Band mainstays invite Classic Pop for an exclusive chat about their upcoming tour and plans for a future ‘electropopumentary’

Glenn Gregory and Martyn Ware reveal all about their upcoming ‘electropopumentary’ project, new music, trying to work with Philip Oakey again and sneaking socialism into mega-selling albums.

In the living room of his garden flat in North London, Glenn Gregory has come to a decision. Sat at his coffee table, Martyn Ware with his feet up on a recliner next to him, Heaven 17’s singer leans into Classic Pop’s digital recorder and announces: “I’m committing this, on digital files. You’re the first to hear this, as this is me just coming up with it now: I’m committing to a new Heaven 17 album being finished within a year of this date.”

Let the records show it’s midday on 10 April 2025 when Heaven 17 confirm that their first album of new songs since 2005’s Before After really is happening. Probably. Martyn smiles at his bandmate’s enthusiasm, noting cautiously: “Glenn’s said this before. But we could do it.” Gregory won’t be deflected, insisting: “It needs to happen. Once you make your mind up to do it, you do it. Having a new Heaven 17 album is a good idea. “We should get it done quickly and not hang about.” Ware nods determinedly. It’s time for Heaven 17 to get going in the studio again.

The reason for their seemingly sudden enthusiasm to crack on is a new single, Something About You. CP had been tipped off the day before our interview that the single was ready. By the time we arrive at Gregory’s welcoming, pretty home – he’s lived here with wife Lindsay for 35 years, his studio in the sturdy garden shed – we’ve already played Something About You probably 10 times.

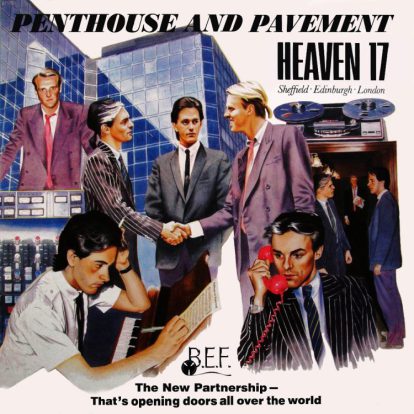

It’s exactly what you would hope Heaven 17 might sound like in 2025: Gregory remains unchanged since the Temptation days, the chorus’ claim “There’s always something about you living in my head” appropriate for such an addictive tune as the melody bounces along happily. Ware’s synths are sleek and modern, while maintaining the classic songwriting at Heaven 17’s core since their early Penthouse And Pavement days.

Image credit: ToddeVision

Beat Connection

The idea for new music emerged from chatting in their Manchester hotel the night before appearing on BBC Breakfast to promote their latest tour: surely they should have at least one new tune to play live? At the same time, Gregory had been playing around on a new drum machine, which recreates the original Linn model that Heaven 17 used when they formed.

“I programmed it and thought: ‘Oh, I like this beat!’,” the singer smiles. “It reminds me of the early phase of The Human League when the girls first joined, or us around Play To Win.”

The demo of that early Heaven 17 single was released in 2019 as part of their boxset of the same name. Hearing it again was Gregory’s unexpected highlight, as he recalls: “The demo of Play To Win is so funky, it’s like Prince. My son Louis and his mates listen to it. That demo is the vibe of Something About You, especially its guitar.”

Ware is as enthusiastic as his bandmate when he reflects on their 45 years in pop music. He says of the single: “I like everything about the song, but the chorus in particular is really catchy. Who writes catchy songs anymore? I thought we should do one.”

Within days, after years of studio silence, Something About You was ready. The reason for the wait isn’t that Heaven 17 are out of ideas, more that it’s harder to be motivated to take part in all the attendant self-promotion, as Ware explains: “We could make an album in a week and put it out online. The problem is then driving traffic to it, as you need a PR machine and marketing budget. Me and Glenn are of a similar thought: is all that admin something to devote our time to?”

Image credit: ToddeVision

Futurists To The Max

The pair are more certain about the value of touring. They’re passionate about playing live, still making up for lost time, as they didn’t tour until 1997. Futurists to the max, in the 80s Heaven 17 thought playing live was an old-fashioned notion suitable only for ghastly rock’n’roll squares.

