An exciting synth-pop debut that held such promise for the duo, yet remained enigmatic. Behind the obvious influences is a record that shimmers with greatness.

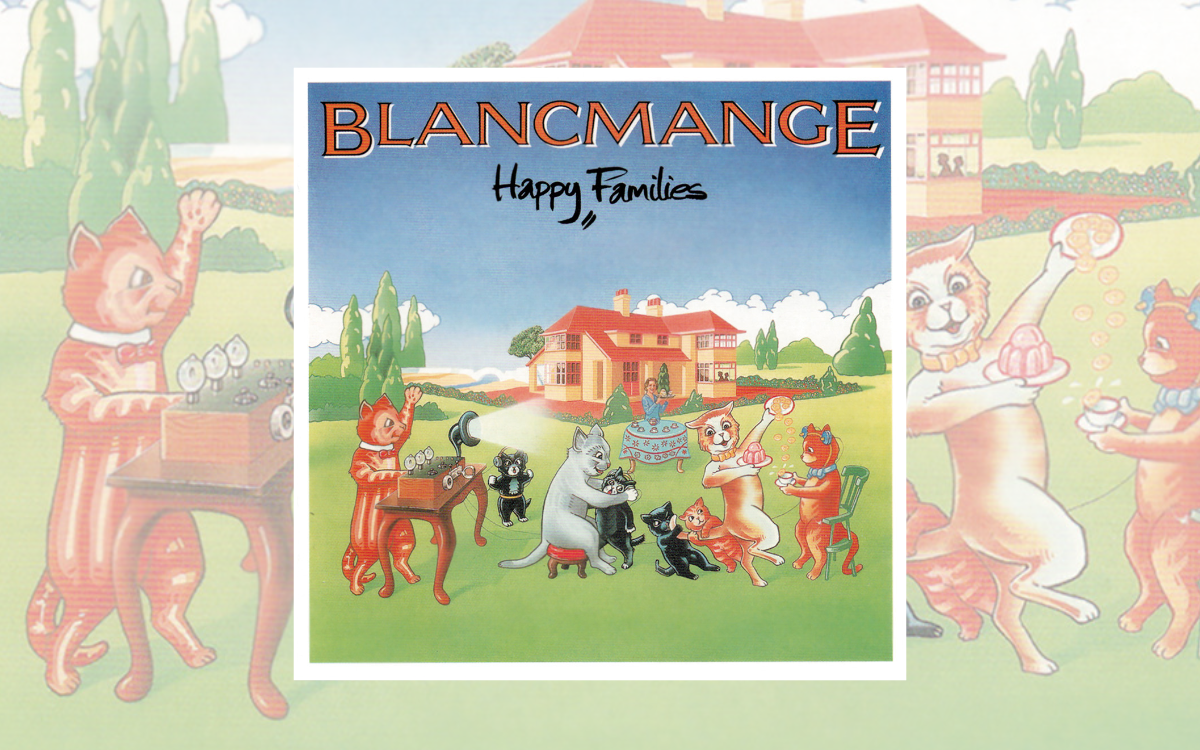

When reeling off the titans of early synth-pop, there is one particular gem that invariably gets overlooked – Happy Families by Blancmange.

Brimming with energy and hooks, it is a fine record featuring razor-sharp production, whose impressiveness only improves with age. Yet, for some reason, it’s rarely spoken of in such vaunted tones as its contemporaries. It’s time to put that right, and on this subject, we’ve got history. After all, Blancmange were Classic Pop’s inaugural ‘Godfathers of Pop’ in our very first issue, way back in October 2012.

Like so many of Britain’s national treasures, from Roxy Music to Pulp, the project grew out of art school extra-curricular activities. Neil Arthur left his native Lancashire to enrol at Harrow School of Art, where he met Stephen Luscombe, at an exciting tipping point for music in the late 70s. The duo’s experiments were not so much a career choice, as an outlet to explore their burgeoning artistic whims. Arthur, speaking to Classic Pop in 2017, said: “The music was just another means of expression. Not for one minute did we think we’d get an opportunity to take it beyond that.”

Arthur has professed their lack of musical training to be a source of pride; a continuation of the DIY punk ethos that blasted the doors open for anyone to pick up an instrument and give it a go. As far as they were concerned, the lack of schooling was an advantage. Free from the restrictions of convention, they could push boundaries and see where that took them. Formative projects included making industrial noises with household appliances – essentially, whatever they could get their hands on. “We were stupid arseholes basically, just having a laugh,” explained Luscombe in the same CP interview.

