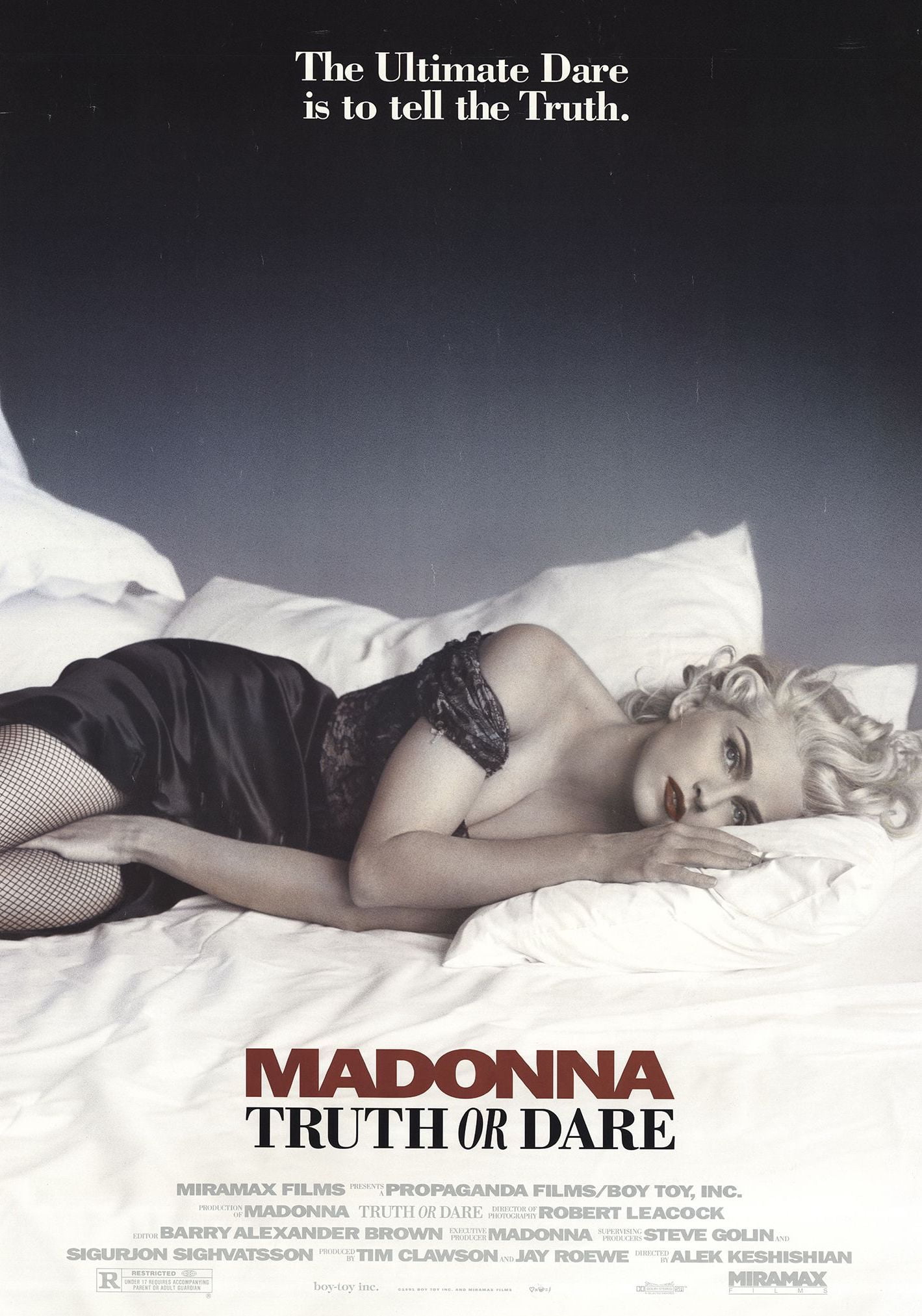

Madonna: Truth Or Dare poster

In 1991, Madonna invited cameras backstage, into her dressing room and even her bed for Truth Or Dare, which lifted the lid on what went on behind the scenes of one of the most scandalous tours of all time

It’s hard to imagine now, given that we live in an age where the concept of overexposure has been largely eradicated from the realm of celebrity thanks to reality TV and social media, the vilification and criticism that Madonna faced when she released her Truth Or Dare documentary 30 years ago.

