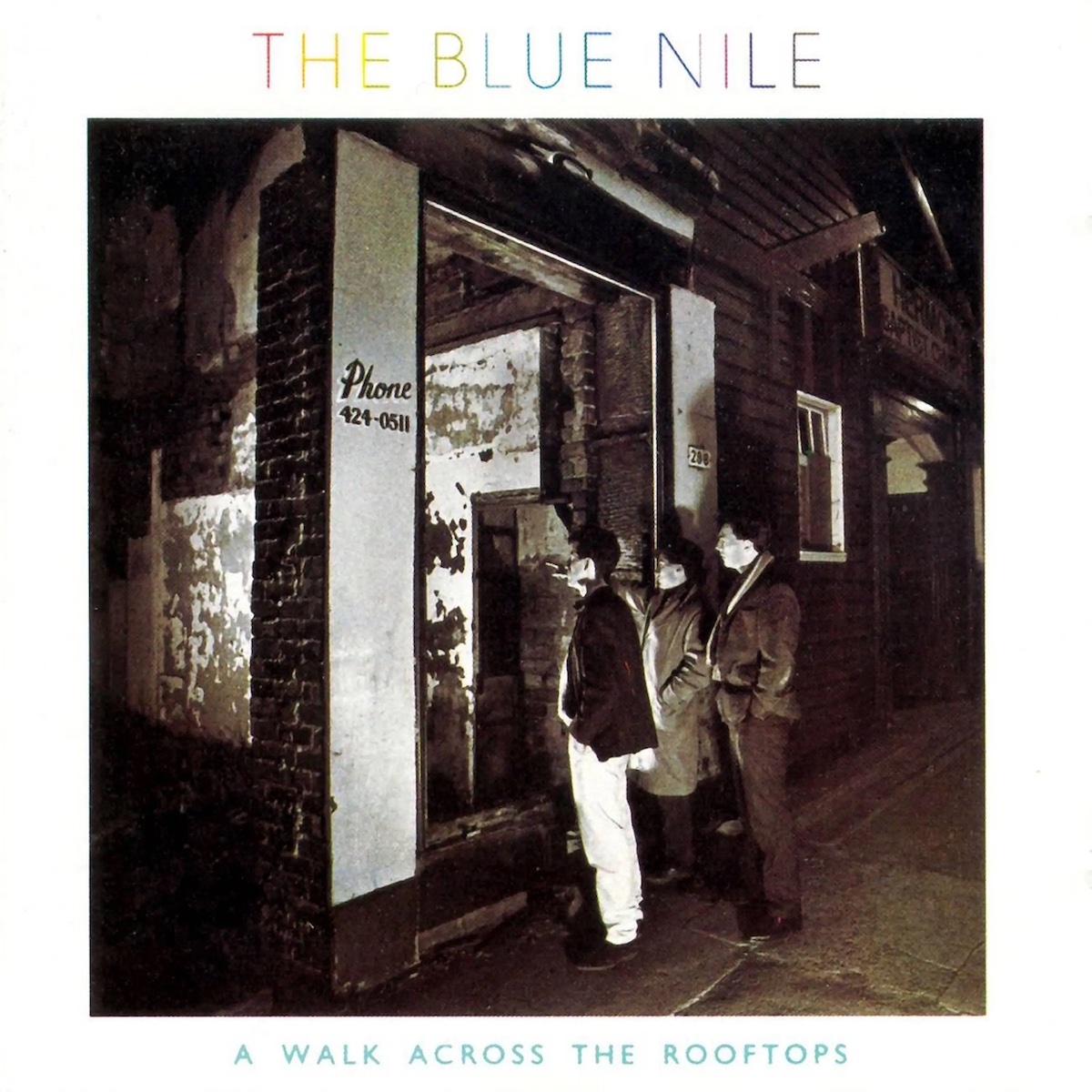

They only made four albums in 20 years, so The Blue Nile’s every record is precious. but the Scottish trio’s debut, A Walk Across The Rooftops, offered an as yet unsurpassed strain of sober but stirring synth-pop…

Being able to listen to music, and being able to talk to each other through music, is like being able to walk on air,”

Paul Buchanan once told Graeme Thomson of Scotland’s The Herald, basking in the glow of his first Top 10 hit, albeit scored as guest vocalist on Texas’ Sleep two years after his own band had released what appears to have been their swansong, 2004’s High.

