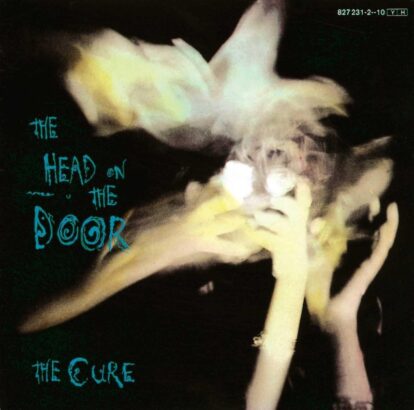

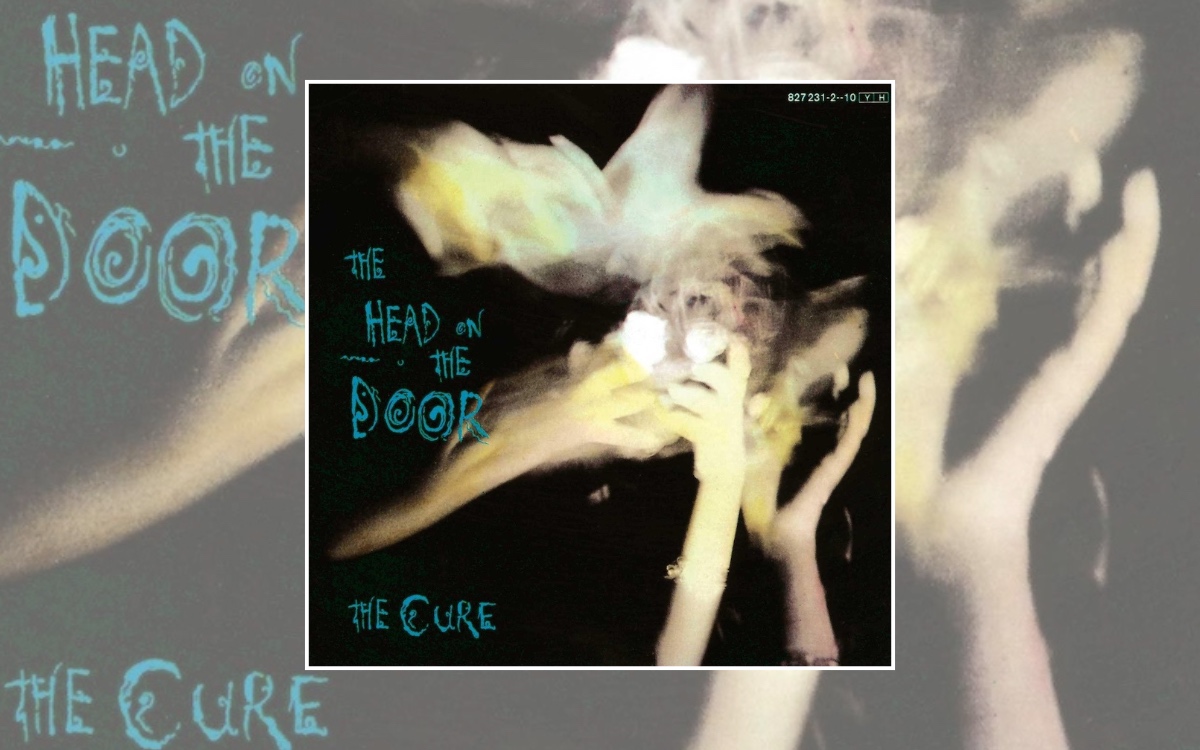

The Cure’s sixth LP is a kaleidoscope of emotion and sound which proved to be one of the band’s most captivating and accessible works

The consummate Cure album – The Head On The Door – is an eclectic brew that secured their transition from post-punk doom-mongers to bona fide pop stars and stadium fillers.

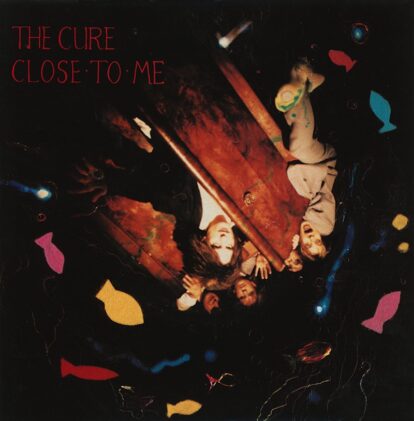

This writer will never forget his treasured copy of Now That’s What I Call Music! 18 on double tape cassette, proudly attained on his sixth birthday. That small plastic case contained an embarrassment of riches that, looking back now, would underpin a lifelong obsession with hunting down the perfect pop song: There She Goes, It’s My Life, Suicide Blonde… But the ultimate earworm that always set the bulky Walkman rattling to life was a track titled Close To Me. Nestled in between Sting and Neneh Cherry, it was a sonic bolt from the blue: a ridiculously infectious ditty, stuffed with hooks, instantly accessible, yet notably kooky and hard to place: the naïve, throwaway nursery rhyme-like hook contrasting sharply with the eerie, strained vocals, panted in hushed whispers. It was wholly original: cute yet creepy.

