Making Japan: Tin Drum

By Steve O'Brien | July 8, 2021

Japan: Tin Drum was an album that announced big changes from the group with a more mature, haunting new groove beating at its heart. Classic Pop discovers how David Sylvian and co merged orientalism with high art to forge their final and most esoteric collection…

Few musical journeys are as far-reaching and profound as the one taken by Japan between their first album in 1978 and their last in 1981.

Much is made of The Beatles’ evolution from the simplicity of Love Me Do to the avant-garde stylings of Revolution #9 in just six years, yet Japan travelled from the try-hard glam-pop of Adolescent Sex to the stark, desolate beauty of Ghosts in just three. At the time they recorded their final album singer David Sylvian was just 23 years old.

Japan released only five albums in their brief life, but only three that really matter. “I avoid looking back at the first two Japan albums,” Sylvian said later. “They were enormous mistakes that grew out of extraordinary circumstances. We were all young and surrounded by older people who thought they knew best.”

The first album that really announced to the world what Japan could and would be was 1979’s Quiet Life. It would be their Rubber Soul, a bold restatement of the band’s musical identity, courtesy of disco godhead Giorgio Moroder.

That creative journey continued on 1980’s Gentlemen Take Polaroids and reached its zenith on what would become the group’s final, and most acclaimed record, the haunting Tin Drum.

What’s especially perplexing is that this beguiling, elliptical record would be their best-selling album, and that its third single, the defiantly uncommercial Ghosts, would become their biggest hit. When Paul Morley described Tin Drum in the NME as “gorgeously erotic” and “perfectly evanescent” it didn’t sound as though he was talking about an LP that would make it to No.12 in the album chart.

Sometimes, it seems, the public is more discerning than they are given credit for.

Named after German writer Günter Grass’ 1959 novel The Tin Drum (Sylvian was never shy of showboating his highbrow tastes), Japan’s fifth album started recording on 22 June 1981, with producer Steve Nye at the helm. Just a month before, guitarist Rob Dean had left the band after six years, and his absence hangs over much of Tin Drum.

With his departure went the last vestiges of rock in Japan, and consequently much of the minimalist arrangements on the record come courtesy of Sylvian and keyboardist Richard Barbieri.

Whereas with previous long-players, Roxy Music and Bowie were the most obvious influences, the sounds that fed into Tin Drum were more esoteric.

Sylvian had been hanging out with Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Ryuichi Sakamoto and there’s definitely a Sakamoto vibe in the album’s silky Far Eastern textures, while Barbieri admitted in 1994 that the music of avant-garde controversialist Karlheinz Stockhausen had also bled into its recording.

“Especially the abstract electronic things he was doing in the late 50s,” Barbieri explained. “Listen to a track like Ghosts, for example, and you’ll hear all these metal-like sounds that hardly have a pitch, yet subconsciously suggest a melody.”

