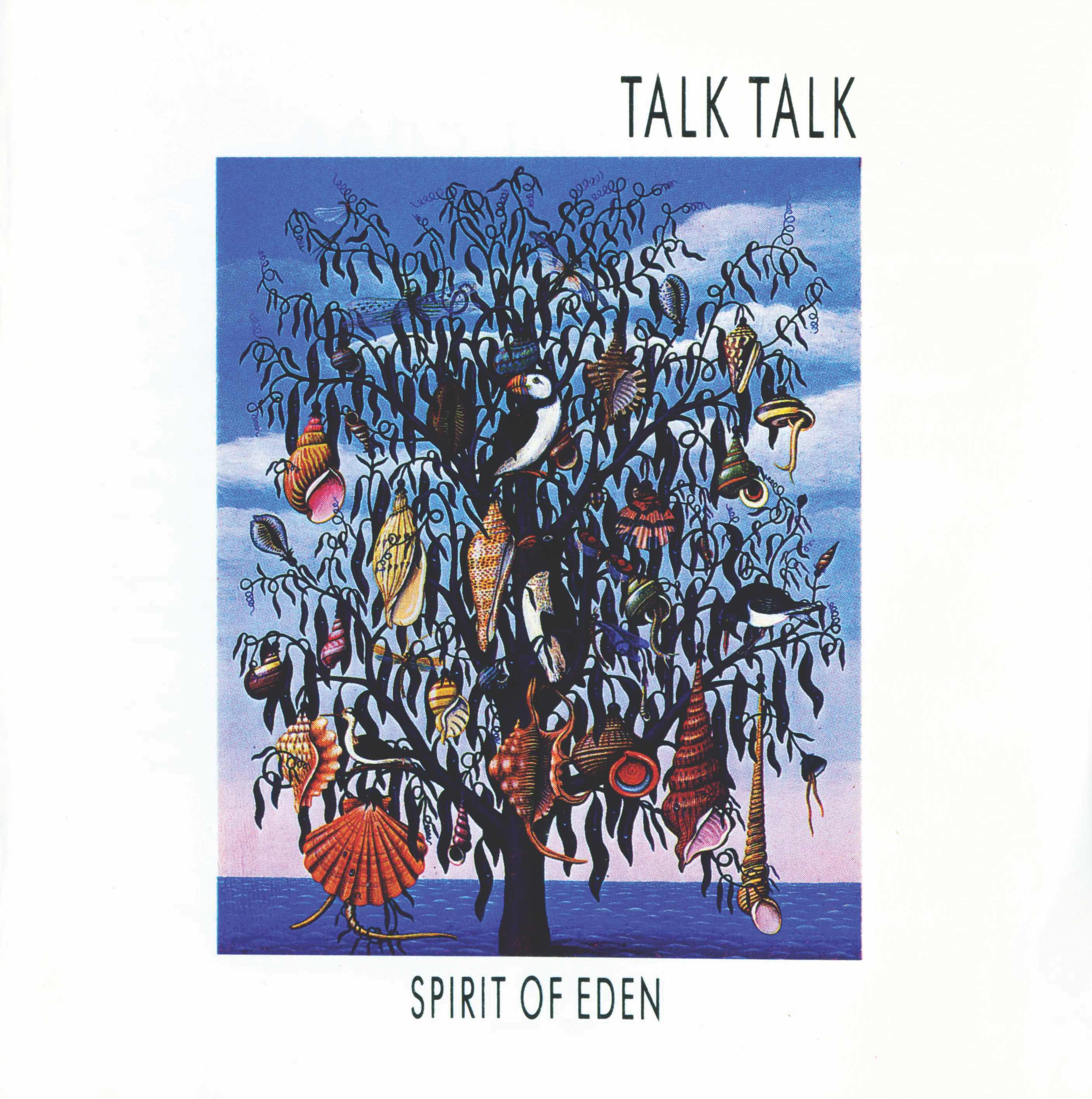

On its release in 1988, Talk Talk’s fourth LP Spirit Of Eden was spurned upon its release. These days, it’s considered an incomparable work of genius. By Wyndham Wallace

For most musicians, the first taste of success can be intoxicating – a heady incentive to pursue its commercial rewards with even more conviction. Talk Talk, though, reacted differently, both from most classic pop bands in the affluent 80s and, indeed, the majority before and since.