“It’s like a miracle that we don’t really ever discuss. Why in the name of God can it reduce you to tears when one note goes ‘Ah’ and another note goes ‘Oh’ at the same time? Listening to melodies and going on these mini-journeys is so crucial, and it saddens me sometimes that music has just turned into a loss-leader in a supermarket.

“It’s like a miracle that has been turned into a marketing factor. I’m absolutely dumbfounded by it. Every record should be compared to silence – silence is perfect, what are you going to put on it?”

Melodies, mini-journeys, miracles and silence… These are the stuff of 1984’s A Walk Across The Rooftops, the debut album by The Blue Nile, whom Buchanan fronted over the course of four LPs. A work of delicate grace and understated yet transparent emotions, it’s hardly one of the 80s’ most attention-seeking records, yet – alongside its follow-up, 1989’s Hats – it remains one of that decade’s most cherished, casting a twilit shadow even now.

Beloved of Peter Gabriel, who’s said to have ordered boxes of it from their label for friends, it was also deemed “the best debut album of the last five years” by renowned U2 producer Steve Lillywhite. Not bad, given its initial pressing was just 2,000 copies on a label run by a small Scottish hi-fi company.

That A Walk Across The Rooftops began its commercial life in humble fashion is fitting, because it’s obsessed with minutiae.

Peppered with lyrical particulars – the title track’s “The jangle of Saint Stephen’s bells/ The telephones that ring all night”, Tinseltown In The Rain’s “There’s a red car in the fountain”, Easter Parade’s “A city perfect in every detail” – its peaceful synth-pop is suffused with a tenebrous, melancholic beauty matched by spacious arrangements and unrecognisable yet strangely familiar noises.

“We were very intrigued,” Buchanan once told the BBC’s Johnnie Walker, “by what we felt a sound could tell you visually.”

It took Buchanan and his bandmates, Robert Bell and Paul Joseph ‘PJ’ Moore, some time to find their distinctive voice. First united at Glasgow University in the late 70s, they’d begun playing together in a series of unsuccessful line-ups, their names largely consigned to history.

“I met Robert through other people who were trying to get a band off the ground,” Buchanan told Walker. “I wasn’t really thinking that. At that point I was thinking, I dunno, maybe I could go play in a bar with an acoustic guitar as a student and make some money. Anyway, I didn’t do that. Instead… we found we had some common ground, so Robert and I manfully tried to get a group off the ground for a while, and eventually PJ was one of the people in the group.”

Drummers, Buchanan confessed to Popmatters’ Jennifer Kelly in 2013, were a particular problem. “We’d rehearse for months and months and months and then do one gig and the drummer would get a job or move away. I think one day, something like that had happened and the three of us were just kind of sitting down looking at each other and thinking, ‘Ah, let’s start again. You know what, let’s just see if the three of us can do it.’”

Early experiments with a drum machine, its restrictive Latin American rhythms doing them no more favours than its human predecessors, were unsuccessful. Nonetheless, their limited means forced them to explore a more minimalist style, and they found common ground in a search for something which transcended mere entertainment.

“I turned to music because it was a way that you could get in touch with yourself,” Buchanan told Popmatters. “You could put two notes together and if it felt right to you, if it made you happy or sad, that was what mattered.”

Read more: Album By Album – Sade

Read more: Making The KLF’s The White Room

In 1981, the band recorded their debut single, the cheerful but still restrained I Love This Life. It was soon passed on to RSO Records, home to the Bee Gees, by Calum Malcolm, a young engineer.