Curiosity piqued, a fumble through the inner sleeve revealed its makers, accompanied by a thumbnail photo of a weird looking man with big hair and smudged lipstick.

It was only many years later that its true significance became apparent. Far from the delicious novelty it first appeared, it was a calling card of one of the most influential bands in the history of popular music. As it happened, the parent album to which it originally belonged, 1985’s The Head On The Door, offered up even more gems. Any album that opens with the sublime In Between Days is off to a better start than most. While that’s a tough act to follow, the quality is maintained throughout its 10 concise tracks, each as instant and strangely alluring as the last, showcasing the many faces of The Cure.

Perfect Entry Point

The Head On The Door is the perfect entry point into the Cure canon, containing a little bit of all their signature moves in an easily accessible format: jangly pop (In Between Days and Push), exoticism (Kyoto Song and The Blood), post-punk electro (Screw), straight-up pop (Close To Me), and, of course, unbridled doom (Sinking). Whatever your favourite flavour, you’ll find it on The Head On The Door.

For their sixth studio album in six years, such a dive headfirst into the mainstream would have surprised many, given the trajectory The Cure had been on just a few years prior. Following their sprightly 1979 debut, they had carved out a defiant sound, bringing fringe cult status with their doom trilogy: Seventeen Seconds (1980), Faith (1981) and Pornography (1982) – each new release more uncompromising, bleak and dirge-like than the last.

Meanwhile, inter-band relations grew as fractious as the music, culminating in near implosion. In the ensuring fall out, Smith busied himself as the Banshees’ new guitarist, no doubt enjoying the relative anonymity of sideman. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a reshuffled Cure served up something that had been notably absent in their previous output: whimsy. 1983 standalone single The Love Cats saw them vamp it up with a camp, kitsch, Disney-inspired jazz pastiche. Although Smith would soon dismiss it as “a joke”, it provided the light relief desperately needed at that point; and it sold. 1984 single The Caterpillar followed suit.

The Head On The Door continued the trend wholesale across the entirety of an album. Smith later described this sudden switch to a poppier sound as liberating; a form of catharsis to counter the heaviness hanging over earlier records. Of course, Smith’s version of pop is still wonderfully weird, idiosyncratic and unnerving.

Wonderfully Weird

Elements that one might dismiss as throwaway are the snags that ensnare the listener, before bludgeoning them with the lyrical assault. Smith’s lyrics are still routinely oblique, like strange, visceral snapshots of dreams or nightmares. Having taken their old sound as far as it could go (for now at least), his willingness to take fresh risks demonstrates an increasing confidence as a songwriter.

The band has always been a revolving door of familiar faces, centred on the one fixed point of Robert Smith. Still, it’s not coincidental that the largely stabilised line-up he established with The Head On The Door led to their most consistently successful run. Where previous album, 1984’s The Top had been practically a solo effort, with Smith tracking most of the instruments himself, he had now found a band able to carry his widening vision forward into a new era.

The classic imperial phase line-up was secured with returning cohorts, bass player Simon Gallup and guitarist Porl Thompson. Porl was also key to the visual aesthetic, designing many of the sleeves and swirly script, including the surreal distorted photo of his future wife (and Robert’s younger sister), Janet, on this album.

Crucially, it was the first studio outing for new drummer Boris Williams, who had joined on the previous tour, having recently worked with the Thompson Twins. He beefed up their sound considerably with the pounding rhythms present on all their big hits throughout the late 80s and early 90s. Williams has the honour of introducing the album with that thunderous drum fill that opens out into In Between Days. Throughout, he produces subtle shifts and flourishes that add colour to the beat, always propelling it forwards. If Smith was the creative visionary of the songs, Williams was the driving force of the records.

Taught & Crisp

While it’s the first time Robert Smith is credited as the sole composer, it’s very much a collective effort, with each of the members adding tangible character to the arrangements. He’s since acknowledged the significance of this band’s chops, and clearly the injection of oomph spurred him to up his own game.