Retitled In Bed With Madonna outside of the US due to the game after which it was named being relatively unknown at the time, it granted fans an access-all-areas backstage pass to the lives of Madonna and her touring family as they travelled the world on her groundbreaking Blond Ambition Tour in 1990.

Unflinchingly honest in its depiction of a superstar at the peak of her powers, Truth Or Dare was unlike any other music documentary that had come before it, such is its prismatic portrayal of its subject as demanding, outrageous, lonely, funny, bitchy, maternal, vulnerable and flirtatious. Presaging the raft of carefully curated ‘documentaries’ serviced by artists today, it is Madonna’s openness and willingness to be seen in an unflattering light that makes the film as much an anomaly in its genre now as it was then.

Originally envisioned as a straightforward tour film, Madonna had tasked David Fincher, director of her Express Yourself, Oh Father and Vogue videos, to commit the concert to celluloid. However, after a rumoured love affair between the two of them cooled, Alek Keshishian, a recent film school graduate who had been directing music videos for artists including Bobby Brown, was enlisted as Fincher’s replacement.

He came to Madonna’s attention after a mutual friend showed her a production of Wuthering Heights using the music of Kate Bush and Madonna which Alek had created for this thesis at Harvard. Just three days after Madonna called to offer him the job, Alek was on a plane to Japan to document the opening of the tour.

Aside from the concerts themselves, Keshishian was also instructed to shoot some behind-the-scenes footage to intersperse with the live performance for its release as a home video. Watching back what he had filmed, Madonna found herself drawn more towards the backstage reportage than the live sequences and decided to make that the focus of the film instead.

Her decision horrified her manager and record label, who believed it would be career suicide to dispel the mystique around which superstars were built. Seeing an opportunity to not only show the reality of her life on the road, but also shine a spotlight on causes that she was passionate about, Madonna was unrepentant and funded the film herself, granting final cut to Alek.

Speaking after a 25th anniversary screening at New York’s Museum Of Modern Art in 2016, Keshishian explained the importance of that decision and the artistic license it gave him.

“Final cut means nothing if you’re in disagreement with your financiers – they just won’t promote or release your film,” he said. “As Madonna had decided to fund it, I technically had complete independence. I shot over 250 hours and she never once told me I couldn’t use something.”

“I wanted to explode my own myth,” Madonna explained in 1991. “The movie is about, not only the other side of me and dispelling the preconceived notions about me but it’s also about celebrity and how we raise these people onto pedestals and make them inhuman. They are not allowed to fail, not allowed to make mistakes and they’re not allowed to have flaws.”

“Madonna really gave unprecedented access to Alek’s cameras and stripped away her pop star veneer to reveal herself as someone just as captivating while shopping as when on stage,” dancer/choreographer Kevin Stea says. “Alek did an amazing job of understanding the cultural impact of her and the tour.”

Read more: The videos of Madonna

Read more: Top pop documentaries

In a stylistic nod to The Wizard Of Oz, the film juxtaposes the black-and-white behind-the-scenes footage against stunning concert sequences, as a means to separate the person from the persona – the mono humdrum day-to-day activities act as a vivid contrast to the glittering fantasy world of the stage.

While Truth Or Dare is predominantly remembered for its backstage footage, the concert sequences are superbly shot. Filmed over three nights towards the end of the tour in Paris, Alek knew the show inside out having watched it each night for four months and was primed to capture every nuance of Madonna’s performance.