With his own studio, Castlesound, and his own band, The Headboys – who’d had a hit for the label in 1979 with The Shape Of Things To Come – he’d first cut his teeth recording traditional Scottish music before working with early Postcard Records acts, including Josef K and Orange Juice, not to mention The Krankies on It’s Fan-Dabi-Dozi!

“I met Robert sometime around 1979, 1980,” Malcolm recalls today, “when we worked together at Castlesound on a couple of albums for Phoenix Records, a small Edinburgh record label. After a few months, Robert mentioned he was in a band called Parades, and that they wanted to record a song, which we did. I knew Ashley Newton [Head of A&R] at RSO” – he’d later mastermind the Spice Girls’ success – “and he liked I Love This Life when I played it to him, so they agreed to release it. Ashley then suggested the name The Blue Nile as an alternative.”

“No one was more surprised than us when RSO expressed an interest,” Bell recalled for Melody Maker’s Helen Fitzgerald in 1984 as A Walk Across The Rooftops arrived in stores. “Up till then we’d seen what we were doing as being quite a private thing… When RSO picked it up and we started hearing it on the radio it was quite unreal.”

“It was Kid Jensen that was playing it,” Buchanan told Johnnie Walker, “and for some reason somebody said to us, ‘It’s No.126 in the charts’. I remember thinking, ‘That’s fantastic!’ And that was a Friday, I think. Anyway, on the Monday the company was bankrupt. It wasn’t the best start.” Nonetheless, Bell told Melody Maker, “That was the turning point. After that we decided to think about writing music in the long term.”

“We had very definite ideas about the music we wanted to create,” Buchanan told NME’s Stuart Maconie in 1989, “and we realised that it couldn’t be done in half measures, so we quit our jobs and knuckled down to a whole year of concentrated rehearsing and demo-ing.”

Lining up side by side in a tiny rectangular room in a Glasgow flat, they began to develop their skills and songs. “I wouldn’t say it was punk,” Buchanan told Popmatters, “but it was certainly boho. We rehearsed the whole album through one Marshall cabinet and a borrowed amp.”

He shared similar details with Melody Maker: “That year of toil was gruelling. None of us had any money, and I mean any money, but it was worth the effort. We could have decided to be more high-profile after the RSO single, to hassle other record companies on the strength of it maybe, but we all knew the time wasn’t right.”

As it turned out, when the time was right they wouldn’t need to look for a deal. RSO had donated cash to record more songs with Calum Malcolm, whose friendship with Ivor Tiefenbrun, founder of audio equipment company Linn Products, meant some of their gear had been installed at Castlesound.

When staff visited to test some speakers, Malcolm chose to play a demo of Tinseltown In the Rain from recent sessions.

Soon afterwards, Moore told Melody Maker incredulously: “They contacted us out of the blue and asked us if we’d consider signing. They had only ever released specialist interest stuff up to then, folk and classical mainly…”

Reportedly it took the group nine months to sign the contract, and, in years to come, thanks to the increasing gaps between their albums, they’d become known for their meticulous working pace, something Bell perhaps inadvertently foresaw when he added that Linn “weren’t an overtly commercial label, and we knew we’d not be hassled into deadlines and marketing pitches”.

From his perspective, Tiefenbrun later pointed out admiringly, “Nothing would persuade them to do anything other than what they were doing,” but the band have disputed their reputation for perfectionism.

“Anyone who knows us will know how untrue that is,” Bell spluttered to NME’s Maconie despite finally releasing Hats five years after their debut, and Malcolm still concurs with Bell, putting their cautious progress down to their inquisitive nature but lack of technical ability.

“Everyone knew instinctively what the shape and atmosphere of the album should be, but without really knowing how to do it. So we worked hard at that, what colour sounds should be, and we knew when it was right. I don’t think they were slow at all; plenty of artists take far longer to make records.”

