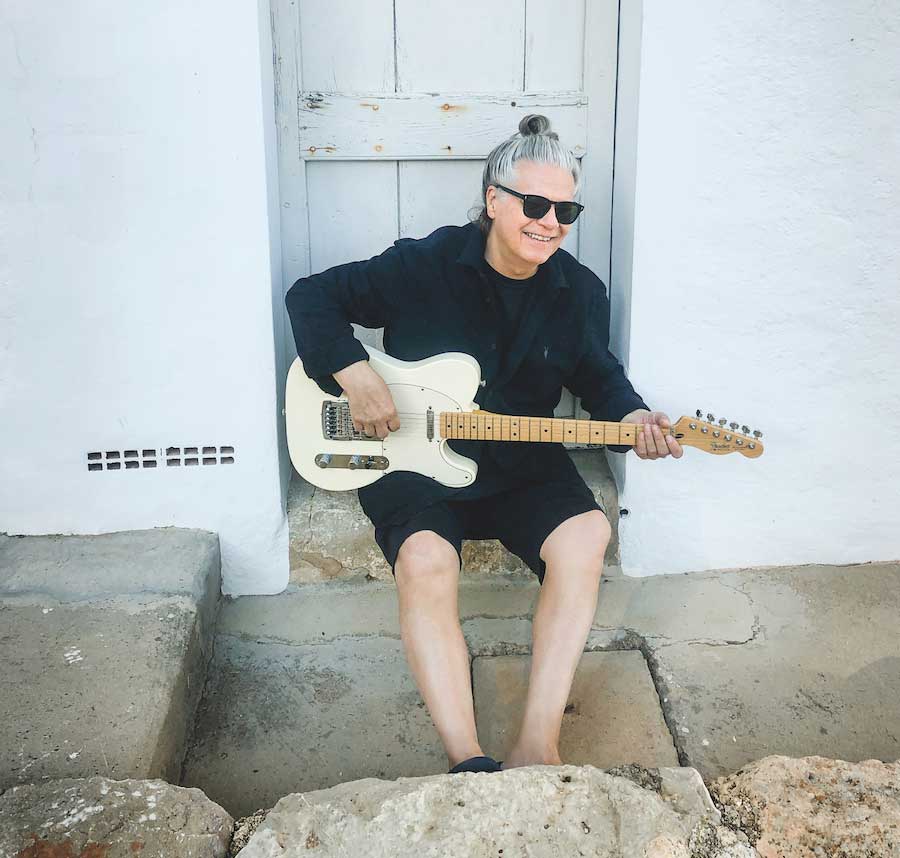

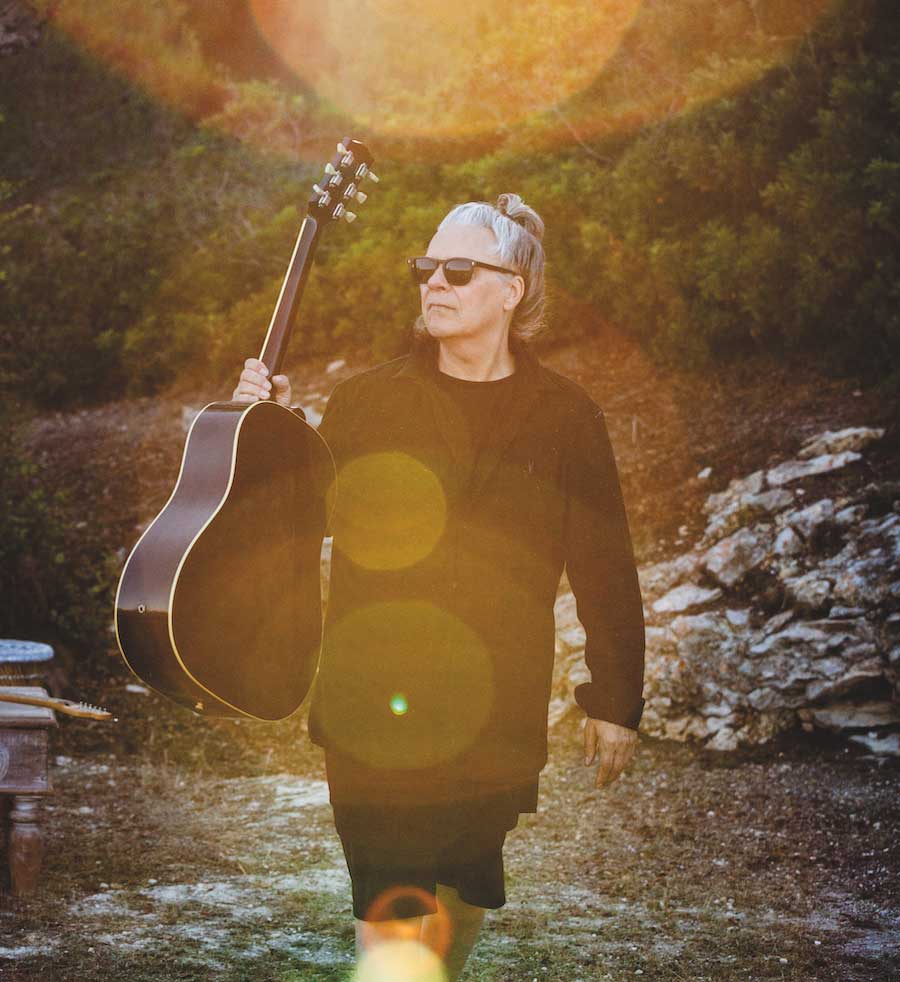

Andy Taylor

Refusing to be dragged under by his terminal cancer diagnosis, Andy Taylor has not only been playing guitar on a new Duran Duran album but also making his first solo record for 33 years. Explaining the importance of music in staying strong during his illness, he tells Classic Pop how easy it’s been with his old bandmates, why he left twice over… and his hopes of getting back onstage.

“Frankie Goes To Hollywood? They were good boys, it’s lovely to see them back. I had a messy show with them in Paris once. I got up to play with them in the encore. When I put my guitar on, they’d put an elastic strap on it. There were 10,000 people in the arena, while I was trying to play Relax with an elasticated guitar bouncing up and down on my body. Frankie were pissing themselves.”

This is how Andy Taylor introduces himself to Classic Pop, over Zoom from his home in Ibiza the afternoon after Frankie’s comeback performance at Eurovision.

Given how his terminal cancer was so publicly revealed during Duran Duran’s induction at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame last year, you might expect Taylor to appear vulnerable and a little weary. Instead, Duran Duran’s old guitarist is a vital force, rattling off terrific pop tales at a rate of knots. Before our interview, his manager tells us: “You’ll like Andy. Proper rock and roll, ever so garrulous.” He wasn’t wrong.

Andy is here, at least nominally, to discuss Man’s A Wolf To A Man. Only his third solo album – and his previous collection, 1990’s Dangerous, was a covers record – it’s as unpredictable, sparky and joyful as the man himself, switching from the glam of This Will Be Ours to the robofunk of Reachin’ Out To You via wistful ballad Big Trigger, all with a restless energy.

The album’s genesis is inevitably eccentric, as Taylor explains: “I had a FaceTime call come up: ‘Hartwig Masuch, BMG CEO.’ I thought: ‘The CEO of BMG? I’d better take this.’ Hartwig told me he was a long-time fan. He was a very personable guy, one of the few CEOs of a record label who doesn’t have lizard-like tendencies.”

