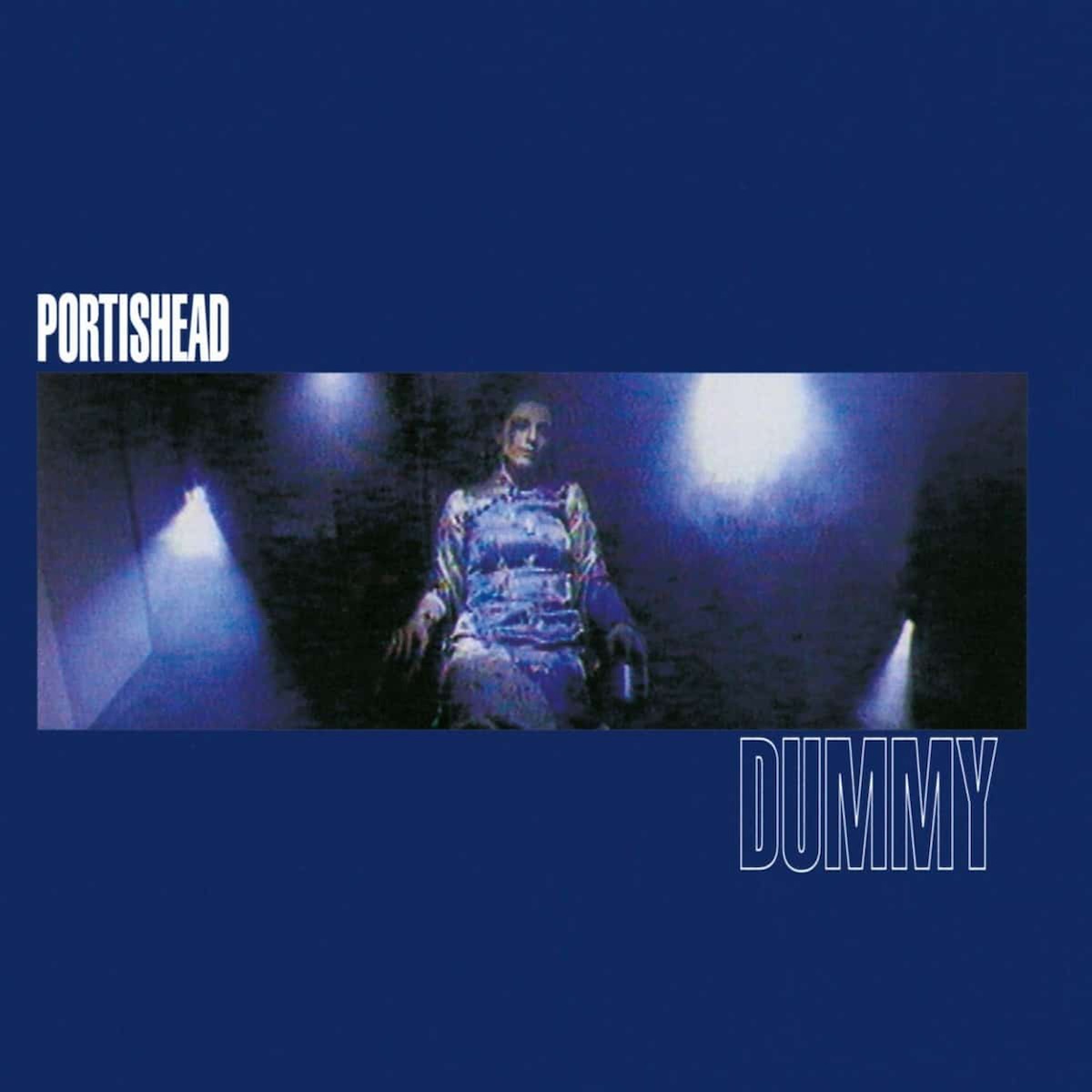

The Bristol group’s debut long-player is a sultry, smoky and fiercely original classic that blends looping beats with twangy guitars and seductive vocals

Portishead’s Dummy is a hauntingly beautiful masterpiece that continues to captivate listeners with its moody elegance and groundbreaking sound.

