After starting life as one of many bands cynically marketed by record companies to cash in on the New Romantic scene, on third studio album The Colour Of Spring Talk Talk propelled themselves from synth-pop newcomers towards boldly experimental territory… By Neil Crossley

The outpouring of tributes following the sudden death of Mark Hollis in 2019 was notable for the sheer depth of respect shown to the Talk Talk founder and frontman by his contemporaries.

The outpouring of tributes following the sudden death of Mark Hollis in 2019 was notable for the sheer depth of respect shown to the Talk Talk founder and frontman by his contemporaries.

One of the most repeated and retweeted quotes in the hours and days following the 64-year-old’s death came from a 2012 interview with Guy Garvey in Mojo magazine, in which the Elbow frontman discussed Hollis’s enduring influence.

“Mark started from punk and by his own admission he had no musical ability,” said Garvey. “To go from having the urge, to writing some of the most timeless, intricate and original music ever is as impressive as the moon landings.”

It’s a sentiment reinforced by many. Over the course of five albums, Hollis would transform Talk Talk from an intriguing post-punk outfit to a band that created an extraordinary body of work, breathtakingly beautiful music with a spiritual power that could move listeners to their core.

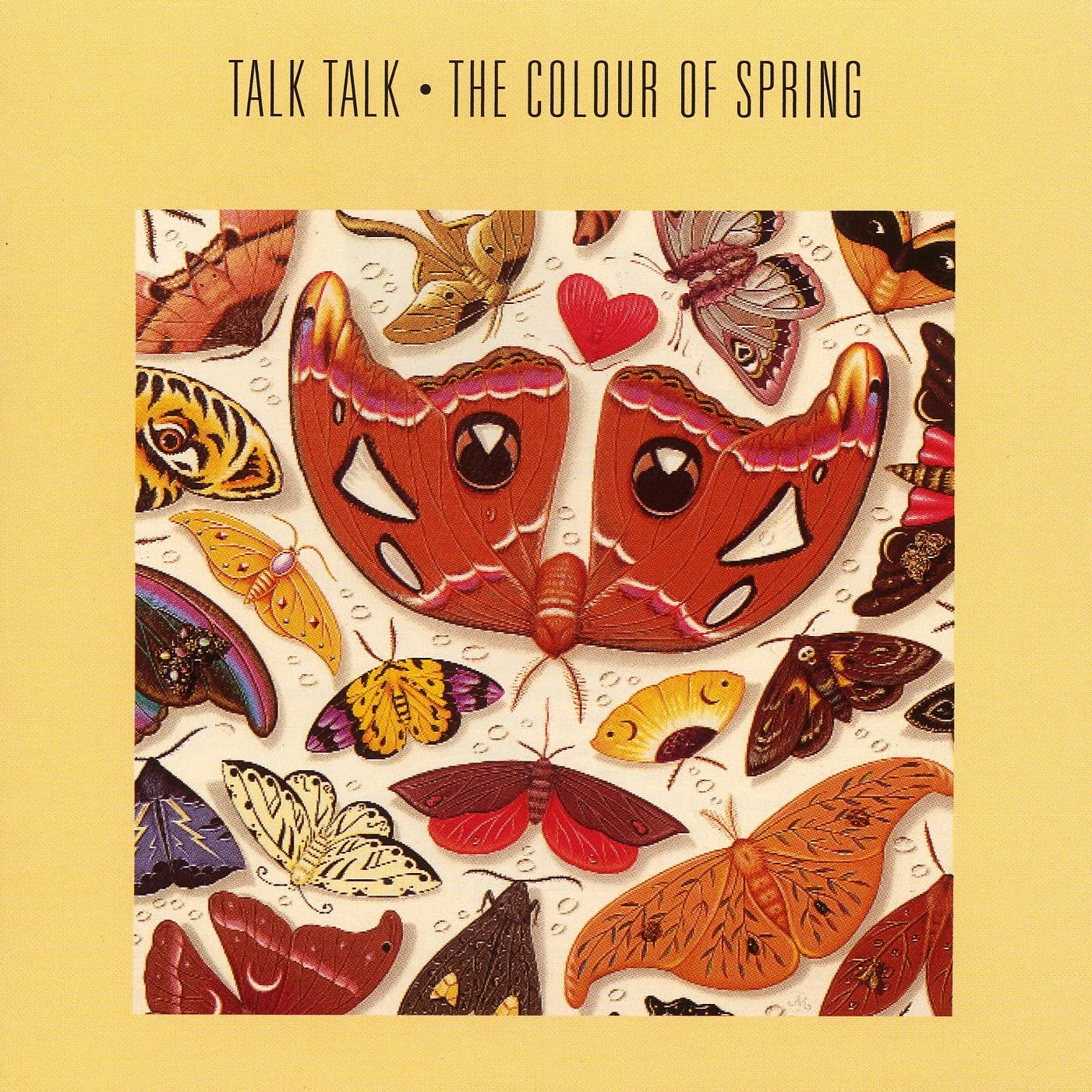

The first real signs of what Talk Talk were capable of came with their third studio album, The Colour Of Spring (1986), on which they wrenched themselves free from the constraints of 80s commercialism and pursued a stunningly creative course.

More than three decades on from its release, this ethereal and enigmatic album still resonates as strongly as the day that it was released.

From the outset, Mark Hollis’s musical touchstones were eclectic. Born in Tottenham, north London in 1955, he was heavily influenced by his elder brother Ed, a voracious collector of records who would go on to manage and produce Canvey Island pub rockers Eddie And The Hot Rods.

Ed Hollis guided his younger brother towards sounds that he otherwise may not have encountered, from free jazz and prog rock to American garage bands.

One record that had a pivotal impact on him was the 1972 US garage compilation album Nuggets, which prompted him to form his first band, The Reaction, in 1977.

Like many, he’d also been galvanised by the can-do DIY ethos of punk. “Up until punk, there’s no way I could have imagined I could get a record deal because I didn’t think I could play,” he told Jim Irvin in Rock’s Back Pages in 1998, “but punk said, ‘If you think you can play, you can play.’”

Mark and brother Ed co-wrote a single, Talk Talk Talk Talk, which appeared on the Streets compilation, credited to The Reaction. In June 1978, the band released the single I Can’t Resist, but in 1979 they split up.