The exec said he’d love Andy to make whatever album he wanted for his label, perhaps a new Power Station record? “I told him that wasn’t very easy,” laughs Taylor. “Most of The Power Station are dead. Even John Taylor has come close a couple of times.”

With a potential record deal unexpectedly arriving, the guitarist followed the ethos of his former Power Station bandmate, Robert Palmer. “Robert’s rule was: ‘You can go anywhere you want,’” reveals Taylor. “When you’re expressing a song, so long as you have the feeling of ‘I love this and I’ve nailed it,’ you can work out afterwards which songs work together. Robert was an absolute master of going everywhere – you can’t get two more different cultures than Addicted To Love and Pressure Drop.

“After Hartwig’s call, suddenly I’d been given the freedom to do what the fuck I want again. Great! There’s a big collective consumption of different music throughout my life, but I always get back to Bowie and The Beatles.”

Although he’s been a producer for Rod Stewart and Gun, Andy is drawn to bands: not just Duran Duran, but consistently playing with Reef, too. Man’s A Wolf To A Man was written and produced with The Almighty singer Ricky Warwick and Swedish electronica artist Mattias Lindblom.

Andy Taylor

“The album was all made in one room, with one or other of Ricky and Mattias,” notes Taylor. “I don’t think you need more than two people to write a song, despite the current pop world’s way of eight writers on everything. My process is very band-oriented. I prefer having that other person for checks and balances on songs. Otherwise, I start having weird conversations with myself: ‘What do you think, Andy?’ ‘Well, Andy, now that you ask…’

Initially completed before the pandemic, Taylor used lockdown to reassess the album. The big change was ensuring that he sang it all. Reef’s Gary Stringer had sung on most of the album initially. Andy’s wife Tracey was key in the change, as he reveals: “My wife was particularly the one saying: ‘Why aren’t you singing more on the album?’ She doesn’t normally get involved in that side of my work, so that made me think: ‘Hmm…’

Tracey’s concerns over her husband getting to express himself were partly because, as Andy states simply: “I was thinking this was going to be my last album. My cancer diagnosis was only heading one way.”