1994: a watershed year for British music, whatever your tastes. Blur’s Parklife, the Manics’ The Holy Bible, The Prodigy’s Music For The Jilted Generation, not to mention a cracking debut single from Supergrass and, of course, Oasis’ Definitely Maybe. But none were quite so singular; so boldly original and notably out of step as the introductory offering from Portishead. Dummy, released in August that year, was as brilliant as it was unexpected – one of the most influential British debut records of its era.

And just as Britpop was in full swing, sending acoustic guitar sales through the roof with supercharged lad-rock anthems tailored for the terraces, a sleeper-hit revolution was under way in Bristol. It began as a low rumble of bass – one you could feel rattling in your bones long before your ears could even hear it; the warm crackling and popping of vinyl static; slow, hypnotic grooves and ethereal vocals. Pitched quite deliberately at the opposite end of the spectrum, Portishead’s Dummy was everything that Definitely Maybe or Parklife wasn’t: subtle, slow-burning, elusive, delicate, haunting.

But dinner party music this ain’t. If your host should slip Dummy onto the turntable before serving up the hors d’oeuvres, it might be wise to politely make your excuses. Exquisite taste in music aside, there’s a good chance the canapés have been laced with cyanide. Far from the ‘chill out’ tag too often lazily applied to this group, ‘chilling’ would be more appropriate. Portishead’s debut is at times awkward, intense, demanding, anxious and sinister. For all its lighter moments (It Could Be Sweet), it gets pretty heavy, too (that groove in Strangers).

Musical Melting Pot

The Bristol Sound* evolved out of the city’s sound systems, melding influences from US hip-hop with a distinctly Bristolian sensibility, informed by the city’s rich (albeit troubled) multicultural heritage, and influence of dub from incoming Afro-Caribbean communities. (*Don’t call it ‘trip-hop’, unless you wish to invoke the wrath of its originators.)

The creative clash of cultures nevertheless fuelled a subversive artistic outlook that fed into the music. One such collective, The Wild Bunch, spawned scene icons Massive Attack and their occasional associate Tricky, as well as Grammy award-winning producer, Nellee Hooper, while the same scene birthed the famously elusive street artist, Banksy.

The Bristol set jettisoned the alpha male braggadocio typically associated with hip-hop, electing instead for hushed vocals, a meditative, soulful sensuality, and – a total taboo in hip-hop at the time – occasional gender-fluidity. The pace is positively sedate yet unrelenting, like a freight train gradually building momentum. Contrary to Madchester’s rave culture, that was all about coming up, Bristol soundtracked the comedown, representing the internal rather than external. “Dance music for the head rather than the feet”, to quote Massive Attack’s Daddy G in The Observer.

Sculpting New Sounds

While Portishead were not born directly out of that scene, they were close enough to absorb some of its attributes. A teenage Geoff Barrow was the assistant at Bristol’s Coach House studio, meaning he learnt his trade on Massive Attack’s seminal record, 1991’s Blue Lines, the genre’s holotype.

Mobilised by the novel techniques they deployed, Barrow picked up a thing or two from Massive Attack – specifically, an Akai sampler and an Atari computer, with which he began to sculpt new beats and sounds of his own.

These formative explorations on the borrowed gear – initially flying solo – were the genesis of what would evolve into Portishead.

On the face of it, the Portishead trio made an unlikely ensemble, each born in a different decade: Adrian Utley in the 50s, Beth Gibbons in the 60s and Geoff Barrow in the 70s. Yet each brought a distinct element that was integral to their sound.

Barrow was the group’s driving force, heavily inspired by hip-hop, fascinated by its techniques of sampling, looping and turntable scratching. Barrow’s writing and production credit (Somedays) on Neneh Cherry’s 1992 album, Homebrew provided a first professional release; his dusty, minimalistic beats are very audibly the precursor to the Portishead sound.

