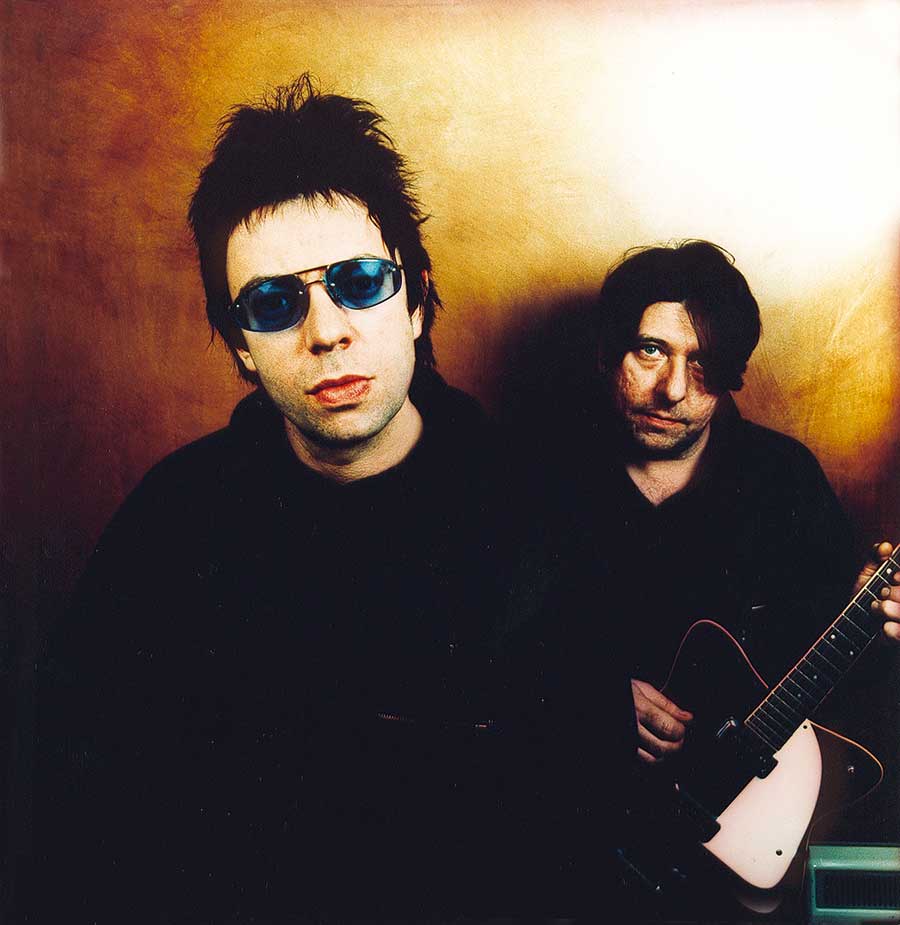

Photo by Alex Hurst

In 2018, Ian McCulloch, aka Mac The Mouth, spoke to Classic Pop as Echo & The Bunnymen returned with reworked versions of some of the most iconic moments from their glittering back catalogue. “If you’ve got a quote, say it. I’m a sarcastic bastard,” he tells us. By David Burke

Country rocker Steve Earle once said he’d stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table and declare his mentor Townes Van Zandt the best songwriter that he’d ever heard. Well, I’d stand before David Bowie’s Holy Ghost and declare Ian McCulloch the best singer ever birthed by this isle.

Bowie played characters; McCulloch is all character. His voice is soaked in the experience of a life well lived, a dance between grace and danger. His voice is honest, Scouse honest. Time spent in his company, even on a dodgy phoneline, is never dull – a freewheeling symphony of sarcasm, mischief, truthfulness, sensitivity and savvy. When Mac The Mouth talks, he sounds like a wounded but wise man full of tales and trickery. And when he sings, he still sounds like the boy who should have been king.

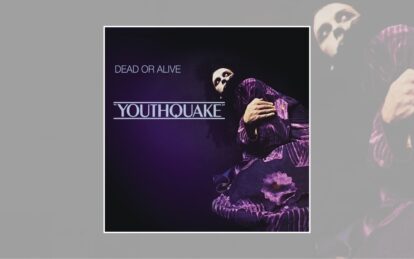

McCulloch remains the quintessential rockstar poet. Listen to the vibrant re-imagination of his back pages on The Stars, The Oceans & The Moon, songs that were peerless anyway, done again for the sake of being better. Which they are. The Killing Moon, the murkiest of ballads, cries out in a different note, a bluer note. Mac’s miserablist touchstones – Morrison, Cohen, Brel, Sinatra – are distilled in that singular, defining performance.

It will be a difficult return to the original. The whole album is a reminder not of what Echo & The Bunnymen were, but of what Echo & The Bunnymen are.