As their 10-year career advanced from their formation in 1981, they first slid gently, then swerved with increasing determination, towards the leftfield.

Leaving behind the radio-friendly pop of their early work in favour of an experimental, progressively more abstract sound, they alienated fans, baffled critics and, finally, ran out of steam.

But that’s because their goal, instead of fame, was more precious: “The freedom,” as frontman Mark Hollis put it in 1986, “to make a record exactly how we’d like.”

Spirit Of Eden, Talk Talk’s fourth album, in 1988, represented the point where Hollis, bassist Paul Webb, drummer Lee Harris and unofficial fourth member, co-producer and co-writer Tim Friese-Greene, took a last look at the promise of wealth and security that was theirs for the taking, and turned their back on it.

Instead of revelling with bikini-clad babes on yachts – like labelmates Duran Duran had with Rio four years earlier – they walked the plank and leapt into unknown waters.

More than three decades later, Spirit Of Eden is acknowledged as one of the most remarkable LPs ever made by a mainstream act.

Back then, however, it was an artistically startling but commercially suicidal move, and one that was – even to those closest to Talk Talk – unexpected.

Looking back, signs that they were dissatisfied with contemporary musical conventions were there from the start. As early as January 1982, in anticipation of their debut single, Mirror Man, Hollis told NME that his synth-pop group were “closer to a jazz quartet than a rock band”.

Six months on, he was berating journalists for comparing them to Duran Duran (with whom they shared a producer) rather than Otis Redding and John Coltrane. Nonetheless, as they stood on the brink of international stardom in the summer of 1986, no one anticipated the dramatic metamorphosis that was to come.

By then, Talk Talk had established themselves with their 1982 debut album, The Party’s Over, which charted in the UK at number 21, and its follow-up, 1984’s It’s My Life, which, though less successful in their homeland, boosted their profile across Europe and the US.

Enduring singles like It’s My Life and Such A Shame might not have set the British charts alight, but they’d earned the band a broad fanbase and they were now riding an ever-increasing wave of popularity on the back of a third album, 1986’s The Colour Of Spring.

Global hits Life’s What You Make It and Living In Another World had smoothed the transition they’d made from their early sound towards something more organic, and their live reputation had reached its zenith with two sold-out concerts at the Hammersmith Apollo and a legendary show at the Montreux Jazz Festival.

According to the band’s manager, Keith Aspden, signs that a radical change in direction was afoot only came in September 1986.

As the group flew back from Spain, where they’d played their biggest show to date, Hollis dropped what Aspden calls “the first bombshell: he didn’t want to play live any more”.

On top of this, “It became apparent that the success of The Colour Of Spring had given Mark and Tim” (who, by then, were the creative force behind the band) “the freedom and confidence to do whatever they wanted, without outside influence.”

What that meant was still far from clear. The Colour Of Spring had – in the shape of the fragile April 5th and the atmospheric Chameleon Day – merely hinted at Hollis and Friese-Greene’s inclinations to explore a more cerebral direction.

Additionally, Aspden’s belief that the album needed another single – which provoked Life’s What You Make It – had led to the jettisoning of It’s Getting Late In The Evening, a subdued, deeply moving track that foreshadowed what would follow but that was instead hidden on the B-side to Life’s…

So, as preparations began for their next album, the band’s label, EMI, readied themselves for a blockbuster follow-up that would break the US – and beyond – wide open.

Even Phill Brown, brought on board to engineer the album at Wessex Studios (where parts of The Colour Of Spring had been recorded), and who’d worked with David Bowie, Cat Stevens and Led Zeppelin, remained ignorant about what lay ahead.