Retro Noir

While attending an enterprise course for the unemployed, Barrow met would-be singer, Beth Gibbons – an incredible raw talent with a voice like cut glass. In an alternative universe, Gibbons might have become the official frontwoman of Talk Talk offshoot, .O.rang (Beth appears on their 1994 debut album, Herd Of Instinct). Ultimately, the burgeoning success of Portishead took her on a different path.

Naturally shy, the young Beth is invariably seen stooping over the microphone, as a cigarette slowly burns down between her fingers. She giggles her way nervously through interviews, so unaccustomed is she to the limelight. But when she sings, she’s a force of nature. Her body becomes a portal that transports the listener back to another era, familiar but tantalisingly out of reach. Her voice does not belong in our time; perhaps a lost wartime radio transmission somehow making its way out of the ether into a crackly Tannoy speaker.

The final piece of the puzzle to slot into place, Adrian Utley was carving out a living as a jobbing musician for the likes of Jeff Beck, among others. The man with the golden guitar, Utley brought the spy film element. Utley was drawn to film composers such as John Barry, who scored much of the James Bond series, and Ennio Morricone, known for his spaghetti western soundtracks. Utley opened Barrow up to these novel sounds – a defining ingredient in Portishead’s chemistry that clearly differentiates them from their comrades in Massive Attack. Cue oodles of sweeping strings, jazzy interludes and twangy tremolo guitars, invoking a distinct retro noir sensibility.

Dust & Distortion

Dummy achieves perfection through imperfection. Atmosphere and ambience remain at the forefront throughout; the space between the notes carrying a weightiness of its own.

The trio went to extreme lengths to create those timeless smoky sounds. One such technique was bouncing down to cassette; or transmitting Beth’s vocals to tape via a radio signal; or playing through a broken amplifier – each time, taking a clean signal and pushing it through a degenerative format to create loss and distortion. In other.

This approach even extended to sampling themselves: recording original drum grooves to vinyl, which could then be manipulated. Utley brought in fellow jazz session player, Clive Deamer – quite possibly the only drummer to have been thrown out of a band (Hawkwind, no less) for being “too professional”. Deamer would play the beat, as requested, which they’d cut to a master disc, before scuffing it up and wearing it out (until it resembled a bargain bin record picked up at a car boot sale), resampling, and then chopping it up to their satisfaction.

Great sampling is a genuinely overlooked artform – not just the technical prowess, but the curatorial aspect of selecting the right choices and incorporating them into one’s own sound in a way that adds something new. Utley’s classic record collection evidently influenced a few key samples on Dummy. While Sour Times and Glory Box clearly owe their essence to the source material, Portishead’s own innovation takes them somewhere excitingly new.

Elsewhere, the samples are deployed in a way that skews them entirely from recognition into something wholly original and otherworldly – the prime example being the line from 50s crooner Johnnie Ray’s I’ll Never Fall In Love Again, gloriously subverted on Biscuit to resemble some abstract signal phoned in from outer space.

Out On Their Own

The word that continually crops up when describing Portishead is ‘uncompromising’. As a unit, they are anti-popstars in every sense, known for being elusive and finding success on their own terms, and avoiding the usual commercial promotional activities. They are very much a studio outfit by nature. Nevertheless, 1998’s Live In Roseland NYC, recorded in support of their second, self-titled LP, is an absolute masterclass. Featuring a full live band and orchestra, it’s a phenomenal document for a collective who, by their own admission, once said they didn’t enjoy playing live. It’s also testament to their development from a sample-based origin to an organic instrumental group.

Released in a year of epic albums, Dummy nonetheless won the Mercury Prize, beating stellar debuts from Britpop boomers Oasis, Supergrass and Elastica, as well as fellow Bristol alumni, Tricky.

Peaking at No.2 on UK Albums Chart, Dummy was eventually crowned as record of the year by both Melody Maker and The Wire and has since become a fixture on ‘best of’ lists. Indeed, what’s amazing about Dummy is how it transcends genre. Whatever tribe you belong to, something resonates within.

