Talking Heads revolutionised rock by fusing art-school sensibilities with punk energy, funk rhythms, and avant-garde innovation across the albums covered here

Emerging from New York’s thriving punk scene in the late 70s, Talking Heads soon distanced themselves from the CBGB crowd with an energetic and highly idiosyncratic mix of afrobeat, avant-funk and artpop which broadened rock’s perimeters.

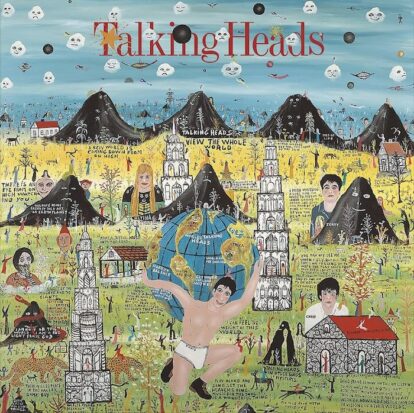

Talking Heads: 77 (1977)

Having formed in 1975, Talking Heads surfaced from the ashes of New York band The Artistics, with frontman David Byrne and drummer Chris Frantz eventually recruiting (after three auditions) fledgling bassist Tina Weymouth and former The Modern Lovers keyboardist Jerry Harrison to a line-up that, unusually, would remain unchanged throughout their 16-year existence.

Drawing upon their originators’ Rhode Island School of Design background – and for their name – a term featured in a random copy of TV Guide, the band quickly garnered a buzz on the Big Apple circuit, particularly the CBGB club they’d made their live debut at. And following false starts with Sire Records’ head honcho Seymour Stein and early mentor Lou Reed (whose main advice was for Byrne to hide his hairy arms on stage), the quartet finally headed into the studio to record their first album with producers Tony Bongiovi and Lance Quinn. Well, kinda.

The former, a cousin of future hair metal god Jon Bon Jovi, immediately rubbed the band up the wrong way with his repetitive and uncaring approach, with Frantz later claiming that engineer Ed Stasium deserved far more of the credit. Whoever was responsible for producing its twitchy, tight-knit sound, Talking Heads: 77 immediately positioned its performers as an angular alternative to their riotous punk peers. While Ramones thrived on simplicity, their one-time support act were more concerned with pushing musical boundaries and as their own mission statement revealed, offering “sincerity, honesty, intensity, substance, integrity and fun.”

The calypso funk of opener Uh-Oh, Love Comes To Town proved right off the bat that Talking Heads weren’t interested in adhering to guitar band traditions. Likewise, the conga-friendly coda of Tentative Decisions, the marimba-meets-saxophone stylings of First Week/Last Week… Carefree and new wave disco of The Book I Read.

The rock scene certainly hadn’t heard anyone quite like Byrne, either. Don’t Worry About The Government, a sardonic tribute to the work of civil servants, and unempathetic No Compassion (“So many people have their problems/ I’m not interested in their problems”), for example, both allowed the sharp-suited frontman to exhibit his otherworldliness, his stilted delivery and peculiar takes on modern society suggesting he’d just been beamed to Earth from another planet.

Of course, most fans’ first introduction to Talking Heads was Psycho Killer, the instant classic which amid the Summer of Sam, dared to inhabit the mind of a knife-wielding murderer. Initially conceived as Alice Cooper singing a Randy Newman ballad, the macabre tale might have caused a minor controversy, but its surprise Billboard Hot 100 success suggested the punk crowd were willing to embrace something outside the norm.

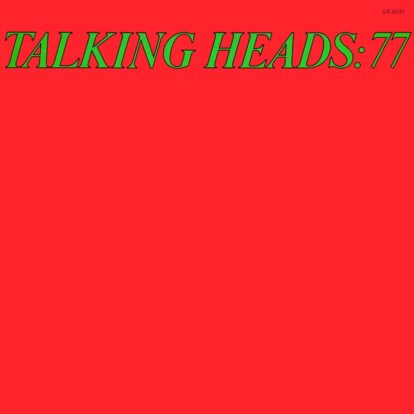

More Songs About Buildings And Food (1978)

The self-deprecating title of Talking Heads’ second album suggested more of the same. But it proved a milestone record, kickstarting a fruitful association with both Brian Eno – the producer who’d become transfixed by the group after watching their Ramones slot – and Bahamas’ famous Compass Point Studios.