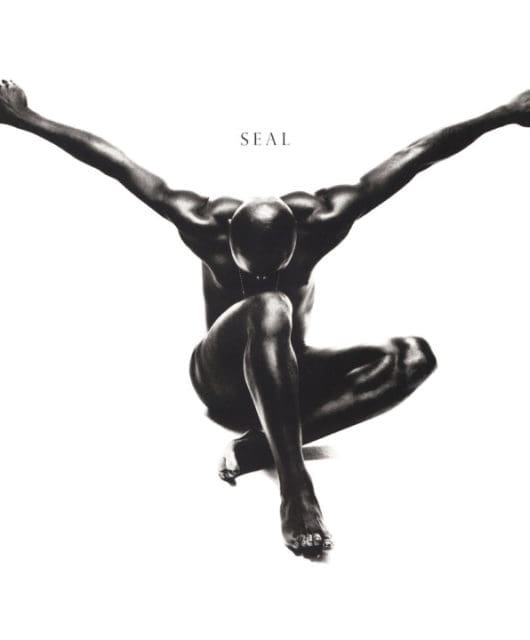

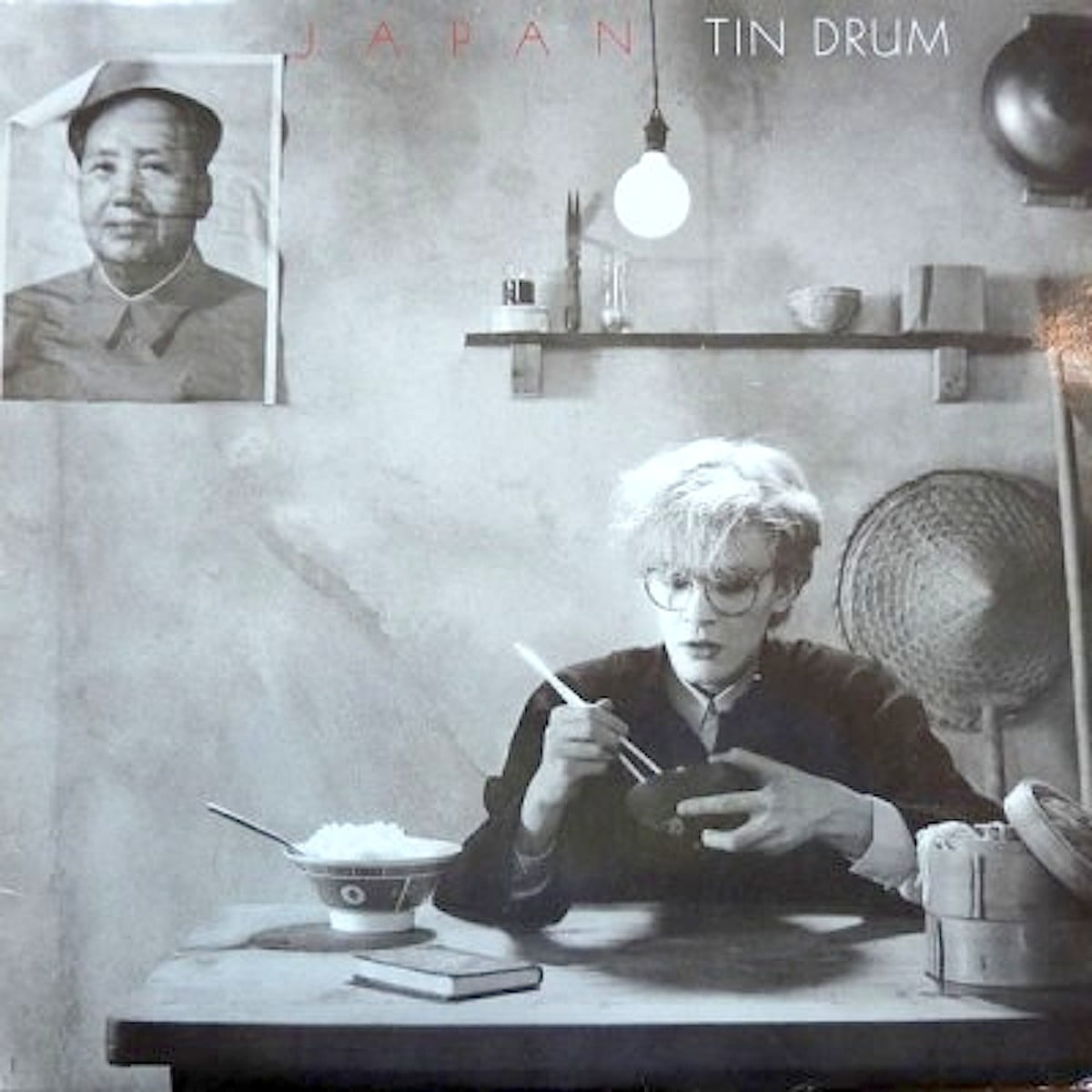

More than any other album, Tin Drum was Japan living up to their Eastern-sourced name, with the cover depicting the band’s breathlessly beautiful frontman eating rice from a bowl with chopsticks, in front of a peeling poster of Chairman Mao.