While Taylor’s stage four prostate cancer diagnosis was made public last November, he’s been living with the illness since 2018. He’s bleakly funny describing how keeping his condition private nearly scuppered his reunion with Duran, revealing: “By the time we found out Duran were getting inducted into the Hall Of Fame, we’d been discussing a couple of other projects.

“The weekend our induction was announced, it turned out Duran were going to be in Ibiza. So of course, they were going: ‘Hey, let’s get together!’ But I was in London, having cancer treatment and was unable to say anything to anyone. The one time Duran were in Ibiza is the one time I wasn’t. They must have thought: ‘Really, Andy?’”

There are many reasons Andy’s distance from Duran Duran since he left in 2006 during the Red Carpet Massacre sessions has been so vague. Chiefly, it’s because neither Andy nor the band see it as anyone else’s business. As Taylor puts it: “My rule is, if it’s not been said in the press, I won’t talk about it.”

But now that there’s an ease between all the band again, Taylor is happy to confirm it really was a simple musical difference that led to his departure. Andy states: “I couldn’t do the Timbaland album, because it just didn’t move me. I was saying to the others: ‘Why do we need this?’ There’s so much talent in that band, I never felt the need to bring other people in to write with Duran. It bugged me.

“It wasn’t about getting my own way. But if the force is against you, it’s difficult. When you’re older, band rules can become very difficult. The band rule was: ‘The band comes first’ and I thought, ‘No.’

“The general feeling was ‘You should come with us over here’ and I just couldn’t. I don’t know what it is with me that means I just can’t do that. It felt like someone shutting an elevator door on me that I couldn’t get past. There has to be a balance, and I couldn’t feel it. I had the same feeling as I had when I left during Notorious: ‘I’m going to miss all this… again.’”

- Read more: 40 of the best Duran Duran songs – year by year

- Read more: Duran Duran: Future Past interview

Andy is mature and easy-going enough to recognise that what felt incredibly important 17 years ago shouldn’t get in the way of the relationships he’d forged decades before. “We’ve been through some crazy shit together,” he laughs. “I’ve thought a lot about what happened when we were youngsters. All of it comes back, including why I left.

“You re-evaluate it and realise that perpetuating arguments over petty things is pointless, because the only person you’re really falling out with is yourself.

“A band is an entity, it’s not about one person. Duran Duran is a living entity. When you think about its journey, the bad bits are amplified too often. When the dust settled, there was no animosity there. It was creative, not personal. We’re Pink Floyd in reverse.”

Reef with Andy Taylor (second from left)

That creative relationship has been restored on Duran Duran’s new album. Inspired by last year’s Halloween-themed gig in Las Vegas, it sees the band cover several suitably spooky songs including Paint It Black, Ghost Town and Cerrone’s Supernature, as well as goth-tinged reworkings of Duran tunes such as Secret Oktober, New Moon On Monday and Shadows On Your Side.

“Simon is in great voice on the album,” enthuses Taylor. “There’s a particularly great cover of Siouxsie And The Banshees’ Spellbound and our reworked Night Boat is fucking fantastic. It’s a fun record.

“I just loved playing with them again. We probably didn’t understand it when we were young, but we know what we’re about now. John’s bass playing is tight as fuck: him and Roger are one proper rhythm section. Having the original rhythm section is a big thing for a band. Not to criticise anyone else, but when me, John and Roger play together, there’s nothing quite on a par with it. I’ve found that again on the new record. It was: ‘Yes, that’s my place!’ so quickly.”

Seeing Andy talk so enthusiastically about Duran Duran, his blond manbun bouncing with glee, is wonderful. An enigma who’s generally kept his counsel about being part of the world’s biggest band in the 80s, Taylor explains of his attitude: “I avoid playing up to my red carpet alter-ego. I created that alter-ego and at one point it merged into my daily life. I created a monster, along with four other monsters. Duran was a hydra-headed monster, and I like to think I’m in recovery from the music business.”

“They had the chorus of Girls On Film and that was about it. But once we started jamming stuff, an attitude came out. I’d been around every musician in Newcastle, but something different was going on in Duran. Our only gear was a shitty amp and a distortion box I could get some juice out of. But that juice, plus Nick and John’s make-up and weird shoes, it was enough.

