The keytar king reflects on the joys of a good ‘woah-oh’ and synth-pop success

Celebrating both the 40th anniversary of Dream Into Action and the release of four albums in the past decade, Howard Jones continues to be one of music’s biggest explorers. Far from the earnest observer he’s sometimes portrayed as, the keytar king reflects on the joys of a good ‘woah-oh’ and how he swapped working in a cling film factory for synth-pop success.”

Around 10 years ago, Howard Jones made a promise to Classic Pop. He’d just turned 60 and was about to release Engage, his first album for six years. Over the next decade, Jones was determined to up his release schedule again. He would, he vowed, put out three more albums by his 70th birthday, to be titled Transform, Dialogue and Global Citizen.

Sure enough, the sparkling electronic pop of Transform and Dialogue have arrived. Jones might still be planning Global Citizen – it will, he says, be a collaborative album made with his musician friends across the world, its sound “a really eclectic mix” – but that fourth album in a decade arrived anyway, via Piano Composed, Jones’ third classical record. It was made after he discovered that Steinway had started making programmable pianos and, hey, wouldn’t thatbe a perfect blend of old and new musicianship to explore?

For someone in his seventies, Jones remains one of music’s great enthusiasts. Among his 80s peers, Jones was often painted as somewhat earnest; a vegetarian and Buddhist whose music was just a bit too serious next to the riotous colour of Duran Duran and Culture Club. Never mind that not eating animals and Eastern philosophy has become more in vogue now, there’s an easy line to be drawn from the emotional heft of hits such as Hide And Seek and Look Mama to current heartfelt singer-songwriters like Ed Sheeran, Dermot Kennedy and Lewis Capaldi taking residency at No.1.

More to the point, the stereotypical perma-frowning image of Jones is absolute nonsense. At his tour promoter’s anonymous office in central London, Jones spends 100 minutes laughing like a hyena on uppers as he details his unlikely fame, warm and fabulously self-aware about his stardom.

The common thread of his friends in music – Midge Ure, Phil Collins, Nick Beggs – is apparently their sense of humour. Asked how he and Collins bonded before him off of Genesis remixed No One Is To Blame into a hit and Jones instantly responds: “Phil is a really warm person who’d give you a big hug. He’s a great hugger, Phil Collins. He isn’t distant, and I really liked that about him.”