“It must’ve been obvious to Tim and Mark that it was a different beast,” he says, “but I had no idea. It only became obvious to me during the first two months. I thought – like EMI – that we were recording The Colour Of Spring Part 2.”

Behind the closed doors of a former church hall in North London, Talk Talk bunkered down for the best part of a year, rarely breaking off from work except to sleep or eat.

No one entered the studio without invitation – and that applied to Aspden, who’d previously been involved enough not only to have insisted upon the inclusion of one of the songs that had earned the band their limitless budget, but even to have played bass recorder on …Spring’s final track, Happiness Is Easy.

Instead, Hollis and Friese- Green invited a parade of prestigious musicians to attend sessions – among them Danny Thompson, Robbie McIntosh and Nigel Kennedy.

These, Brown recalls, would record “eight takes” of their improvisations over one of the eight drum patterns that formed the foundations of the six tracks, before the best would be either mixed into the emerging tracks or erased.

Back in 1982, in a telling conversation with NME, Hollis had discussed A Clockwork Orange writer Anthony Burgess’ methodology.

“He said he can spend six hours writing thousands of words,” he’d admired, “and then throw almost all of them away. It’s the same with songwriting. It’s worth it for the stuff you’re left with at the end.”

“The band had made good money from The Colour Of Spring and touring, and wanted to experiment. It was purely ‘art’,” Brown states categorically of their meticulous working practices. “No one told the musicians what to play or even gave a hint of direction.

“Mark and Tim didn’t want to influence them, and wanted the ‘input’ from whichever musician was there at the time. There was no urgency because we had no time restraint or budget. The attitude was it took as long as it took to get the right result.”

Asked whether this might have been due to Hollis and Friese-Greene’s inability to articulate what they were looking for, Brown concedes, “I think we only knew what we liked once we heard it, plus we tried out every possibility until we stumbled on it.

“These would include which microphones to use, where to place the instrument in the room, what instrument it should be, what notes we should keep and their final location in the track. Once, we spent five 12-hour days perfecting a guitar sound! I know the album feels like seven guys playing live in a room, but every note is ‘placed’ where it is. The album is an illusion.”

Aspden first heard Spirit Of Eden after its completion. “Mark and Tim were pleased with what they’d achieved,” he recalls, “and were confident the album would be successful. Tim [who, according to Brown, believed the record sounded like a 1960s concept album] told me he thought it would sell at least four million copies.”

In the years since, Spirit Of Eden has come to be recognised as a masterwork – an influence on the likes of Radiohead and Elbow, and a precursor to what became known as post-rock.

Its free-spirited, free-form attitude, unfamiliar structures and unexpected bursts of both silence and discordancy make it a challenging listen, but it boasts an irrefutable, courageous grandeur that’s both emotionally breathtaking and intellectually thrilling.

Quite apart from Hollis’ peerless vocal performances, its arrangements overflow with unusual but enchanting sounds: harmonium, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, violin, even the choir of Chelmsford Cathedral.

Often compared to the work of Van Morrison, Miles Davis and Debussy – evidence of its disorientating artistry – the truth is it sounds like nothing else at all.

Legend has it that when Talk Talk’s A&R first heard the record, he cried – and not just at its beauty. Even Aspden concedes, “My immediate question was how would it be promoted with no live work or singles for radio. The market didn’t exist at the time for this record, no matter how brilliant it was.

“With just Mark and Tim involved, there was no balance, no perspective, no big picture. They took the reins and drove the coach and horses right off the cliff. When the album was delivered to EMI, the disappointment was apparent, and I could sense budgets being revised downwards as we listened.

“The reality and experience of producing a record ‘before its time’ is that nobody likes it when it’s most important.”

To Hollis, the experience was bewildering. The album, he insisted to Q at the time, was “only radical in the modern context. It’s not radical compared to what was happening 20 years ago. If we’d delivered this album to the record label 20 years ago, they wouldn’t have batted an eyelid.”