Experimental Noise

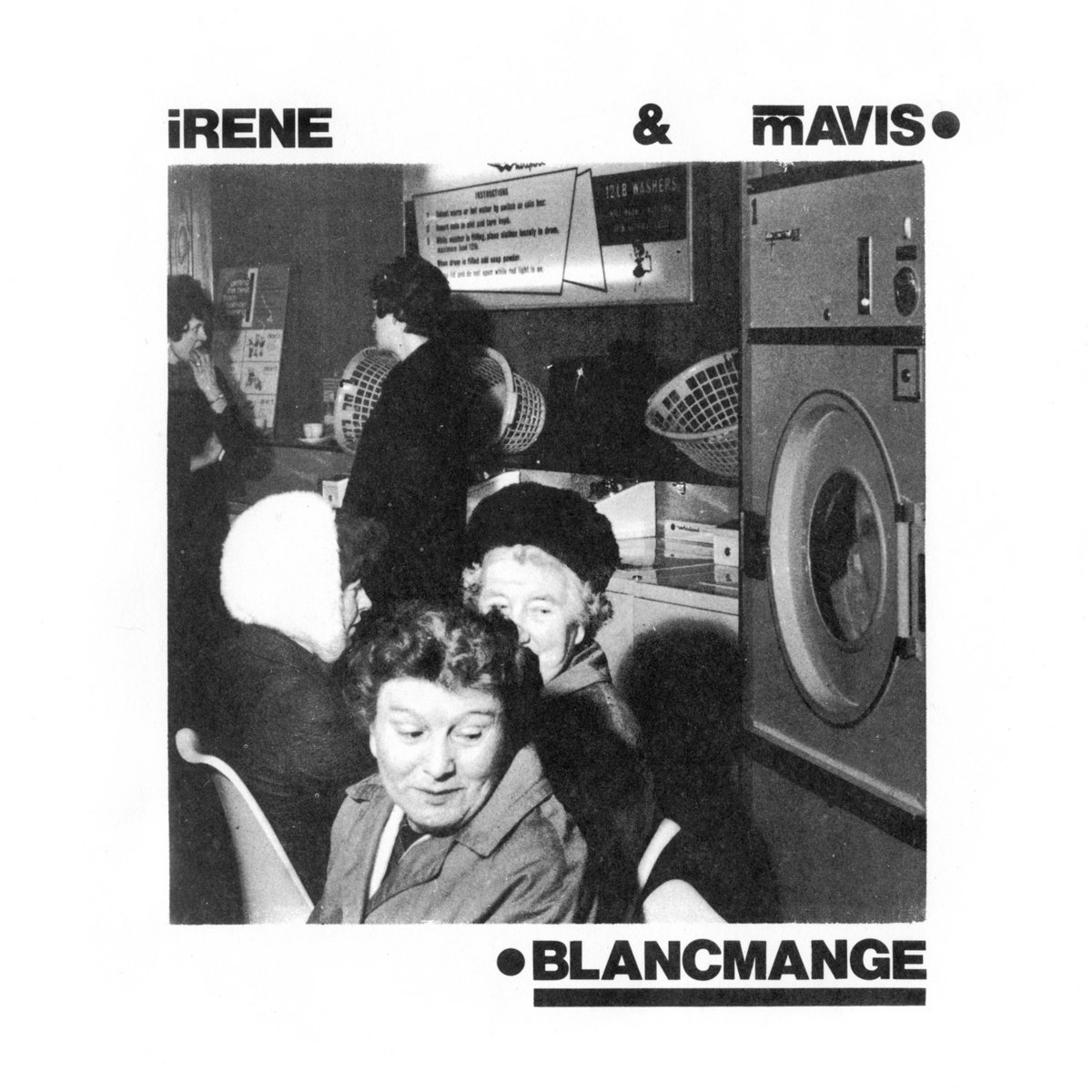

Their first EP, Irene & Mavis, recorded in 1979 and released in 1980, is a fascinating curio of the era, featuring six tracks of challenging, experimental noise.

Abstract and artily pretentious by design, on first listen, it shows little sign of the slick synth-pop band they would shortly become. But tune in closer, there’s a faintly discernible trace of the magic soon to be conjured on their full-length debut.

