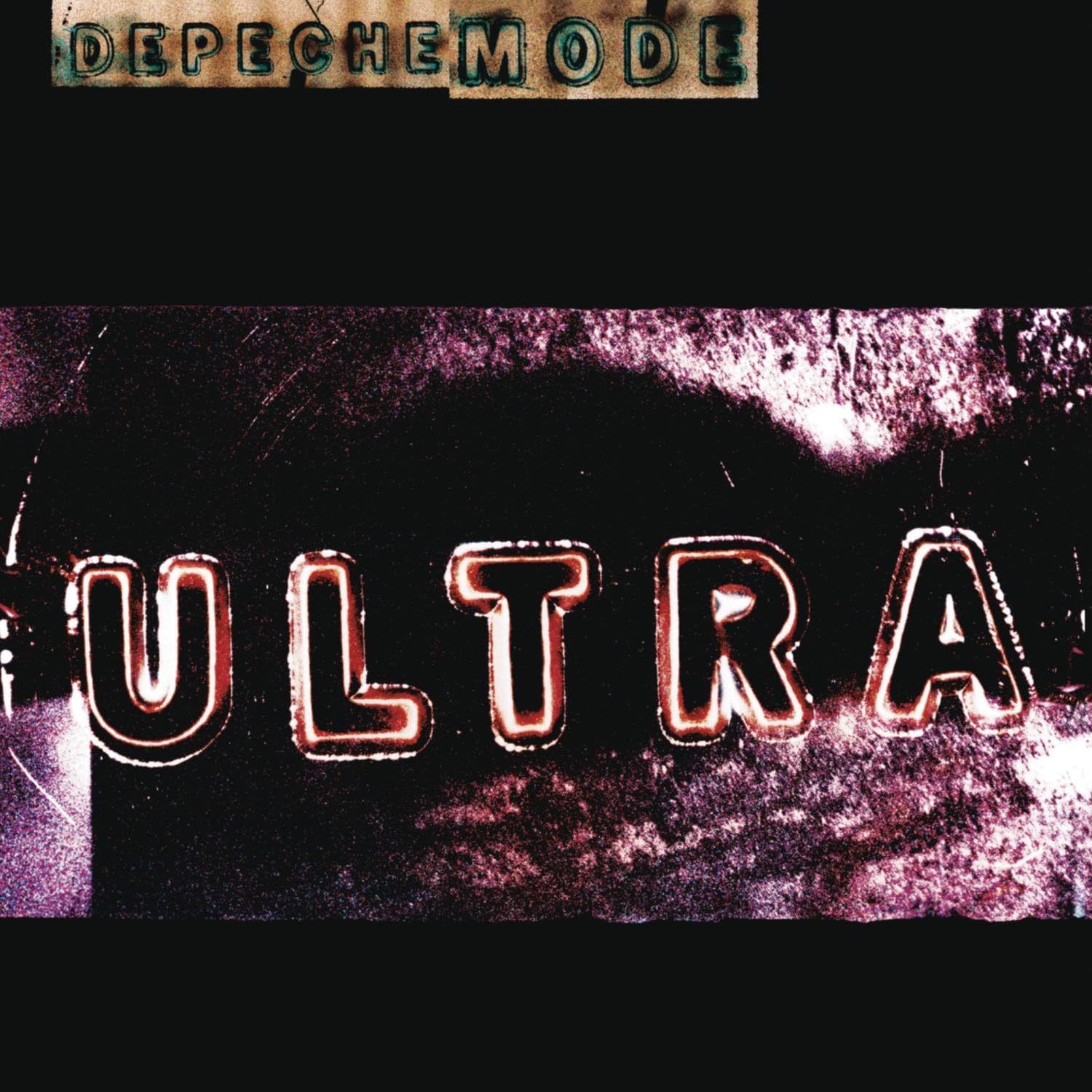

Depeche Mode Ultra cover

That the ninth album by Depeche Mode, Ultra, exists is somewhat of a miracle given the strife that surrounded its making but the result was one of the band’s best…

Ultra was an album of firsts. The first album to be made after the departure of Alan Wilder, the first album the group had recorded as a trio since A Broken Frame 15 years earlier and the first album not to have any band members involved in its production.

Instead, dance music maven Tim Simenon of Bomb The Bass fame was the man at the mixing desk (Gore and Gahan were fans of an album Simenon had worked on, the 1995 release Shag Tobacco, by ex-Virgin Prunes frontman Gavin Friday).

In many ways, it’s astounding that Ultra was even finished, given the dramas that surrounded its making (it’s notable that a documentary that accompanied a 10th anniversary edition of Ultra was titled Oh Well, That’s The End Of The Band…).

It took over a year to record, during which time Dave Gahan’s brutal heroin addiction had gotten so out of control that he’d overdosed on a combination of cocaine and heroin and very nearly died.