It also spawned the band’s first US Top 30 hit, a new wave take on Al Green’s soul standard, Take Me To The River, and in pushing the newly-married Weymouth and Frantz to the forefront, helped redefine their rhythmic sound.

Stay Hungry, for instance is a funky instructional workout for the bedroom no doubt inspired by the James Brown tapes that soundtracked their previous tour bus journeys.

Meanwhile, the galloping tribal beats of opener Thank You For Sending Me An Angel indicate how Eno turned the band onto the joys of Fela Kuti.

Of course, Byrne is still the star of the show, whether it’s chastising the opposite sex for their interest in abstract analysis on the garage rock of The Girls Want To Be With The Girls, indulging in corporate lingo on the gradually escalating The Good Thing (“As we economise, efficiency is multiplied”) or awkwardly delivering come-ons such as “take it easy baby” on Warning Sign. Byrne is many things, but a natural ladies man he is not.

More Songs About Buildings And Food also defies its ‘leftover’ status with several meditations on love – a subject the band had largely ignored – from the warring married couple who use their screenwriting skills to iron out their problems on Found A Job to I’m Not In Love, not a 10cc cover but an energetic throwback to their punk roots which argues that it’s simply a needless social construct.

But it’s the skewering of middle America which provides the album’s benchmark. “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me/ I wouldn’t live like that, no siree,” Byrne insists on The Big Country, a Nashville-tinged affair which ends the record on a swoonsome yet still proudly sardonic note. More Songs… may have pushed Talking Heads a little closer to the mainstream, yet the quartet still appeared determined to cling on to its fringes.

Fear Of Music (1979)

“We don’t want to compromise for the sake of popularity,” Byrne noted to Rolling Stone about Talking Heads’ third LP. Considering Fear Of Music contains a protest against carbon dioxide inspired by Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera (Air), a woozy piece of psychedelic ambience including the sound of croaking frogs (Drugs) and an Afrodisco anthem based on a nonsensical Hugo Ball poem (I Zimbra), it’s fair to say mission complete.

Inspired by returning producer Eno’s unique approach to writer’s block – creating a table of thematic contents – the album’s titles may be unusually bland. But its sound is anything but, allowing Byrne’s “insane but fantastic” sense of rhythm to run wild on 11 idiosyncratic tracks, many of which were recorded in Frantz and Weymouth’s New York loft.

Born out of a jam session, the sublime Life During Wartime, for example, boasts the kind of dancefloor-friendly beats that wouldn’t sound out of place at Studio 54, slightly contradicting Byrne’s insistence “this ain’t no disco.” The irony continues on Memories Can’t Wait, a clanging no-wave nightmare in which the line, “There’s a party in my mind, and I hope it never stops” amounts to self-flagellation.

Fear Of Music’s lyrical themes are just as wonderfully avant-garde. Animals is essentially an anti-PETA ad in frantic indie-rock form, with Byrne hilariously arguing that any creatures existing solely on nuts and berries are of little use to humanity (“They don’t even know what a joke is”).

While the band’s first two albums grounded their character studies in reality, here they are launched into various desperate, dystopian situations, whether surviving on peanut butter in a post-apocalyptic future or embarking on a fruitless chase for the perfect urban settlement.

But like its predecessor, Fear Of Music’s highlight arrives courtesy of its simplest moment. Heaven was apparently inspired by London’s same-named gay bar, yet there’s little hedonistic about its stark arrangement and realisation that the next world is a highly repetitive “place where nothing ever happens.” Come for the Dadaist chants, stay for the spiritual enlightenment.

Remain In Light (1980)

After working on side project My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, Byrne – along with the rest of an unsettled Talking Heads – reunited with Eno for what would be the last time. Remain In Light saw the former Roxy Music man stamp his mark harder than ever before, turning the quartet onto the polyrhythms of African music and encouraging them to see the brighter side of life: “What a fantastic place we live in,” was the main ethos as he told NPR. “Let’s celebrate it.”

Perhaps affected by the intra-band tensions – both Weymouth and Frantz had considered leaving due to Byrne’s unwillingness to relinquish creative control – the record didn’t always hit such an optimistic tone.

Amid the staccato guitars and cowbells of Crosseyed And Painless, a ranting Byrne inhabits the mind of a lost soul seemingly perturbed by the age of disinformation (“Facts just twist the truth around/ Facts are living turned inside out”).

