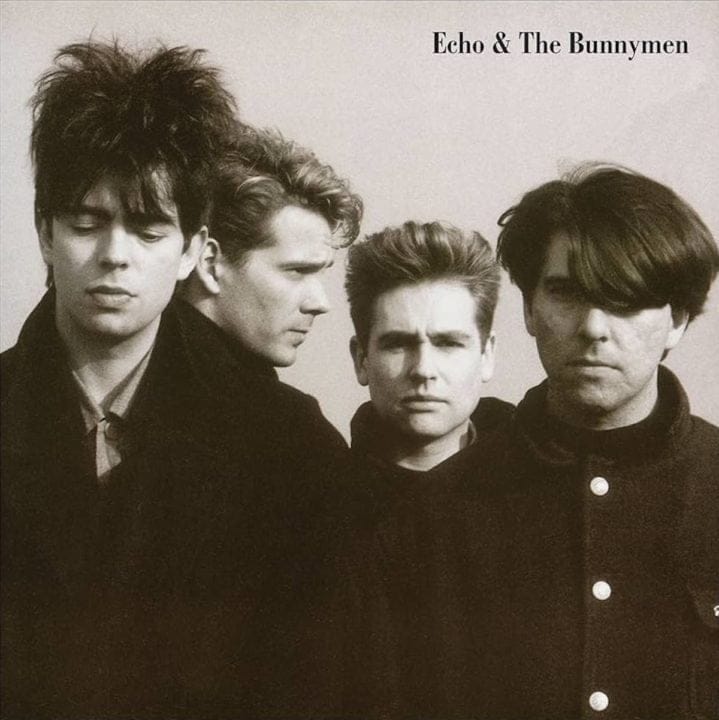

Featuring a gobby frontman with the theatrical nous of Jim Morrison, a Frank Sinatra croon and Leonard Cohen’s melancholic sensibility, Echo & The Bunnymen forged grandiose soundscapes out of punk energy and pop poetry to leave an indelible mark on the 80s…

When Cope sacked McCulloch, the self-styled ‘Mac The Mouth’ hooked up with Will Sergeant, Sergeant’s school buddy Les Pattinson, and a drum machine. The latter was replaced by Trinidadian Pete de Freitas on their debut album, Crocodiles, in 1980. The second album, Heaven Up Here, released a year later, was more expansive, more experimental than its predecessor, and broke the Top 10, despite the single, A Promise, only registering at No. 49.

Gloomier recesses of British pop

The band’s third long-player, Porcupine, was initially rejected by WEA for not being commercial enough. The Bunnymen agreed to re-record it, recruiting Indian-born American violinist L Shankar to add strings on a number of tracks, including The Back Of Love and The Cutter, their first Top 10 hit in 1983.

Fast-forward a year to what is arguably Echo & The Bunnymen’s magnum opus, Ocean Rain – indeed, the promo campaign was anchored by a quote from McCulloch, never a master of the understatement, describing it as “the greatest album ever made”. Most of it was recorded with a 35-piece orchestra in Paris, augmented by further sessions in Liverpool and Bath.

According to Sergeant: “It’s all pretty dark”. He wasn’t wrong, but it didn’t matter – with Ocean Rain, the Bunnymen became music immortals, confirming their place in the gloomier recesses of British pop.

Of course, it couldn’t last. McCulloch quit the group in 1988, de Freitas was killed in a motorcycle accident the following year, and, after an ill-fated attempt at carrying on with a new vocalist (Noel Burke), Sergeant and Pattinson pulled the plug in 1993. The Bunnymen reformed in 1997, though only McCulloch and Sergeant remain of the original line-up.

The must-have albums

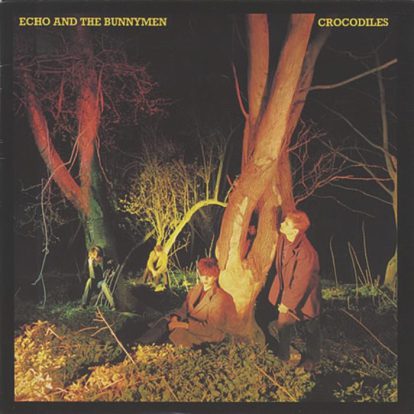

Crocodiles (1980)

The drum machine gives way

By the time Echo & The Bunnymen released their debut album, the drum machine had been replaced by Pete de Freitas. Moody and mysterious, Crocodiles was produced by Bill Drummond (who was “almost a fifth member” of the band, according to Ian McCulloch) and Dave Balfe of The Teardrop Explodes, with Ian Broudie (later of The Lightning Seeds) assisting.

