A new lease of life for songs lost to the bedroom, two brothers with Michael Jackson-sized ambitions, and a synth-pop pioneer at the controls – these were the ingredients necessary to forge Steve McQueen, the classic second album by Prefab Sprout

Prefab Sprout: Steve McQueen cover

With Prefab Sprout’s second album, Steve McQueen, the chronology is all back to front. To fully understand the genesis of this most exceptional of literate pop creations, we must return to the tiny hamlet of Witton Gilbert, a hefty stone’s throw from Durham, where in the late 70s and early 80s, a young Paddy McAloon first conceived much of this sophisticated masterpiece.

It seems a youth spent pumping gas alongside younger brother Martin, isolated in this remote rural enclave, gave birth to a bedroom lyricist and songwriter of an altogether different class.

It was there the two siblings soaked up a wide array of literature, from detective novels to poetry, and indulged in a library of disparate sounds – Bowie to The Beatles, Steely Dan to Captain Beefheart… Sondheim to Stravinsky.

As hungry to unravel the secrets of the mainstream greats and Broadway scores as those artists occupying more distant outposts, the McAloons’ palette was far more eclectic than most.

The contrast was unlike anything I’d heard, and with the wide harmonies he wrote for her, it all added up to something beautiful and precious.

With this self-initiated cultural education and armed with his mother’s beat-up Spanish guitar through which to make sense of it all, Paddy created a raft of songs that were distinctly – and purposely – out of step with most of what was going on around him.

“I was into being as intensely yourself as you could be,” he said of the period to Sound On Sound in 2014. Such was Paddy McAloon’s desire to become the “Fred Estaire of words” (as he wryly sang in Paris Smith some years later) that he wrote extraordinarily prolifically from the time that he could.

Here was a kid “only really happy when I’m writing songs”, as he told Record Mirror in 1985. Those countless ideas were scribbled on sheets of paper and stored – hoarded, even – in piles and boxes in his bedroom.

This valuable cargo would grow exponentially over the next few years and Paddy would emerge from his bedroom with enough odd-pop gems to play for hours on end – and with Michael Jackson-sized ambition (about whom he’s written an entire unreleased album).

Together with Martin on bass, and schoolfriend Michael Salmon on xylophone, guitar (and eventually drums), the three-piece decamped to the workshop-cum-rehearsal room over the road and were soon a local live fixture.

- Read more: Prefab Sprout albums – the complete guide

“Freeform and electric,” as Paddy once put it, Prefab Mk.I were a far cry from the band they would become, and entirely unaware that the material they were forging wouldn’t come to fruition until almost a decade later.

By the time local indie Kitchenware Records put out the band’s debut album Swoon, new drummer Graham Lant and fan-turned-backing-singer Wendy Smith had joined the group and the old songs had been shelved in favour of newer fare.

That is, until another major player in the Prefab narrative entered the frame. And he came from a different world entirely.

When Swoon’s first single Don’t Sing was given the Jukebox Jury treatment on Radio 1’s Roundtable, DJs Tony Blackburn and Mari Wilson used the song’s title as a lazily adopted barb with which to dismiss the track, but guest reviewer – synth-pop soloist Thomas Dolby – thought otherwise.

Having sat through Toy Dolls’ Nellie The Elephant and Alvin Stardust’s So Near To Christmas, Don’t Sing was clearly a revelation. “Out of the speakers came something miraculous!” he recalled in his memoir. “The song had weird time signatures and key changes and no discernible hook… In short, it was utterly fantastic.”

In that moment, a glorious chain of events was set in serendipitous motion. Dolby would not only end up producing Prefab Sprout’s second album – his first major production duty – but would be entrusted to handpick the songs from McAloon’s dog-eared bedroom vault.

I thought it was a brilliant partnership. My songs and his way of producing. It was the perfect balance.

Back in the North East, Paddy and Martin were tuned in. “I’d heard him sticking up for us on the radio,” Paddy told Melody Maker. “I thought, ‘Now that would be an unusual combination”. I’m not one for repeating formulas. I want to work with people who can teach me something.”

It was the band’s new label boss at CBS, Muff Winwood, who was first to float the idea. “Paddy and I didn’t get it at all, initially,” admitted Kitchenware’s Keith Armstrong. “We thought Muff had gone mad.”

