Robert Palmer

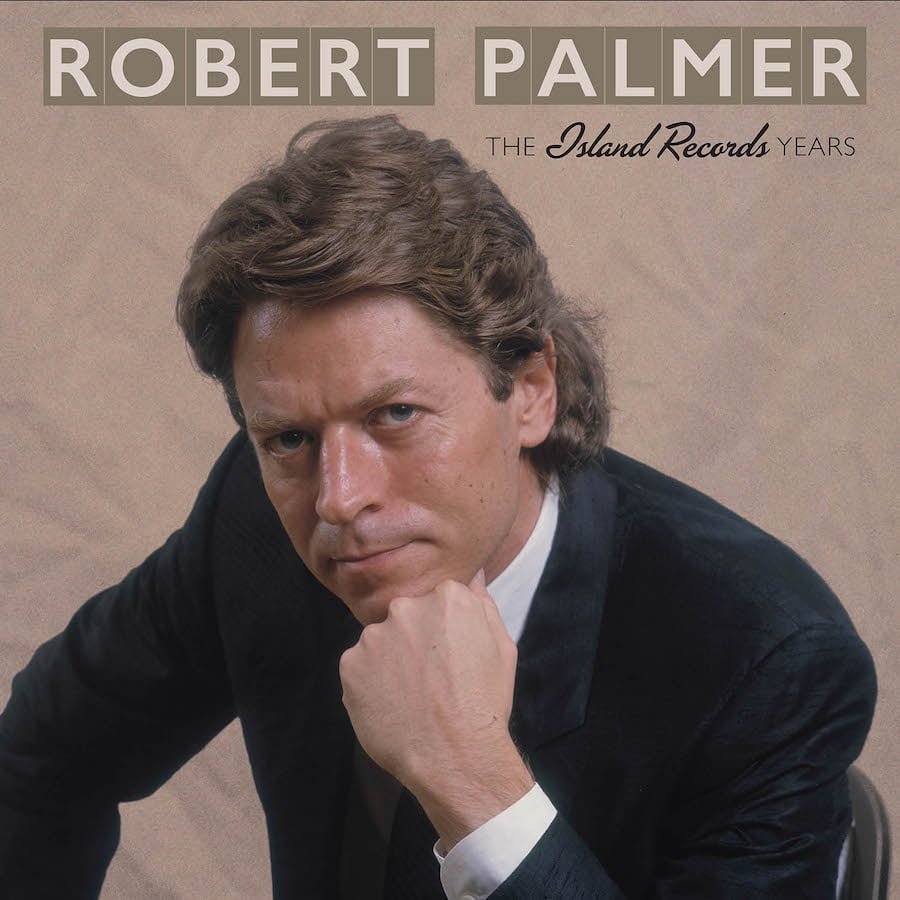

Far from the dilettante playboy his image suggested, could the shapeshifting Robert Palmer be one of the most underrated singer-songwriters of his era? We reassess his chameleon-like solo career and collaborations with supergroup The Power Station…

“I hardly ever get asked about music,” Robert Palmer told The Guardian in 2002. “I do, however, get asked about the Addicted To Love video and my suits on a daily basis.”

When he died just a year later, of a heart attack at the age of just 54, sadly that’s what most of the obituaries focused on – the rock-pop playboy who seemingly prized style over substance, hedonism over musical integrity.

But while other sharp-suited lotharios such as Bryan Ferry are celebrated as rakish geniuses, somehow Palmer’s considerable contribution to music seems to have been cold-shouldered.

The image of Robert Palmer that’s seared into our collective memory is of him performing amidst a bevy of identical-clad supermodels, a perfectly coiffed sophisticate luxuriating in the pages of a Vogue photoshoot.

Addicted To Love

The Addicted To Love video was one of the defining promos of the 80s, and proved so insanely popular that Palmer reheated the idea for follow-up singles I Didn’t Mean To Turn You On and Simply Irresistible.

Those visuals, however, have overshadowed pretty much everything else Palmer ever did, and caricatured him as someone for whom music was somehow secondary to looking good.

That he was once honoured as Rolling Stone’s Best Dressed Male Rock Artist and told interviewers “I guess I always treated music as a hobby” only added to the sense that he was not somebody to be taken seriously.

Yet a closer look at his music suggests a more compelling and intriguing figure than the obits painted. This was an artist who, over a career spanning 30 years, proved as restless and daredevil a spirit as David Bowie taking in such genres as funk, synth-pop, soul, reggae, jazz, arena rock, bossa nova and blues.

You see, there was always more to Robert Palmer than met the eye. Even his beginnings belied his image as a designer-suited Romeo.