Image Credit: Simon Fowler

See The Summit

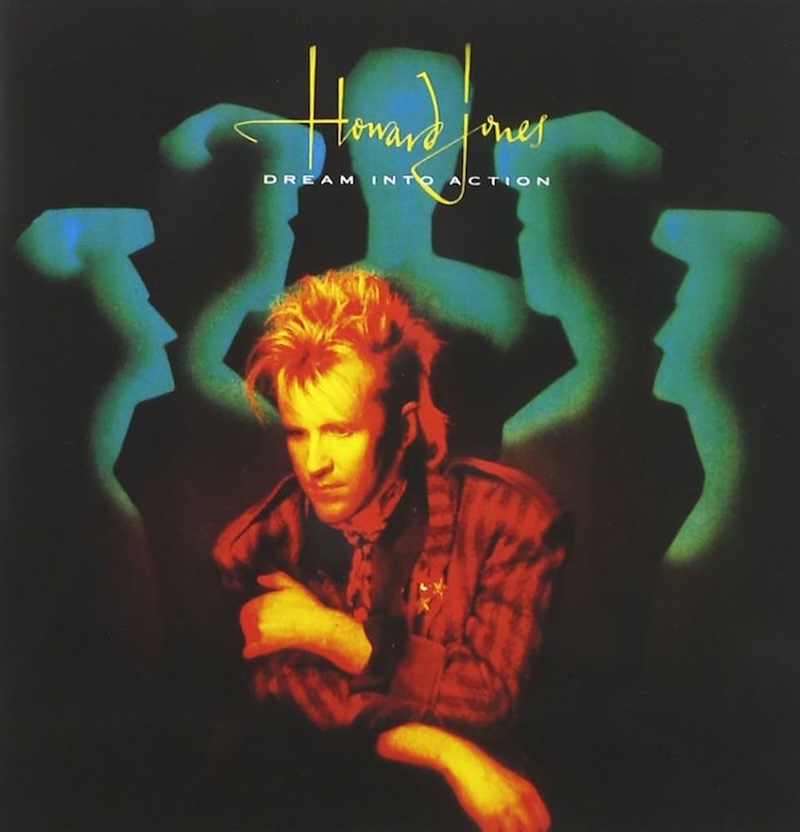

Jones is about to tour No One Is To Blame’s parent album, Dream Into Action, for its 40th anniversary. Unlike his chart-topping debut LP Human’s Lib, Jones’ second album just missed the No.1 spot… kept from the top by No Jacket Required and new pal Phil Collins. Any tension there? “No!” insists Jones, with another trademark scattergun laugh. “I was fine about that. No hugs lost.”

He’s honest enough to volunteer a different chart regret, though. “I never had a No.1 single in the UK, and I quite wanted one of those,” Jones confesses. “I wanted it to be Hide And Seek, but it was over-marketed.” His record label, Warner, gave away a free t-shirt with the 12” edition. “That was against the chart rules, so Hide And Seek got penalised. It would have been a lot higher if it hadn’t been knocked back.” He adds: “Anyway, that’s all history,” but it’s touching that it still rankles Jones a little, 41 years on.

That Jones is frustrated not to have a No.1 to his name is because, having become a popstar, he went all out to make great big pop singles. “I had no embarrassment about wanting to have singles,” he shrugs. “For me, being on the radio was the big thing. Plenty of artists sold lots of albums, but they didn’t connect with popular culture of the time, when that’s what carries you through and gives you longevity. Being on the radio while you’re doing housework or in the car, that’s when a song becomes part of your life.”

Given his determination to write hits, it was galling when Jones presented Dream Into Action to Warner, only to be told that they didn’t think it had any singles on it. “Looking back, that was a great strategy by the label,” reflects Jones. “I reckon that, in reality, they thought there was plenty of songs that they could release as singles. But they wanted me to give them more.”

It worked. “I panicked,” he admits. “As a reaction, I wrote Life In One Day that weekend.” It eventually became one of the four Top 20 singles lifted from the album. Jones is impressed by Warner’s testing of his ability to get a hit on demand, smiling: “Isn’t it great I got that song out of it all?”

Pressure Point

There’s an irony that Jones wrote Life In One Day while under pressure to have a hit. The song’s message is not to take life so seriously, to stop putting pressure on yourself and chill out occasionally. It was advice that Jones was offering himself, given how manic his career had become once Human’s Lib took off. “I was 28 when I got signed,” he explains. “It had taken me so long to get anywhere, I was worried I’d blow it and success would suddenly disappear. I had an anxiety that I didn’t need to feel. In general, I had a whale of a time, but imposter syndrome was something I always thought about.” There were positives to those worries, as Jones adds: “The anxiety helped me to keep it all going, to not just sit back.”

Wanting to continue his success helped Jones write a second album while promoting Human’s Lib. He would set up his 12-track portable Akai studio backstage in dressing rooms. “I had no songs,” he grimaces. “I panicked so much, thinking: ‘I’ve got to write songs!’” Yet, being an assiduous student of pop, the crowds’ reaction to Jones’ first headline tour fed into his new music. “I noticed that audiences love to sing along,” he says. “I thought I should build plenty of those moments into the writing. In that way, writing on the road was good for me, as there was so much energy around. Once I came off tour, I made the album pretty quickly, in about six weeks.”

The determination to give his fans a good singalong is amply demonstrated on Top 10 hit Things Can Only Get Better and its “Woah-oh-ohhh-woaah” chorus. “Yeah, I love the occasional ‘Woah-oh’,” acknowledges Jones. “As I say at my shows: ‘You don’t even have to know the lyrics to sing along to this one.’”

Canny popstar as he was, Jones wasn’t solely about mass singalongs. Is There A Difference? takes Buddhist philosopher Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching as its starting point for exploring humanity’s dual animalistic and human natures. The song is notably lacking in woahs. “I always want to promote self-determination,” reasons Jones of his motivation to write such a thorny song. “I want people to think a subject through, to see that you don’t have to follow what everyone else does.

