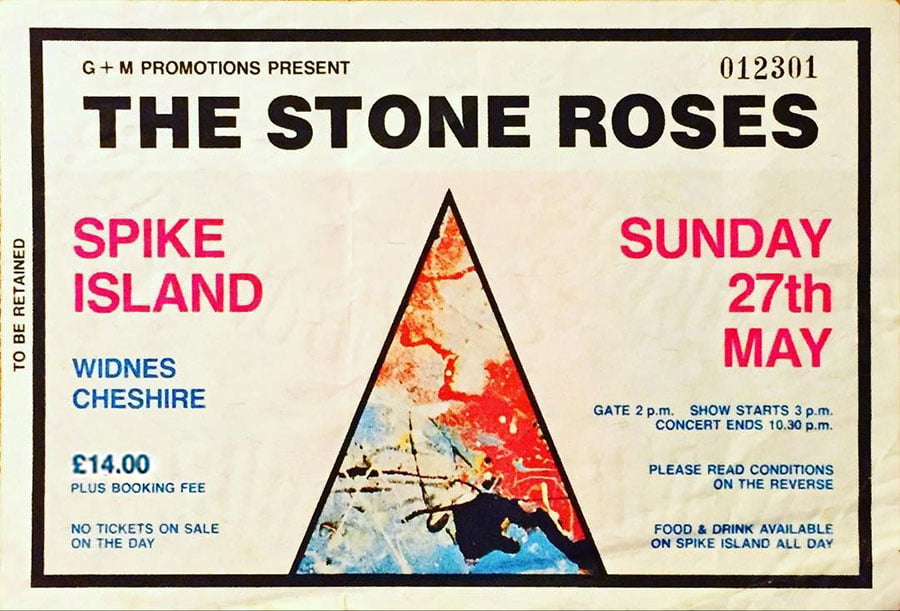

In 1990 The Stone Roses seemed on the verge of global domination when they staged their now-legendary Spike Island gig. But what’s the truth behind this most mythical of all-dayers? Classic Pop meets some famous fans who made it to this most totemic of events for ‘The E Generation’.

Before the internet had flickered into existence, nobody had the chance to Google ‘Spike Island’. For those baggies who’d thirstily paid their £14 for a ticket to The Stone Roses’ first gig of 1990, that name sounded thrillingly provocative. What exactly was Spike Island? Was it a real island? Do we have to get a ferry there? And where did the ‘Spike’ come from?

Back in 1990, few people outside the redbrick town of Widnes in Cheshire had heard of Spike Island (which wasn’t technically an island as you could walk to it via a series of footbridges). To those in the know, this reclaimed chemical waste site, ringed as it was by hulking great factories and ominous cooling chimneys, hardly evoked mystery and glamour.

Yet to a generation of music fans it’s a name irrevocably tied to The Stone Roses. As singer Ian Brown toyed with an inflatable globe up there on the stage on Sunday 27 May 1990, few were in any doubt as to what the gesture meant. This was a band with the world in their hands. It would only go downhill from here.

The Stone Roses, in the summer of 1990, had their pick of where to stage the biggest gig of their career. But it wasn’t the band’s style to shoot for the obvious. “We wanted to do something outside the rock’n’roll norm and do it in a venue which had never been used for that sort of thing before,” Ian Brown told the NME in 2010. “This was back in the days of raves, remember. We started out doing warehouse parties and still had that mentality where we wanted to play different venues. We wanted to play places that weren’t on the circuit.”

Truth is, staging this behemothic, epochal gig at a former toxic waste dump came as much from their chaotic, wildly capricious manager (step forward Gareth Evans) than it was a middle finger to the rock’n’roll establishment. Evans was, in writer John Robb’s words, “the last of the old school managers making it up as he went along”, a manic, volatile huckster more unhinged than the band that he was managing.

It was Evans who decided on Spike Island as the location for the Roses’ most ambitious gig to date. After scouting a dizzying array of quarries, caravan parks and speedway tracks (talk of a gig outside Buckingham Palace proved typical Evans bullshit), he settled on this reclaimed waste dump near, as it happens, to where he lived.

It had been just over a year since the Roses had dropped their debut album, an LP of shimmering beauty that seemed to be as beloved by pilled-up ravers as by the pale-skinned C86 kids. Spike Island was hyped as the ultimate coming together of rock and rave, a glorious single-day event that would bottle everything that ‘Madchester’ was about. Albeit 26 miles from Granadaland.