They’d discuss it occasionally – Gregory remembers plans for a stage set based on West Side Story, a notion Ware considers: “Still a nice idea, that” – but were put off, as touring sounded like a chore.

Ware considers: “We were having a whale of a time in London. Did we really want to go down the road of our contemporaries like Simple Minds? We’d see them at Virgin occasionally, where they’d say: ‘We’re on a two-year cycle: a year of touring, a year of writing and recording.’ That sounded like hell on earth to me.”

Eventually, Heaven 17 were persuaded to play live by Erasure, who offered a support slot on an arena tour. Firm friends since Ware produced Erasure’s 1994 album I Say I Say I Say, they thought: ‘Why not?’ and, as Ware remembers: “The next thing you know, we’re onstage at Birmingham NEC, surrounded by a load of ‘We love Heaven 17!’ banners.”

The first warm-up show in Norwich for the Erasure tour had seen a pilgrimage from fans around the world, as Gregory grins: “We thought: ‘Oh! There’s a possibility this might just work.’ It was 17 years after we started, and it still surprises me that people come to see us.”

Ware adds: “That first show was so long after our first three albums, but those records mean so much to people. The ambition we had in making them was to be timeless. We couldn’t imagine anything more than 10 years into the future. Look at us now…”

Image credit: ToddeVision

Filming Fandom

Nearly 30 years on, Heaven 17 have become such road warriors that their new tour is an excuse to have filmmaker James Strong direct a documentary about what the band means to fans.

Gregory has a sideline in composing music for TV and films – he’s currently scoring the next series of Suranne Jones’ BBC1 drama Vigil. Strong is a friend of his neighbour and the singer composed music for the director’s early work before he went on to make smash ITV shows like Mr Bates Vs The Post Office and Broadchurch.

When Strong saw the final show of Heaven 17’s previous tour at Shepherd’s Bush Empire, he was so taken by the intensity of the relationship between fan and band that he wanted to capture it on film. Gregory reveals: “I told James we needed a reason to tour, like a 40th anniversary. Then I thought: ‘Unless we made the filming of it the reason for the gig…’. We want to capture what a Heaven 17 show is, that conversation between us and the fans.” Hence the new tour, Sound With Vision, in which Strong will follow the band and fans for a film to hopefully be released at the end of 2026.

Gregory and Ware enjoy hanging out with fans after soundcheck – “Those fans can tell others that we’re half-decent people, which spreads into the wider audience,” as Ware puts it – which led to a remarkable discovery for Heaven 17 themselves before a show in Frankfurt, where a rare but highly significant tape came to light…

Early Days

It’s part of Human League lore that, during their first incarnation with Ware and former Heaven 17 keyboardist Ian Craig Marsh, Gregory would have been their singer instead of Philip Oakey.

Instead, Gregory moved to London to become a photographer for NME and Sounds, shooting bands like The Rezillos, Madness and Darts. Gregory cheerfully confirms the story, but emphasises: “I’m really glad I wasn’t The Human League’s singer, because otherwise Phil might never have become Phil, and he did such a fantastic job. I love The Human League, both old and new. It was just luck that I didn’t stay.”

Gregory fronted just one show with The Human League founders Ware and Marsh, at Sheffield’s Psalter Lane Art College, where he’d studied photography. Calling themselves VDK And The Studs, the line-up also included Sheffield music scene staples Adi Newton of Clock DVA and Paul Bower of 2.3.

In Gregory’s memory, the gig was “fucking awesome, like The Velvet Underground: out there, chaotic. It was incredible.” Rumours persisted that this landmark show had been recorded, which Gregory would avidly follow.

Several decades and many false trails later, a fan approached Gregory after soundcheck in Frankfurt. Among other rarities, he produced a reel-to-reel cassette box, with “Studs” scrawled on the front. Gregory laughs: “I dragged him into the dressing room, yelling: ‘Martyn! Look what he’s got!’”

Two weeks later, Gregory received an MP3 of the show: “I was so excited. Then I listened to it. It’s dreadful.”