“I didn’t want to write typical pop songs. I love them, but that was never my role. I’d studied Eastern philosophy and was interested in how to navigate being a human being. That’s still my main passion, so my music should reflect that.” He quotes the lyrics of New Song, his mission statement as well as his first hit: “I don’t want to be hip and cool, I don’t want to play by the rules, not under the thumb with the cynical few.” For Jones, that notion is what his lyrics have always espoused, as he explains: “Don’t have ideas forced upon you. What do you think?”

Fringe Benefits

Even in a decade packed with non-conformists, these knotty ideas being made explicit in his songs made Jones seem slightly apart from his peers. Did he feel like an outsider?

“I just wasn’t connected,” he agrees. “I’d watch Top Of The Pops and buy the same records everyone else was, but I wasn’t mates with everyone. On tour, I’d get invited to clubs and enjoy that, but it’s not my natural habitat. It’s not where I came from. I’d only recently been playing tiny gigs.”

Indeed, he had been. To rewind, Howard Jones’ itinerant childhood plays a large part in making him so single-minded.

His father, John, was variously an electrical engineer, lecturer and computer scientist: “Mainly brainy scientific stuff.” The Jones family moved 18 times before Howard was 18, including two 18-month spells in Canada. With a surname like Jones and spending some teenage years in Cardiff, he considers: “I feel pretty Welsh. I can’t speak Welsh, but I can sing in it and I cry at the national anthem when the rugby is on.”

Recalling how his family “yoyoed across the Atlantic”, the second time he left Canada for High Wycombe was the hardest of his 18 moves, as he remembers: “I had a girlfriend and was in my first band, starting to go to gigs. I loved Canada, then that life suddenly disappeared and I was on a boat back to England. It was: ‘Oh no, not again! I have to make friends again.’ That’s when music became my refuge.”

Although Jones started prog band Warrior in High Wycombe, he feels that becoming independent so young from constantly moving around helped ensure that he was destined to be a solo artist. “I love working with other people, but I want to be the prime mover,” he nods. “I like being in charge of the final output, of being able to say: ‘This is what represents me.’”

Although the small Bucks town’s music scene comprised just one pub, The Nag’s Head, by the early 80s Jones was building up a cult following, playing as a one-man band with a keyboard and drum machine.

“High Wycombe wasn’t the centre of any movement,” he grins. “I wasn’t exactly part of the New Romantics. I had to create my own gigs, phoning up pubs which didn’t normally put music on and taking that further afield.” Fans began following him: Jones recalls organising six coachloads to travel to famed London club The Marquee.

That’s the kind of genuine following record companies kill for, yet Jones reasons: “I didn’t fit in any mould, and labels couldn’t see past that. The doubters were: ‘It’s a one-man band with a mime artist onstage. You must be joking! What is this?’”

Image Credit: Simon Fowler

Silence Is Golden

Ah yes, the mime artist. An early fan of Jones, Jed Hoile was a college friend of the singer’s girlfriend, Jan. As Jones puts it: “Jed was dancing and loving the music when I played. Looking at the crowds, I thought: ‘He’s fantastic, and he should be up here with me.’ That was how Jed started, giving me another visual aspect.”

Eventually, Hoile became integral to Jones’ TV performances and videos. “Working with Jed was so much fun,” he beams. “We’d talk about how to represent the music visually. Because we’d already thought so much about the visuals, it meant I was ready for MTV. Those ideas weren’t expensive and there were moments, like Jed becoming a spirit taking on human form in Hunger For The Flesh, where the performances were sublime.” The two remain friends, with Hoile now running African drumming workshops.

Perhaps surprisingly, the first label to spot Jones’ potential was Stiff Records, more associated with boisterous mavericks such as The Damned, Madness, The Pogues and Ian Dury And The Blockheads. But their talent scout, Paul Conroy, had a row with Stiff boss Dave Robinson after a show at The Nag’s Head. According to Jones: “Paul told Dave: ‘We missed out on Depeche Mode, we can’t miss out on Howard Jones!’”

By then, Jones had improved his musical set-up after purchasing a high-end Jupiter 8 synth in dramatic circumstances. Working full-time at a cling film factory, Jones was also running a fruit and veg firm with Jan, who he’d met when he gave her piano lessons. Driving home one evening, they were hit by a drink-driver who had already crashed into four other cars before striking Jones’ delivery van.