Inevitably, the band’s relationship with EMI soured. “They started messing me around by delaying scheduled advances,” Aspden explains, “saying they hadn’t actually expressed their satisfaction with the record. It could be seen as an attempt to bring us to heel. You can imagine how confident I felt in them.”

Aspden gave them the statutory three months to pick up the option for the next record, and an extra month just to make sure, before telling them they were too late. The subsequent battle went to the High Court. A month before Spirit Of Eden’s September 1988 release, EMI won the case, but Talk Talk’s appeal was successful the following May.

The band were released from the contract but, by this time, the six-month-old Spirit Of Eden was, as Aspden puts it, “dead in the water”. An album launch at the London Planetarium and a half-hearted attempt at a single release for an edited version of I Believe In You had already failed to make an impact, and reviews were mixed.

Many journalists were thrown by the artistic transformation the band had undergone, and even Q – who praised its “damn the consequences” attitude – conceded it was “the kind of LP that encourages marketing men to commit suicide”

“The euphoric high Mark and Tim had experienced after the release of The Colour Of Spring gave way to disillusionment,” Aspden admits regretfully. “They’d put their enthusiasm and belief into what they considered a masterpiece.

“Both secretive and introspective people displaying their art and souls for the first time in their lives, they’d had what they considered their finest work rejected and dismissed.

“The true cost was the destruction of the band. To add to the disaster, the record didn’t even recoup its recording costs. Spirit Of Eden was a sea of pain at the time. I’m just getting used to the new label of ‘masterpiece’. But I’m glad the album is being enjoyed more these days.”

In fact, more than three decades after its release, Spirit Of Eden is enjoyed more than it’s ever been, providing inspiration to all those who aspire first to great art rather than commercial success.

They may have obstinately turned their back on the very label that helped fund their creativity, and subsequently fallen apart after only one more album – 1991’s Laughing Stock – but their legacy continues, as Hollis once sang, to “rage on omnipotent”.

Talk Talk – Spirit Of Eden: the songs

1. The Rainbow

Opening with muffled strings and muted brass, The Rainbow sets out Talk Talk’s stall defiantly, its Eno-plays-chamber-music foundations laid confidently amid quiet whirring and ticking. Eventually, after over two minutes, a bold dobro chord rings out and a restrained beat shuffles in. But when a chorus materialises, it evaporates moments later like mist. Hollis’ distinctive voice barely rises above a whisper, even when he’s asking, “Well, how can that be fair at all?” It’s therefore a shock when, the song having collapsed in on itself after six minutes, a squealing, almost distorted harmonica solo breaks out, before Hollis brings things to another unforeseen close with the words, “Sound the victim’s song…”

2. Eden

Eden emerges from The Rainbow with the same solemnity with which the album began. Ten years later, Hollis would say, “Before you play two notes, learn how to play one note, and don’t play one note unless you’ve got a reason to play it.” Here, he tests that theory: as seemingly random sounds are teased out of a variety of instruments, a single guitar chord is strummed repeatedly until its strings threaten to snap. The crescendo is reflected in the build-up to the song’s climactic chorus, Hollis reaching for ever higher notes as he declares, “Everybody needs someone to live by.” Then he drifts towards silence once more, paradoxically intoning the words “rage on omnipotent”.

3. Desire

Much of Spirit Of Eden sports a spiritual quality, and Desire starts with the soft murmur of organs before the now-familiar sound of Harris’ minimalist percussion slowly swells, his drums rumbling ominously. The peace is suddenly broken when Desire bursts into a fury of disturbingly fierce Hammond organ, guitars and cowbell. Twenty seconds later, it’s over, the pastoral atmosphere regained, only to be shattered even more aggressively soon afterwards. Desire is Spirit Of Eden’s most unsettling – even shocking – song, seamed with tension and release.

