We take a deep dive into the legendary singer-songwriter’s diverse post-70s output

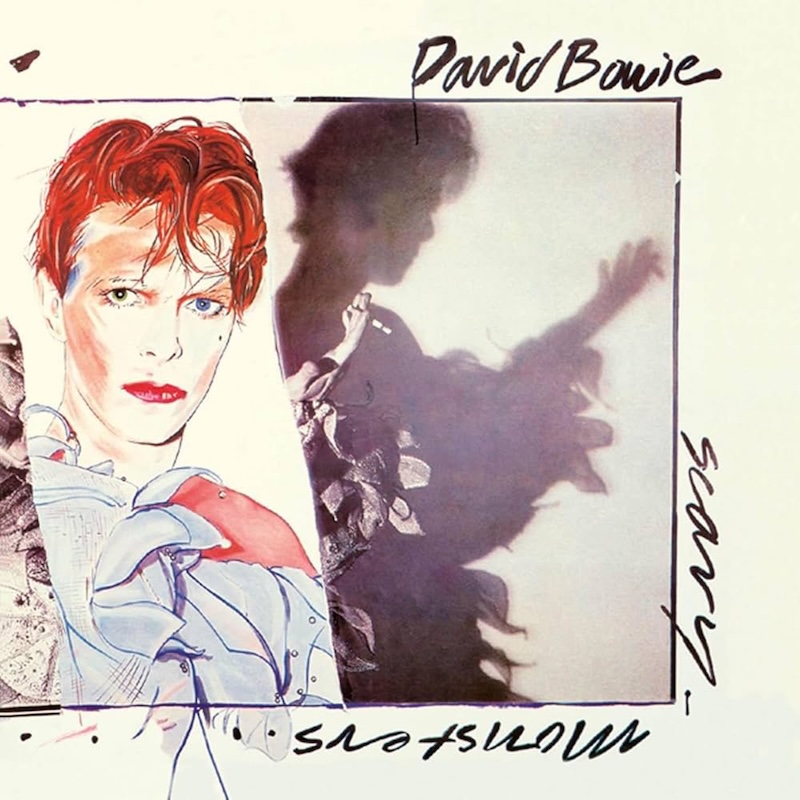

Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) (1980)

David Bowie’s first album of the 1980s was a milestone record for many reasons. It was his last to be co-produced with collaborator Tony Visconti for more than 20 years, his swansong for RCA and for many acolytes,

the final time that the star could be hailed as a true musical visionary.

Released just a year after wrapping up the Berlin trilogy that had seen him drift further towards the avant-garde, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) brought Bowie back to the mainstream, topping the UK charts and spawning only his second ever No.1 single.

With its self-mythologising nods to Space Oddity’s Major Tom, Ashes To Ashes certainly owes a thematic debt to his first hit single. But sonically it sounded poles apart, its chunky funk basslines and springy synths essentially shaping the sound of the decade ahead.

Meanwhile, its surrealist video – at the time the most expensive ever made – was similarly pioneering, an appearance from Visage’s Steve Strange giving the burgeoning New Romantic scene, (and the Bowie-worshipping Blitz club) one almighty seal of approval.

Also proving that Bowie still had his finger firmly on the pulse, the title track’s account of a woman descending into madness evoked the claustrophobic post-punk of Joy Division.

Kingdom Come, his first cover since Station To Station, helped to bring the art rock of Television frontman Tom Verlaine’s solo career to the masses.

Elsewhere, Fashion, both a celebration and mockery of society’s need to keep up with sartorial trends, channelled the mechanical new wave of Talking Heads.

Teenage Wildlife, the closest Bowie came to a “Heroes” sequel, suggests he wasn’t totally enamoured with every newcomer nipping at his heels, with the general interpretation being that it’s a riposte to his imitators, including man of the then-moment Gary Numan (“Same old thing in brand new drag comes sweeping into view/ As ugly as a teenage millionaire pretending it’s a whizz kid world”). Bowie also threw things back to the vintage rock’n’roll of Bo Diddley on Up The Hill Backwards while offering a rare insight into his break-up with first wife Angie. And the whole opus is bookended by songs titled It’s No Game, the first an abrasive blend of Japanese spoken word and intense guitars courtesy of Robert Fripp, the second a more sombre affair in which the narrator appears resigned to their fate.

As noted by Nicholas Pegg in The Complete David Bowie, Visconti claimed: “We kind of felt that we’d finally achieved our Sgt. Pepper” – a bold statement, but one that ultimately rang true.