Meanwhile, the ominous dub of Listening Wind centres on a third world lone terrorist planning to avenge American colonialists with a mail bomb.

But it’s clear that the group listened to Eno’s musical advice, continually absorbing the influences he helpfully listed in a bibliography handed out to the press and giving them a New York spin. From the percussive paranoia of opener Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On) to the slow-motion industrial of post-apocalyptic closer The Overload, Remain In Light pushed American rock into places it previously hadn’t dared to venture towards. And implored you to dance while doing so.

Of course, the band did manage to get both funky and free-spirited on their breakthrough UK single. Accompanied by a memorable Toni Basil-directed video which turned the jittery Byrne into an unlikely MTV star, Once In A Lifetime is a whirlwind of Hammond organs, spiralling synths and loping grooves delivered in the manner of a life-affirming sermon. It’s the pièce de resistance of a record which left many hailing the Heads as godlike geniuses.

The Name Of This Band Is Talking Heads (1982)

Viewed as the forgotten live album, The Name Of This Band Is Talking Heads captures the quartet in their element across four discs of radio and stage performances. And by spanning the eventful early years of their inception, it highlights just how quickly their sound evolved.

Recorded at Massachusetts’ Northern Studio for station WCOZ in 1977, Side One also proves immediately that while Byrne was a natural showman, his onstage patter left a lot to be desired. “The name of this song is New Feeling, that’s what it’s about,” he introduces the first of four numbers from their self-titled debut, almost trolling listeners with the lack of further context.

Still, the double LP does placate hardcore fans elsewhere with the first official release of A Clean Break (Let’s Work), a vibrant amalgamation of everything that made their arrival such a breath of fresh air. It’s a mystery as to why the group never committed it to a studio effort.

The remaining dozen tracks are taken from three different occasions; headline gigs at the Capitol Theater in 1979 and Emerald City in 1980 – two historic New Jersey venues which, like the Heads themselves, are sadly now defunct – and a show-stealing slot at the Dr. Pepper Central Park Music Festival in New York.

Having added the likes of future King Crimson guitarist Adrian Belew, journeyman bassist Busta ‘Cherry’ Jones and Parliament-Funkadelic keyboardist Bernie Worrell to their live set-up, it’s here where the Heads truly come into their own as a must-see act, with highlights including the single Love ’ Building On Fire, and a propulsive Crosseyed And Painless, arguably the definitive take.

Of course, considering what followed just two years later, The Name Of This Band… was soon dismissed as surplus to requirements: it didn’t even get a CD transfer until 2004. But it remains an intriguing snapshot of a group clearly on the rise to greatness.

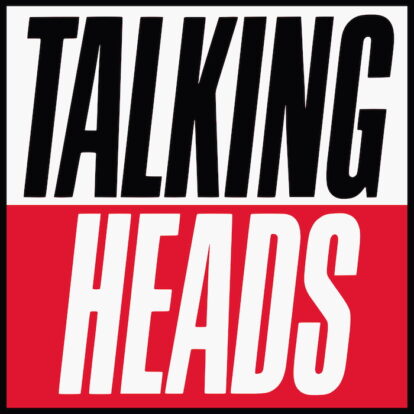

Speaking In Tongues (1983)

After four albums in quick succession, Talking Heads made fans wait three years for the self-produced Speaking In Tongues. Not that they’d been idle in the meantime, with Weymouth and Frantz forming new wave duo Tom Tom Club, Harrison releasing solo album The Red And The Black and Byrne penning the score for ballerina girlfriend Twyla Tharp’s acclaimed dance project The Catherine Wheel.

It’s fair to say that the quartet came back in a blaze of glory, literally in the case of lead single Burning Down The House, a fiery, Funkadelic-indebted jam which later helped to spearhead Tom Jones’ career renaissance in the late 90s. It remains their only US Top 10 hit.

And there were plenty more idiosyncratic gems on what also remains the Heads’ highest charting album Stateside, from the John Lee Hooker-esque delta blues of Swamp and the frazzled disco of Pull Up The Roots to the skank reggae of I Get Wild/Wild Gravity and the call-and-response gospel of Slippery People, the latter introducing former Labelle singer Nona Hendryx into the regular backing vocal fold.