Not many pop stars – especially ones that hang out with supermodels – have Batley in West Yorkshire on their birth certificate. Yet this is where Robert Allen Palmer came into the world on 19 January 1949.

That said, his family upped sticks to Malta when he was just a few months old, returning to Yorkshire 11 years later, this time to Scarborough where his mother ran a guest house and where his father was now stationed in the Royal Navy.

Cultivating A Career In Music

Robert’s years abroad meant that, by the time he was at his new school, he was “the only one who spoke Oxford English.” At school, as in music decades later, Robert Palmer never quite fitted in.

By this point, he was already obsessed with music. While in Malta, he’d lapped up the sounds of Otis Redding, Billie Holliday, Wilson Pickett and Nat King Cole on the American Armed Forces Radio Network.

By 15, he’d enrolled at Scarborough School Of Art & Design and set up his first band, The Mandrakes. After a cleaner accidentally binned much of his coursework, Palmer dropped out and decided his energies would be better spent cultivating a career in music.

And it worked – even though all of the bandmembers were teenagers, The Mandrakes secured some high-profile gigs at the time, supporting The Who and Jimi Hendrix as well as touring Scandinavia.

Palmer was still a teen when he joined his next band. The R&B-powered Alan Bown Set were already a favourite on the live circuit when they approached Robert to replace their hastily-departed frontman Jess Roden for a show at the Scarborough Spa.

Palmer would record one album with the band, titled The Alan Bown!, before moving to London where he hooked up with a jazz-rock fusion band named Dada.

Pressure Drop

Among its 12 members was a singer named Elkie Brooks (yes, that one) and her husband Pete Gage and, before too long, the three split from Dada to form their own blues rock outfit, Vinegar Joe.

Though they recorded three albums for Island Records, commercial success somehow eluded Vinegar Joe and they split up in 1974.

But Island, and specifically its founder Chris Blackwell, had high hopes for the band’s co-vocalist and signed Palmer on a solo deal, packing him off to New Orleans to work with a cherry-picked group of top session musicians.

Sneakin’ Sally Through The Alley arrived in September 1974 and saw Palmer playing alongside American funk group The Meters, keyboardist Art Neville and Lowell George of Little Feat.

Though it only managed a No.107 placing on the US Billboard Chart, Island still had enough faith in their freshest signing for a second long-player. Pressure Drop from 1975 displayed more of a reggae touch – its title track was a cover version of the classic Toots & The Maytals cut – but again failed to take off commercially.

Even its self-penned lead single, the brilliant, yacht rock-anticipating Give Me An Inch, didn’t chart.

Breaking The Charts

1976’s Some People Can Do What They Like LP fared better (No.46 in the UK, No.68 in the US), but still struggled to produce a hit.

The Caribbean-accented Every Kinda People – written by former Free bassist Andy Fraser – from 1978’s Double Fun, would be the first of Palmer’s singles to break the UK and US charts, peaking at No.16 in the States and No.53 on home soil.

Where Double Fun had boomeranged from blue-eyed soul to disco and funk to lounge jazz, Palmer’s next album, the following year’s Secrets, would be more straight-ahead rock, producing a US Top 20 hit in Bad Case Of Loving You (Doctor, Doctor), a robust cover of the Moon Martin original.

1980’s Clues found Palmer branching out even further, embracing New Wave on the Talking Heads-aping Looking For Clues (that band’s drummer Chris Frantz plays on the track, a return favour after Palmer guested on their 1980 album Remain In Light) and working with Gary Numan on the beguiling Found You Now.

Lead single Johnny And Mary, despite its sombre, sequencer-driven eeriness, would be the album’s biggest hit. Certainly by now, the public were becoming aware of Robert Palmer, even if they couldn’t quite get a handle on what he was about.

The Power Station

After scoring a UK No.16 hit with a cover of The Persuaders’ Some Guys Have All The Luck (from his Maybe It’s Live album), Palmer looked to calypso and soca for 1983’s Pride. Despite Some Guys’… success, Pride’s duplet of singles – You Are In My System and You Can Have It (Take My Heart) – failed to tickle the Top 40.

On 23 July 1983, three months after the release of Pride, Palmer performed at Duran Duran’s open air charity concert at Villa Park, the home ground of Aston Villa FC, and, backstage, started chatting with John Taylor and Andy Taylor.

It was a friendship that would eventually lead to the formation of one of the 80s’ great supergroups – The Power Station.

Convened initially by John and Andy (along with Chic’s Tony Thompson and Bernard Edwards) as a backing band for John’s then-girlfriend Bebe Buell’s planned solo record, the duo had believed that there was a future for the group beyond this one-off, only with a revolving line-up of vocalists.