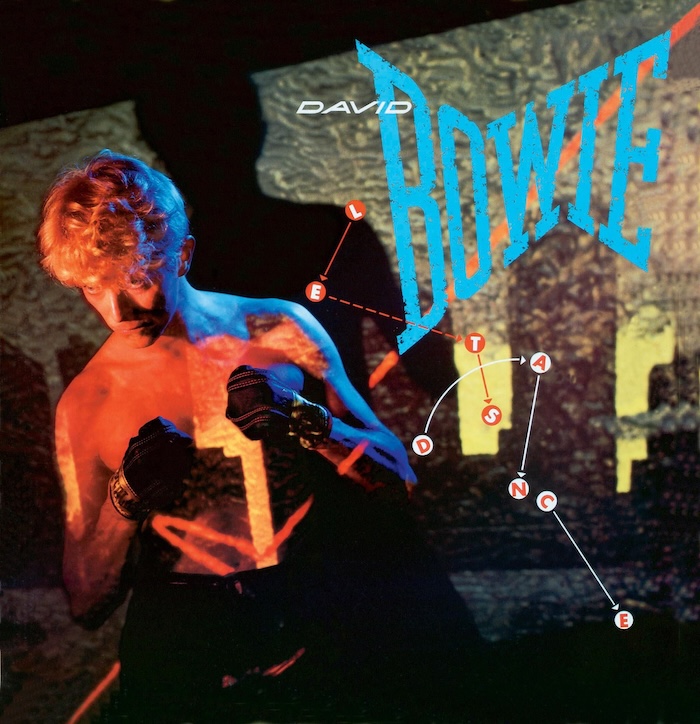

Let’s Dance (1983)

“I really want you to make hits.” That’s what Bowie told Rolling Stone magazine he requested from producer Nile Rodgers for his first album with EMI. With Let’s Dance spawning a No.1 7″ plus a duo of No.2 singles, picking up his first and only Album of the Year Grammy nod and shifting more than 10 million copies to become his all-time biggest seller, it’s fair to say the Chic founder fulfilled the brief.

Indeed, Rodgers’ fingerprints are all over the chart tour-de-force, from the Little Richard-inspired call-and-response of Modern Love to the title track, one of the 1980s’ finest No.1s which initially pays homage to The Beatles’ Twist And Shout before striding on to the dancefloor with some sublime New York funk.

Rodgers even manages to imbue the unrequited love tale of Iggy Pop’s China Girl, written and produced by Bowie for The Idiot, of course, with a playful disco-adjacent sheen.

Nicholas Pegg relays in The Complete David Bowie how Bowie would say, “It’s more Nile’s album than mine.”

While Let’s Dance is Bowie’s commercial peak, it does represent the start of his creative decline. The fact that three of its eight tunes are reworkings suggests that Bowie had yet to rediscover his musical mojo: he’d spent much of the last three years living as a recluse over fears of a John Lennon-style assassination, only occasionally resurfacing to pursue his acting career.

Bowie did, however, add at least one bona fide classic during this comparatively fallow period: the Giorgio Moroder-produced theme to erotic horror Cat People. Unwisely, however, he tinkered with the original a little too much here, turning what was a creeping bit of gothic rock into AOR.

Still, Bowie, who for the first time in his career decided against playing any instruments to focus entirely on his vocals, is always in fine form, whether it’s playing the crooner on the nostalgic pop of Without You or delivering just the right amount of swagger on the more experimental Ricochet.

Ultimately, Let’s Dance is a great mid-80s pop record, but only a good Bowie one.

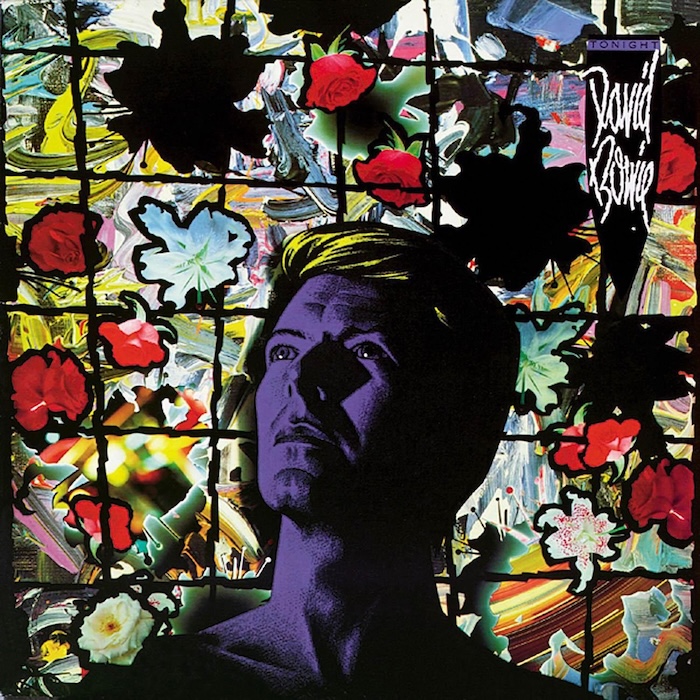

Tonight (1984)

Bowie appeared to go through something of an existential crisis during 1983’s Serious Moonlight Tour, the sea of new faces reeled in by Let’s Dance a perturbing presence for a man who’d previously always known his audience. That perhaps explains why he ditched ultimate hitmaker Rodgers for its follow-up Tonight, replacing him with the future producer of Phil Collins’ No Jacket Required.

To be fair, Hugh Padgham had only stepped in at the last minute following one too many creative disputes with original choice, Derek Bramble. And he later admitted that he’d felt too wet behind the ears to tell a bona fide rock god that his material wasn’t up to scratch. The music press, however, had no such qualms, with most outlets seeming to take great glee in giving a kicking to a man who had previously been untouchable.

Bowie himself proved to be just as dismissive. According to Nicholas Pegg in The Complete David Bowie, the singer later said, “It was just a collection of songs” that “sounded sort of jumbled; it didn’t hold together well at all.”