McCulloch seems humbled by the generous reception already afforded The Stars, The Oceans & The Moon, as though he can’t believe people continue to care. But why wouldn’t we? “A lot of people have said ‘congratulations’. It’s weird. I knew that it could go either way, but it seems people are interested,” he tells me, genuinely pleased. So why did he feel the need to revive a legacy?

“I sometimes find a different coat after 40 years. I think the main thing was, if I get to hear one of the old versions, I always squirm. They’re fantastic records, but I think the fact that they were sung without experience… Songs like The Killing Moon, even with the band live, it means something different to me. It never had a specific meaning, but it’s got me through my life, that song. I kind of feel I own that moon. Not Neil Armstrong’s one. But I do own that one.

“When I heard the backing track early on, it was a different version where our keyboard player took these sounds, and I thought, ‘I can sing from the moon, like I’m just standing there on my moon, singing to Earth or the universe or whatever.’ Almost like I found my place. I knew these songs were going to sustain themselves and take me on a journey, and the band, but lyrically especially.

“Like Seven Seas, I feel like I’m a sailor who’s singing a shanty psalm or something. He’s done sailing. I don’t want it to sound like an end-of-cycle thing – I’ve got more fire in my gut. Because of the way we’ve been playing in recent years, everyone plays it like it means something.”

Winning croon

He may be older now, but there’s a beguiling innocence in his delivery, especially on Nothing Lasts Forever and Rescue. “The voice is perfect for these [new] versions. With this one, I wanted to almost hear what’s inside me throat. It’s so exposed on this. I did one take on some of the songs.

“Some of them were just guides. It’s not about updating the songs so they sound modern. It’s like, that’s how I feel now. I want every single person on earth to get to hear my voice, and they’ll go: ‘He’s the best fucking voice on the planet.’ I’m certainly not the best singer, but I’ve got something that no one else has got. It’s like the opposite of Michael Bublé, or whatever. I haven’t got started on certain aspects of what I can do.

- Read more: Echo & The Bunnymen – the complete guide

“[I’m] wiser, I think. It’s like, I know the songs. I did then, but I was too busy singing them and kind of pouting. With these it was just one take, because I kind of know how to inflect without it sounding like a posy thing. I kind of let my voice just drift.

“Frank Sinatra was the master of, not just interpretation, but of knowing exactly what his voice could do. Sometimes I have competitions. I’ll write singers’ names down, like a knockout tournament kind of thing. I’ll do it with meself. So I’ll have Neil Young, Bowie, Lou Reed, Jacques Brel, maybe, purely for the voice. Even though Bowie is my favourite voice, he also does the mockney kind of stuff…

“But it’s Frank Sinatra versus Elvis Presley in the final, and meself. And depending on me mood, it’s usually Frank. But then I’m like: ‘Nah, Frank’s taking the piss – he knows how good he is.’ He makes it sound like he don’t believe it, but then he’s out with his massive knob shagging Ava Gardner with his hat on and his coat. But Elvis is doing the moves. I do Elvis when I’ve got me white kecks on. He was a brave man for wearing white kecks.”

This sort of comic diversion is Mac being Mac, the Mac that you want him to be. The Mac that’s always made great copy. Like the Mac who boasted that Ocean Rain was the greatest album ever made. It certainly might have been the greatest album of the 80s. Did he believe his boast? “No, I was talking to the head of the record company, Rob Dickins. He said to me: ‘How’s it going? What does it sound like?’ I said, ‘It’s the greatest album ever made.’

“We only had a couple of backing tracks done. It was him who went: ‘What a quote’. It was a tongue-in-cheek, arrogant kind of thing. The album didn’t go over the top. And it was strange – all those strange little songs. It was a Scouse thing, but I honestly believed it, if only for The Killing Moon being on there. I’d put it in my Top 10 albums. It’s always Marvin Gaye or Sgt. Pepper’s…. Fuck that. I mean, Marvin Gaye was good. But Sgt. Pepper’s… was shit in my opinion. It was embarrassing. Lennon was dressed like he was auditioning for a Spaghetti Western or something.

“I was on a roll anyway. I was good at it, and I could say quotes about anyone and nail them, even if I liked the fuckers. If you’ve got a quote, say it. I’m a sarcastic bastard. I’d say it to their faces and then we’d go out on the town. I have to admit that some U2 songs are great and they’re done brilliantly. Like One, I wish I’d written that – and I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For, although he’s taken about 10 hours to get to the end of the fucking song. It’s like fucking older than the Domesday Book and it’s probably going to last longer.