The singer entered rehab in mid-1996, halfway through recording, returning to the studio to wax the vocals for lead-off single Barrel Of A Gun.

The song was the first taste the public had of the post-Wilder Mode. “It’s about understanding what you’re about and realising that you don’t necessarily fit into somebody else’s scheme of things,” said Martin Gore, who was certainly influenced by what was going on in Gahan’s life during its composition.

Gahan, meanwhile, said of the track: “The song sums up the way I was treating myself and everybody around me. That’s what life had in store for me every day. It’s a really powerful statement. When you’re in that kind of row, the last thing on your mind is dying.”

Barrel Of A Gun’s fiery rhythms were a confident statement of intent, sending the single to No.4 in the UK. Its stellar chart placing even prompted the band to say yes to a by then rare Top Of The Pops appearance, featuring Tim Simenon on keyboards and – somewhat surprisingly – regular photographer Anton Corbijn on drums.

More low-key and melancholic than the industrial rock-powered Songs Of Faith And Devotion, Depeche Mode’s ninth studio album found the newly-configured trio rediscovering the synth-driven sound that had propelled them to fame, with more personal, introspective lyrics, from the fragility of relationships (It’s No Good) to alienation (Sister Of Night) to belief (The Love Thieves).

Musically, the album was an evolution for the band. Wilder’s absence and the hiring of Simenon certainly expanded the record’s sonic palette, with echoes of German 70s electronica and hints of trip-hop in the woozy, haunting Sister Of Night.

Daniel Miller believes that the album’s aural starkness was a direct result of the new set-up. “I think that’s Tim’s influence and Al not being there,” he said in Depeche Mode: A Biography.

“Alan liked big arrangements, strings, choirs, dramatic piano things and I think Tim was trying to lay bare Martin’s songs by making things more minimal and emotionally raw.”

Ultra finally arrived on 14 April 1997, going straight in at No.1 in the UK, selling over 40,000 copies on its first week of release.

Three more singles were released from the record – the lounge-y It’s No Good (UK No.5), the string-enhanced ballad Home (UK No.23) and a shortened version of Useless (remixed by Alan Moulder).

The video for Useless would be directed by long-time collaborator Anton Corbijn, his last promo for the band until 2005’s Suffer Well.

The press campaign for Ultra was dominated by revelations of Dave Gahan’s drug addiction and near-death experience.

And while the singer had been initially keen to share his story, every publication thereafter questioned him about it and, in the end, those lurid headlines threatened to eclipse the album itself.

Despite Ultra’s reputation now as one of Depeche Mode’s greats, it’s clear that Gahan’s almost pathological honesty was affecting how critics were interpreting the album, with many of those initial reviews finding the songs too bleak and its production too bare.

“If these songs are about Gahan’s decline as seen through Gore’s eyes, then they’re written in such blank and generalised terms as to be almost worthless as insights into his condition,” wrote the NME, adding, “it’s all too clinical – issues are skirted, poetry is attempted and we’re left clutching another instalment of stadium-orientated angst, at a time when we were expecting reflective intimacy.”

- Read more: Top 40 Depeche Mode songs

Not all the reviews were so damning. Jim Farber in a review for Entertainment Weekly commented: “Ultra, their first work in four years, combines up-to-the-second synth effects with rippling melodies – all supported by the grim sonic architecture that long ago made DM the darlings of many a sour teen. Imposing spires of synths, industrial rivets of percussion, churchy organs, and grave vocals erect an edifice of reverent dread.”

The Guardian, meanwhile, described Ultra as “dark even by [Depeche Mode’s] standards”, and on its songs, remarked that “anyone doubting the potency of pop music should hear these, then pretend they’re unshaken.”

Greg Kot of The Chicago Tribune even stated that the album “ranks with their best work … this British combo has made a disc that should please their millions of followers.”

Fletch was convinced the generally negative reaction to the record was a result of the ‘Gahan thingy’ as he put it. Gore agreed, saying, “The press we’ve received around this album isn’t going to attract anyone.”

One person who found Ultra a difficult listen was Alan Wilder, who commented: “I can’t hear it in the same way as a record I was involved with, but I certainly don’t feel a yearning to be involved again, and I’ve no regrets about leaving at all.

“The album is difficult for me to comment on, though I do have something of a stock answer, which is: you can probably work out what I think about it by listening to Unsound Methods and then Ultra, because the two records tell you everything you need to know about what the musical relationship was between myself and Martin.

“It’s almost as if we’ve gone to the two extremes of what we were when we were together. What the band had before was a combination of those extremes.”

Twenty-six years on from its release, Ultra is now considered a highlight of Depeche Mode’s vast discography and actually feels of a kind with another album that touched on alienation released that same year, Radiohead’s OK Computer.

Although, in many ways, Ultra’s nervy claustrophobia was actually an indicator of where Radiohead were ultimately headed. Once more, Depeche Mode were leading the way, even if the media were slow to recognise it.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.