The band’s name itself is testament to the lack of a long-term plan or, seemingly, desire to be taken seriously. While other French-derived names selected by their contemporaries – Depeche Mode and Cabaret Voltaire, for example – are edgy and evocative of otherworldly imagery, Blancmange stubbornly does the opposite, conjuring up notions of a bland wobbly pudding. “We shot ourselves in the foot,” conceded Arthur to Classic Pop. But it could have been worse. Other contenders included ‘A Pint of Curry’ and ‘The Bleak Industrial Cooling Towers’. The latter, at least, has a certain austere gravitas to it.

Still, Blancmange gained enough momentum for a demo to be produced by synth-pop pioneer Martyn Ware, who had recently left The Human League to set up Heaven 17. What’s more, their instrumental, Sad Day, got picked up for the now-legendary Some Bizzare Album compilation in 1981, which featured a who’s who of tomorrow’s movers and shakers: Depeche Mode, Soft Cell and The The. With their star on the rise, a deal was inked with London Records and they got to work on the debut album.

Battery Powered

The album was recorded at London’s CBS and Battery Studios, with producer Mike Howlett, a man on top form at that point in the early 80s and enjoying a phenomenal run of hits. The result is a lean, sharply-focussed and self-assured set of 10 tracks.

Talking in a 2014 MusicTech interview, Arthur explained that the instrumental mainstays were the Roland TR-808 drum machine, the Roland Super Jupiter synthesizer and the LinnDrum. The classic workhorses of synth-pop, and a ubiquitous presence throughout the 80s charts.

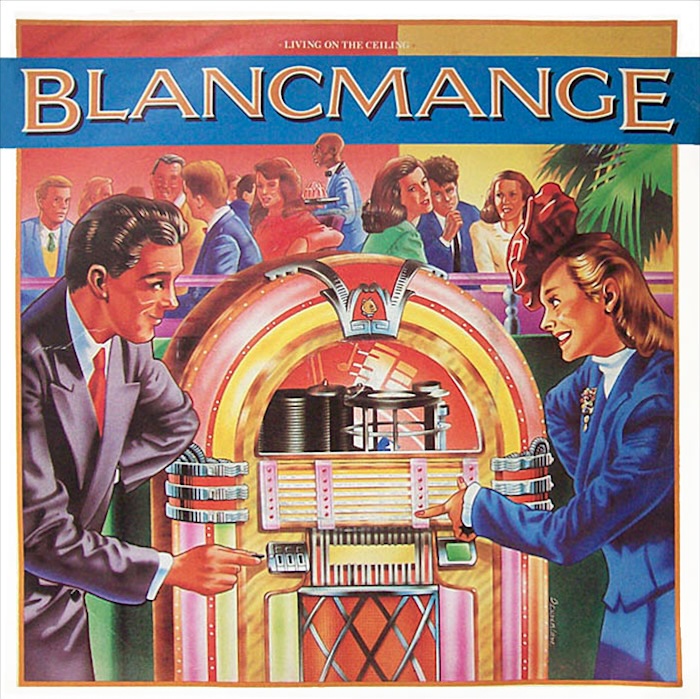

However, it was the inspired addition of Pandit Dinesh on tablas and Deepak Khazanchi’s sitar, that elevated their breakout hit, Living On The Ceiling well above the average fare. It showcases the pair at their most innovative, and its potency continues to resonate today. Arthur has compared the main riff’s melody as akin to a football chant at live shows.

Charismatic Vocals

Another defining feature across their output is Arthur’s charismatic vocals. In their earliest incarnation, it was sideman Luscombe who assumed the role of singer. But Arthur’s casually impressive Elvis and Johnny Cash impressions, while fooling about, ultimately pushed him centre stage. Clearly, he has a natural knack for aping other’s vocal styles, though his detractors would suggest this has been achieved at the expense of developing his own.

Arthur hops between characters, often affecting a different voice to fit the mood, his natural baritone providing the foundation for uncanny soundalikes of David Byrne, Dave Gahan and Ian Curtis. On the big hitters – like Living On The Ceiling, Feel Me and God’s Kitchen – there’s no denying he’s indebted to Talking Heads, albeit set to a more electronic backdrop.

Nevertheless, the similarity occasionally borders on parody, even when the results are thrilling. It’s the paradox at the heart of Blancmange, and a recurring bugbear of critics centred on authenticity. As several contemporary reviews, from Melody Maker to Smash Hits, contended, there’s a recurring feeling of playing dress-up; of not really believing what they’re doing – a point reinforced in their own frank admissions of amazement for getting as far as they did.