Read more: Talk Talk – album by album

Spurred on by his brother, Mark wrote a new batch of songs and began forging a much broader sound. He put together a new band with keyboard player Simon Brenner, and two former members of Southend-based reggae outfit Eskalator, drummer Lee Harris and bassist Paul Webb.

Things moved quickly for the new unit. A demo recording found its way to Keith Aspden, A&R at EMI, who was so impressed that he left his job to manage them. EMI signed the band, now called Talk Talk, and set about trying to mould them into the next Duran Duran, one of the label’s major acts.

The initial plan for the band had been a piano, bass and drums trio, with Hollis on lead vocals. But the synth-heavy sound of the times inevitably crept in. EMI teamed them up with producer Colin Thurston, whose credits included David Bowie, The Human League and Duran Duran. The result was

Talk Talk’s 1982 debut album The Party’s Over, which yielded two singles, Mirror Man and a re-recorded version of Talk Talk. The record was a moderate success, reaching No.21 in the UK Albums Chart.

Despite the encouraging start, the band became increasingly appalled by EMI’s efforts to market them as part of the New Romantic movement. When Brenner let in 1983, they made no effort to replace him on keyboards, keen to distance themselves from the whole synth-pop genre. The band had tired, too, of plush publicity shots that had them kitted out in garish white silken box jackets.

“It gets tiring to listen to the Duran comparisons,” Hollis told Noise! magazine at the time. “I can’t hear it myself. I get depressed about the whole thing [because] kids ought to know about music, not image.”

In a concerted effort to shed their pop image and stretch themselves creatively, the band took a year out to record the album that would become It’s My Life (1984). At the same time, they rejected once and for all the image that EMI had foisted on them, abandoning the garish suits for donkey jackets, woolly hats and jeans.

They recruited producer and musician Tim Friese-Greene, which was to prove to be a key move in their development. Friese-Greene became the band’s de facto fourth member, their producer, keyboard player and, critically, Hollis’s principal songwriting partner.

His impact was immediate. It’s My Life was the sound of a band transforming from the time-locked limitations of synth-pop into more mature and sophisticated music.

Read more: Paul Webb interview

Lyrically, the focus was far more personal and emotive. And while synthesisers still dominated, the band were confident enough to introduce world-music rhythms and real, non-digital instruments into their sound, as well as animal noises recorded at London Zoo.

The songwriting was far more assured than their debut release. This was a cohesive album, with a collection of songs encapsulated within warm, gently seductive grooves.