While Mick Jagger, Billy Idol and Richard Butler of The Psychedelic Furs were all considered for the planned album, it was only after they’d invited Palmer to record vocals for the song Communication that they decided he was their man, hiring him to sing lead on all eight tracks of 1985’s self-titled LP.

Three singles were released from the record, Some Like It Hot (UK No.14), Get It On (UK No.22) and Communication (UK No.75), with the album peaking at No.12 on home soil and No.6 in the US.

The Right Profile

The success of The Power Station project led to a planned tour, only for Palmer to quit the band, forcing them to hire Michael Des Barres (formerly of Silverhead, Chequered Past and Detective) for the series of gigs. The sometime actor would also cover for Palmer for The Power Station’s turn at July 1985’s Live Aid concert.

Whatever Palmer’s reasons for leaving, it’s undeniable that his time in The Power Station significantly increased his profile. In Number One magazine, Palmer hit back at claims that he joined the group for the bucks: “Firstly, I didn’t need the money,” he said, “and secondly the cash was a long time coming. It wasn’t exactly an experience that set me up for retirement.”

By the time of Palmer’s next record, 1985’s Riptide, he was a bona fide star and the album would become the singer’s biggest hit to date, peaking at No.5 in the UK and No.8 in the States.

Proving there were no hard feelings, Andy Taylor and Tony Thompson guested, while Bernard Edwards was on hand as producer.

No wonder that, in many ways, it sounds like another Power Station album. When it was suggested by Number One magazine that he’d appropriated the Power Station sound for his own LP, the singer snapped back: “Listen, I gave The Power Station that sound. They took it from me, not the other way around.”

Simply Irresistible

The album would birth Palmer’s signature hit. Addicted To Love – no doubt helped by that video – would peak at No.5 in the UK and No.1 in the US.

The track had actually been intended as a duet with Chaka Khan, only her record company wouldn’t grant her a release to work for Island. Khan’s vocals couldn’t be used on the track, but Palmer credited her for her part in developing it as well as her contributions to the arrangement.

A total of five singles were released from Riptide and those blazingly iconic videos secured Palmer a regular place on MTV’s playlists.

But it wasn’t to last. Riptide’s follow-up, Heavy Nova, took Palmer’s propensity for fusing genres too far, with its whisking together of – as implied by its title – heavy rock and bossa nova.

Though Simply Irresistible (US No.2) and She Makes My Day (UK No.6) were hits, the album only made No.17 in the UK and No.13 on the Billboard.

1990’s Don’t Explain performed slightly better. A cover of Marvin Gaye’s Mercy Mercy Me/I Want You and a buddy-up with UB40 on a version of Bob Dylan’s I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight both went Top 10 but suggested that inspiration was in short supply. The songs would be Palmer’s last UK singles to go Top 20.

The 90s would see Palmer drifting creatively. Ridin’ High (1992) saw the singer delve into the Great American Songbook, while 1994’s Honey tilted uncomfortably toward AOR.

A Power Station reunion in 1995 produced one final album, Living In Fear, which failed to hit the creative and commercial heights of that first record 10 years before.

Smooth Operator

He returned to his love of R&B for 1999’s Rhythm & Blues and reached back to Delta blues for his final studio album, 2003’s Drive.

There were, however, the seemingly endless compilations. For much of the 90s, Palmer was rarely off the sofas of daytime TV, promoting some new greatest hits collection.

1989’s Addictions Vol.1 made UK No.7, Vol.2 from 1992 reached UK No.12 and 1995’s Very Best Of Robert Palmer hit UK No.4.

Even if the public weren’t keen on new Robert Palmer material, it seemed, they were still fans of his late-80s purple patch.

Yet critically, Palmer was and remains shamefully misunderstood. Maybe it was the care that he devoted to the visual presentation of his music.

To many, who prize authenticity over artifice, his cultivated veneer of sophistication proved off-putting, while his continually shapeshifting musical persona meant that he appeared like a dilettante, dabbling in, but never fully committing to, a plethora of genres.

Trailblazing Artist

Yet one could argue that Robert Palmer’s vast oeuvre was one that reflected his adventurous and ever-curious attitude to music.

And that image of him as a rock and pop playboy? There are fewer scantily clad females on his record sleeves than you imagine, far less than the generally more respected Bryan Ferry. Another misinterpretation.

Island’s compilation, The Island Years 1974-1985, is a chance to look back at Palmer’s output before he became that MTV favourite and to remember what a fearless and trailblazing artist he really was.

Not everything works, but you could say the same about Bowie, or any other perma-shapeshifting musician. And judging him on that one video is akin to only remembering David Bowie for Let’s Dance.

If any 80s performer is worthy of a deeper dive, it’s Robert Palmer, that most criminally underrated of musical chameleons.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.