The Associates – Sulk

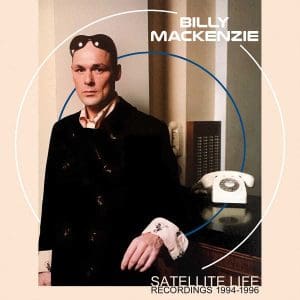

Revisiting the golden moment when Billy Mackenzie somehow became commercial, and the troubled music of his final years

The correct example for the most unlikely band ever to go mainstream, and showing why the early 80s was a time when literally anybody could be a star, is The Associates. Some people cite Japan, which overlooks what an unfathomably beautiful band they were. Others claim Talk Talk, as if they didn’t faff about making regular sub-Duran pop like everyone else before discovering free-jazz and not talking to anyone.

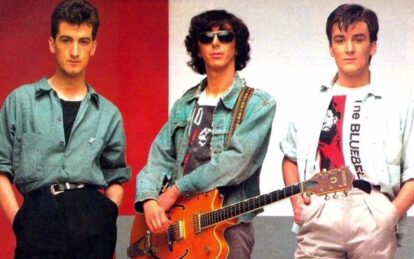

Post-punk in the sense they arrived after punk and shared its ethos that anyone could start a band, there had been glimmers of majesty on 1980’s debut album The Affectionate Punch and its associated singles, but it still seems an incredible gamble of Warner’s to sign The Associates; less so on the basis that the band’s new demos consisted of Party Fears Two and Club Country.

Those are two of the greatest singles ever made, but do they sound like hits? No, unless they were released in 1982. Thankfully, that’s exactly when they arrived, so of course operatic melodramas about social anxiety and mental illness scurried up the charts.

The large budget for Sulk and larger studio hijinks this resulted in are the stuff of 80s music industry legend but, although the band collapsed almost immediately after Mike Hedges finished recording, during those months in Camden there was also focus among the drugs and pissing in guitars.

Bookended by the flighty, mischievous instrumentals Arrogance Gave Him Up and Nothinginsomethingparticular,

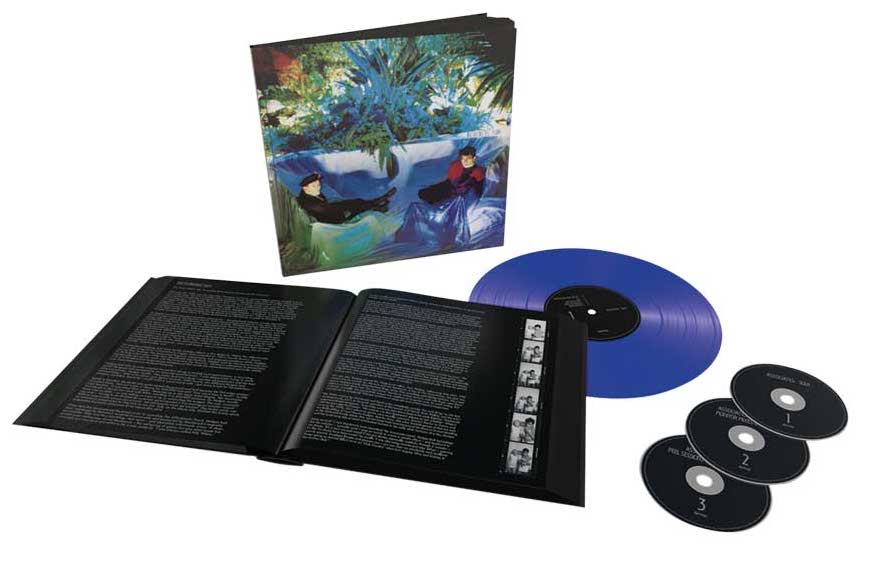

it’s typical that the poppiest melodies aside from its singles don’t feature Billy Mackenzie’s uniquely multi-ranged and adjective-devouring voice, though the latter soon transformed into standalone hit 18 Carat Love Affair, included on this 40th anniversary reissue.

More than virtually any other album, Sulk is its own world, Mackenzie’s cryptic lyrics and invariably perfectly judged voice the ideal unreliable narrator for noirish mysteries like Nude Spoons and Skipping, where Michael Dempsey and John Murphy’s undervalued rhythm section anchors the listener, only for Alan Rankine’s flourishes to pull the rug from under the unwary. Decades on, there are still layers to the skittish Bap De La Bap to be uncovered.

As with 1981’s Fourth Drawer Down compilation of the bewildering array of releases following The Affectionate Punch, even a major label couldn’t sensibly collate The Associates’ creativity. Thankfully, BMG have now mostly corralled the standalone songs like Love Hangover and John Leckie-produced Australia which offered more straight-ahead pop than their parent album.

Among the half-dozen other tracks, Ulcragyceptimol stands out as a seeming vocal blueprint for Mackenzie’s occasional pal Morrissey. Both Peel Sessions and a handful of demos are here, too, though annoyingly six previously released mixes are now missing, notably the wondrous 12″ of Club Country, a mistake in not finally making Sulk definitive.

Still, the new edition at last gives an official release to the closest Sulk came to a concert: a widely bootlegged 10-song Dutch radio session, sounding surprisingly regular with its more instantly recognisable rockist energy.

Rankine left four months after Sulk was released, so one of the all-time great art-pop albums was never toured. None of the band ever matched its heights again: there’s no shame in not living up to perfection, and hopefully Sulk will usher in reissues of other Associates albums: 1988’s The Glamour Chase and 1990’s Wild And Lonely especially need some love as well as a competent cataloguer.

Meanwhile, Cherry Red have commendably at least tried to make sense of Mackenzie’s final work. The dozens of recordings he made in his final two years have previously been issued posthumously as the albums Beyond The Sun, Eurocentric, Auchtermatic and Transmission Impossible.

Copyright reasons mean a handful of collaborations with Loom and Yello’s Boris Blank are missing, but Satellite Life is a decent 39-song round-up of a singer increasingly drawn to torch songs. By his standards, the acoustic Blue It Is and piano lament And This She Knows are traditional ballads.

There are still experiments recalling his early sonic adventurousness: Hornophobic and 14th Century Nightlife are Mackenzie having a high old time going jungle; Sour Jewel sees him succumb to Britpop.

Mackenzie was beautiful singing cabaret, but he was beautiful singing anything. It’s 25 years since his death and there’s never been anyone like him. How incredibly lucky we were to have Billy Mackenzie at all.

★★★★★

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.