The Doors influence is audible on the dirge-like The Pictures On My Wall, while PiL and The Elevators are other reference points on the likes of Monkeys and the title track. Mac remembered the sessions at Rockfield Studios near Monmouth and London’s Eden Studios with something approximating fondness.

“I can’t recall any arguments,” he pondered. “Maybe it was because we were so young, but it was brilliant.” The reviews weren’t bad either, with David Fricke of Rolling Stone gushing about McCulloch’s “apocalyptic brooding, combining Jim Morrison-style psychosexual yells, a flair for David Bowie-like vocal inflections and the nihilistic bark of his punk peers into a disturbing portrait of the singer as a young neurotic”. Crocodiles peaked at No. 17 in the UK chart.

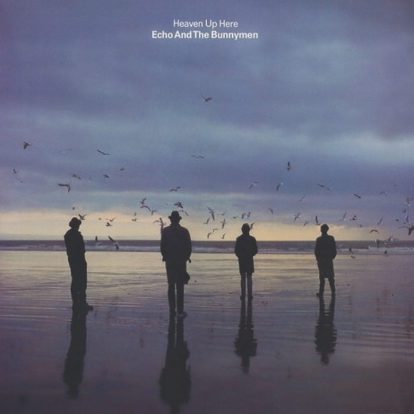

Heaven Up Here (1981)

The ambitious second album

Hugh Jones was promoted from engineer to producer on the Bunnymen’s not-so-difficult second album, which went on to win Best Album and Best Dressed LP accolades at the NME Awards, and has a place in Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, despite the band’s modest success Stateside.

Heaven Up Here is darker still than its predecessor, a glorious document of existential sadness – hardly surprising, given that Ian McCulloch had the The Velvet Underground’s What Goes On playing on a loop in his head throughout the recording. He accused Will Sergeant of being a control freak on the sessions and described Heaven Up Here as being the guitarist’s album.

Sergeant himself said: “We wanted classic sounds, sounds nobody else could get. I played guitar with a pair of scissors at one point, and I kind of banned cymbals.”

Together with Les Pattinson and Pete de Freitas, Sergeant would visit African music shops in search of instruments to devise a new rhythmic language. According to Pattinson: “It was all about not being scared to try things.”

Heaven Up Here reached No. 10 in the UK.

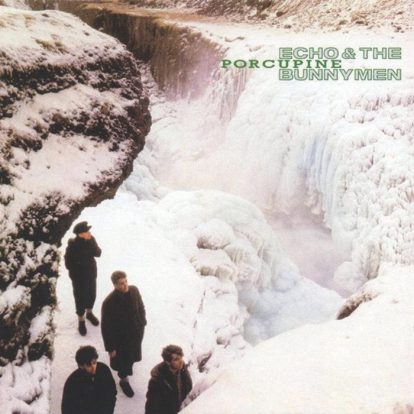

Porcupine (1983)

Who’s “uncommercial” now?

WEA rejected the original version of Echo & the Bunnymen’s third album for being “too uncommercial”. Despite Will Sergeant’s objections, they returned to the studio and re-recorded it. These sessions spawned hit singles The Cutter and The Back Of Love, both featuring American violinist L Shankar on strings (Sergeant had Shankar suggest the melody from Cat Stevens’ 1967 hit, Matthew And Son, on The Cutter).

Reflecting on the saga years later, Ian McCulloch claimed the band were “pissed off” when Bill Drummond “went in and sneakily remixed The Back Of Love and (Dave) Balfe put a keyboard thing on The Cutter”. Whatever their retrospective reservations, there were no objections from the Bunnymen when they were flogging 45s by the shedload.

McCulloch claimed Porcupine was “a classic autobiographical album, the most honest thing that I’d ever written or sung”.

