first two of which were released as EPs. Although both Night And Day and Counter Clock World both appear to allude to the days of baking banana bread and Zoom quizzes, the majority of its 16 tracks look ahead to better times.

The Primal Scream-esque Tenement Time, for instance, is a rose-tinted lament to the guitarist’s teenage tearaway days (“I’m beating that street/ Running wild off the leash”), while Lightning People pays tribute to those who consider themselves a fully-fledged member of the Marr army.

On the surging post-punk of Receiver and brooding The Speed Of Love, the journeyman, who’s never exactly been renowned for his amorous nature, starts to aim his charms towards the bedroom.

Once again, Marr is in genre-hopping form, channelling Queens Of The Stone Age on the desert rock of Hideaway Girl, embracing his big screen work with Hans Zimmer on the ambient sci-fi soundscape of Rubicon and drawing things to a close with Human, a redemptive acoustic ballad which recalls 70s John Lennon.

The throbbing electro-rock of opener Spirit Power And Soul, meanwhile, is a strong candidate for his finest solo single. Of course, clocking in near the 75-minute mark, Fever Dreams doesn’t always sustain interest.

However, achieving Marr’s highest chart position since The Smiths’ first Best Of in 1992, its audaciousness undeniably paid off.

For more on Johnny Marr click here

Subscribe to Classic Pop magazine here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.