Ware nods: “It’s awful. It’s unlistenable. But it exists.”

British Electric Foundation

That show nonetheless proved key to the existence of The Human League, as Ware recounts: “It was a seminal day. After we played, a Manchester punk band, Drones, performed. They were even worse than The Studs. Then the headliners played, Slaughter And The Dogs, who were somehow even worse than Drones. At that point, I was on the cusp with The Human League, between taking it seriously or not. As I was watching Slaughter And The Dogs, I thought: ‘We can’t be any worse than this.’ That was the day I thought that maybe The Human League really could do it.”

Of course, after The Human League’s first two albums, Ware exited the band. Joined by Marsh, the pair formed British Electric Foundation (B.E.F.).

By coincidence, on the day of Ware’s departure, Gregory was back in Sheffield, to photograph a Joe Jackson gig for NME. Gregory glances over to Ware, still delighted at how Heaven 17 came into existence: “I called Martyn before the show, saying: ‘I’m in Sheffield. Fancy meeting up?’ Martyn was pissed off, going: ‘Yes, I fucking do!’ The timing was the weird synchronicity that always seems to happen to us.”

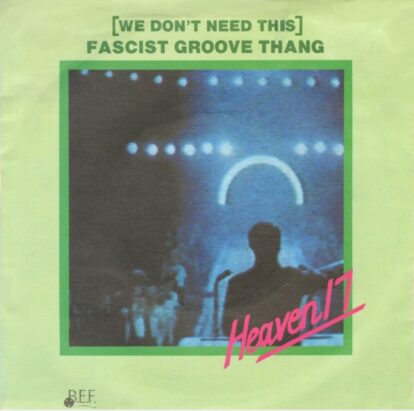

The pair proceeded to get ferociously drunk at The Red Lion pub next to Jackson’s gig at City Hall. Gregory never made it to the concert, instead planning with Ware to start a band and give up music photography to return to live in Sheffield. He says: “This was on a Friday. I returned to London on Saturday, came back to Sheffield on Monday. By the following Friday, we’d written and recorded Fascist Groove Thang.”

Anger Is An Energy

That Heaven 17 got off to such a monumental start was thanks to “the anger and energy flowing out of us,” according to Gregory, as Ware explains: “That anger can go to the dark side, where you become bitter and twisted, or you can redirect it into something positive.

“We’ve always been positive people. We came from thinking something like The Human League and Heaven 17 would never happen, so anything that did happen just seemed like a bonus.”

Musically, Fascist Groove Thang saw Gregory, Ware and Marsh remove The Human League’s manifesto of “Only synthetic sound”. There was even, gasp, a bass solo. Ware says: “All bets were off. That electronic manifesto had been inspired by Kraftwerk, but in Krautrock I also liked bands who were a hybrid of real and electronic instruments, like Can, Neu! and Amon Düül.”

Lyrically, Fascist Groove Thang was the first marker that Heaven 17 could tackle big subjects. “Phil had no interest in any of that political stuff,” states Ware. “He was into sci-fi and being profound. We wanted to shock people when they first heard us. In a minor way, Fascist Groove Thang is legendary, and that’s fantastic.”

Over 40 years on, its sentiments are still relevant, arguably more so given current world events. “It’s frustrating that it is still so relevant,” nods Gregory. “I think we could have released it every 10 years since, rewriting it with the name of Donald Trump or George Bush. That’s depressing.”

It wasn’t solely angry polemicism driving the trio, however, as Gregory admits: “We were afraid when we were writing songs like Let’s All Make A Bomb and At The Height Of The Fighting. Those threats were real, this wasn’t just a stance we were taking.” Ware adds: “We thought we might be blown up at any moment.”

Music Of Quality And Distinction

Perfectly formed on arrival as Heaven 17 were, they should have only been one side of Ware and Marsh’s production house. B.E.F.’s contract with Virgin stated that the pair could write and produce for six acts a year. They shouldn’t have even been part of Heaven 17’s line-up, as Gregory explains: “Heaven 17 should have just been me, getting a couple of other people in. But because me, Martyn and Ian were such good friends, Heaven 17 was instantly a very tight unit.”