“The film is not just about me, it’s about life,” Madonna continued. “It also deals with important [themes] such as family issues – you see bits of the lives of the dancers that I work with, and within that comes something I consider a very real issue in the United States and that is homophobia. I think it’s a real problem that people don’t want to deal with and my view is, if you keep putting something in front of someone, maybe they can come to terms with it.”

Watching the film back today, in the context of how far the world has progressed in terms of understanding and acceptance of LGBT+ lifestyles, it is easy to forget how impactful Truth Or Dare was at the time.

Onscreen representation and visibility is still a much-debated issue and it is only recently, thanks to TV series’ such as Pose and Looking, that the LGBTQ+ community can see themselves represented onscreen. In 1991, it was unheard of to see gay lifestyles depicted in a mainstream movie.

“When I started editing, I felt instinctively that I wanted to get across how in Madonna’s world homosexuality was just a fact of life,” Alek says. “These dancers, who she felt so close to, they were going through that age of AIDS. There was still so much stigma against it.”

Although the Blond Ambition Tour dancers gained their own supporters among the diehard Madonna fans that attended multiple shows and met them before or after the concerts, it wasn’t until years later, with the advent of social media that they truly became aware of their influence.

Read more: Making Madonna’s Like A Virgin

Read more: Madonna On Film

“I didn’t realise at the time the impact it had on gay youth,” adds Kevin Stea. “There was no social media then so

when people contact me now and tell me I inspired them or how this movie gave them hope, I am incredibly honoured. What else can one hope for in life but to impact others positively and powerfully? I definitely think [Madonna] embracing the topic gave a generation of confused, scared young people courage and let them know they were not alone.”

“I will never forget receiving a message from a guy who said he was on the verge of suicide and that watching Truth Or Dare and seeing how comfortable I was in my own skin saved his life and gave him hope,” says Jose Gutierez. “There were others, too, people saying that because of us they came out to their parents or their friends. I never set out to save anyone’s life – at that age I was barely figuring out my own!”

He wasn’t alone. Oliver Crumes, the only straight dancer on the tour, was forced to confront his own homophobic views and attitudes towards the six gay dancers onscreen, while Gabriel Trupin, who tragically died in 1995 from AIDS-related complications, was uncomfortable with having his sexuality exposed to the world. His caught-in-the-moment kiss with fellow dancer Slam during a game of truth or dare became one of the most controversial scenes in the film.

“Gabriel pressured Madonna to remove that scene,” recalls Kevin. “She told him at the screening that ‘this will be the best lesson you will ever learn’, by forcibly outing him and sensationalising that moment. It did cause him a lot of upset and is definitely the moment I’m most conflicted about from that whole period. Though I agree with her intention and what she said, coming out is a personal journey and she seemed like a bully when she said it to him, because I know how he suffered over it.”

While he understands Gabriel’s reservations and respects how all of the dancers were on their own personal journeys, Salim ‘Slam’ Gauwloos had no qualms about the kiss being included in the film – although he was taken aback by the outrage it caused.

“I actually feel that this is one of the reasons why this film became such a big part of pop culture,” he says. “It became sort of a defining moment in gay history where two guys kissing were shown in such a natural context. I did not feel exploited as I was very comfortable with my sexuality already. Seeing everybody else make such a big deal out of this kissing scene, sort of scared me in a way. My portrayal really didn’t affect my life in a negative way. I was very happy to hear later that I was regarded as such an inspiration to so many gay guys all over the world!”

Madonna’s reluctance to skew or censor how anyone is portrayed in her movie stemmed from the fact she was also allowing herself to be shown in such an honest way. From interactions with close family and friends, face-offs with the police in Toronto and the Vatican for simulating masturbation onstage and breaking down in tears over the recent death of her friend, artist Keith Haring, nothing is off-limits.