You Raise Me…

Performing on The Tube in December 1982, Arthur’s inter-song banter extends to a call out to his mum to put a pie in the oven, as he’ll be back home soon. He’d never embrace the rock god persona of, say, Dave Gahan, but it’s that flippant cheekiness that’s key to his charm. Still, at times, the sense that it’s all tongue-in-cheek slightly undermines the impact of the delivery, particularly when they play it straight on a subtle heart-wrencher like Waves.

The album reached No.30 in the UK and Blancmange briefly enjoyed a taste of the top tier with several Top 20 hits. Their later cover of ABBA’s The Day Before You Came, even outperformed the original.

But ultimately, they remained underdogs and never quite made that final step to become arena fillers, despite having the songs to back it up. By album three, they had ultimately tired of the industry machine… and each other, deciding to quit.

…And Then You Let Me Fall

Today, Living On The Ceiling remains a classic floorfiller, and Happy Families is the group’s calling card. So much so, that, when invited to tour the record in 2013, Arthur decided to go one better and recreate the entire LP as Happy Families Too…

There’s a current phase for re-recording classic albums, for purely fiscal reasons, to take back control of the master tapes. However, Arthur’s decision came from a love of the craft and a desire to present a gift to the fans, offering a fresh take with the latest tools available. Evidently, he desired to go back and ‘fix’ issues and bring the sound up-to-date. But, really, there was nothing in the recordings that needed a modern refresh. Certainly, it’s much cleaner sounding, with some nice flourishes. But everything is a product of its time and, as customary with remakes – however faithful, it makes you pine for the original.

Luscombe had to step back from the ongoing revival for health reasons, but Arthur is still touring and recording today under the Blancmange banner, working at a prolific rate. In fact, he’s released about five times as many Blancmange records in the last 10 years than the pair did in their 80s run.

Arthur comes across as someone who can’t quite believe his luck at the situation he’s found himself in. This comes to the fore in the promo videos, where he’s practically laughing while lip-syncing, dropping the façade to marvel at the absurdity of it all.

If The Hat Fits

While Blancmange has evolved naturally, Happy Families documents an act trying on various hats and still finding their own sound. It’s an enigma: a record positively stuffed with creativity and ideas, yet also clearly indebted to their contemporaries. But aping heroes and latching onto the current trends is pretty standard stuff for any fledgling act on their debut album. Just listen to Simple Minds’ first record – they just stuck it out long enough to forge a unique sound.

No-one who has seen Blancmange perform could honestly deny their obvious passion for what they were doing, nor the sheer talent clearly on display.

Today, Arthur continues to resonate a love for the craft and his audience. Perhaps, in their youth, their Achilles heel was not realising quite how good they really were. When they did let that mask slip, Happy Families and ensuing records revealed signs of greatness.