4. Inheritance

After the storm of Desire, Inheritance opens with a bucolic sobriety, the gentle swish of lightly dusted cymbals and softly played piano chords backing Hollis’ impressionistic opening lyrics: “April song / Lilac glistening foal.” His tremulous vocals continue to deliver enigmatic instructions to, “Dress in gold’s surrendering gown,” while cor anglais, sundry other instruments and unidentifiable sounds tickle the fragile melody. The album’s shortest song – coming in at just under five-and-a-half minutes – Inheritance is perhaps the slightest of the collection’s six tracks, but it’s still impossibly haunting.

5. I Believe In You

A song of such exquisite elegance, it’s been known to make grown men weep, I Believe In You is full of organ swirls, chiming guitars and bewildering growls, all underpinned by a stripped-back bassline and simplistic 4/4 drumbeat. Hollis has never sounded more humbly melancholic than when he sings of how, “I’ve seen heroin for myself,” but the true magic happens when the choir of Chelmsford Cathedral appear like sunshine through clouds for the rapturously affecting chorus. Six minutes of religious ecstasy.

6. Wealth

The final comedown: elegiac, hymnal and passionate. Over little more than Hammond organ, plucked bass and gently strummed guitars, Hollis sings cryptic lyrics that seem to speak of love’s healing power and the willing sacrifices one should make to find it: “Take my freedom for giving me a sacred love.” Wealth brings the album to a mystical, sepulchral yet uplifting close, fading away to nothing over two minutes of delicious semi- ambience that leads us back – inevitably, emotionally – to the album’s beginning.

Talk Talk: Spirit Of Eden –

A Wealth of Anecdotes – Spirit Of Eden‘s Talk-Talking Points

- Inspired by a conversation about engineer Phill Brown’s experiences working with the band Traffic in November 1967, at London’s Olympic Studios, he and Mark Hollis chose to work only – as much as possible – with equipment built before then. Brown told Tape Op magazine that when they first went into the studio, “Mark said, ‘Let’s set this up as if it’s 1am in November 1967.’” Consequently, Spirit Of Eden was recorded almost entirely in the dark, “like a Sixties acid nightclub,” manager Keith Aspden says. “It was intense,” Brown adds, confirming details recorded in his recent book, Are We Still Rolling?. “There were oil projections on the walls and ceiling, and no other light apart from a strobe. I wouldn’t work in the dark again!”

- In order to prevent EMI from interfering with songs – as they had with edits for The Colour Of Spring campaign – drums constituted only one track in the final mix. “It was deemed that the only way you could stop the record company from remixing your track,” Brown explains, “was if all you put on there were things that were so decisive, they wouldn’t be able to make any changes.”

- When violinist Nigel Kennedy visited the studio to improvise his parts, the band were dissatisfied with his early attempts. After trying to dissuade him from performing in his traditional classical style, they finally bound the fingers of his right hand together with gaffer tape. “He played too fast and too many notes,” Aspden reveals the band later informed him, but he emphasises that, “Nigel was a really good sport and happily went along with it.” He ended up on the album.

- Included in the album’s credits is Hugh Davies, who provided “shozygs”. This was the name the composer – formerly Karlheinz Stockhausen’s personal assistant – gave the instruments he built out of household items. The name comes from his first invention, which was contained in the pages of an encyclopaedia between entries beginning with “Sho” and “Zyg”.

- None of the LP’s six songs retained their original working titles: Modell, Camel, Maureen, Norm, Snow In Berlin and Eric. The first three were initially included on the UK album as one single 23-minute suite, but the North American release was split instead into three tracks, with subsequent re-pressings following this practice.

- A video was made by Tim Pope for the edited version of I Believe In You. “I really feel that was a massive mistake,” Hollis later told Q magazine. “I thought that just by sitting there and listening and really thinking about what it was about, I could get that in my eyes. But you can’t do it. It just feels stupid. It was depressing and, to be honest, I wish I’d never done it. That’s what happens when you compromise.

-

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.