It’s My Life produced three singles: Such A Shame, Dum Dum Girl and the title track, the latter going on to become the band’s biggest hit, as well as spawning a hit almost two decades later, for US band No Doubt.

The album also contained what was arguably the band’s finest recording to date, on the track Renée, a showcase for Hollis’s deeply soulful and melancholic vocals, a style defined by The Guardian as “full of pathos, restrained passion and a sense of struggle”.

The It’s My Life album reached Top Five in numerous European countries, but only reached No.35 in the UK charts. This was possibly due to the band’s decision to distance themselves from the mainstream market, a move amply demonstrated by their choice of video for the It’s My Life single.

Directed by Tim Pope and largely compiled from rushes from the David Attenborough-helmed BBC series Life On Earth, the video was rejected by EMI. The re-shot promo featured a dour-looking Mark Hollis declining to lip-sync to the backing track.

The recording sessions for the It’s My Life album also marked the beginning of an obsessively intense process of overdubbing, as Mike Oldfield’s bass player Phil Spalding found when he turned up for a session.

Talk Talk bassist Paul Webb was an exclusively fretless bass player, so Spalding was drafted in to play fretted bass on the track The Last Time. Spalding arrived at the sessions “disastrously hungover” and spent an entire afternoon and evening doing relentless retakes of the same bass part.

“We always had to go all around the houses to get next door,” explained Ian Curnow, session keyboard player on the album, “just in case there was anything that turned up on the other side.”

Buoyed by the creative success of It’s My Life, Hollis took a brave and radical decision: to banish synthesisers altogether from their next album and utilise only the natural sound and acoustic possibilities of traditional instruments such as piano, organ and guitar.

Read more: Making Talk Talk’s The Spirit Of Eden

The band took a year out to record the next album and a welter of session players were drafted in, such as Steve Winwood, guitarist Robbie McIntosh, bassist Danny Thompson and harmonica player Mark Feltham. The result would be a far more organic sound, with a sonic direction that would come to dominate their music from that point on.

Hollis and Friese-Greene spent the first four months of 1985 writing the songs, with the band then joining them in the studio to start laying down parts.

“At first, we were spending 12 hours a day, six days a week in the studio,” Hollis told the Glasgow Evening Times in February 1986, “then towards the end we gave ourselves the weekends off. Trying to stay fresh is the most difficult thing on such a long project.”

During recording, Hollis was listening to music by impressionist classical composers such as Satie, Debussy and Milhaud. Bartok in particular had a profound influence on the album. “Bartok’s string quartets… I’d never imagined something so beautiful existed,” he said. “Bartok has an impact on the arrangements on The Colour Of Spring.”

Instrumentally, acoustic piano and Hammond organ would prove the mainstay of the keyboard work on the album, with the highest-profile guest musician on the album, Steve Winwood, contributing some stunningly atmospheric parts on the Hammond.

Some more obscure instruments would also feature, such as the Variophon, an electronic instrument invented in 1975 by researchers at the University of Cologne. As the band worked on the album, they employed an eclectic range of keyboard instrumentation, such as Mellotron and melodica. But they resolutely drew the line at modern synth technology.

“In terms of the first two albums and the live field, synths are simply an economic measure,” Hollis told Electronics And Music Maker magazine in 1986. “Beyond that, I absolutely hate synthesisers… if they didn’t exist, I’d be delighted.”

It was a view reinforced by Friese-Greene, who was vehement on the subject of digital music technology. “To me, the idea of MIDI’ing up a piano is just plain sick. MIDI is a four-letter word, I can’t take it seriously at all. There’s really nothing printable I can say about it.”

In the year preceding the recording of The Colour Of Spring, Talk Talk spent nine months on tour. Hollis always highlighted the enjoyment that the band got from the “immediacy and excitement” of playing live. But he stressed that recording remained paramount.

“We’re not interested in dashing off a few tracks which will be forgotten in a couple of months,” he said. “When you’re trying to achieve subtlety and depth in what you do, it takes time…”

The Colour Of Spring was released in March 1986 to widespread critical acclaim from all corners. For those who had already written the band off as bandwagon jumpers and derivative synth-pop has-beens, it was an unexpected revelation.

Here was a genuine landmark release, ethereal and enigmatic with a haunting, fragile melancholy. Powerful, spacious rhythms combined with rich instrumental textures, all topped by Hollis’s pained and deeply moving vocals.