Widespread Influence

Portishead’s legacy is most clearly measured, not in their own near perfect but limited output, but rather the huge amount of copycat material that followed. You hear Dummy’s influence rubbing off on a multitude of artists who found commercial success in Portishead’s wake: Groove Armada, Morcheeba, Goldfrapp, Air, Cinematic Orchestra, Zero 7. While not without merit, many of them sanded off the rough edges that gave Portishead their character. More recently, Lana Del Rey and Billie Eilish have taken cues from their retro-inspired streetwise melancholia. Beth Gibbons’ voice is much imitated, but never surpassed.

Their sound (if not their style) has clear echoes in Danger Mouse’s Noughties production work, notably on Beck’s 2008 album Modern Guilt, which features sparse arrangements of reverb-laden plucked guitars over crunchy beats, characterised by the same analogue warmth and vintage sound.

Portishead’s aesthetic became so recognisable, ubiquitous and emulated, that they consciously scrapped it entirely, wiping the slate clean for the long-gestated Third album. If not for Beth’s voice, you’d never consider it to be the same band – which, presumably, is precisely what they wanted. Gibbons recently received another Mercury nod for her 2024 solo LP, Lives Outgrown (Time’s album of 2024) – an earthier, folky delight in the vein of Siouxsie. Nothing like Portishead, but equally spellbinding. You have to admire their steadfast refusal to tread the same old ground. But for this writer, Dummy remains their ultimate calling card, yet to be surpassed.

The Tracks

Mysterons

Woozy broken chords ring out over turntable scratching, before a snappy, trippy beat falls in on a tautly wound snare, accompanied by a spooky theremin. Gibbons’ timeless voice enters the fray, lifting the track from a breakbeat instrumental into something boldly original. As far as introductions go it’s pretty compelling; the consummate soundtrack to a lost silver screen classic: film noir meets B-movie sci-fi.

The title, of course, references the puppet-based sci-fi show from the makers of Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet And The Mysterons. Various interpretations of the latter have been put forward, such as it being a commentary on the Cold War and/or the psychological tactics deployed by terrorists. Despite the extraterrestrial sci-fi theme, could Portishead’s reference be a foreboding comment on looking not outwards, but inwards, at our own dark human nature? Or maybe the title just sounded great.

Sour Times

One of Portishead’s defining tracks and a masterclass in understated cool, Sour Times is built around the opening bars of Danube Incident from the original Mission Impossible series, recasting it as a sultry ballad. It boasts one of Portishead’s trademark descending plucked basslines, twangy, high tremolo guitars, plus the rattling and chiming cimbalom. Gibbons coos gently: “Nobody loves me, it’s true/ Not like you do”, over a shuffling beat. Upon initial UK release, the single stalled at No.57, later reaching No.13 on re-release following the success of Glory Box. A smoky and timeless classic.

Strangers

A Weather Report sample collapses into a gnarly, repetitive and dubby groove, akin to Massive Attack. That’s before a slinky guitar part and hints of mangled trumpet transport us to the jazz café. The abrasive low-end pulse is wonderfully hypnotic, punky and dissonant, like an air raid siren, with Beth’s voice cutting like glass over the top.

A hugely original highlight of the record, that truly comes alive at their gigs. Indeed, even more satisfying than the song itself is checking out reaction videos of the Roseland NYC performance from uninitiated listeners – watching their minds get blown (in a good way) through a combination of sheer joy and total confusion is truly heartwarming.

It Could Be Sweet

The first track that Gibbons and Barrow ever worked on together, before Utley joined them. Apparently, Beth already had an idea in progress, which Geoff then re-translated into his formative Portishead sound. He utilises a drum machine to create a proto trap groove – a simple backbeat at a chilled-out tempo, juxtaposed with fluttering syncopated fills.

As a first ‘testing the water’ collab, it’s an impressive statement of intent, though the intensity they would go on to achieve has not yet fully developed. It’s notably one of the more upbeat and uplifting tracks on the album; breezy and carefree, without the foreboding sense of dread and anxiety that hangs over much of the record. Though it is comparatively lightweight in tone, that’s no bad thing to counterbalance the shade elsewhere.