But the quartet undoubtedly saved the best for last. “I tried to write one that wasn’t corny, that didn’t sound stupid or lame the way many do,” Byrne explained about closing serenade This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody) during a DVD interview for Stop Making Sense. And he sure succeeded on possibly the first Heads song to address the affairs of the heart without any layers of irony. Its arsenal of non-sequiturs might not paint the clearest of romantic pictures, but it is plainly evident that pop’s most abstract frontman has succumbed to the fully formed concept of love.

“We have nothing in our pockets/ We continue/ But we have nothing left to offer,” Byrne claims amid the shimmering synths and funk beats of Making Flippy Floppy.

Speaking In Tongues, whose subsequent tour would produce arguably the greatest concert film of all time, proved that was far from the case.

Stop Making Sense (1984)

“We took great joy in what we were playing on stage and our interactions with each other,” Jerry Harrison told NPR about arguably the Heads’ defining pop culture moment. “But we really wanted the audience to come away and go, ‘That was one of the best things I ever saw’ — like, every night.” It’s fair to say they got their wish.

Indeed, directed by future Academy Award winner Jonathan Demme, Stop Making Sense is deservedly renowned as one of the all-time great concert films, a tour-de-force of expressionist visuals, boundless energy and tight-knit art rock so compelling that even The New Yorker’s famously hard-to-please film critic Pauline Kael hailed it as “close to perfection.”

Inevitably, without the surreal sight of Byrne’s boxlike suit, the Metropolis-inspired backdrop or the unorthodox manner the Heads entered the stage one-by-one, the live album that came with it loses some appeal. It also doesn’t help matters that its 18-track setlist is cut in half either. Nevertheless, the chosen nine, taken from the group’s four-night residency at Hollywood’s Pantages Theatre in December 1983, still captures the buzz and excitement.

Spanning all their first five studio efforts, plus a rare band outing for What A Day That Was from Byrne’s solo album The Catherine Wheel, it’s a fair representation of their consistently strong back catalogue. Not that you’d immediately recognise it, of course.

The typically frantic post-punk of Psycho Killer is performed by Byrne alone with nothing but an acoustic guitar and Roland TR-808 drum machine for company. And it takes until the fourth track, a storming rendition of Burning Down The House, for the entirety of the Heads’ regular live set-up to make their presence known. But Once In A Lifetime, which unlike the studio version, made the Billboard Hot 100, and Life During Wartime, famously accompanied by an aerobics workout that Jane Fonda would be proud of, may well be the superior versions.

As attested to by the likes of Lorde, The National and Paramore, all of whom contributed to the recent tribute album, it’s a record which defies logic but still makes total sense.

Little Creatures (1985)

“It’s so much fun to be able to relax and just play without feeling you have to be avant-garde all the time,” noted Weymouth to The New York Times ahead of Talking Heads’ sixth LP. Indeed, having built their reputation on subverting pop norms, Little Creatures found the group suddenly leaning into them.

Inspired by a Baltimore hippie who claimed she could levitate, party-starting opener And She Was could easily have been mistaken for The B-52’s.

Byrne even plays the crooner on the swoonsome Perfect World, albeit one still prone to the odd whoop and holler. And their only UK Top 10 hit, Road To Nowhere, remains their most concerted bid for the mainstream, throwing in Cajun accordions, military beats and a gospel choir on a self-described “joyful look at doom.”

Just as remarkably for a band never more than a chord change away from a baffling metaphor, the lyrics strayed into the relatively conventional, too. “Well, I’ve seen sex and I think it’s alright,” comes the glowing review on country number Creatures Of Love about a subject previously off-limits. It was an approach that reaped rewards: with more than two million copies sold in the US alone, Little Creatures is by far the highest-selling release in the Heads’ oeuvre. It might not be the purists’ favourite, but it proved that the band could still delight and intrigue in equal measure when they ventured outside their art school wheelhouse.

True Stories (1986)

A curious concoction, True Stories is essentially an alternative soundtrack to the same-named film in which a cowboy-hatted David Byrne roams around a fictional Texas town in a red Corvette (“like 60 minutes on acid,” he later described the kitschy musical satire). But instead of the original cast recordings, which included contributions from Swoosie Kurtz, Spalding Gray as well as a pre-Roseanne John Goodman, Talking Heads take over all duties on nine of the most straightforward tracks of their boundary-pushing career.