“There was definitely a sense of event, with a capital ‘e’, you might say,” says Dave Haslam, Haçienda DJ and a regular warm-up disc-spinner for the Roses. “It did feel like a great gathering and a celebration of that crossover between indie guitar music and the exhilaration of acid house.”

Dave Haslem. Photo by Matt Squire

“Everyone was so excited about it being such a pivotal day, adds writer and broadcaster Jon Ronson, who attended the gig in the company of Stone Roses guitarist John Squire’s brother Matt. “There were a few gigs at the time which we all realised were sort of pivotal. One was when the Happy Mondays played at the G-MEX in Manchester and Spike Island was the other.”

“I travelled on a coach full of Stone Roses fans from Oxford,” recalls Guardian writer and former Select editor John Harris. “We had no idea about what Spike Island was, other than it was near Widnes, and sounded kind of green and pleasant. All I remember of arriving was the coach parking on a dusty, gravelly patch of ground next to other coaches and buses, and a lot of uncertainty about whether the gates were open yet.

”The thing that runs through all this is how excited and keyed-up everyone was. To have complained or moaned about anything would have seemed inappropriate. This was an adventure, and it still felt like being part of something not everyone knew about.”

To whip up the needed media frenzy, Evans arranged for the band to meet the press at Manchester’s Piccadilly Hotel the day before the gig. It was a calamity. Never the most garrulous or media-friendly of bands, the Roses’ studied insouciance only served to antagonise the assembled journos.

“People were shouting, it got very tense,” says Ronson. “All these journalists had travelled over from America and The Stone Roses were just sitting there being deliberately monosyllabic and taciturn. I remember one US journalist yelling, ‘We’ve come all of this way, you’re being so rude!’”

Given the sky-scraping levels of excitement the next day, a sign greeting the near-to-30,000 fans seemed almost designed to piss on the party. “No cameras, no tape recorders, bottles, cans,” it read like a particularly stern headmaster’s note, while also warning “Danger – Deep Water”.

The revelry had already begun hours before the gates opened. With hundreds already on the island, car boots were opened and fold-out chairs unfurled as pills were popped and joints were rolled. Specially-made compilation tapes blasted out tunes as the sun-soaked throngs waited.

When the gates finally opened, fans found that any food and drink they’d brought were banned on-site, as security guards seized anything from six-packs to sarnies. Once inside, it also soon became clear that there was an unsettling lack of toilets and food. There was also the fact that the Roses weren’t even due on until nine in the evening.

Read more: Top 20 80s house hits

Read more: The Bristol sound

“It was at the end of May and we needed the light to fade before the Roses went on,” says Dave Haslam, “just to create an extra sense of atmosphere. They couldn’t really go on any earlier in the day.”

Since their earliest headlining gigs, the Roses had snubbed the idea of support bands, instead preferring DJs to fizz the crowd up. Haslam was one of the DJs on the day, working alongside Paul Oakenfold, Frankie Bones and Dave Booth.

“We played as if we were playing at a party,” he remembers. “We weren’t warm-up background DJs, we were supposed to be part of the entertainment.”

Bob Stanley, otherwise of St Etienne, was a writer for Melody Maker at the time and a Roses superfan, first seeing them, along with just 30 other people, in February 1989 at Middlesex Polytechnic. That August, he was one of the 4,000 who caught them at Blackpool’s Empress Ballroom and a few months later was part of the 7,000-strong crowd at Alexandra Palace. The week before Spike Island, he’d been with them at a warm-up gig at a meat warehouse-turned-youth centre in Stockholm. “The best is yet to come,” he wrote confidently in Melody Maker.

“They were absolutely my favourite group,” he tells Classic Pop. “But Spike Island itself was a pretty awful location. By the end of the day you’d touch your hair and there was a coating of plastic on it [from the pollution]. It was pretty gruesome. But it was definitely one of those things that, while you were there, you were aware that you would be able to say to people you’d been at Spike Island. That was almost more important than actually what was going on.”