While Tonight undoubtedly has its fair share of problems – the awful version of The Beach Boys’ God Only Knows is a strong contender for an all-time career nadir, while no fewer than three perfunctory Iggy Pop covers (including a reggae reworking of Don’t Look Down) exemplify just how low the creative juices were flowing – it’s not a total write-off either.

The eerie sophistipop of opener Loving The Alien, one of the few tracks Bowie was happy to return to during subsequent tours, is arguably the standout.

Blue Jean is a rollicking throwback to the rock’n’roll of Eddie Cochran, and the rhythmic worldbeat of Tumble And Twirl, written with Iggy about their recent hedonistic escapades in Bali, is better use of his regular partner-in-crime’s musical talents.

But the title track collaboration with Tina Turner, is more representative of the record’s “this will do” approach. Indeed, there’s a strong sense that Tonight is more of a rush-release to capitalise on Bowie’s commercial rejuvenation than a necessary artistic statement.

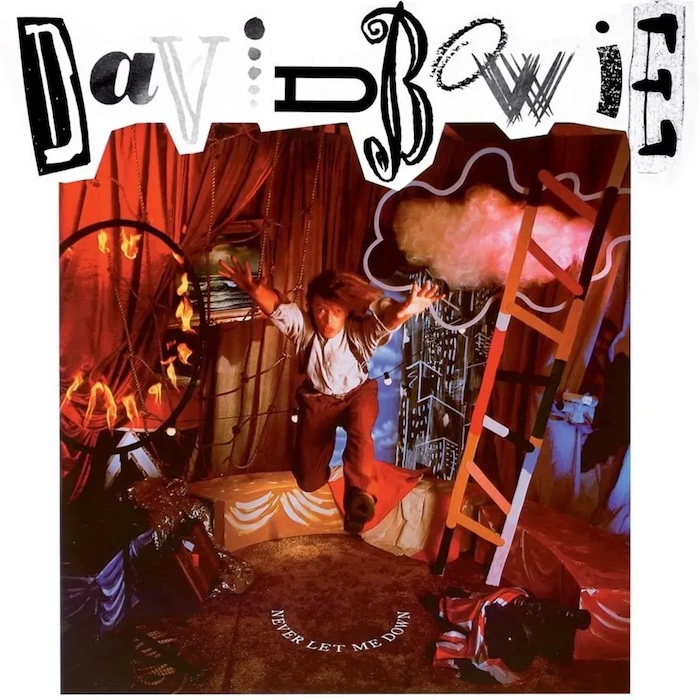

Never Let Me Down (1987)

The maligned Tonight is considered a masterpiece compared with its even more scorned follow-up, with Bowie arguably its harshest critic: “I really shouldn’t have even bothered going into the studio to record it,” he later admitted to Rolling Stone magazine. In fact, the star was so shameful about the 50s throwback Too Dizzy he later deleted it from all future pressings.

Following collaborations with Mick Jagger and the Pat Metheny Group, Bowie continued to widen his circle, inviting his old mate Peter Frampton to play lead guitar and, bizarrely, actor Mickey Rourke to rap on the falsetto-led survival tale Shining Star (Makin’ My Love).

Yet Bowie remained heavily in thrall to Iggy Pop, tapping up David Richards, the producer who’d just worked on his Blah-Blah-Blah album, and covering his 1981 hit Bang Bang. The continued over-reliance on drum machines and rudimentary synths means it’s dated just as badly, too.

It isn’t entirely without merit. The title track is a lovely Lennon-esque dedication to his personal assistant Coco Schwab and would be Bowie’s last US Top 40 hit for nearly 30 years.

Commentaries on Los Angeles’ homelessness problem (Day-In Day-Out) and Thatcherite Britain (87 And Cry), meanwhile, proved that Bowie still had a potent way with words.

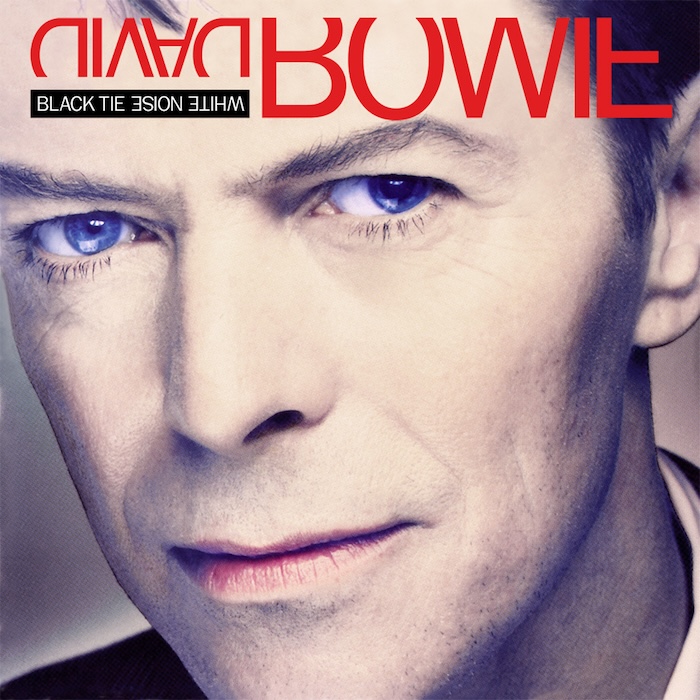

Black Tie White Noise (1993)

Following two unloved hard rock albums with side project Tin Machine, Bowie essentially hit the reset button with his first solo LP in six years, and arguably his first passable in 10. Inspired by both his marriage to supermodel Iman and the Los Angeles riots that occurred five days later, Black Tie White Noise is, unsurprisingly, a record of two halves.