“But they were the direct competition – them and Simple Minds. But U2 knew how to go. That made me fucking hate them more. I used to think, ‘He’s a fucking bastard.’ Bono was on the news one time, saving Africa, literally! I thought, ‘There’s no way I’d do that.’ Adam Clayton’s me favourite bass player.”

They couldn’t hold an Amnesty candle to Echo & The Bunnymen, though… “No, I know. Especially in Ireland, people hate them over there. It’s always: ‘Alright Mac? What about that Bono twat?’ We were always getting associated with them. It was always them and us. I was like: ‘I don’t want to do all that shite on stage, based on The Boss, Bruce Springsteen.’”

A Top Of The Pops memory: the Bunnymen and U2 sharing the same Thursday-night programme, maybe their earliest appearances, doing The Cutter and New Year’s Day. “They were like, ‘It’s quiet on New Year’s Day’ – well, that’s ’cause everyone’s fucking puking up after the night before. The Cutter was Bono’s favourite song. And they loved us.”

A better Bunnyman

If Mac reckoned Ocean Rain was “the greatest album ever made”, however far his tongue was in his cheek, you won’t find him pronouncing so audaciously when it comes to The Stars, The Oceans & The Moon. In fact, quite the opposite.

“I’m not doing this for anyone else. I’m doing it as it’s important to me to make the songs better. I have to do it,” he said in advance publicity for the release. An explanation is proffered: “We had a meeting with the record company. I just said I wanted the songs to sound better.

“What I loved about that meeting, one of the main women at BMG was jotting stuff down, and that was what they chose to kind of launch the album – that he doesn’t care if no one likes it, or buys it apart from himself. The opposite to ‘the greatest album ever made’.”

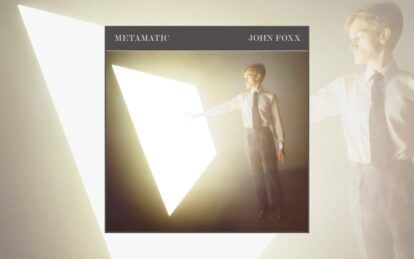

The Bunnymen – McCulloch, guitarist Will Sergeant, bassist Les Pattinson and a drum machine – formed in 1978. Pete de Freitas joined as drummer soon after. And then came Crocodiles, a debut collection that had Rolling Stone’s David Fricke going a bit gaga over Mac, whose “apocalyptic brooding” assimilated “Jim Morrison-style psychosexual yells, a flair for David Bowie-like vocal inflections and the nihilistic bark of his punk peers into a disturbing portrait of the singer as young neurotic”.

Photo by Just Loomis

Heaven Up Here and Porcupine followed, before their magnum opus, Ocean Rain. By 1987, he had quit the band, replaced by ex-St Vitus Dance frontman, Noel Burke. But it was really Sergeant and de Freitas who were to blame. At least that was the story then. But now, McCulloch insists he didn’t leave.

“I convened a meeting in a bar – they didn’t go to pubs – in Christmas of ’87. I said: ‘We need to jack this in.’ In hindsight, I needed to just not be with them, the poisonous atmosphere created by the girlfriends and wives, really.”

He admits that episode continues to bug him and that he “doesn’t like thinking about it”. So, how did Mac feel when the Bunnymen carried on without him? “Oh, it was a total stab in the back. Will phoned me up and said: ‘We want to carry on.’ I phoned him back and said: ‘You are the biggest c**t I’ve ever known and ever will know.’ It felt like I was cuckolded or something. It still feels like that. It was like suicide.

“They were like: ‘We’ll keep the name,’ and then they got some fella with the weirdest head. Freddy Krueger’s head would have been better than that! Or fucking Ann Jones – remember her, the tennis player? I didn’t speak to Will for about four years.”

Now Echo & The Bunnymen are back in the game proper, after inking a deal with BMG earlier this year, and ready for another tilt at global domination… Not that they were impelled by such ambition the first time around. “I was looking at some old photos from the Peel Sessions and stuff, and I was like, ‘How the fuck didn’t we not only be the biggest band in the world, but the richest? How come we’re not married to Miss World?!’ But we did alright. It was just we didn’t want it, particularly. It was more fun taking the piss. I always thought I’d be, not famous, just important somewhere down the line as a singer.”

Well, McCulloch got that right, at least. He is important. Very important. Perhaps Mac should get out more – “I’m just a hermit now. It’s great. I can piss in a milk bottle if needs be.”

Then it’s a return to the studio in 2019 for a new Echo & The Bunnymen album, their first set of original material since 2014’s Meteorites. “It’s very rhythm-guitar-led and there’s a lot of classy Talking Heads stuff going on. It’s a combination of lots of things. A bit more – I don’t want to say ‘funky’, but there are some James Brown-type things in there. Just anything I want to do. I love it.”

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.