“I was never destined to work in the shipyards, as I wanted to be Mick Ronson. I wanted to be the guy wearing make-up, and the vibe of The Rum Runner helped Birmingham feel like another planet. Another band, Fashion, would hang out at The Rum Runner with us. They were really cool, too, and I thought: ‘We don’t have this in Newcastle!’

“The silver nail in my coffin for becoming a glamorous pop star was Duran’s manager, Paul Berrow. He had a BMW, and in April 1980 owning a BMW was like owning a space shuttle. I realised: ‘This is where I need to be!’

- Read more: Making Duran Duran: Duran Duran

“If all that wasn’t enough, there was the name. I was a fan of Barbarella, so when I answered the audition ad and was told ‘We’re called Duran Duran’, I thought ‘Yeah, clever.’ Duran Duran is a name like Coca-Cola, it just rolls off the tongue.

“Led Zeppelin is a big name, Duran Duran is an arty and sexy name. Nick and John: one is Duran and the other is Duran, too. They were Duran and Duran. The band was their baby.”

Despite being the newcomer, Andy was easily able to find his place in Duran. “I had a 100-watt Marshall amp,” he chuckles. “A loud amplifier and I was in there. The Berrow brothers said that, without a guitarist, America would be out of reach. EMI said it, too, that they had more faith in Duran than a lot of other synth acts because we had a guitarist.

“In America, our contemporaries were Prince, Michael Jackson and Van Halen. Two of the best guitarists in the world, while Jackson sang with some of the greats. The guitar was still huge in America.”

The Power Station allowed Andy and John to hone their rock side, a band even more successful in the States than back home in the UK, featuring Chic’s Bernard Edwards and Tony Thompson as well as Robert Palmer.

“I love The Power Station album,” says Taylor. “But when I listen to it, there’s a little sadness. Tony, Bernard and Robert were all young when they died. I used to call it ‘The Curse Of The Power Station’ – and then it happened to me.

“But that album also brings home what a great time it was. Duran Duran never planned any of it but when we got together it was like everyone had been waiting their whole life for that moment. As soon as we hit the go button, we were successful everywhere around the world. To this day, we’ve got the most successful Bond song. That’s mental.

“When Some Like It Hot came out, that was No.2 while A View To A Kill was No.1. One thing I was sensible about in my mid-twenties was to realise: ‘Kid, you ain’t ever going to surpass this.’”

As stellar as life was, the accepted wisdom around Duran Duran is that their side projects helped splinter the band. Was The Power Station’s tour of the US as debauched as everyone claims?

“I couldn’t possibly comment,” insists Andy, briefly clamming up. He reasons: “Duran have always been a class act. They don’t try to sell themselves on the debauchery. I love The Rolling Stones but, whenever you think about them now, what comes to mind first is the lifestyle. Duran have always aspired to have a touch of class. Despite my shit shoes, they’ve maintained that.

“What I will say about that Power Station tour is that, after the commercial success with the album, Robert dropped out. It was only meant to be a one-off album anyway so, without Robert, what was the point? There was no point to that tour, apart from ‘Let’s have a laugh.’ I will say there’s only bits of it that I can remember.”

It was during The Power Station that Taylor began to have doubts about life in Duran. He remembers a drunken interview with Robert in Japan – “They had these sake machines on the street, and the interview was at 10am” – which was so chaotic that an EMI rep tore into the pair, accusing them of disrespecting their TV interviewer. Andy remembers: “The EMI guy was saying: ‘Don’t you care about your career?’ I told him: ‘What career? How do I get promoted?

“That was what I began to find frustrating. I was in my mid-twenties and was thinking: ‘Where do I go from here?’

“But that’s the point where the music industry should have stepped in to help.

“I’ll take every bullet I deserve for leaving the band. But why is it always the members of a band who are at fault when it stops?

“In music, it’s only ever the surface that gets reported. Duran were falling apart. Roger wasn’t well. I was having doubts. All of the industry people who had dined out on Duran Duran from the very start? When it was time for them to be honourable, to stand up and help us, they weren’t there.”

If the reportage around Duran can be frustrating, Andy’s illness has reaffirmed his belief in the power of music itself. He’s never taken the creative side for granted and says now: “Music gives me a destination to aim for. This illness takes so many other things away, so the motivation of having music giving me something of worth in my life,

it’s invaluable.”

Andy is having pioneering cancer treatment that he hopes will prolong his life by several years. As he explains: “I’m truly blessed to get this new treatment.

“There’s a lot to it yet, but getting back on stage one day is a big marker for me.

“I’ve got more music to make – and I’m going nowhere until I get it done.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.