The other consistent figure in The Cure’s commercial transition was producer David M. Allen. A protégé of Martin Rushent, they had worked together on The Human League’s Dare – a precision-tooled production triumph that fascinated Smith. While the band had long invested in building atmosphere and intensity on record, Allen provided the means to craft more sophisticated and razor-sharp arrangements, often with a distinct electro twist. On this record more so than any other, Smith mastered the art of using the studio as an instrument, with dazzling results.

Great lengths have gone into sculpting the individual elements, so that every sound uttered on that record is deliberate though delivered with a lightness of touch. Much of The Cure’s catalogue is characterised by ambient, washy, reverb-laden doomscapes. But, by and large, the production on The Head On The Door is taut and crisp, giving a sense of closeness.

In stark contrast to those lengthier records, in which one track blends into the next in one long continuum, each song is imbued with its own signature sound. Much like The Creatures’ 1983 record Feast, the album takes cues from world music, flirting with exotic sounds from Japan to flamenco. While other attempts at such eclecticism in their career (The Top and Wild Mood Swings) ended up sounding somewhat unfocused, The Head On The Door maintains a strong sense of cohesion. It all meshes together as a body of work, albeit more akin to a singles collection.

Unmistakably The Cure

Despite spawning two of the band’s biggest hits, The Head On The Door is often overlooked in The Cure’s canon, pushed aside for those big, weighty artistic statements like Disintegration, wholly worthy of the adulation heaped upon them.While hardly a ‘lost’ record, The Head On The Door is seldom afforded the same degree of reverence. It’s neither epic nor singular.

But The Head On The Door is not bogged down by such qualms. It’s fresh and snappy. That’s precisely what makes it both instantly gratifying and enduring some 40 years later. There’s no less integrity; the darkness is simply punctured by occasional rays of dazzling, multi-spectral light.

Of course, to pit one version of The Cure against another is to miss the point. Their lasting appeal owes everything to that double life, pivoting back and forth between crushing doom and uplifting whimsy; counteracting too much of one with a healthy dose of the other.

Time has come for The Head On The Door to be celebrated as the pop masterpiece it is. The Cure would go on to have more commercially successful albums, but The Head On The Door laid the foundations to transition from cult post-punk curios to bona fide – albeit awkward – pop stars.

It’s their take on a jukebox collection, showing them at their most inventive and eclectic, while remaining unmistakably The Cure. Not the “sell out” that some might profess it to be. It’s simply success on their own terms. Only The Cure could get away with an album with tracks so cute and cuddly with lyrics dealing with paralysis, death and turbulent nightmares; a delicious blend of childlike wonder and nihilism in one neat package.

The Songs

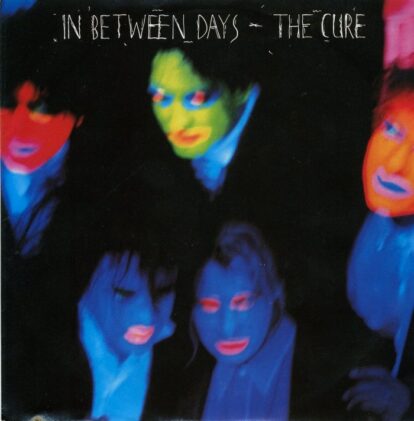

In Between Days

One of their most recognisable tracks, this is The Cure at their most breezy, uplifting and life-affirming. Though lyrically, it’s laced with a sense of yearning and regret of losing a love, it carries an overwhelming sense of optimism, as if, however bad it might feel right now, everything is going to be just fine. It’s partly this bittersweet, upbeat melancholy which has led to many New Order comparisons. It’s been covered a gazillion times, by everyone from Kim Wilde to Korn, but none can compete with the pure majesty of the original.

Kyoto Song

As alluded to in its title, Kyoto Song is a distinctly Eastern-inspired track, taking influence from the music of Japan, with the chiming riff and crashing drums. You can hear the Banshees influence, but it’s slower and more brooding, skulking along on a Gallup bassline, while maintaining a very clear finger on the pulse. While the production is slick, the lyrical imagery is harrowing: “A nightmare of you/ Of death in the pool/ Wakes me up at a quarter to three.” This is then juxtaposed with the chorus, proclaiming that “It looks good, it tastes like nothing on earth.” It mines that classic Smith ambiguity; you’re not quite sure of the morality of the narrator, but it’s thrilling nonetheless.