It opens with The Wedding, a sensuous blend of trip-hop beats, Middle Eastern woodwind and church bells that Bowie composed specifically for his nuptials, and closes with a vocal reprise in which he describes his bride as an “angel for life.”

He also plays the romantic on Miracle Goodnight, a crooning rendition of Morrissey’s I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday and Don’t Let Me Down & Down, an English-language reworking of an obscure ballad from Mauritanian singer Tahra Mint Hembara.

Among all the unabashed expressions of love, however, Bowie also addresses much darker issues. The title track, an unlikely duet with new jack swing favourite Al B. Sure!, holds a mirror up to both white privilege (“Getting my facts from a Benetton ad”) and the beating of Rodney King.

Meanwhile, he also tackles the tragic suicide of his schizophrenic half-brother Terry Burns on the paranoid funk of Jump They Say, his first Top 10 hit since Absolute Beginners seven years earlier.

Also featuring covers of Cream’s I Feel Free and The Walker Brothers’ Nite Flights – the former boasting old cohort Mick Ronson – a Tin Machine outtake (You’ve Been Around) as well as a jazz instrumental (Looking For Lester) which allowed Bowie to show off his sax skills, Black Tie… kickstarted an experimental period in which the star’s critical reputation gradually recovered.

Although consciously rallying against the idea of making Let’s Dance Part II, Bowie’s reunion with Nile Rodgers sparked a similar renaissance. Indeed, not only did Bowie start rubbing shoulders with Brett Anderson on the front cover of the NME, he also coincidentally replaced Suede’s self-titled debut at the top spot of the UK Albums Chart, too.

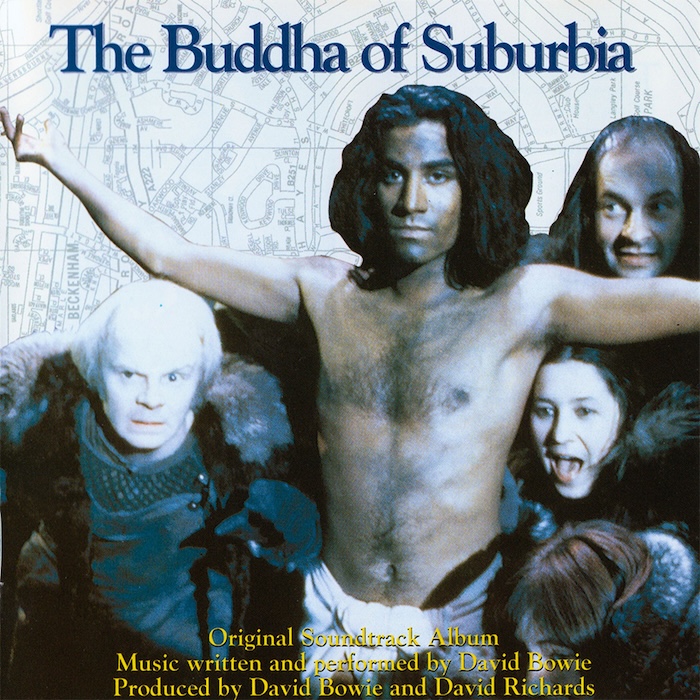

The Buddha Of Suburbia (1993)

The Buddha Of Suburbia was conceived to soundtrack the 1993 BBC four-part adaptation of Hanif Kureishi’s 1990 novel. However, only the title track made it into the television drama and, following a distinct lack of promotion or marketing, it bellyflopped in the UK charts at No.87 before being consigned to the vaults. US fans couldn’t even get their hands on it until two years later.

Bowie’s curious claim in 2003 that the record is his personal favourite suggests he was not the most reliable assessor of his own work.

But while the 10-track affair is far from top-tier David, there are still several lesser-known gems. Sex And The Church is a pulsating electro-funk number which harnessed the joys of the vocoder several years before Cher. Strangers When We Meet is far superior to the reworking that later appeared on Outside, while Bleed Like A Craze, Dad, a collaboration with little-known trio 3D Echo, is a slinky throwback to the white boy funk of Fame.

Ambient instrumental Ian Fish, U.K. Heir – an anagram of Kureishi’s name, in case you were wondering – spends more than six minutes aimlessly wandering in search of a melody, and Lenny Kravitz fails to make his presence heard on an alternative cut of the eponymous opener.

More intriguing stopgap than an underappreciated hidden treasure.

Outside (1995)

Never one for following the crowd, Bowie decided the most obvious plan of action during the height of Cool Britannia was to release an industrial rock concept album about the murder of a teenage girl which sat somewhere between Nine Inch Nails and Twin Peaks. In fact, David Lynch’s cult classic appears positively straightforward compared to the non-linear narrative that stretches across a highly challenging 75 minutes.