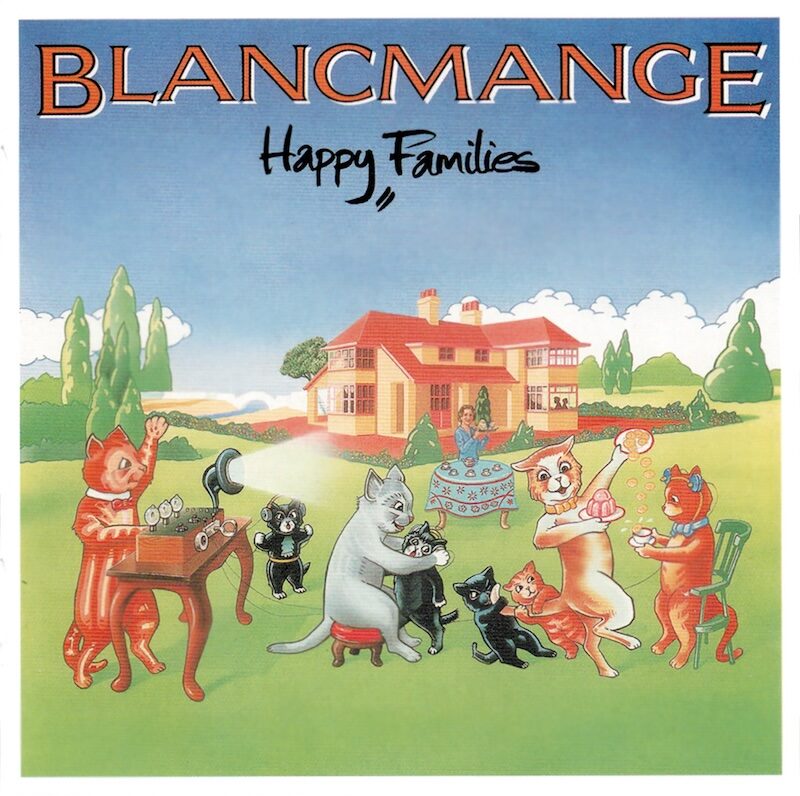

Indeed, there’s another way to view Blancmange – an underacknowledged act that sits within that long, healthy lineage of English surrealist eccentrics, from Syd Barrett to The Mighty Boosh. The idiosyncrasy is echoed in the cover art, featuring a painting an anthropomorphic cats’ tea party, heavily inspired by English eccentric, Lois Wain – another underdog hero, whose colourful illustrations pre-empted psychedelia in the early 20th century.

Happy Families is best enjoyed for what it is – a collection of irresistible songs that engage the head and the feet.

The Tracks

I Can’t Explain

As the needle drops, it’s straight to action with a sprightly, jittery electro beat with synthesized handclaps, a rhythmic synth bassline, and guitar stabs used sparingly – not playing melodic lines, but designed to create percussive pulses. Instrumentalist Stephen Luscombe makes his presence felt with an industrial, sinister vibe, as saw-wave synths bleep in like sirens signalling the apocalypse. The result is something inherently ominous and unnerving. A promising start, Neil Arthur then arrives with angular vocals reminiscent of David Byrne’s manic preacher, delivering the sermon, with gospel-like female backing vocals offering a rousing counterpoint. Meanwhile, the guitars increase in intensity. At the halfway point of the track, the mood takes a sudden downturn, becoming increasingly unnerving in a melodic section; descending chord transitions carry a sense of foreboding dread. To cap it off,a manic Arthur shouts, “I can’t explain, no, I don’t know how I feel!” An unsettling and charismatic opening, and there’s something of The Cure’s claustrophobic intensity.

Feel Me

A true masterclass in production, Feel Me opens with a slightly slower, menacing, skulking groove courtesy of Luscombe, that nonetheless skips along with steady intent. This time, Arthur opens more like Depeche Mode’s Dave Gahan in the vocals, showcasing a rich and mesmerising baritone. But then in the second verse, he’s back to David Byrne with the unhinged, screaming vocal tics, and more surrealist lyrics about “a banister flying through a plate-glass window”. It bubbles over with a nervous, twitchy energy throughout, that’s irresistible. Despite wearing its influences flagrantly, it’s undoubtedly one of the finest cuts on the record. Released as a single in July 1982, preceding the album, it just missed the UK Top 40, reaching No.46.

I’ve Seen The Word

After the initial one-two punch of I Can’t Explain and Feel Me, the duo pull things back a little on I’ve Seen The Word, which offers a more subdued sound. It is equally intense, though occupying a different headspace. This time, the vocal muse appears to be Joy Division, as Arthur channels Ian Curtis’ deep timbre and elongated melodic phrasing. “I’ve seen people laughing in churchyards,” he croons mournfully, over a skittish LinnDrum rhythm, as plaintive chiming synth melody lines rise up to the heavens.

Wasted

Wasted opens with atmospheric ambience and mysterious snatched samples of speech, invoking a newsreader or political commentator, including the protestation that the subject in question “should have the right to determine their own future”. Despite the weighty scene-setting, it’s instrumentally one of the more lightweight songs once the main track gets going, with bouncy synth sounds playing a standard pop chord progression, almost doo-wop-like. It’s like very early Vince Clarke-era Depeche Mode, before the band went dark. Again, the deep baritone vocals sit somewhere between Curtis and Gahan, though lyrically its simple rhyming scheme feels a little naïve and underdeveloped, “Who’s to blame? We’re all the same.” A whistled melody in the fade-out adds a feeling of whimsy.

Living On The Ceiling

From the instantly accessible opening bars, it’s insanely infectious, with an idiosyncratic beat. Arthur has noted how the off-kilter hi-hat groove was achieved by accident of their drum-machine programming naivety, yet that it brought a distinct character they couldn’t have achieved from a natural human player. The rhythm and vocal stylings, are reminiscent of those on Talking Heads’ Speaking In Tongues released the following year. While the Byrne inspiration is obvious, Arthur’s native Lancashire accent comes out in his comedically egged-up enunciation (“I’m up the bluddy tree!”). The secret weapon is the killer main hook played on the sitar, infusing an inspired Eastern influence. Their biggest hit, the single sold over a quarter of a million units in the UK, made No.7 in the charts, and also resonated overseas, going Top 5 in Australia and South Africa.