Though he did go on to say: “I found the material really heavy to play – really oppressive. That’s the only reason I didn’t like the album. The songs were great, but it didn’t make me happy.”

A No.2 placing on the UK chart undoubtedly proved a balm to Mac’s woes.

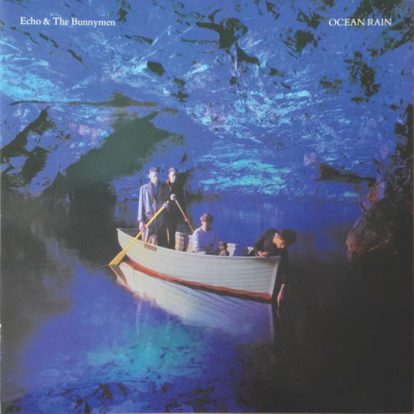

Ocean Rain (1984)

“The greatest album ever made”

Considered by many critics and fans alike to be the Bunnymen’s apotheosis, Ocean Rain was hailed (with typical bombast) by Ian McCulloch himself as “the greatest album ever made”. The band decamped to Paris for the recording with an orchestra, soaking their lush melodies in sumptuous strings, while elsewhere there were contributions from xylophones, glockenspiels and congas.

It’s variously dramatic, dynamic and deliciously doom-laden, packed with lofty ambition, but fully realised. Mac was the one who suggested Paris: “To me, I was the greatest singer in the world, never shied away from bigging myself up. I told the label, ‘Imagine how much better and inspired I’ll be if we were in France?’”

The real gold on Ocean Rain can be found on The Killing Moon, the first single. Les Pattinson recalled, “Me and Will (Sergeant) had been in Russia for a holiday, and there was this band playing balalaikas in a hotel foyer, real cheesy cabaret.

But it was fantastic. We just started messing about and the next thing is we’ve got a chorus for The Killing Moon.”

The album was the Bunnymen’s first to break the Billboard Top 100 in the US.

And the rest…

Echo & The Bunnymen (1987)

Echo & The Bunnymen’s eponymously titled fifth album (it was originally supposed to be titled The Game) would be their last for 10 years and also their final outing with drummer Pete de Freitas, who died two years later in a motorcycle accident, at the age of 27.

It was produced by Laurie Latham in Germany, Belgium, London and Liverpool after an aborted attempt at recording with Gil Norton, and sounds like a band on autopilot. The strings are supplanted by excessive keyboards, the verve capitulates to ennui and the songs are just plain dull.

Ironically, Echo & the Bunnymen (frequently referred to as “the grey album”, though McCulloch prefers “the ‘loss of grey matter’ album”) gave them their biggest success in America. But Mac wasn’t alone in wondering, “Where was the Bunnymen we all loved?”

Evergreen (1997)

The comeback album after the 1990 Noel Burke-fronted Reverberation in the wake of Ian McCulloch’s departure and the band’s dissolution in 1993. Mac had reached burnout, needed fresh impetus and wanted to work with his old muckers again.

The reunion was “like a new lease of life”, according to Les Pattinson. Anchoring a robust set is the single Nothing Lasts Forever, described by McCulloch as “the most important song I’ve ever written” and featuring backing vocals by Liam Gallagher.

And the strings were back – Adam Peters, who had worked on Ocean Rain, wrote the arrangements for the London Metropolitan Orchestra. Understated and sublime, Evergreen is a triumphant return for the Bunnymen’s founding members, McCulloch, Will Sergeant and Pattinson, though it would also represent the bassist’s swansong.

Siberia (2005)

With Ian McCulloch and Will Sergeant now the fulcrum of the band, Hugh Jones was back behind the desk on Siberia – an album some say was Echo & the Bunnymen’s best since Ocean Rain (even though it didn’t trouble the charts) and a personal favourite of Mac’s (“better than Porcupine, and I prefer it to Heaven Up Here”).

There’s a contemplative tone about the collection, especially on Parthenon Drive, and echoes of once-upon-a-time modest greatness (All Because Of You Days and Everything Kills You). Siberia is also where Mac confronts his depression in a more overt way than before.