No doubt reflecting the movie’s setting, the group fully embrace the sounds of the Southwest, with anti-consumerist opener Love For Sale, waltz-like Dream Operator and boomer nostalgia of People Like Us (“In 1950 when I was born/ Papa couldn’t afford to buy us much”) all heavily indebted to good old-fashioned country.

Then there’s the uplifting Tex-Mex Hey Now, the conspiracy theory-peddling rhythm and blues of Puzzlin’ Evidence and, of course, Radio Head, an accordion-led party anthem which inspired the name of another revolutionary alt-rock outfit.

And while Byrne was previously disdainful of Americana, most notably on the scathing The Big Country, he’s now positively salivating over it. Sentimental closer City Of Dreams, for instance, celebrates both the history and future of his newly beloved hometown (“Underneath the concrete, the dream is still alive/ A hundred million lifetimes, a world that never dies”) with the same gusto Bruce Springsteen does over New Jersey.

Although it spawned their final US Top 40 hit, Wild Wild Life, and two MTV Video Music Award wins for its cabaret-themed promo in which Jerry Harrison lampoons Prince, Billy Idol and even The Karate Kid, True Stories appears to be the most unloved entry in the quartet’s slim but impactful discography. Like the film itself, which grossed $2.5 million at the box office, it came and went without much of a trace. Nevertheless, even when veering into the mundane, the Heads are still more inventive than most of their peers.

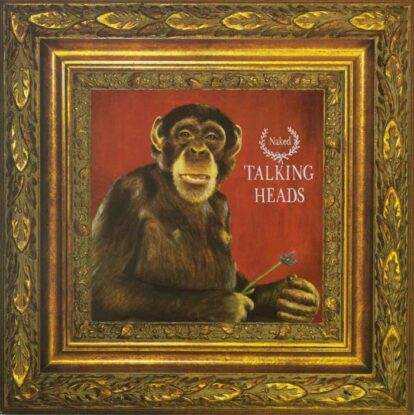

Naked (1988)

Possibly burned by the middling response to their mid-80s output and the fact that Paul Simon’s Graceland had aped their best moves, Talking Heads returned to more adventurous territory on what sadly became their studio swansong. There are still tentative concessions to the mainstream. Ruby Dear borrows the Bo Diddley beat that helped take U2’s Desire to No.1 just six months later, while the gently swaying blues of Bill could almost be mistaken for Chris Rea.

But elsewhere, Naked prides itself on out-weirding the opposition, toying with everything from carnival jazz (Mr. Jones) and freak-funk (lead single Blind) to industrial (The Facts Of Life) and soukous (Totally Nude).

Byrne said the record was “about human beings stripped of their pretensions,” no doubt explaining the chimpanzee cover art and how it was conceived via improvised gibberish.

Luckily, the latter was substituted for something more profound, with The Democratic Circus tackling the regular subject of consumerism and Mommy Daddy You And I immigration.

Meanwhile, (Nothing But) Flowers envisions a future where the environment has fought back against destructive mankind, much to Byrne’s disdain. Three years later, Talking Heads went permanently quiet.

Live At WCOZ 77 (2024)

As its name suggests, Live At WCOZ 77 borrows from the same radio session that kicked off The Name Of This Band Is Talking Heads several decades previously.

But instead of just five numbers, this Record Store Day release serves up the entire 14-track setlist from their performance at Massachusetts Northern Studio in all its glory.

That means fans get to hear three additional songs from their seminal debut, released only a couple of months earlier, including Uh-Oh, Love Comes To Town, Who Is It and The Book I Read.

What’s remarkable for a band still very much in their infancy is how tight and self-assured they sound, and how they maintain their unrivalled sense of rhythmic energy from the moment they burst out of the blocks with Love ’ Building On Fire to their closing rendition of Pulled Up.

There are also early outings for Thank You For Sending Me An Angel, The Good Thing and Take Me To The River.

And while their primitive but rousing forms highlight the magic that Brian Eno worked on their future home More Songs About Buildings And Food, they still signal how effortlessly the fledgling outfit shook off their CBGB roots, ultimately becoming one of the Big Apple’s most defining bands.

A transformative and pivotal moment in the band’s trajectory.

Visit the Talking Heads Official Store here

Subscribe to Classic Pop magazine here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.