Wandering Star

Instantly more foreboding than the previous track, Wandering Star is built upon a slow pulsing emission like a broken heart monitor, that incorporates a manipulated sample, against a slow baggy beat. There’s more funky turntablism from Barrow and down-tuned guitar licks from Utley. Without Beth’s voice, it could pass for an instrumental from Californian rap collective, Jurassic 5’s debut.

Throughout the LP, Gibbons’ lyrics are often abstract and ambiguous – yet, even when you’re not entirely clear of the meaning, they invoke various emotions, ranging from isolation and loneliness to yearning and seduction. Sample lyrics in this case: “The masks that the monsters wear to feed upon their prey” and “the blackness of darkness forever”. The sinister monotony of the groove and vocal contrasts with the uplifting guitar and turntable embellishments.

It’s A Fire

Opening like Massive Attack’s Unfinished Sympathy with majestic sweeping strings, it then takes a different direction with Beth’s vocal over organ chords, easily passing for an offcut from Air’s Moon Safari. Missing from the tracklisting of some original releases of the album, it’s fine and a serviceable chill-out track but feels a little like they’re coasting, lacking the same intensity felt across Dummy. It’s direct, clear and upfront (no bad thing in itself), but not cloaked in that cloying atmosphere that gives the rest of the record its visceral edge.

Numb

This is much better, a skulking groove with a real dub reggae feel akin to Massive Attack’s Karmacoma. With lots of space, tape echo, wonderful organ stabs and a minimalistic, spooky, isolated feel, Numb is essentially The Specials’ Ghost Town for the trip-hop generation. The track features some fine scratching from Barrow, chopping in masterfully obscured snippets of Ray Charles’ I’ve Got A Woman, and a close, haunting vocal from Gibbons. Issued as the record’s first single, it criminally failed to chart.

Roads

This era-defining classic demands to be savoured in decent headphones, cranked up, with eyes closed. Apparently, it was named after the Fender Rhodes that the signature progression was performed on (as played by Neil Solman).

Those beautifully woozy keys pulse and tremble, shivering up your spine, later joined by silky strings and Utley’s jazzy guitar with more wah wah-laden tremolo. Beth’s falsetto is so clear and pure, it rings like a bell. Roads features prominently in the post-apocalyptic film Tank Girl (from Gorillaz artist, Jamie Hewlett), but why on earth wasn’t it a single? Portishead at their very, very best: this is gorgeous, beautifully restrained and understated. Absolute perfection.

Pedestal

A grungy trippy beat, loaded with swagger, with a particularly jazzy vocal from Gibbons, and a muted trumpet solo that imbue a real lounge feel. Pedestal is notably sparse, moody and subdued. Some cool funky instrumental breaks and nifty scratching from Geoff Barrow lift it from feeling too downbeat. A fine album track, but they can’t all be dizzy peaks.

Biscuit

Another breakbeat jam, with more funky turntablism and the inspired Johnnie Ray sample that’s distorted, mangled and manipulated beyond recognition to create an eerily down-pitched, stretched out vocal refrain. Biscuit features another characteristic descending bassline, with lots more Fender Rhodes piano giving a lounge vibe, over a stop-start beat. Its space age jazz feels a lot like The Cinematic Orchestra, who would follow in their wake. A cool downbeat stoner vibe.

Glory Box

Whether or not Portishead are on your radar, Glory Box is the song that everyone has heard somewhere. An instant stone-cold classic and the most catchy and accessible track on the record, it lands immediately, with its simple descending bassline, lush strings refrain and screaming guitar solo.

It’s built around a sample from Ike’s Rap II by Isaac Hayes, also cheekily sampled on Tricky’s Hell Is Round The Corner off Maxinquaye. (Though note that Ike’s Rap is in itself a loose interpolation of another heavily sampled earworm, Wallace Collection’s Daydream.)

Its prettiness is subverted in the final bars, with a briefly chaotic dissonance like A Day In The Life, before resolving itself with calm. The band didn’t want to release it on the grounds of it being “too commercial”, but it made UK No.13, and its popularity gave them a solid platform on which to build.

For more on Portishead click here

If you liked this check out Focus On Bristol

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.