Indeed, good luck making any sense of the story set between 1977 and 1999 in the fictional New Jersey setting of Oxford Town, one populated by characters including a hardened detective, 70-something loner and shadowy entity named the Minotaur. Even the multiple spoken word interludes and CD booklet’s diary entries fail to make things much clearer. “There’s too much on it,” Bowie acknowledged to Los Angeles journalist Mark Brown in 1997, referring to a record that also spawned a comic book series and a three-hour bootleg.

Reuniting with Brian Eno for the first time since the Berlin trilogy, Outside’s sound is no less unorthodox, whether the squalling cabaret jazz leanings of A Small Plot Of Land, the avant-garde minimalism of Wishful Beginnings or the pummelling sci-fi rock of Hallo Spaceboy, almost unrecognisable from the Pet Shop Boys-assisted remix that made the UK Top 20 the following year.

While most of Outside wilfully defies the concept of an easy listen, it does contain at least one immediate gem in the shape of The Hearts Filthy Lesson, a muscular slab of cyber-rock that appeared in the end credits of David Fincher’s 1995 film Seven and whose gruesome MTV-banned video proved that Bowie still possessed the power to shock. Meanwhile, We Prick You and I’m Deranged, the latter of which neatly brought things full circle as the bookending theme to Lynch’s headscratcher Lost Highway, cleverly teased the drum ’n’ bass direction that would define its successor.

Outside is unlikely to top any Bowie fan’s all-time list but it remains an admirably audacious, if self-indulgent, affair.

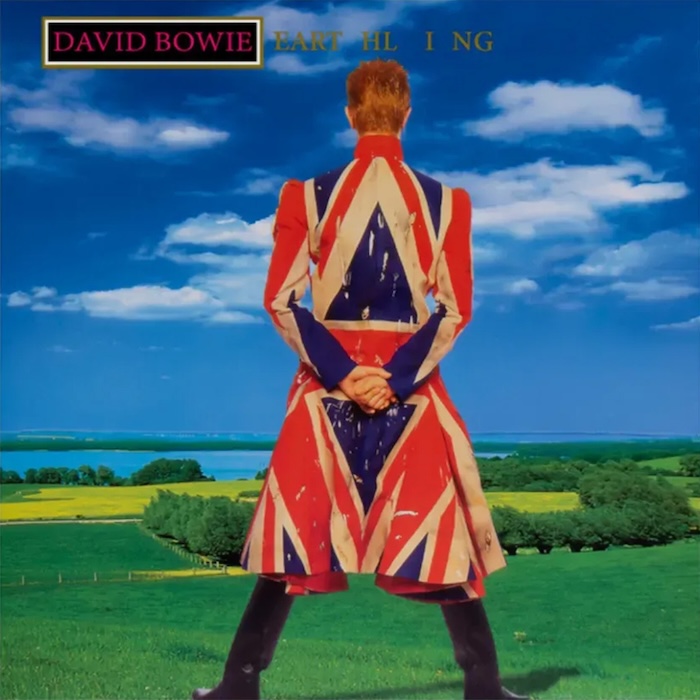

Earthling (1997)

“I thought that what we should do was develop our vocabulary of dance forms, but incorporate rock,” Bowie explained to Live magazine about what became known, often in a derogatory manner, as his drum ’n’ bass album. Earthling may have been released a few years too late to be considered pioneering but considering Roni Size’s New Forms won the Mercury Prize a few months later, it is hardly the out-of-step affair some of its critics purported.

Only a handful of tracks fully commit to the breakneck speed genre. Single Little Wonder is the most convincing, combining bizarre stream-of-consciousness lyrics inspired by the Seven Dwarves (“Dopey morning Doc, grumpy gnomes”) with thrilling stop-start beats and shrieking guitars. But Telling Lies, which as the first official download-only single further bolstered Bowie’s reputation as a technological soothsayer, also subscribe to the “jungle is massive” ethos with aplomb.

Likewise, Battle For Britain (The Letter) in which the star questions his identity (“And a loser I will be for I’ve never been a winner in my life”) before being interrupted by a piano solo inspired by Stravinsky.

Elsewhere, Seven Years In Tibet picks up where the industrial rock of Outside left off. Having cited The Prodigy’s Music For The Jilted Generation as an all-time pet sound, Bowie echoes its thunderous techno-rock on Dead Man Walking (initially a tribute to Susan Sarandon would you believe?).

Continuing the unlikely origin stories, I’m Afraid Of Americans began life as a Showgirls soundtrack cut named Dummy before being repurposed into a crunching and ever-timely critique of Uncle Sam. Time has certainly been much kinder to its full-throttle sound, certainly compared to the dying days of the Britpop scene.

Although he sported an Alexander McQueen-designed Union Jack suit jacket for its cover art, the forward-thinking Earthling – as with its predecessor – once again proved that Bowie had very little interest in fetishising the past.