Nonetheless, a meeting was arranged to probe the possibilities. Amidst the unpredictable nature of Paddy’s songwriting – all tempo changes, odd time signatures, off-kilter hooks and ambitious arrangements – perhaps a tech-savvy, pop-minded mentor – a steadying hand – wasn’t such a bad idea.

“I’d read in a magazine somewhere that he was working with Michael Jackson, and I thought, ‘That’s good enough for me,’ Paddy said. With no demo available, Dolby paid a visit to Witton Gilbert to hear Paddy play.

“I took the train up,” Dolby remembered to Puremusic. “Paddy took me to his room and pulled out this stack of songs. He’d squint at them and strum his way through them. He would write notes for chords and melodies over the top of the lyrics, but primarily, it was about the poems.”

Seated on Paddy’s bed, Dolby listened enthusiastically to complex “asymmetrical phrases” with “odd numbers of beats” and “tricky chord changes”. “The songs came thick and fast,” Dolby enthused, “with soaring melodies, finely nuanced chord sequences, and poetry that alternatively cut like a knife and tugged at my heartstrings.”

The producer returned to the station clutching a cassette recorded on his Walkman and, by the time his train pulled into London, he’d narrowed the 40-something songs down to a shortlist of 12; some of which originated as far back as 1976.

Steve McQueen was to be a record, the majority of which would tell the stories of a boy barely out of his teens, retrospectively sung by the man he had grown into. Dolby’s job was to translate Paddy’s skewed genius for the outside world – or, as he put it: to be a “caretaker for someone else’s music”.

- Read more: Paddy McAloon interview

Swoon had been a challenging listen; Steve McQueen was to be just as pioneering, but palatable to boot. And not only that – with CBS onside – this new album was to be made under more luxurious circumstances. Swoon took 18 days: Steve McQueen needed three months.

In Autumn 1984, the band were installed at London’s Nomis Studios to begin sessions under the working title ‘June Parade’.

“My first job as producer would be to encourage the band to simplify the arrangements, create space for all the parts, and restructure the songs, without losing the focus of the vocal and lyrics,” wrote Dolby.

“[Paddy’s] voice was extremely intimate and sensual, while Wendy’s was sterile and detached; the contrast was unlike anything I’d heard, and with the wide harmonies he wrote for her, it all added up to something beautiful and precious.”

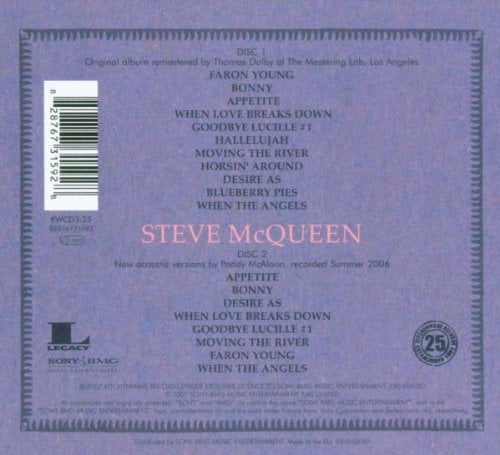

Out from under the bed came diverse tracks such as Faron Young, Bonny, Goodbye Lucille #1 and Hallelujah. Dolby added Fairlight, piano and synth and worked on intros and solos “to propel it along while making space for Paddy and Wendy’s vocals to slip into”.

New drummer Neil Conti streamlined the sound, as did Dolby collaborator Kevin Armstrong, who added “some grittier chunks on his Les Paul”.

With arrangements in the bag, the ensemble moved to Marcus Studios in Queensway, where engineer Tim Hunt set up baffles and mics in the large wood-panelled live room. “The result,” wrote Dolby, “was an open, natural sound with the punchy and organic rhythm section and piano driving the grooves.”

Overdubs were added, including doubling Wendy’s vocals with synth to add some gloss.

The first the world heard of the record was pacemaker single When Love Breaks Down, albeit a version produced by The Cure’s then-bassist Phil Thornalley quickly lost amidst cornier festive fare. Dolby made sure to recut the vocals and remixed the song to fit the Steve McQueen mould.