Sergeant’s guitar is very much front and centre on this album – there are an estimated 90 different guitar parts, most of them doubled – and it’s this, according to McCulloch, that gives Siberia “more bollocks” than its predecessor, 2001’s Flowers.

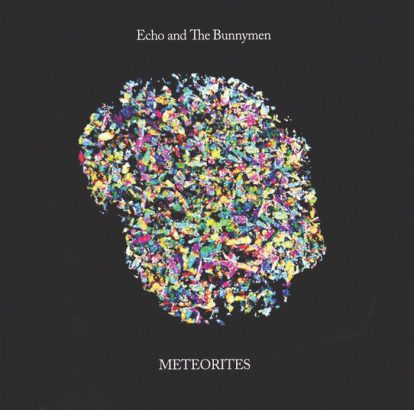

Meteorites (2014)

Echo & the Bunnymen’s 2014 release was produced by Youth, formerly of Killing Joke, who also plays bass, and Andrea Wright. Ian McCulloch wrote several of the songs on bass guitar; four of them were finished in a day.

“It sounds so different. I wasn’t thinking chordally or the way I was used to writing songs, but by doing this it reminded me of Talking Heads. It reminded me of our early Bunnymen stuff, that kind of pulse,” he said.

The title, according to Mac, was indicative of “what Echo And The Bunnymen mean and are meant to be – up there in heaven, untouchable, celestial, beautiful and real”, and the sleeve design features the Zagami meteorite, a 40lb rock all the way from Mars. A solid rather than spectacular addition to their oeuvre, Meteorites still possesses moments of grandeur, not least on New Horizons.

Read more: Essential Stone Roses songs

Read more: Happy Mondays interview

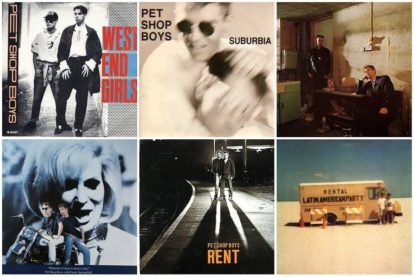

The Essential Singles

The Back of Love (1982)

On the chopping block

First aired as part of Echo & The Bunnymen’s fourth John Peel Session on BBC Radio 1, The Back Of Love was originally titled Taking Advantage. The single version, produced by Ian Broudie (under the pseudonym Kingbird) at Trident Studios, London, in early 1982, and featuring L Shankar on strings, gave the band their first Top 20 hit – just, at No. 19.

By the time it appeared on Porcupine the following year, the track had been remixed by manager Bill Drummond, much to Ian McCulloch’s chagrin. The enigma that is McCulloch sings about being in the grip of both self-doubt and selfism over a strident riff that segues into a swoonsome chorus.

The Cutter (1983)

Spare us

Porcupine was recorded at three locations, Rockfield, Trident and at Amazon in Liverpool and the atmosphere on the recording sessions was, to coin a euphemism, fraught – or, as Les Pattinson put it rather more bluntly, “There was no diplomacy in the band. It was either all-out war, or you just shut up and became a dummy.”

Ian McCulloch had an idea for The Cutter, played it for producer Ian Broudie and asked him to pretend he’d been the source. Why? “Because if I showed it to Will (Sergeant) and that, they’d say they didn’t want it. There was a lot of hiding stuff because I couldn’t be doing with them thinking there was a one-man conspiracy going on.”

Oh, dear. The song itself is a perfect union of East and West, L Shankar’s strings igniting Mac’s pleas to “Spare us the cutter” on a melody that is relentlessly spellbinding.

The Killing Moon (1984)

Fate up against your will

The greatest song ever written, according to the reliably modest Mr McCulloch – “about everything, from birth to death to eternity and God. It contains the answer to the meaning of life.” So all that existential angst has been for nothing? Mac wrote the lyric quickly, almost unconsciously, played David Bowie’s Space Oddity backwards, then fiddled about with the chords.

From Will Sergeant’s point of view, it was a trip to Russia “that fed into The Killing Moon”. He and Les Pattinson returned home inspired by balalaika bands, hence the “rumbling, mandolin-style bass thing” you can hear.