Bob Stanley

Bands like the Roses weren’t supposed to play gigs in front of tens of thousands. In 1990, it only seemed to be the Durans, Bon Jovis and INXS’ of the pop world that did that, not a bunch of surly raggamuffins from the wrong side of the tracks. In March, Madchester comrades the Happy Mondays had played the 14,000-capacity G-MEX, the first sign that indie/dance culture was blowing up, but Spike Island was another level of ambition, even if the apocalyptic location was one that would have given Harvey Goldsmith a coronary.

“Sounds, the NME and Melody Maker were definitely stoking the sense of build-up,” says John Harris. “It was the first time a group you’d read about in the weekly press and heard on night-time Radio 1 had done anything that big. Just seeing that many people who dressed alike, and knew the songs was quite a mind-blower: a real ‘this is our time’ feeling.”

Despite talk of the Roses dropping in via helicopter, the dry reality is that they arrived at Spike Island in a rented minivan driven by tour manager Steve ‘Adge’ Atherton. As the car passed the entrance, the band spotted a gaggle of kids attempting to scale the fence. Digging into their pockets, they handed Adge a wad of John Squire-designed tickets to give to the youngsters. “That’s a present from the band,” he told the kids. “Enjoy yourself.”

“It was a natural progression for that band, to get bigger and bigger,” says Adge, who had been with the Roses since their earliest days. “It didn’t matter if it was the Empress Ballroom or Crystal Palace, anywhere like that, you just knew it was a progression.”

During the afternoon, the weather was a festival organiser’s dream. With temperatures pushing into the 20s it seemed as if God was smiling on The Stone Roses that day. But as dusk approached, strong gusts of wind coming off the River Mersey arrived.

As there’d been no support band, fans had no idea, until the Roses came on, how poor the PA system was, another blunder courtesy of the helter-skelter management of Gareth Evans. “There was always chaos around The Stone Roses,” says Haslam. “In terms of everything from what time they should go on stage, who does the merchandise, who runs the bar, how do they get there. The chaos seemed to be part of that era.”

At 9pm, the band sauntered on stage, as the crowd roared. “Time, time, time, the time is now, do it now, do it now… now…!” a clearly stoked Ian Brown cried before the band launched into I Wanna Be Adored. They played 16 songs in all, including the then-new single One Love, and finished with the by-then traditional I Am The Resurrection freak-out. It lasted 90 minutes in all.

Sadly, there’s little record of that performance. All that exists of that May 1990 set was recorded on a foggy, amateur-level camcorder. A camera crew from Central Music TV were ready to film the whole thing, but, for whatever reason, were told to stand down at the last minute.

Few fans seem to agree on how good or how bad the gig was. For some, it was life-changing. For others, especially ones who were stood in the wrong place, it was a colossal dud. The sound was so dismal, someone shouted, “Turn it up!”

Read more: Top Stone Roses songs

Read more: Making The Stone Roses’ debut album

“It wasn’t their best,” remembers Bob Stanley, who was positioned towards the back of the throng and struggled to hear the band. “Blackpool the year before was mind-blowingly good but Spike Island just felt a bit tired. The wind wrecked the sound.”

“Go to any gig today and everyone watches it through the lens of a phone,” says Adge. “I think people at Spike Island looked at it through the kaleidoscope of acid or ecstasy and that’s why there are so many different comments. I personally had a fantastic time – I blew up the globe that Ian held out in his hand, from behind the amplifier, and I had a belting night!”

Adge

As the Roses ambled off stage, and fans began the walk towards the exit, Bob Marley’s Redemption Song filled the field.

“Ian had requested that I should play it at the very end of the gig,” recalls Dave Haslam. “It was one of his favourite songs and very appropriate because there was a very positive vibe around at that time.

However disappointed people might have been by some aspects of the gig, in general the audience knew they’d witnessed something very special that was going to be part of the folklore of their generation. As people were leaving, they were in really good spirits and feeling very positive.”

The positivity didn’t quite extend to the band themselves, however, who found themselves locking horns with Evans after the gig.

“They had a row with him about the fact that he was selling some Reni hats,” laughs Adge. “They were more bothered about that. But they seemed happy about the gig. If it was crap, you’d know about it.”

It was Adge’s job to motor the boys back to Manchester, where they ended up at one of Evans’ many nightclubs. Despite playing for 90 minutes and earning their manager untold thousands, they were irked to discover they weren’t even allowed a drink on the house. “The snide c*nt tried to charge us for a can of lager,” grumbled bassist Gary ‘Mani’ Mounfield.