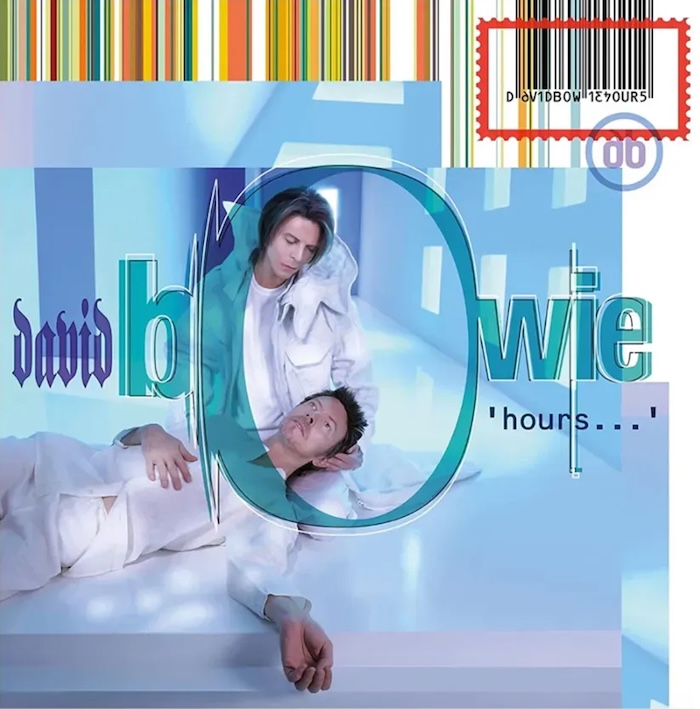

Hours (1999)

While his earlier 90s records appeared to be dripping in pre-millennial tension, Bowie’s final album before the dreaded Y2K was a far more meditative affair, where the only angst on show concerned the inevitability of ageing.

Opening lead single Thursday’s Child is a beautifully melancholic declaration of love, perfectly set the tone ahead. Indeed, the pace only really picks up on Stooges-esque glam of The Pretty Things Are Going To Hell and the tempo-shifting closer, The Dreamers, which centres on a traveller wondering whether his best days are behind him.

If I’m Dreaming My Life is a seven-minute sleepwalk through the breakdown of a relationship, and the eerie rocker What’s Really Happening, co-penned by a BowieNet songwriting competition winner, chugs along in search of an answer.

Brilliant Adventure is a koto-led instrumental which sounds more suited to a day spa than the wild ride promised by its title.

Intriguingly, Hours, which was released online several weeks before hitting shelves, was initially devised as a soundtrack to Omikron: The Nomad Soul, a video game combining the supernatural with a murder-mystery. It’s an odd fit for a record which, although tasteful and timeless, offers few thrills or surprises.

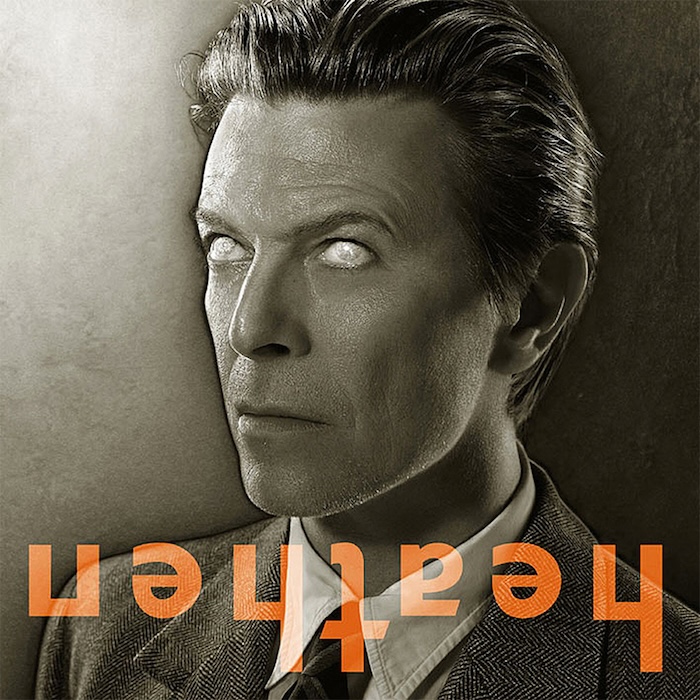

Heathen (2002)

“The circumstances, the environment, everything about it was just perfect for us to find out if we still had a chemistry that was really effective,” Bowie remarked to Richard Buskin (Sound On Sound), when reflecting on working with Tony Visconti for the first time since 1980. It was a reunion which also birthed arguably the star’s most well-received album since they ended their fruitful partnership.

Released through his own ISO Records label, Heathen saw Bowie bag nominations at the Mercury Prize and Grammy Awards (the latter for Slow Burn featuring Pete Townshend) while also achieving his highest charting position in the States for 18 years.

Clearly, after two decades of experimenting with varying degrees of success, the wider world had been waiting for the musical chameleon to get relatively back to basics.

Indeed, only the skittering drum ’n’ bass of I Would Be Your Slave and pulsing techno-rock of The Legendary Stardust Cowboy’s I Took A Trip On A Gemini Spaceship, the sci-fi tale Bowie freely admits he pilfered for his Ziggy Stardust days, really places the record in the modern day. The man himself appears to acknowledge the time warp factor, singing “Down in space, it’s always 1982” on Slip Away, a Space Oddity-esque ballad bizarrely inspired by the puppetry of kids cult favourite The Uncle Floyd Show.

