In this list of the alternative David Bowie songs, we take a deep dive into his output between 1975 and 1980…

During the last five years of the 70s, Bowie transitioned between slick soul boy to Berlin-based aural pioneer – before returning to his rightful place, reclaiming the UK pop charts with 1980’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). Join us as we dive deep into the song canon to highlight some lesser-known gems…

20 African Night Flight, Lodger, 1979

Perhaps one of the quirkiest experiments Bowie had undertaken to this point, African Night Flight features a quickfire semi-rapped Bowie vocal over the top of a quirky sonic underbelly that contains a mix element referred to with tongue-in-cheek as ‘Cricket Menace’ supplied by Brian Eno, alongside distantly echoed, eerie chants. With a lyric inspired by conversations with former-Luftwaffe German ex-pats that Bowie had encountered in Kenya, African Night Flight is an unnerving, but ultimately fun piece of experimentation that contributes to Lodger’s overarching theme of wanderlust. It’s an ‘out-there’ composition that is loved and loathed in equal measure. You can guess which side we sit on.

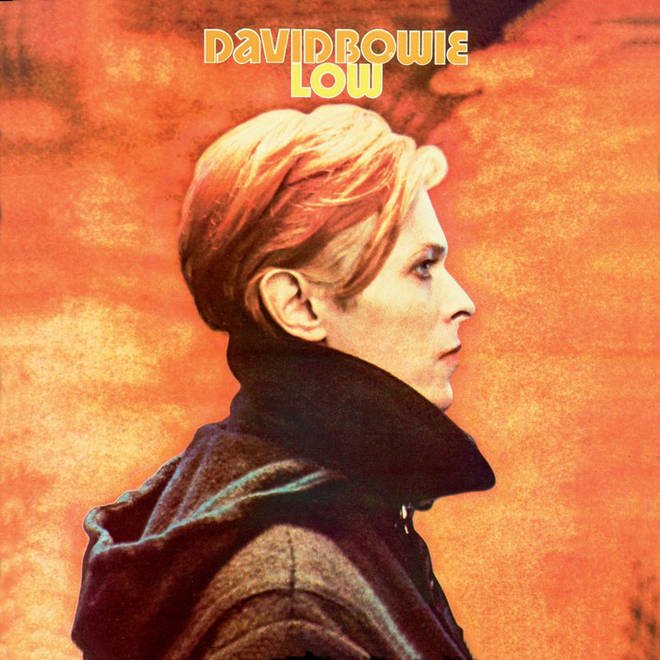

19 A New Career In A New Town, Low, 1977

The A-side of Low culminates with this dynamic instrumental that fluctuates between kinetic, upbeat art-funk to chilly, synth-dominated evocations of a desolate, alien landscape. It’s a perfect way to round out the album’s A-side and a nice lead in to the B-side’s lyric-free musical explorations. The plaintive harmonica wail adds a touch of human despair to proceedings. It’s a fair reading – particularly with the title in mind – to see this as a piece inspired by Bowie’s recent move (and culture shift) from the hedonistic, celebrity-dominated LA to the relative anonymity of Europe.

18 Crystal Japan, Crystal Japan, 1980

Used for a Japanese commercial in 1980 – though not written with that specifically in mind – Crystal Japan is a haunting, emotional hidden gem that, as with the best Bowie instrumentals, supplants vocals with melodic, and memorable, synth leads. The song was released as a standalone single in Japan while it served as the B-side of Up The Hill Backwards in 1981. Despite being released during this period, the track is more reminiscent of “Heroes”-era instrumentals.

17 Stay, Station To Station, 1976

With an infectious and urgent guitar riff provided by Earl Slick at the song’s nucleus, Stay is the rockiest thing on Station To Station and was a regular live favourite during the ensuing tour. It’s still very soulful, however, with Bowie’s vocal croon and George Murray’s funky bassline making it a peculiar hybrid of genres. Stay is a wonderful burst of energy and would return to Bowie’s live repertoire for the 1999 Hours tour.

16 Fantastic Voyage, Lodger, 1979

Lodger’s opener is a profoundly beautiful composition which serves as an indicator of Bowie’s more stable mental state. Though the song takes on quite a dark lyrical subject (imminent nuclear war), the relaxed vocal delivery during the verses and gentle piano-based arrangement lends it an air of weary resignation. It’s a vocal tour de force, with a sustained vibrato in the chorus highlighting just how great his voice had become over the 10 years since Space Oddity.

15 Joe The Lion, “Heroes”, 1977

A cluster of Robert Fripp’s sharply delivered riffs kick off this slice of new wave energy. Lyrically, it’s a sketch of the work of American performance artist Chris Burden, who put himself through enormous physical pain and risk for his art (ie, being nailed to a car, as the song references). It’s a spiky, semi-punky track that finds Bowie’s vocal at its most histrionic yet, while the subject matter once again venerates the outsider-artist figure that would be a thematic preoccupation well into the 90s, particularly on 1995’s 1. Outside album.