“It was like a movie,” says Jones. “I wasn’t injured at all, but it felt like being in an explosion.”

Compensation money from a back injury Jan sustained in the crash paid for her boyfriend’s new synth. “We realised we could have died that night, so we thought: ‘Let’s not waste any more time. Let’s just completely go for it.’”

Around the same time, their beloved dog was hit by a car, and their van was stolen and driven into their small terraced house. “It all felt like a message,” believes Jones. “It was like we were being told: ‘Get on with this now and don’t worry about the future.’ Maybe success wouldn’t have happened without it all, because it was such a clear impetus. Within a year, I’d signed to Warner and New Song had reached No.3.”

Stiff scout Paul Conroy signed Jones as soon as he moved to Warner. Given his circuitous route to stardom, it was almost comedic that he was accused of being a manufactured industry plant once Human’s Lib took off. “I was the absolute opposite of being manufactured,” insists Jones. “Me and Jan had crafted all of it, down to my look.” Manufacturing a bloke pushing 30 and working in a cling film factory would have been a pretty wild move by Warner. “Exactly!” guffaws Jones. “When you get that misconception about you, you have to use it as something to fight against, to show people it’s not right. I’m still doing that! But it gives you a backbone because, whatever you come up against, you learn how to push through it.”

A Severed Alliance

One aspect Jones wasn’t wholly controlling early on in his career were his lyrics. Six of Human’s Lib’s songs are co-credited to one Bill Bryant. He introduced Jones to Buddhism and they were best man at each other’s weddings, but mentioning his name causes Jones to stumble over his words.

According to the scant information available online about Bryant, he hasn’t spoken to Jones since 1984.

Aside from an unsigned singer in 2012, Bryant appears not to have worked with any other musicians since. To say that Jones chooses his words carefully would be an understatement, as he eventually offers: “I don’t like to speak about Bill. I appreciate you asking, because I know it looks like: ‘Who is this Bill bloke?’ But it’s too nuanced and complicated to talk about. What happened would probably take a whole book to explain. When I finally get around to writing my autobiography, I will tell that story.”

One of Bryant’s lyrics, the title track of Human’s Lib, is the only song Jones now distances himself from, saying: “That song is of its time and the way a young man thinks. I don’t want to put those lyrics out there now. But I haven’t come across another song of mine that I’m not comfortable with or wouldn’t want to play.”

The intensity of Jones’ lyrics helped foster a close sense of community among his fanbase.

At his commercial peak, six people – including his and Jan’s parents – answered his fan mail. Of his rationale to respond to fans, Jones insists: “People who wrote to me relied on me to be honourable. We’d get letters from young people struggling with their parents. That is where Look Mama came from. It wasn’t my relationship with my mother, it was a theme that was coming through of young fans trying to get their own parental relationship right. That song was me saying: ‘I’m listening.’”

An even more lasting influence on fans came with Assault And Battery, the tough vegetarian anthem on Dream Into Action. “I’m very passionate about animals and not eating them, if you can avoid it,” he deadpans. “When you’re young, you’re militant about that. But as you grow older, you realise you have to be more flexible in your approach, because people think differently and there are different ways to live.”

Fan Support

Jones’ close relationship with his audience has continued throughout the subsequent 40 years. He even met several fans and wrote songs about them as part of a Pledge Music campaign, saying of the experience: “Empathising with the person in front of me, wondering how that would come out musically, I loved doing that.”

The fanbase were a practical help to Jones when he was dropped by Warner after fifth album In The Running in 1992. Jones stands by the album, citing Lift Me Up as “a cracking single”, but acknowledges: “MTV wouldn’t show the video. Because we were into the 90s, they didn’t want any 80s artists. They thought: ‘He’s had his time’, and that’s fair enough.”

Of being let go, Jones remembers: “I was devastated. I thought: ‘This is the end, I won’t be able to release any more records.’ I was very depressed.”

Luckily, the dawn of the internet allowed Jones to mobilise his fans. “It was fortunate timing, as otherwise I could have been all at sea. I could contact fans through this new technology and I was able to release my own records. The following album, Working In The Backroom, was full of ideas and energy.”