There are further nods to his classic back catalogue on lead single Everyone Says ‘Hi’, a jaunty tribute to departed guitarist Reeves Gabrels which could have easily slotted onto Hunky Dory, the Berlin-era new wave of Afraid and I’ve Been Waiting For You, the Neil Young cover which was a staple of Tin Machine’s early 90s setlists.

Having become a new dad at 53 and having recently lost his mother, Margaret, Bowie is in a far more reflective mode on Heathen. A Better Future pleads with a higher power to make the world much less of a hellfire (“Give my children sunny smiles/ Give them moon and cloudless skies”).

“I wouldn’t change a note of it,” he declared per The Complete David Bowie, about a record that proved he was finding a new middle-age groove.

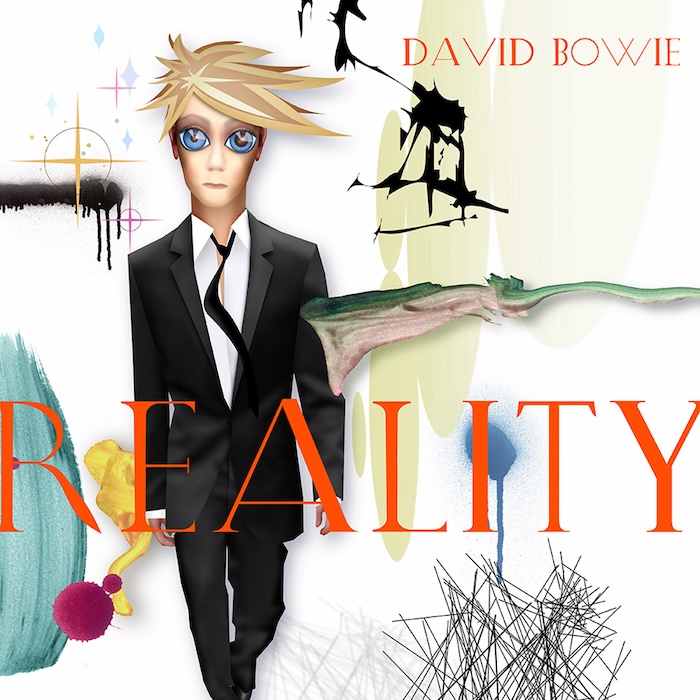

Reality (2003)

Continuing the themes of ageing, mortality and post-millennial angst, Bowie’s 24th album ambitiously tried to deconstruct the concept of reality: hence the abstract artwork which presents the full-bodied star in 2D anime.

She’ll Drive The Big Car, bonus disc track Fly and near a cappella The Loneliest Guy all depict characters worn down by the hardships of everyday life.

The curiously named anti-war anthem Fall Dog Bombs The Moon serves up a blistering attack on Dick Cheney. And while Bowie had refuted claims that Heathen was heavily inspired by 9/11, opener New Killer Star appears to clearly reference the tragedy that unfolded a mile from his Big Apple home (“See the great white scar/ Over Battery Park”).

Although its lyrical themes are steeped in melancholy, the returning Visconti’s production is positively buoyant and the title track is the hardest Bowie had rocked since Tin Machine. Meanwhile, closer Bring Me The Disco King is an eight-minute musical odyssey which delves into his love of New York jazz.

Reality proved once again this is David Bowie’s world and we’re all just living in it.

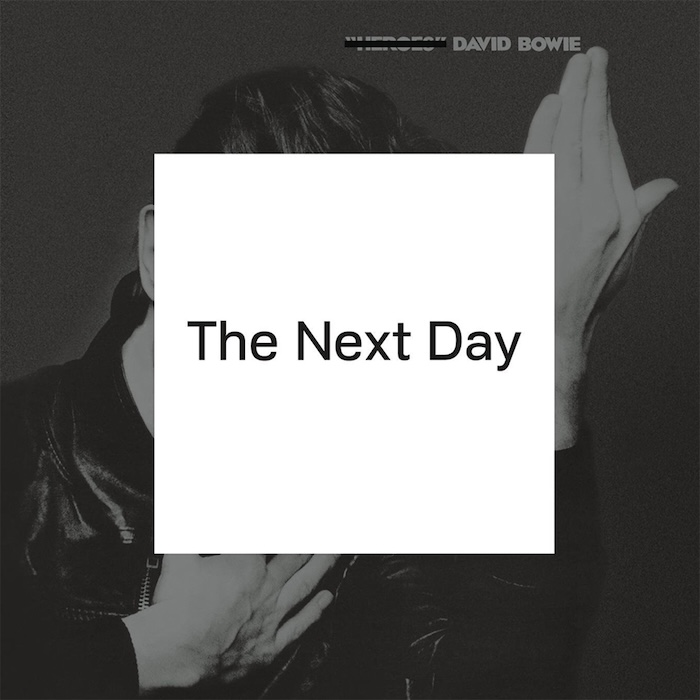

The Next Day (2013)

Apart from the odd guest appearance (TV On The Radio, Scarlett Johansson), Bowie’s music career had lay dormant since a health scare forced him to cancel the A Reality Tour in 2004.

So, his unannounced comeback nine years later was inevitably met with a mixture of shock, awe and uncertainty about whether he was set to extend his legacy or tarnish it. Thankfully, it proved to be the former.