Then there are the songs Visions Of China (“We’re young and strong in this party/ We’re building our visions of China”) and Cantonese Boy (“Bang your tin drum/ Cantonese boy/ Red army calls you home”) in which Sylvian further explores his fascination with all things Oriental.

The resulting sound on the album, dubbed ‘art school Orientalism’, was strikingly different to anything else around it at the time, in the charts or beyond.

Much has been made over the years of Japan being proto-New Romantics, but the truth is, there was never much of a crossover between Japan and the burgeoning New Romantic movement beyond a penchant for blusher.

“For them, fancy dress is a costume,” the singer said dismissively of the Blitz posse. “But ours is a way of life. We look and dress this way every day.”

The public may have thought they were being granted a taste of Japan’s next album with the April 1981 single release of The Art Of Parties, but the version that would turn up on Tin Drum was a rather different beast, shorn of its funky, new wave rhythms and given a more subtle, sensuous makeover.

It would prove typical of the LP, which seemed intent more on evoking a mood and a vibe than delivering chart-targeted melodies.

Japan: Tin Drum – The Recording

Crucially, Nye was unfamiliar with Japan’s work and decided, before he started the job, not to listen to any of their previous output. “As it turned out, I don’t think there would have been much to gain in this particular instance,” he told author Anthony Reynolds for the book Japan: A Foreign Place, “since Tin Drum was such a unique album and not really comparable, which I’m sure was the way Japan wanted it anyway.”

Even the recording of Tin Drum was markedly different to how Japan had worked before. The group found themselves living and recording at The Manor Studios, a stately manor house owned by Richard Branson, and located in the picturesque village of Shipton-on-Cherwell in Oxfordshire.

“The Manor was residential, so we were together for meals and after work for a beer or two and a game of snooker, but usually tiredness would put you quickly to bed,” remembered Nye.

“Unlike all their other albums where I spent most of the time in the control room, at the Manor there was tons to do if you weren’t recording,” added Nick Huckle, who was in charge of the band’s equipment. “Steve, Rich and I spent a lot of time playing snooker in the games room.”

With Rob Dean’s departure still fresh, and mounting commercial pressure from Virgin, the band knew the end was nigh.

“We started from the feeling that this would become our last album,” said bassist Mick Karn, who on previous albums had worked closely alongside Sylvian, but who absented himself for long periods during the recording of Tin Drum, “so we only did what we felt like ourselves. [It was] very spontaneous, and that put the frame for the whole album. That’s the strange thing about Tin Drum. It was made on instinct.”

Read more: Japan – Gentlemen Take Polaroids

“Making that album strained relations within the band considerably,’’ Sylvian recalled. “We were beginning to close off from one another, which meant that we couldn’t give musically to one another. There were differing ambitions, and I was at odds with the band.”

Relations between Sylvian and Karn were, if not hostile, then certainly not as warm as they had once been. Sylvian has been dismissive in the years since of Karn’s role in the making of the album, referring to the bassist’s participation as that of ‘a session musician’ during its recording.

The tensions were still there, it seems, at the time of the photography session for the album’s sleeve, with Karn claiming that the singer “arranged an alternative time for the session to begin”. A set of full band photos were shot, which Sylvian would later reject, on the basis that he didn’t like the clothes that either Karn or Barbieri were wearing.

In the end, the cover would feature Sylvian, sans band, in a photo taken by rock photographer Fin Costello on a set he’d been constructing for an Ozzy Osbourne shoot. All the props in the picture came from Costello’s kitchen, with the exception of the Mao print, which he’d bought in Chinatown for just 50 pence.

Japan: Tin Drum – The Reaction

When Tin Drum was released it won the band glowing reviews. In Smash Hits, writer David Bostock proclaimed that “Japan have made their best album yet” while Paul Morley in the NME wrote that “the music (un)moves with caressing precision” and that it “accepts transitoriness, yet delights in sensation.” The LP even won praise from fellow musicians, with Tears For Fears’ Roland Orzabal calling it “an absolute conceptual masterpiece from lyrics to artwork… just *everything*.”