Jones’ label, Dtox, enjoyed success with dance collective dba, whose keyboardist Robbie Bronnimann still works closely with the singer. The pair briefly became writers for hire, most notably penning and producing Blue on Sugababes’ second album Angels With Dirty Faces in 2002. “Sugababes were such fun to work with,” enthuses Jones. “They were banging out ideas in the studio and their vocal performances were so good. They made Blue a great track, and our kids loved them.”

Having completed his prolific promise during his sixties, in the next decade Jones plans to write both his autobiography and a book on how Buddhism practically affects his life. He’s also thinking about writing a musical with his friend Brian Transeau, aka trance musician BT.

Jones’ new Steinway Spirio piano also continues to inspire new ideas. Having made the Piano Composed LP, he raves: “The Spirio comes with a library of the planet’s greatest piano players, so you can watch legends like George Gershwin play your piano. It’s been an education. As soon as I saw the Spirio, I was: ‘Ohhhh!’ I could imagine what I could do with it. You can programme it to do things you can’t physically do as just one pianist, like my song Five Pianos, which I’d have needed five pianos to play before.”

Imposter Syndrome

As an artist prone to imposter syndrome, playing late in the afternoon at Live Aid − sandwiched on the bill between Sting and Bryan Ferry − naturally left Jones feeling a little nervous. “It was easy to have imposter syndrome on that bill,” he recalls 40 years on. “There were so many legends and people I looked up to. Then there was little old me at the piano.” Instead, Jones was delighted when the audience joined in on the chorus of Hide And Seek. “That was the best feeling in the world,” he beams. “It was such an affirmation. “The nervousness of being there at all, then having 100,000 people singing with me, it doesn’t get any better. I remember that feeling in detail, I can still absolutely go back to that moment.”

Jones’ nerves were further assuaged when he happened to bump into David Bowie backstage: “Bowie knew who I was and that I’d done well in America, which was just wonderful.” He also befriended Paul and Linda McCartney, “We got on so well and had vegetarianism in common. Linda took a picture of me and Paul, and later sent a present for our firstborn. “The only odd moment was a TV interview with me, Phil Collins and Sting. That was weird and embarrassing, I still can’t watch it now.”

Alongside the release of Dream Into Action and performing at Live Aid, Jones’ sensational 1985 saw him play a cross-generational meeting of stars with Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock and his friend Thomas Dolby. Organisers of the 27th Annual Grammy Awards ceremony wanted to see old and new keyboard talents come together. “It was a brilliant idea,” enthuses Jones. “I don’t know if the Grammys realised they’d change people’s attitudes to technology, but that date changed a lot. Here were the legends of Herbie and Stevie with the new people in me and Tom, with all our keyboards and drum machines around us.

“Once we all started playing, people saw it was no big deal. They realised we can make great music, too. We weren’t going to destroy the world after all.”

Initially, Jones and Dolby were waiting in a London studio for Wonder to turn up, but he failed to show. “It became even better,” says Jones, “because we had to go to Stevie’s studio in Los Angeles. I got to hang out with Stevie Wonder, then it was just me and him jamming. That was absolutely a moment!” Jones says of the performance: “It looked great: me with my hair and keytar, Tom looking like a crazy Beethoven with his keyboard. “Stevie had always pioneered the use of new equipment, and the credibility he brought was beyond question.”

Image Credit: Simon Fowler

Under The Radar

Not surprisingly for a deep thinker like Howard Jones, he’s also been trying to constantly progress ways to challenge himself mentally this past decade. A big breakthrough came when a friend recently took Jones to watch his first baseball game. During a break in play, Jones was in his usual self-deprecating mode, when his friend stopped him and said: “You’re the bloke who doesn’t realise he’s Howard Jones.”

It’s a notion that’s made this already excitable musician become even more enthusiastic, as he reveals: “My danger is underplaying it all. I have the opposite of ego, as I’ll think I’m just a lucky bloke who slipped in under the radar. I’m not going to be suddenly walking around with a huge ego, but that comment has changed things. We are all equal, with infinite potential to do whatever we want. So now, I do occasionally remind myself that I’m Howard Jones!”

Howard Jones’ UK tour runs from 12-22 November. For tickets and further information click here

Featured Image Credit: Simon Fowler

Read More: Top 40 synth-pop songs

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.