The Next Day essentially picked up where his Noughties output had left off.

The Stars (Are Out Tonight), a propulsive alt-rock number which imagines A-listers as cannibalistic aliens, and the broken beats of If You Can See Me, for example, both proved Bowie hadn’t lost his ability to stay on trend. However, nods to former partners in crime Iggy Pop (Dirty Boys) and Lou Reed (Valentine’s Day), the Ziggy Stardust-referencing torch song You Feel So Lonely You Could Die and The Shadows-interpolating post-war tale How Does The Grass Grow? all brilliantly filtered his musical heritage through Visconti’s contemporary sheen.

A twilight-years classic which deservedly returned Bowie to the upper reaches of the charts.

Blackstar (2016)

After the release of The Next Day, Bowie once again caught everyone off guard when he released the entirety of his 26th album Blackstar without any prior warning. Of course, that was nothing compared to the shocking news just two days later of his untimely death.

Inevitably, fans quickly began reassessing its lyrical content, poring over each line for anything which hinted the end was near. “Look up here, I’m in heaven,” from Lazarus, the soporific piece of chamber pop which had just graced the same-named off-Broadway musical, was an obvious example.

Yet Bowie’s studio swansong, which became his first Billboard chart-topper, has far more to offer than its slightly morbid treasure hunt.

Whereas its predecessor was happy to rely on the tried and tested, Blackstar was determined to push things forward. “Avoid rock’n’roll” was essentially the mantra of an album which delved deep into the star’s longtime passion for jazz and explored his love for thought-provoking hip-hop.

This experimental approach instantly reaps its rewards with the opening title track, an audacious fusion of ambient R&B and freeform jazz which at over 10 minutes is second only to Station To Station as Bowie’s longest. Few other artists could get away with releasing such a deliberately uncommercial jam as a lead single.

’Tis A Pity She Was A Whore and Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime), both derived from 2014 retrospective Nothing Has Changed, are given beefier upgrades. The ominous funk of Girl Loves Me incorporates the queer slang known as Polari and the Nadsat register devised for A Clockwork Orange alongside the repeated query of “Where the fuck did Monday go?” And closer I Can’t Give Everything Away shows how he remained wonderfully contradictory (“Seeing more and feeling less/ Saying no but meaning yes”) right to the end.

A final glorious reinvention from the most chameleonic man ever to grace the world of pop.

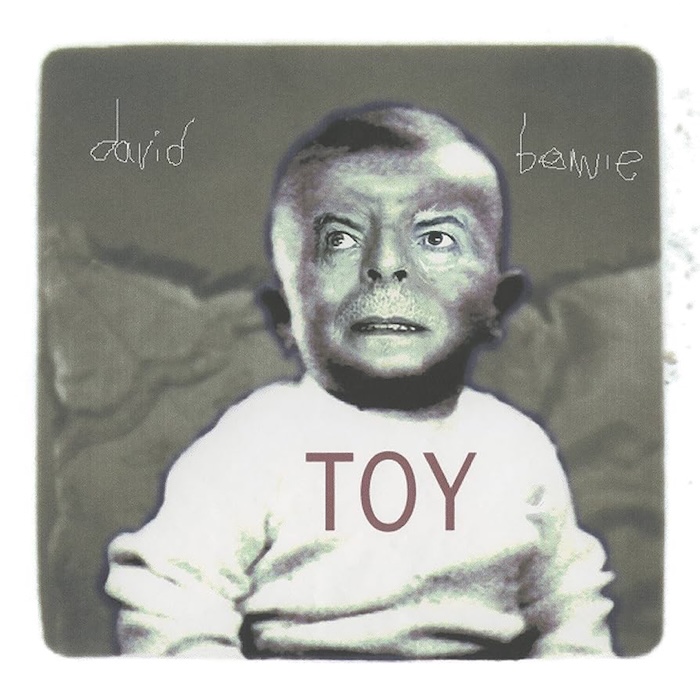

Toy (2021)

I cannot wait to sit in a claustrophobic space with seven other energetic people and sing till my tits drop off,” Bowie wrote in a tour diary for Time Out in 2000, about the Toy sessions booked following his triumphant performance at that year’s Glastonbury. It’s fair to say his record label wasn’t as enthused by a re-recorded collection of songs which largely stemmed from the period when he was better known as Davy Jones.

While the star had hoped to surprise drop a new throwback album the following spring, EMI/Virgin had other ideas, continually pushing back its release date before scrapping it altogether.

Keen to salvage the material, however, Bowie later repurposed several reworkings for Heathen.

The album was released in November 2021, in the boxset Brilliant Adventure (1992-2001), as well as an expanded 3CD release titled Toy:Box on the eve of what would have been his 75th birthday.

So was Toy worth all the hassle? Well, for Bowie’s loyal fanbase, yes. Having been left in the vaults since being dropped from The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust, the resurfacing of Shadow Man is something of a holy grail. There’s also a curiosity factor to his new takes on You’ve Got A Habit Of Leaving and Can’t Help Thinking About Me. But for casual fans, it is little more than a sidenote.

For more on David Bowie click here

Read More: Top 20 Swansong Singles

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.