The album appeared in June 1985 like the sorest of thumbs amidst a habitat dominated by synth-pop and MOR, and clawed its way to No.21.

After several failed attempts, When Love Breaks Down managed No.25, but the singles that followed underperformed: Faron Young made No.74, Appetite stalled at No.92, and Johnny Johnny (Goodbye Lucille #1) teetered at No. 64.

While sales took time to build – it eventually won Platinum status – the critics lapped it up. Hip vindication arrived when NME placed it at No.4 in its Albums Of 1985 poll, alongside a cast of cool including The Jesus And Mary Chain, New Order and The Fall.

- Read more: My Pop Life – Tim Farron MP

Renamed Two Wheels Good in the US (for legal reasons), it only managed No.180, yet Rolling Stone declared that it was “complex but irresistible”.

Where Swoon was charged by some as being too self-aware – or “a tour de force of self-indulgence”, as Melody Maker impugned – with Thomas Dolby as its rudder, Steve McQueen sat just right.

In many ways, Steve McQueen was born of two people’s visions. Paddy has even gone as far as to call it “Thomas’ album”. “I thought it was a brilliant partnership,” he explained. “My songs and his way of producing. It was the perfect balance.”

Alongside Steve McQueen’s innocent themes of love, Paddy’s namedrops and odd references evoke a world that’s far too tempting not to dip a toe into.

As a result, Prefab’s second album has gained exalted status among lovers of intelligently written, sophisticated – and emotive – pop music and regularly makes the ‘Greatest Albums Ever’ listings. And deservedly so.

As far removed from their peers musically as they were geographically, with Steve McQueen, Prefab Sprout put Witton Gilbert on the map.

Prefab Sprout: Steve McQueen – the songs

Prefab Sprout: Steve McQueen – the songs

1 FARON YOUNG

“Antiques!” proclaims Paddy McAloon over the faux country intro of lead track Faron Young – complete with Thomas Dolby’s equally fabricated banjo lick, forged by Fairlight. It’s an opening lyric that leads to yet more cryptic conundrums, in a track – originally a feisty rocker – that predates debut album Swoon and name-checks the now somewhat obscure country old-timer from the 50s. A true pacemaker, it contains one of the finest choruses of the lot, with McAloon wittily playing on Young’s final No.1 hit It’s Four In The Morning amidst hanging chords and floaty synths. “It’s a song wondering why people like Country & Western music when they live in the industrial north,” McAloon told NME in 1992. An earworm, but one we’re more than happy to accommodate.

2 BONNY

Conceived in May 1977 and brought back to life eight years later, Bonny first appeared in demo form on a Kitchenware Records compilation cassette from 1983 entitled Souled Out!!. While – much like Faron Young – this early sketch was tempered a little in its re-recording, the roughshod demo proves little was lost in translation. Bonny’s light acoustic riff, side-sticked rhythm and Fairlight atmospherics focus all ears on the track’s enigmatic lyrics – Melody Maker purported that it imagined “the death of his sick father”, while it’s equally identifiable as a breakup song. Lyrics aside, this is one of the more straightforward songs on the album.

3 APPETITE

Thomas Dolby’s inviting synth intro, yet more lyrical wit and with a pop melody to die for, Appetite is a standout. Here, Dolby added rolling arpeggiating synth to drive the chorus, and soft pads to mirror Wendy’s backing vocals to soothing effect, while Neil Conti supplied a classy rhythm track. “It was a song about a girl who got pregnant and the idea of her calling the kid after her lust for life,” Paddy McAloon told Stuart Maconie. “Thomas Dolby never thought he did justice to that song.” We’d disagree – it’s a perfect example of the Dolby-McAloon marriage.

4 WHEN LOVE BREAKS DOWN

For many, the album’s entry point and likely the best-known track from the set, this Phil Thornalley-produced single was released in the run-up to Christmas 1984 and faltered in the festive surge. Dolby recut the vocal and remixed the song – a slightly less bells-and-whistles version – for continuity. “It is a very personal song,” McAloon told Melody Maker. “It’s not that far removed from personal experience. I’ve worked so hard, it’s been to the detriment of other things. Relationships have suffered, I don’t mind saying that. But I know if I don’t work hard I won’t get that golden moment.” It was third time lucky when it made UK No.25 (and No.42 on Billboard’s Top Rock Tracks chart).