Spike Island should have been where it all exploded for the Roses. In just 18 months, they’d gone from playing to 30 people to 30,000. The major labels were circling, waving multi-zero cheques under their noses and The Rolling Stones were practically begging the band to support them. But in the narrative of The Stone Roses, Spike Island was where it started to go wrong. Their next single, One Love, was released to shrugging reviews and they then disappeared for five years.

“I still think that at the end of that they thought the world was at their feet because they did have supreme ambition and great self-belief,” reflects Dave Haslam.

Read more: Happy Mondays interview

Read more: Making New Order’s Technique

Thirty years on, the memories of the wind, the crappy, overpriced food, the under-powered PA, the fine rain of plastic and the somewhat colourless performance by the Roses seems less important than the fact that it actually happened.

Culturally, Spike Island looked like it was the beginning of something important and world-changing, but it was more like the end. The Roses went underground, the Mondays became engulfed by the brown, and the Haçienda had gone from musical mecca to gun central by 1990, closing its doors, albeit temporarily, in early 1991.

“The deterioration from the high point was pretty quick,” says Haslam. “I think everything that happened after that point was second or third generation.”

Spike Island marked the end of an era for the Roses, but it was also the beginning of a new one in terms of indie bands playing to vast crowds. Six years later, Oasis, whose principal songwriter had been there in Widnes in 1990, would play Knebworth House in Hertfordshire in front of 250,000 people, with Noel Gallagher even inviting a flu-ridden John Squire up on stage to sprinkle some six-string magic over Champagne Supernova.

Fact is, Spike Island was both a holy mess and a triumph, an era-defining shambles that remains a proud ‘I was there’ boast for the 30,000 people that turned up that day. “It was totemic,“ says Bob Stanley. “Everybody could say they were there. How good it was wasn’t really the point…”

Jon Ronson on Spike Island

Journalist and writer Jon Ronson was 23 at the time of Spike Island. He tells Classic Pop about his memories of that historic day…

“The first time I ever heard The Stone Roses was when I was in Frank Sidebottom’s band. Somebody in the band had a pre-release copy of the first album, and we played it in the van and everyone was like, ‘Oh my god, wow, this is unbelievable!’ I just remember sitting there quietly thinking I have no idea whether this is good or not. It always takes me a number of listens to figure out whether it’s good or not but then I became a really big fan.

“I wasn’t aware beforehand that Spike Island was a toxic waste dump, I just remember it being a bit of a hassle to get to. We had to walk a long way and I remember there being trenches which presumably is where the toxic waste would have been.

“There were so many disappointing things about Spike Island. There was no support band, it was just DJs, and it just went on and on and on for hours. You can only hear somebody yell, ‘Manchester vibe in the area!’ so many times before you never want to hear it again. The food and the drink were bad, there wasn’t enough of it, and there were big long lines.

“It was only when The Stone Roses finally came on stage that we realised, because there was no support band, that the sound system was massively underpowered. When there was a breeze you literally stopped hearing the band, it went from audible to inaudible. I remember trying to follow the wind.

“I saw the band a few years ago at Coachella and in terms of enjoying the show, Coachella was way better than Spike Island.

“It did coincide, though, with The Stone Roses being at their very peak. They looked so amazing. Also the audience, we were all like one. We’d all been to the smaller gigs, and it was like we’d all grown up together. We’d all seen them live and get bigger and bigger. That it was all our moment. Because we all left thinking, ‘Well that was a bit of a disaster’, I’m surprised that it’s taken on this mythology, but I can see both sides of it really. It was special and it was a disaster all at once.”

Spike Island on the big screen

Released in the same year as Shane Meadows’ Roses reunion documentary, Made Of Stone, Spike Island crashed at the box office and suffered some truly bruising reviews, with The Independent noting that “Chris Coghill’s dismal screenplay hobbles it from the off, whether in beg-for-tears stuff about errant brothers and dying fathers or in the potty-mouthed banter that falls flatter than Ian Brown’s voice.”

Time Out, however, did point out a saving grace in that virtually every song from the Roses’ first album appears in the movie. “Slap the closing solo from I Am The Resurrection over just about anything,” it said, “and you’ve got guaranteed uplift.” Amen to that.

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.