Read more: Madonna – Ray Of Light

Read more: Making Madonna’s Like A Prayer

Hilariously, we also see her bitchy side in full splendour, be it mock-vomiting after Kevin Costner describes her concert as “neat”, gossiping with Sandra Bernhard, taking cheeky swipes at fellow celebrities or flirting outrageously with Antonio Banderas at a party, much to the bemusement of his wife. Backstage tedium is alleviated with games of truth or dare, during which Madonna declares Sean Penn as the love of her life and famously demonstrates fellatio on a water bottle.

Veering effortlessly from deeply personal to outrageous, the documentary encapsulated everything fans loved about Madonna. It also made her manager and record label incredibly nervous as to how it would be received, given that, at the time, she was one of the most controversial figures in entertainment coming off the Like A Prayer and Justify My Love videos and the tour itself. “Every moment that made you squirm in your seat, I was pressured to take out,” Madonna said. “In fact, I was pressured to forget the whole thing.”

One of the most vocal detractors was Madonna’s boyfriend at the time, Warren Beatty, who appears particularly uncomfortable in his scenes and does not hide his contempt for the cameras. He describes filming as “the insanity of doing this all in a documentary”, before chastising her for having the cameras present during a medical appointment while a doctor examines her throat. “She doesn’t want to live off-camera!” he exclaims exasperatedly – an accusation echoed by critics when the film was released in May 1991.

The film was unveiled in the US with premieres in New York and Los Angeles, both of which were events to raise money for AIDS research. It was released to mixed reviews, some praising Madonna’s bravery and honesty, others proclaiming her the ultimate narcissist and slamming the film as a deliberate ploy to shock. Most memorably, its release made the front page of the New York Post with the headline, ‘What a tramp!’, branding Madonna ”vulgar” and the ”degenerate queen of sleaze” Interviewed at the New York premiere, Madonna brandished the newspaper at the camera, announcing, “Yes, I am a tramp. And I’m proud of it!”

While the critical reception had been mixed, the film was a resounding hit at the box office, quickly becoming the most successful documentary of all time (a record it held until Michael Moore’s Bowling For Columbine in 2002) with takings of over $30 million. International success followed, with a European premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, where Madonna stripped down to customised Gaultier underwear in her usual understated fashion. Against her wishes, the film was renamed In Bed With Madonna internationally, a decision she branded “naff – not my idea”.

As well as reinvigorating the documentary genre, Truth Or Dare opened it up to a younger demographic. MTV began commissioning programming such as fly-on-the-wall series’ The Real World and MTV Diary as well as Making The Video, which granted fans a glimpse behind the scenes and leaned on stars to become more accessible.

In 2005, Madonna herself released a follow-up of sorts with I’m Going To Tell You A Secret, a film which followed her Re-Invention Tour. Although it traced a similar format, Madonna was in a completely different place in her life, a married mother-of-two heavily into the teachings of Kabbalah. A decade later, the Blond Ambition dancers’ own lives were once again under the microscope in Strike A Pose, a documentary that caught up with them 25 years after Truth Or Dare to examine how their lives unfolded.

While a documentary or a Netflix special alongside an album or tour is now standard practice, they tend to fall into two camps – the glossy concert films or trauma-driven studies where illness and addiction is overshared almost to the point of exploitation to create a narrative. In cases where the subject is dead, stars’ personal problems are picked over to the point of eclipsing their professional achievements, thus diminishing their talent. Truth Or Dare remains unique in the sense that it is simply a snapshot of pop’s biggest star, on the road, at her zenith.

“It takes a very special type of person at a very special time in their lives to want to make the kind of movie we did,” Alek Keshishian recently told the New York Times. “These days, everyone is comfortable posting on their own websites, on Instagram. They’re curating their own brand and I don’t begrudge them that. A lot of those people are better off that way. A lot of celebrities are a lot less interesting in person than you would think. There aren’t many who could pull off what Madonna pulls off in Truth Or Dare.

Read more: Top 20 girlband singles of the 80s

Read more: The story of 1981

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.