Talk Talk had created a sound that defied genres, drawing on jazz, classical, folk and pop, yet without ever falling into one distinct style.

The Colour Of Spring went on to become the band’s biggest-selling album, reaching No.8 in the UK charts. Life’s What You Make It, with its rolling piano riff, was the album’s sublime highlight, and became an international hit, expanding the band’s global fanbase and earning Talk Talk their third US hit single.

Commercially, The Colour Of Spring would prove to be Talk Talk’s most successful album, but for all its stellar achievements, their creative peak was yet to come. They would go on to release Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock, critically lauded works that many regard as their finest creative achievements.

Talk Talk disbanded in 1992 and Mark Hollis retired from music, choosing instead to live quietly with his wife and family in Wimbledon. Save for a self-titled debut album and a handful of appearances over the years, that’s precisely what he did.

In an interview in 1982, Hollis remarked that: “I want to write stuff that you’ll be able to listen to in 10 years’ time”. With The Colour Of Spring, and the two albums that followed, he produced a breathtaking body of work, one that will endure for a great deal longer than that.

Like all the best artists, Mark Hollis understood instinctively that what you leave out is often far more important than what you put in. “In some ways, I like silence more than I like sound,” he said. He also recognised that technical proficiency is overrated. “To me, feel is the most important thing, not technique. Take all that soul and gospel stuff; that’s got incredible feel, but it’s not necessarily good musicianship.”

Talk Talk – The Colour Of Spring: The Songs

Happiness Is Easy

A cool, spacious drum groove and skittering percussion intro this majestic, haunting opening track, before Danny Thompson’s distinctive double bass and warm lush piano chords glide into the mix. “Makes you feel much older/ Sublime the blind parade/ It wrecks me how they justify their acts,” implores Hollis, his strained, achingly poignant voice injecting a real pathos into the song.

As always, it’s the placement of space between the instruments that really elevates Talk Talk’s sound to a higher plane: a reverb-soaked conga one second, a high-end piano trill the next, always enhancing, never conflicting. All the album’s big-gun session players are on here: Steve Winwood on Hammond, Robbie McIntosh on guitar, Thompson on bass. A hugely emotive and inspirational opener.

I Don’t Believe In You

A troubled relationship appears to be the lyrical focus of this track, which features Hollis at his most poignant and plaintive. “Now the fun is over,” he begins. “Where do words begin/ I’m trying to find the path ahead/ Any way you say it/ The charade goes on.”

A slow, languorous groove harnesses a simple chord progression in the verse: Amin/G/Amin before building up through A/F/Emin/G towards the chorus. Bassist Paul Webb was always an integral feature of Talk Talk’s sound, creating strong melodic lines that would both anchor and inspire. Here, he provides a bass part of flawless taste and economy, while at 2:55 guitarist Robbie McIntosh unleashes some searing sustained notes that take the track to fresh heights.

Life’s What You Make It

“We always wanted to make a song that was based on a very simple piano riff and a subsequent tight drum part,” said Mark Hollis, speaking in 1986 about Life’s What You Make It, released as a single in 1985 to fuel interest in the album. The song was the last to be written, following concern from their management over the lack of an obvious single. While initially resistant, Hollis and Friese-Greene then approached it as a challenge.

“I had a drum pattern loosely inspired by Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill,” said Friese-Greene, “and Mark was playing Green Onions organ over the top.” Bold, pounding and dynamic, and enhanced by David Rhodes’ strident guitar hook, Life’s What You Make It is the soaring high point of the album. Animal sounds intro and outro the track. “They put nature into sound,” observed caughtbytheriver.net’s Robin Blunt, “emulating the ebb and flow of the natural world in their records.”

April 5th

A gentle smattering of tambourine, shaker and other percussive elements introduces this fragile minimalistic ballad, whose lyrics contain the album’s title phrase. A haunting piano motif roots the track, with natural stops and starts, over which Mark Hollis’s remarkable voice recounts the onset of a new season, personified as a woman. “Come gentle spring/ Come at winter’s end/ Gone is the pallor from a promise that’s nature’s gift,” he intones.

Not for the first time, the sound evokes elements of Van Morrison, as writer Graeme Thomson noted in The Guardian in 2017. “The gently decaying two-chord outro, a glorious tapestry of glistening piano, tenderly probing saxophone, acoustic guitar and stately organ, finds Hollis tripping over himself in a metaphysical trance,” he wrote.