“During the recording we went for a curry round the corner, and when we came back, the producer had found this twangy thing on tape that I’d done while tuning the guitar,” he happily admitted. “It became the best-known guitar line in our entire catalogue.”

Seven Seas (1984)

Painting the whole world blue

Let’s face it, Echo & The Bunnymen don’t often do frivolous. If they were a film, they’d be arthouse black and white, austere and aloof. Seven Seas represents their nod to the mainstream, their embrace of primary colours, shot through with a strain of surrealism. It’s a nursery rhyme, a fairytale, a cryptic love song, beguilingly beautiful – or beautifully beguiling, if you prefer.

Favourite fingers, cavemen singing, fresher feeling, burning bridges, smashing mirrors – all strange life is here, as Ian McCulloch pronounces proudly, gladly on the refrain, “Seven seas/ Swimming them so well/ Glad to see/ My face among them/ Kissing the tortoise shell”.

It’s the Bunnymen’s feelgood number, light relief from the portentousness. The single was flanked by a live cover of fellow Liverpudlians The Beatles’ All You Need Is Love. Too much happy on one disc!

Bring On The Dancing Horses (1985)

From Russia with sagacity

The only new single to be included on Echo & The Bunnymen’s singles compilation Songs To Learn & Sing, Bring On The Dancing Horses is a Russian proverb, a rough translation of which suggests that when things fall apart, why not have a bit of the circus in there as well? Like Seven Seas, it’s the Bunnymen at play with both words and melody.

“Jimmy Brown/ Made of stone/ Charlie Clown/ No way home”, Ian McCulloch intones over shimmering guitars and a heavenly harp. One writer, Aaron Franz, reckons it’s “about the alchemical process.

It’s alluding to the present phase of the Great Work, which is an ages-long process of human progress/evolution.” Wonder if Mac knows that?

Nothing Lasts Forever (1997)

Northern soul brothers

Ian McCulloch had Nothing Lasts Forever in his locker “in various forms” since 1990. When he presented it to Will Sergeant and Les Pattinson, their reaction wasn’t what he’d hoped for.

“Will said, ‘It’s a bit pretty’, and I thought, ‘You fucking idiot, that’s like calling The Killing Moon a bit beautiful’. To me, it’s the most important song I’ve ever written, because it takes me back to being taken seriously, and it’s one of the best songs of all time.”

Oasis were in the studio next door, working on Be Here Now. “Liam came in and listened to it, and he had ideas for tambourine and a backing vocal, and we thought, yeah, we’re having that. He was spot on. It really made that song great.”

Read more: Pete Burns – his final interview

Only for the brave

Reverberation (1990)

Following the departure of McCulloch and the death of de Freitas, Sergeant and Pattinson assembled a new line-up for the sixth album, featuring ex-St Vitus Dance frontman Noel Burke. Proof, if it were needed, that Mac was indispensable.

What Are You Going To Do With Your Life? (1999)

One review said it had “all the appeal of a discussion with a career advisor”, while Sergeant claimed it was McCulloch and their manager “doing something that didn’t involve anyone else”.

Read more: The Smiths – The complete guide

Read more: The Lowdown – Morrissey

Need to know

- A popular misconception is that the ‘Echo’ in Echo & The Bunnymen was the name of the drum machine used when they started out. Guitarist Will Sergeant explained: “We had this mate who kept suggesting all these names like The Daz Men, or Glycerol And The Fan Extractors. Echo & The Bunnymen was one of them. I thought it was just as stupid as the rest.”

- On their 1978 debut at Eric’s Club in Liverpool, Echo & the Bunnymen played a 20-minute version of Monkeys, which was entitled I Bagsy Yours at the time.

- Echo & The Bunnymen songs are much favoured by those who compile film soundtracks. Bring On The Dancing Horses features in the movie Pretty In Pink, while The Killing Moon can be heard in Grosse Pointe Blank and Donnie Darko, and their cover of The Doors’ People Are Strange pops up in The Lost Boys.

- In 1994, a year after Echo & The Bunnymen disbanded, Ian McCulloch and Will Sergeant released Burned under the moniker

Want more from Classic Pop? Try a print or digital subscription for just 99p and access our exclusive perks and benefits. Find out more here.