It was to be the last hurrah though, with Japan finally calling it a day at the end of 1982, capping their career with one final live album, 1983’s Oil On Canvas. They reformed briefly under a new name in 1989 as Rain Tree Crow, producing just one eponymously-titled album.

It’s an intriguing ‘what if…’ to ponder what 80s pop would have looked like had Japan not decided to split. Tin Drum was so bold, so outré, so different to anything else before or since, that it’s impossible not to speculate where they would have gone next.

The 1980s was a classic decade for music – its only real fault is that it didn’t have enough Japan in it.

Japan: Tin Drum – The Songs

The Art Of Parties

This is a different version of the song than had been released earlier in 1981. One of Japan’s very best, it’s an arresting opener with its twittering synths and some fabulous bass work from Mick Karn. The slightly funkier 7” version of the song reached No.48 on the UK singles chart.

Talking Drum

A calmer track than The Age Of Parties, Talking Drum is typical of the album’s experimental ethos, as Sylvian sings, “I hear a voice, I hear a sound/ But nothing plays on my mind/ I take the car, I travel ‘round/ But nothing stays on my mind”.

Ghosts

Not just one of Japan’s best songs, but one of the best songs of the 1980s. Yet for all Ghosts’ fragile beauty, it was a track that signalled the end of the band; “It was the only time I let something of a personal nature come through,” said David Sylvian, “and that set me on a path in terms of where I wanted to proceed in going solo.”

Canton

It wasn’t hard to hear the Ryuichi Sakamoto influence in this haunting, Asian-flavoured instrumental. There’s a celebratory feeling about Canton, and unlike so many album instrumentals, it feels integral to the overall architecture of the record. At one point, Talking Drum was considered as a single, with Canton as its B-side.

Still Life In Mobile Homes

Side B kicks off with this eccentric keyboard and drum-led number with Richard Barbieri on fine form. Sweetly melancholic, it’s topped with evocative lyrics from Sylvian: “The sound of wildlife fills the air/ So warm and dry/ The bushland burns in this southern heat/ Like an open fire.”

Visions Of China

Released as the album’s second single, Visions Of China hit a chart high of No.32 at the end of 1981. One of the LP’s poppier numbers, it’s still a significant step up from their earlier singles, with its electrifying mix of synths and analogue instrumentation. “Stay with me/ We could learn to fight,” Sylvian sings, “Like every good boy should/ Cling to me/ We are blacked out in visions of China.”

Sons Of Pioneers

This hypnotic, atmospheric number is one of Tin Drum’s standout tracks. At seven minutes-plus, it’s an epic piece, and one that you could imagine might have influenced Talk’s Talk’s Mark Hollis. Some have criticised the song for being too long, but its unhurried pace is perfectly in sync with the album’s meditative vibe.

Cantonese Boy

Released as the fourth single from Tin Drum, Cantonese Boy peaked at No.24 in May of 1982. Telling the story of the enlistment of a Cantonese boy to the Chinese Red Army (“Bang your tin drum/ Cantonese boy/ Civilian soldier”) it received mixed reviews on its release, with Smash Hits writing that it was “a good song”, but “can’t really be counted as much more than a stop-gap measure until the boys in rouge re-unite and pen something new.”

“Every track tells a story that we never knew about the stars of the 80s,” comments Mauro, “Their choice of song, and how it’s inspired them, reveals a side to each artists that we wouldn’t normally have seen. Learning what moves and inspires the music makers themselves, and re-discovering those songs through each icon’s own distinctive style, has been magical.”

Read more: The Lowdown: Japan and David Sylvian

Steve O'Brien

Steve O’Brien is a writer who specialises in music, film and TV. He has written for magazines and websites such as SFX, The Guardian, Radio Times, Esquire, The New Statesman, Digital Spy, Empire, Yours Retro, The New Statesman and MusicRadar. He’s written books about Doctor Who and Buffy The Vampire Slayer and has even featured on a BBC4 documentary about Bergerac. Apart from his work on Classic Pop, he also edits CP’s sister magazine, Vintage Rock Presents.www.steveobrienwriter.com