Living In Another World

It’s wholly fitting that Steve Winwood is at the helm of the Hammond organ on this track, as there’s more than a hint of the warm, organic and pastoral strains of Traffic on this strident seven-minute sonic tour de force. The track gallops along from the outset, with Paul Webb’s bass only entering the mix at 0:52 on the Bmin to G shift, instantly elevating the track with its strong melodic line and flawless feel.

In an interview with Italian television in 1987, Hollis explained that the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre inspired the lyrics of this track. One musician for whom it holds relentless allure is Scottish singer-songwriter Kenny Anderson, aka King Creosote. “I never tire of [the song],” he said in the 2012 book Spirit Of Talk Talk: “and yet I don’t quite understand how they managed to make it sound like a musical version of that famous MC Escher staircase.”

Give It Up

Hollis was inspired by the modal jazz of Miles Davis, and it’s an influence that can be heard on this track. Producer Tim Friese-Greene provides the prevailing Hammond organ part and, once again, Paul Webb’s bassline brings a hook-laden melody that underpins the top line while driving the song forward. David Rhodes contributes growling, gutteral guitar sweeps at 3:22 while Hollis delivers the lyrics with utter conviction. “From the place that I stand/ To the land that is openly free/ Watching rivers run black/ By the trees that are vacant to greed.”

Chameleon Day

Béla Bartok is the principle influence behind the short, sparse instrumental piece that introduces Chameleon Day. Bartok was one of the impressionistic classical composers that Hollis was listening to during the making of The Colour Of Spring. “Breathe on me, eclipse my mind/ It’s in some kind of disarray,” sings Hollis in a voice of immense intimacy and purity. The track features the Variophon, an electronic wind instrument invented in 1975 by researchers at the University of Cologne.

Time It’s Time

By the release of The Colour Of Spring, all traces of Talk Talk’s synth-pop past were gone, replaced by strong influences of Traffic, Debussy and Satie. The warmth of the Hammond organ, acoustic piano, acoustic guitar and a whole range of quirky instruments such as Mellotron and melodica predominate. The pastoral themes of The Colour Of Spring are all pervasive on this final track. Hollis’s lyrics, as ever, are both deeply poignant and enigmatic. “Nobody knows how long/ Rustling leaves unrhyme/ Lullaby breeze unsung/ Babel of dreams.” As is often the case with Talk Talk, the modal shifts reach ever upwards.

Read more: Making Japan’s Tin Drum

The Players

MARK HOLLIS

The enigmatic, much-missed frontman of Talk Talk who passed away in February 2019 started his music career in punk rock outfit The Reaction. The Tottenham-born singer, the younger brother of Eddie And The Hot Rods’ manager Ed Hollis, was the guiding light behind transforming Talk Talk from a synth-pop group into an experimental art-pop outfit. After Talk Talk split, he released just one solo album, a hushed, skeletal eponymous LP in 1998. His last released music was a short instrumental in 2012, recorded several years earlier, for Kelsey Grammer’s post-Frasier TV show Boss.

TIM FRIESE-GREENE

Latterly becoming Hollis’ right-hand man in Talk Talk, Friese-Greene was the producer behind Tight Fit’s The Lion Sleeps Tonight. While never an official member of Talk Talk, he was a key component as producer, co-writer and performer from 1984’s It’s My Life onwards.

A tinnitus sufferer, he currently records under the name Heligoland. His last released work was the One Girl Among Many EP in 2015. The shadow of Talk Talk, though, has loomed large since the band split following their Laughing Stock LP. “After Spirit Of Eden, I found it really difficult to find anything that I found challenging enough,” he once said.

PAUL WEBB

Since Talk Talk’s demise, Webb and drummer Lee Harris have released two albums of world music-influenced improvisations under the .O.rang moniker. Webb has also released music under the name Rustin Man, first with Portishead’s Beth Gibbons on 2002’s Out Of Season, and more recently with his 2019 solo LP, Drift Code and its follow-up, Clockdust.

LEE HARRIS

Harris has worked alongside Webb in .O.rang, and drummed on Beth Gibbons and Rustin Man’s Out Of Season and Drift Code albums. He also made an appearance on Norwegian band Midnight Choir’s Waiting For The Bricks To Fall (2003) and ///Codename: Dustsucker by Bark Psychosis in 2004.

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.