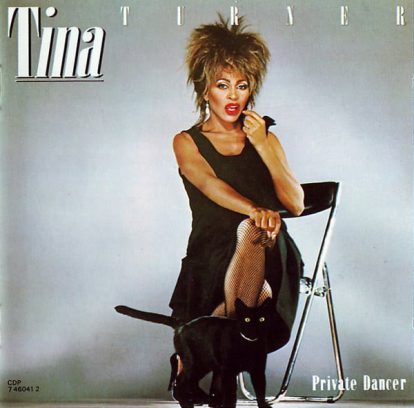

Names for other potential B.E.F. bands were floated – Monolith, Goggly Gogg Oil, The Word Masters – but no actual music. Instead, Ware and Marsh created the B.E.F. album Music Of Quality And Distinction, featuring singers who were deemed unlikely to be fronting cutting-edge club tracks.

It led to Ware working on Tina Turner’s artistic and commercial comeback in Private Dancer. But Ware points out: “We wanted the choice of B.E.F. singers to be transgressive.

“It was about respecting our influences, but also just to make people sit up and think: ‘Oh! That’s unusual!’

“Everyone thought Tina Turner was finished, the same with Sandie Shaw. It could have been Sandie who went on to sell 20 million albums. The key difference was, Tina’s label wanted to repackage her anyway. We sold Tina to a new audience, job done.”

A League Apart

The creative energy sparked by Fascist Groove Thang quickly led to Penthouse And Pavement. Its singles didn’t break the Top 40, but the album stayed in the chart for over a year. It had been made in the same studio while The Human League’s new line-up were recording Dare.

“That sounds apocryphal, but it’s true,” laughs Gregory. “We worked nights and The League worked days. We were on the 10pm-10am shift, but there were times when Phil would just stay in the studio at night. He had a bed upstairs, so he’d be asleep while we were recording Let’s All Make A Bomb.”

Ware frowns, telling Gregory: “Really? I never knew that! There was obviously an element of, ‘We’ll show you’ in our relationship with The Human League. There was a massive amount of resentment, converted into ambition, and we wanted to get our material out before them.”

Penthouse And Pavement was released in September 1981, a month before Dare.

However, the competition wasn’t wholly commercial, as Ware says: “We had an inkling that The Human League was going to be much more directly electronic pop.” The same manager, Bob Last, looked after both bands. Ware continues: “Phil became a popstar. Bob identified that in Phil and put a band around him, and it worked. To be honest, I was glad Dare did so well, as me and Ian were on 1% of its retail, which paid for my first flat in London.”

Mind The Gap

Last year, Oakey told CP that he and Ware had begun meeting up for lunch before the pandemic. Ware confirms any animosity has long since dissipated, smiling warmly: “I can’t help but love Phil. He was my best friend in my most formative years, from 17 to 21. The bitterness has died away, so it’s just fond memories now. I even thought maybe Phil might be interested in doing some more creative work, but that has never materialised.

“It’s great we had those lunches and we sometimes bump into each other at festivals, when it’s all very cordial.”

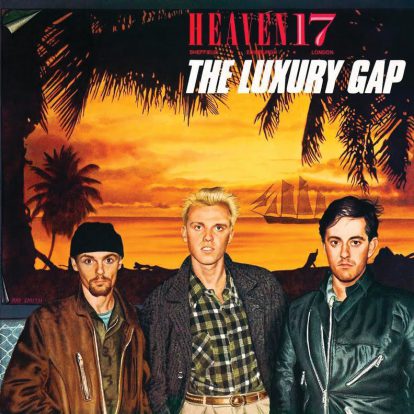

Despite the four singles from their debut failing to reach the upper echelon of the chart, Heaven 17 were certain they’d break through with their second LP and the pair credit Virgin for giving them the backing to make what they were determined would be a commercial smash. They wanted, in Ware’s words, “Classic pop songs, made at the best facilities,” in the case of The Luxury Gap George Martin’s AIR Studios. “Even writing the demos, Let Me Go and Come Live With Me felt huge,” insists Gregory. “I thought: ‘This is it!’”