“We wanted to take it slowly and have a result worth listening to,” Bell nevertheless told Melody Maker, while Buchanan advised NME’s Richard Cook around the same time that, “Our way is just to persevere, working 16 hours

a day for weeks on end just rehearsing and trying things out.”

Two decades later he offered The Herald niceties more telling of the group’s character: “We didn’t say, ‘That’s fine, it’s good enough, let’s go out and get laid.’ We’d look at each other and say, ‘Is that right? No? Right, see you Monday.’ People talk about us as if it’s self-indulgent, but there were a lot of sacrifices. I was not in a jacuzzi. I was in a studio in East Lothian!”

Read more: Making The Sundays’ Reading, Writing & Arithmetic

Complicating matters further still – on top of visits, Malcolm reveals, by The Krankies’ “magnificent and inspiring” producer, Peter Kerr, who would drop in “encouraging us and offering sage advice on ‘the business’ of the record business!” – samplers were still a luxury, so every unfamiliar sound on the record had to be played and recorded, then painstakingly edited on tape, while “each drum part,” Malcolm stresses, “had to be manually sync’d by hitting a button on Paul’s box in time.”

Five months later, though, they emerged from Castlesound, and – thanks to Buchanan’s deeply moving delivery, the band’s startlingly bare arrangements and an overall, undeniably fastidious attention to detail – it soon became clear that, despite only boasting seven songs, A Walk Across The Rooftops was going to have long legs.

Virgin stepped in to distribute the record, and, driven by impassioned word of mouth and critical acclaim – Melody Maker called it “stunning” and “mesmeric”, while NME praised “music to shade your dreamtime in subtle colours” – sales soon defied all expectations.

No one was more surprised than the band. “I’m just astounded that it’s taken off,” Buchanan told Melody Maker.

“If it goes on for another year I’ll be surprised. I mean, we were all thinking of going back to our jobs once the LP was finished.”

By 1990, however, Irish broadcaster Dave Fanning was suggesting on air that 80,000 copies had been shifted. “It’s sold a lot more than that, actually,” Buchanan modestly corrected him. “I think we just don’t want to attract attention to any thoughts about ourselves.”

They’d be so successful at maintaining this low profile Buchanan would later admit to The Herald that “people I went to school with have recommended the records to me… We kept out of the way because I wanted people to think about a better world. I didn’t want them to be thinking about me.”

Almost four decades later, despite their best efforts, people do think about The Blue Nile, and their debut remains widely revered, a testimony to this discreet, inspired band’s dedication and determination.

Like the later work of the like-minded, if dramatically dissimilar, Talk Talk – whose Mark Hollis once famously said, “Before you play two notes, learn how to play one note… and don’t play one note unless you’ve got a reason to play it” – the record embraces peace and quiet so much they’re virtually its central focus. Its poignant sentimentality, meanwhile, skilfully, solemnly swerves the saccharine.

Dominated by the melodies, mini-journeys, miracles and silence Buchanan would later identify as the very source of music’s alchemy, it’s more than just A Walk Across The Rooftops. It is, in fact, as Buchanan himself suggested it should be, “like being able to walk on air…”

Read more: Deacon Blue interview

Read more: Making Talk Talk’s The Colour Of Spring

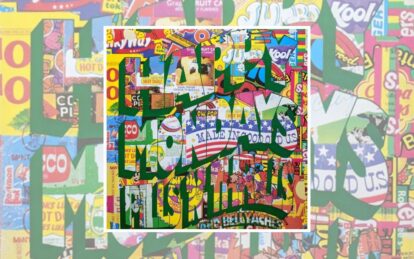

The Blue Nile: A Walk Across The Rooftops – The Songs

A Walk Across The Rooftops

With soft arpeggios flickering in the distance, interrupted by the sudden, eerie sound of grinding metal, A Walk Across The Rooftops opens in vivid fashion, setting the album’s nocturnal mood. “What you hear at the beginning is the sound of somebody walking across the rooftops,” Buchanan told the BBC’s Johnnie Walker. “I’d sit in the kitchen at night and just look out the window.