The Blood

The world music exoticism continues with an energetic flamenco work-out, complete with lightning fast, percussive, rhythmic acoustic guitars, snappy castanets, and shrill shrieks from Smith. The sounds conjure up the image of Smith walking down a dusty track in the midday sun, before stumbling into a tumbledown bar, straight out of a Spaghetti Western. Lyrically, it draws on Catholic imagery, as Smith is drawn to the iconography of the blood of Christ.

Six Different Ways

One of many showcases for The Cure’s secret weapon and new boy, Boris Williams. A deliciously jaunty track that trips and stumbles over itself with bouncy piano and a squiffy, unconventional time signature on the drums. The signature piano riff was actually lifted from the Banshees track, Swimming Horses, which Smith had co-written the previous year. Like Close To Me, it has one of those flute-like keyboard riffs straight out of a children’s TV theme. Then in comes that classic synth string line, a characteristic of The Cure. The production is exquisite, abounding with luscious ear candy, from the fairground piano swirls to the satisfying tom-tom fills. Again, it’s The Cure at their most whimsical and uplifting. An utter joy from start to finish.

Push

A total change in vibe and one of the best intros in The Cure’s canon. In anyone’s canon. Shimmering, jangly chorus-laden guitars dance up and down the fretboard, Gallup’s signature punchy bass sound pulses, then those thundering drums from Boris Williams kick in. Push is like the best bits of In Between Days, Just Like Heaven and Friday, I’m In Love melded together into an extended instrumental Cure megamix. In other words, it’s totally ace.

It’s almost a full two and a half minutes before Robert Smith finally shrieks “Go! Go! Go!” in sync with the instrumental hits, in exalted release. It’s the track with the greatest sense of momentum, and the most bombastic ‘rock’ song on the record. It’s tempting to think it takes a little inspiration from Bruce Springsteen’s widescreen guitar anthems on Born In The U.S.A. the year prior, though that’s perhaps not a comparison Smith would immediately welcome.

The Baby Screams

Opening with an electronically processed arpeggiated sound, the expectation is an proto-rave club banger. Then it launches into a nagging piano riff coated in delay, around a simple revolving four-chord progression, driven along by Gallup’s bassline and driving skittish drums. Smith wails (in the way that only Smith can wail) over a repetitive arrangement. Cue more abstract allusions to dreams in the lyrics, though with an ominous repeated line, commanding the listener to “strike me dead”.

Close To Me

That infectious beat. Those handclaps. That bassline, like the start of an old, long-lost Motown classic. Those claustrophobic, breathy vocals, stuttered out like an exotic percussion instrument. The plinky-plonky riff. The little flute riff. It’s so sparse, yet appetising; so taught and precise. The single version boasts that wonderful rasping horn section, though this isn’t present on the album version. Smith’s hushed vocalisations are pure ASMR. It’s a masterclass in minimalism and restraint.

A Night Like This

Next, a more conventional band sound; moodier, more akin to the atmosphere they would explore further later, on the majestic Disintegration. It has that weighty sense of foreboding and doom, but the drums keep it pushing forwards. A screaming sax solo courtesy of Ron Howe adds another dimension to the sound. Though it’s the most ‘meat and potatoes’ track on the album, compared to the razor-sharp sounds elsewhere, it’s a great song, and remains a live favourite. Its simplicity is its strength.

Screw

Again a total sonic shift from one song to the next. This penultimate track is built around an absolutely stonking fuzz-bass riff from Simon Gallup. Another cracking earworm, and the most aggressive track with an extreme-1980s urban street sound. Structurally, it’s the most underdeveloped track, and the shortest on the record too. All the taut, built-up tension of the verse never gets the release into a big poppy chorus that would push it over the edge. But that’s just nitpicking. As far as grooves go, it’s top-notch, and surely crying out to be sampled by Public Enemy for some hard-hitting hip-hop.

Sinking

A crashing piano sound echoes out into a slow, funky groove on the drums, built around a skulking chorus-laden bass riff from Gallup, a spacey, reverb-y piano motif, and then the big luscious, all-encompassing synth strings. As Smith utters the line “I am sinking”, devoid of all hope, oodles of delay repeat the phrase around and around over itself, like a swirling whirlpool. Then as he wails “I’ll never feel again”, it reaches a nerve-tingling climax. With its long, drawn-out intro, absolutely loaded with tension, this track essentially sets the template for Disintegration. Robert Smith obviously listened back to it and decided, “Yeah, that was great. Let’s do a whole album of that.” Five minutes of drawn-out doom. It’s effectively the soundtrack to the apocalypse; but somehow – it being The Cure – those crafty bastards manage to make the prospect sound so darn appealing.

For more on The Cure click here

Read More: The Cure – Wish

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.