5 GOODBYE LUCILLE #1

Written in 1979 and originally intended for an album of tracks all with the same name (bar the number), this is known to many as Johnny Johnny, thanks to its hooky chorus refrain being used as the new title when it was released as the album’s final single. With lyrics designed for wayward teens (“Life’s not complete, ’til your heart’s missed a beat”) and a typically magnificent, yet slightly wonky hook, this was robbed of glory when it only clawed its way to No.64 in the UK charts. Nonetheless, another sparkling example of McAloon’s ever-creative handling of pop.

6 HALLELUJAH

It’s all about the guitar here, from the propulsive chorded riff, to Kevin Armstrong’s measured Les Paul solo. Add Wendy’s siren-like intro melody and crystal backing, plus typically odd key changes that take a lead from Paddy’s lyrics, and it makes for a mesmeric mix. Those lyrics are more astute than ever, overflowing with observational poetry (“sweet talk like candy rots teeth”) and typically high-brow references (“I hear the songs of Georgey Gershwin”). There’s a jazz influence, too, but from Paddy’s perspective, it’s more to do with naïve experimentation – playing by ear – than intention. Penned in 1983, this also appeared on the Souled Out!! compilation.

7 MOVING THE RIVER

Containing the immortal line: “I’m turkey hungry, I’m chicken free!”, the lyrics are among the album’s most dense. Its ubiquitous rolling brass hook and uplifting glossy exterior hide a lyrical heart that – while we would never feign to fully decipher – imply self-doubt and personal pressures. As Paddy sings: “It’s the wonders I perform/ Pulling rabbits out of hats/ When sometimes I’d prefer/ Simply to wear them,” the inhibiting weight of emotion is palpable. The perplexing reference to “money for jam”, comes from an elderly visitor to the family filling station who used to regularly advocate the pleasure of being a bookie: “Money for jam, John, it’s money for jam.”

8 HORSIN’ AROUND

McAloon almost gifted this song to a Glasgow-based band called Sunset Gun, then due to join Prefab Sprout on the Kitchenware roster, but luckily for us, the exchange never happened. “Horsin’ Around was recorded after [a] rather inebriated sojourn to the boozer and you can hear Martin laughing while I’m counting it off,” explained drummer Neil Conti. “That track is all over the place, but it was just what the song needed.” That faux-jazz feeling of fun once again juxtaposes the weighty subject matter of infidelity: “Quick to forgive and so slow to blame/ The very thought fills me with shame/ But that didn’t stop it happening.”

9 DESIRE AS

Heartbreak and synthesisers. Penned around the same time as When Love Breaks Down, this deep, tormenting exploration of lost love cannot fail to move the listener as Paddy repeats his chant-like refrain – “I’ve got six things on my mind, you’re no longer one of them” – that artfully frames the arrangement. Add Wendy’s delicate tones doubling up the big lines and some oaky sax, and the results are utterly spellbinding.

10 BLUEBERRY PIES

At just over two minutes long – and a little kookier than most – this haunting creation reveals Prefab’s Broadway infusions in a stop-start arrangement that strays playfully from the norm. Possibly the album’s most indecipherable lyrics speak of school cheats-turned-priests, “answer-me eyes” and odd behaviour.

11 WHEN THE ANGELS

The tempo – and mood – shifts up a notch, as Steve McQueen’s curtain falls with an exultant tribute to Marvin Gaye, who died shortly before the album’s release. “I wanted to talk about somebody dying young with a wonderful gift,” Paddy told Melody Maker. “The main thing on my mind then was Marvin Gaye. I couldn’t be sombre and serious like the Nightshift thing [The Commodore’s tribute song]. I wanted to be irreverent and put two fingers up at the sky.” Here, the angels are recast as “hard-faced little bastards” who “take the angel voice away”. On top of some of the album’s niftiest bass playing, this track encapsulates the record as a whole, with a bit of everything in there. The perfect closing track.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.

Prefab Sprout: Steve McQueen – the songs

Prefab Sprout: Steve McQueen – the songs