Waves

Smash Hits may have derided it as “rotten”, but, clearly, they missed the point. While obviously more subtle than the preceding single (Living On The Ceiling), that is its strength. Waves is beautifully understated; a refreshing example of Blancmange’s brilliance when simply playing it straight – a hint of what they could have explored further. “I wrote the idea in an old caravan on a council road repair depot at Rayners Lance,” Arthur told The Strange Brew in 2020. “The Young Marble Giants and Scott Walker were my inspiration.” On the original pressing of the record, Waves came without strings attached. But by the time of the single release, it featured fluttering, shimmering orchestration, which adds a smothering of organic warmth over the cold, steely synths deployed elsewhere.

Kind

A change of pace, Kind opens sounding like something straight off the Top Gun soundtrack with crashing synth tom-toms, a drivetime rhythm and clanging, chorus-laden guitar chords (which have now dated its sound). It then morphs into something a little closer to OMD. There’s a ‘soul train’ feel, chugging along with some powerhouse “save me!” diva backing vocals and the walking bassline. Kind is something of an outlier on the record, not immediately sitting comfortably next to other songs stylistically. Not a bad album track by any means, but nor is it the one most fans will be calling out for at the encore.

Sad Day

The track that really started it all, when it appeared (in an earlier form) on the Some Bizzare Album in 1981. Sad Day, as its title suggests, presents a more reflective tone and relatively sedate pace, a much sparser arrangement than the preceding track. An instrumental, building around a revolving guitar line, that’s enhanced as the beat kicks in. It feels like an intermission of sorts – either mid-album filler, or a much-needed refresher, depending on one’s tastes. Arthur’s voice is so intense elsewhere, a brief instrumental reprieve isn’t such a bad thing.

Cruel

A slowburner with a minimalist backing track and sweeping synth flourishes for added drama. Vocally, it’s another DM-style ballad, with Arthur once again sounding a lot like Dave Gahan, but with a hint of Martin Fry’s ABC glamour and a touch of Philip Oakey – particularly in the lyrics, which deal with relationships more directly than some of the abstract songs.

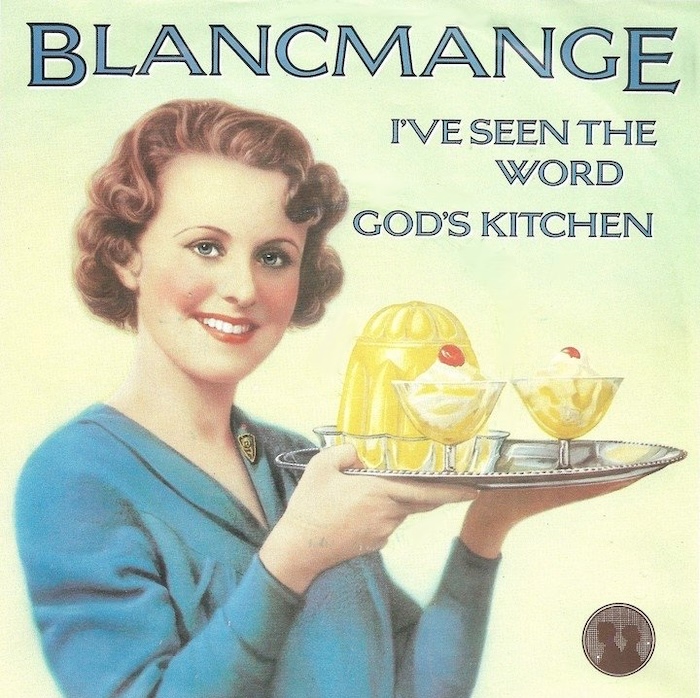

God’s Kitchen

Opening with a fantastic synth riff that smacks the listener in the face followed by the quick slaps of the handclap. Arthur is back to sounding like David Byrne again, with the uncaged, stream-of-consciousness delivery. These contrast with the slightly creepy spoken-word sections, like Barry White on a bad day. Luscombe offers more minimalist production, featuring a skeletal guitar part from Arthur caked in chorus, reminiscent of The Cure’s sound, circa A Forest. It ends, somewhat abruptly and enigmatically, with the exclamation: “I think we’re safe.” Released as a first single before the record came out, as a double A-side with I’ve Seen The Word, in March 1982, it missed the UK Top 40, reaching No.65.

For more on Blancmange click here

Subscribe to Classic Pop magazine here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.