Oddly, given Virgin’s general support, Heaven 17 only had one major row with their label: Virgin didn’t think Temptation was a single. On hearing the band’s version, it was instead sent to Joe Jackson’s producer, David Kershenbaum, to try to mix it into a single. “He totally flattened it out,” sighs Ware. “He added loads of delay and reverb, which lost the vibe completely. By that point, we were in Virgin’s offices, begging them: ‘Just trust us.’ It was blindingly obvious to us that our version was a stonking single.” He leans over into CP’s recorder, with a huge grin: “Anyway, they were wrong and we were right.” Gregory adds: “Temptation was a huge song, and this time we didn’t swear or mention Nazis.”

Art Versus Commerce

Temptation reached No.2 and was kept from claiming the top spot by Spandau Ballet’s True. “We were disappointed,” admits Gregory. “Temptation had been No.1 in the midweeks. We were doing a signing session in New York when we found out and that put a bit of a downer on signing stuff.”

Even though The Luxury Gap was designed to be commercially appealing, it found room for socialist anthem Crushed By The Wheels Of Industry as the album’s third Top 20 single. “It’s always worth trying to sneak in these things,” notes Gregory.

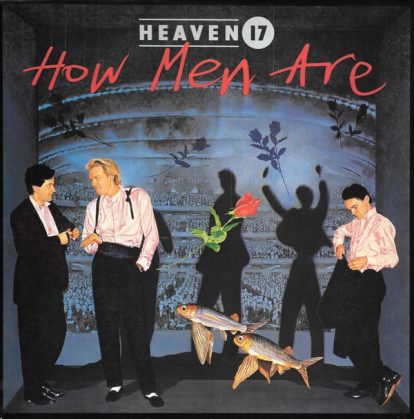

That Heaven 17’s third LP didn’t match The Luxury Gap in the chart is scandalous. As Ware points out, How Men Are is their equivalent of The Beach Boys’ Surf’s Up as their crowning glory. “Unless our third album went stratospheric, we thought it was our last chance to do a well-funded record,” says Ware. “How Men Are stands the test of time, it’s so unusual. I’m incredibly proud of it.”

An early album to be recorded wholly digitally, the 1984 LP cost £300,000 to make. “We didn’t recoup on it until the early 2000s,” notes Gregory. “We went out for a drink when it finally did recoup: blew the royalties on half-a-pint each.”

The trio went fully method, experimenting with sound techniques, with a roomful of technicians holding up spools of tape with pencils around the studio to loop the intro of And That’s No Lie, while Gregory ran on the spot in a vocal booth constructed from corrugated metal to sound out of breath on Five Minutes To Midnight.

“I was sweating in a weird metal box,” he summarises. “We messed around a lot, trying different ways of doing things.”

Let’s Make An Electropopumentary

Artistically, the results were worth it, but How Men Are stalled at No.12 and its three singles all missed the Top 20.

Subsequent albums, Pleasure One and Teddy Bear, Duke & Psycho, then both flopped. “We don’t often follow the easiest path for success,” says Gregory. “We’d rather take an interesting route.” Ware takes up the theme, adding: “And we can sleep at night. The only time we succumbed to commercial pressure from the record label was on those two albums, and they’re our least successful. We were losing confidence. Success ebbs away from you as soon as you want it too much.”

After an eight-year gap, Heaven 17 returned with 1996’s Bigger Than America. “That’s our massively underrated album,” Ware believes. “The message of that record is right on it for where the world is now. We also found our electronic core again.” In more of Heaven 17’s weird synchronicity, Bigger Than America was immediately followed by getting into playing live.

Hopefully, the film will showcase just how adept they’ve become at giving audiences a great time. Gregory and Ware discuss taking the film on tour, before Gregory eyes up the recorder one final time. “I want our film to be known as an electropopumentary,” he chuckles. “Oh, that’s good,” smiles Ware. “Can you float that in your article, please?” If it helps Heaven 17 to continue to take the interesting route, it’d be rude to say no.

For more on Heaven 17 click here

Featured image credit: ToddeVision

Read More: Top 40 80s pop artists

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.