It was just the way the varying heights of the buildings were that made it possible for me just to see across the roofs.” Attended by haunting brass, stabs of bass and sparse strings, Buchanan also takes little time to establish the album’s redemptive, emotional tone, announcing after 60 seconds, “I am in love/ I am in love with you…”

Tinseltown In The Rain

Their debut’s most upbeat track, this passionate tribute to Glasgow’s magical hustle and bustle – “Here we are, caught up in this big rhythm” – offers guitars that, Buchanan later said, “made us think of traffic”, strident piano chords, sweeping strings, and one of Buchanan’s finest vocal performances, his joy irrepressible as he reassures himself, “Do I love you? Yes, I love you!”

Speaking to Dutch TV show Top 2000 A Gogo in 2013, Buchanan explained, “Tinseltown is a metaphor. It’s whatever your dream is, whatever your Tinseltown was, whatever you lost. And I think in our minds what was interesting to us was the kind of universal nature of cities… Glasgow’s obviously not the same scale as New York, but if you just shrunk it down to a corner, it could be. It could be anywhere.”

From Rags To Riches

An atmospheric masterpiece, its initially hushed character soon accompanied by mysterious noises – ticklish synth patterns, rhythms thumped out like construction work, percussive whispers – this finds Buchanan painting a picture of individuals setting out optimistically for better things. “I am in love with a feeling,” he declares, ever the romantic, “A wild, wild sky…”

Stay

A Walk Across the Rooftops’ first single, and one of Buchanan’s more enigmatic lyrics, Stay is filled with inscrutable images from its opening line, “I’m taking off this party hat”, onwards: “Red guitar is broken,” “Candy girls want candy boxes,” “Summer girls in disarray/ Can be so free and easy now.” “Stay, I think, is a more straightforwardly romantic song,” Buchanan informed Johnnie Walker. “I think maybe at the same point the protagonist is reflecting on something simple that he’s lost within himself, and that’s the grounds for his appeal.”

Easter Parade

“The last verse of Easter Parade…” says Calum Malcolm today, “isn’t that a bit of a moment?” If he’s wrong, that’s only because the entire song, built around little more than a piano, the slightest of electronic embellishments and wistfully nostalgic lyrics – “In the bureau typewriters quiet/ Confetti falls from every window” – is heart-stoppingly beautiful. “It’s a Sunday song, something with a stillness in it,” Buchanan told NME’s Richard Cook in May 1984. “It would be blasphemous of me to say it’s a holy song in any way, but that’s something that was in our minds.”

Heatwave

Opening in a low-key manner recalling Mark Knopfler’s similarly Caledonian Local Hero soundtrack the previous year, Heatwave soon shimmers blissfully, its quietly picked acoustic guitar like spring rain on the horizon, Buchanan’s performance monumentally soulful yet intimate. “We felt that Glasgow or Edinburgh could be synonymous with other places,” Buchanan told Johnnie Walker, “and I think in a sense that trying to imagine what someone’s life was just over on the other side of the rooftop, that was certainly a part of it for us. So Heatwave and From Rags To Riches clearly didn’t pertain exactly to Glasgow. What we were hoping to express was just common ground with other humans.”

Automobile Noise

Closing out their debut with another spartan but tender portrait of the city’s dark streets – “Exit signs and subway trains/ Twenty-four hours, statues in the rain” – Automobile Noise epitomises The Blue Nile’s effortless ability to conjure matching sounds and images. It also sounds as dogged as it does exhausted, its dominant bittersweet pathos concluding with an unyielding determination to resist the daily grind: “Walk in the headlights, walk into daylight…

Check out The Blue Nile’s website here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.