Read more: David Bowie in the 90s

Read more: Making David Bowie’s Let’s Dance

14 Up The Hill Backwards, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), 1980

This fascinating song seems to reference the increasing prevalence of self-help texts and motivational philosophy that had started dominating pop culture in the late 70s, as well as some of the weary resignation previously documented in Fantastic Voyage. Up The Hill Backwards is an acoustic-led piece that is among the most melodically infectious tracks on Scary Monsters… With Bowie’s chant-like vocals, unusually, not being pushed front and centre and equally mixed alongside those of Tony Visconti and Lynn Maitland.

13 Blackout, “Heroes”, 1977

Among the most unhinged performances Bowie would ever deliver on record, Blackout is a crazed juxtaposition of unfathomable cut-up lyrics and an uncomfortable, percussive arrangement dominated by increasingly versatile drummer Dennis Davis and Robert Fripp’s high-register guitar. A panicked Bowie sings, screeches, warbles and shouts his way around an improvised melody that is both abrasive and utterly captivating, particularly in the context of the album on which it sits. It’s a precursor to the heavy industrial sound of bands such as Nine Inch Nails, who cite Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy as a key influence.

12 The Secret Life Of Arabia, “Heroes”, 1977

After the emotional kaleidoscope of the Sense Of Doubt/Moss Garden/Neuköln suite, Bowie disregards his recently written rulebook and inserts a song-proper at the end of Side Two of “Heroes”. The Secret Life Of Arabia attracted much criticism at the time, as it abruptly ditches the focus on Berlin and casts its eye further afield (a precursor to the worldly scope of Lodger). It’s also more lyrically and musically restrained, despite some rather theatrical vocal inflections.

11 Subterraneans, Low, 1977

Originating as one of the compositions that would have featured as part of Bowie’s ill-fated soundtrack for The Man Who Fell To Earth, Subterraneans found a new life as the closing track of Low in vastly reworked form. Bowie would later say of the track that it represented the memories of those who remained in East Berlin after the wall was built, clinging to nostalgia for the past. Unlike the other tracks on Side Two, Bowie allows some room in the mix for his vocals; however, he delivers words in isolation, sounding like some form of private code. Subterraneans is one of Low’s finest tracks and a suitably unresolved end note.

10 Repetition, Lodger, 1979

Repetition features an unusually socially conscious lyric, highlighting the angry and abusive actions of a character called Johnny and his abusive treatment of his wife. In the context of the parent album, it serves as another of Lodger’s portraits of the repressive gender politics of the West, with Johnny’s violent frustrations stemming from regrets for not achieving what he wanted in life (see also Boys Keep Swinging). Much of Repetition’s power comes from the mechanical, deliberately lifeless arrangement and Bowie’s detached, deadpan vocal, which contains no trace of emotion. This arrangement adds to the lyric’s power and when listened to amid the aural landscape of Lodger’s colourful travelogue, Repetition’s direct, disheartening subject matter carries even greater weight than when it’s heard in isolation.

9 Word On A Wing, Station To Station, 1976

After the spiritual and existential onslaught of the masterful title track and the conscious commercial sheen of Golden Years, Station To Station’s third track, the hymn-like Word On A Wing, serves as the record’s pivotal point. Bowie (or the Duke), prostrate before God, desperately begs for salvation amid an elegant piano-based arrangement and a peaceful, heavenly guitar riff. Bowie was always suspicious of organised religion and never became a Christian. However, he later admitted that during his mid-70s period of despair, he’d started looking to a higher power to help direct him and that the ‘at-the-crossroads’ sentiment expressed on the song was real. Putting aside the thematic concerns of the song, it’s a pleasing, motivating piece of music.

8 Right, Young Americans, 1975

Perhaps the catchiest song Bowie ever wrote, this funky, intensely hooky song is one of Young Americans’ more upbeat numbers. The complex call-and-response vocals work tremendously well and Bowie’s intensely focused efforts on getting it timed perfectly were captured on video during the filming of the BBC documentary, Cracked Actor (later shown in full on the BBC’s Five Years documentary). Lyrically, it’s an uncomplicated celebration of positive thinking and is a fine example of every element of the Young Americans sound working perfectly in tandem. Because of the song’s complexity, it was never performed live.

7 Breaking Glass, Low, 1977

Low’s first song proper is as fragmentary as its title suggests, with a repetitive riff and a half-written lyric that Bowie struggled to come up with, painting a picture of a doomed relationship (an allusion to his own marital breakdown, perhaps). Brian Eno encouraged Bowie to leave this track (and others on Low) as semi-finished sketches. Breaking Glass is less than a couple of minutes in length, yet leaves an impact on the listener: it’s a great fusion of a percussion-heavy funk groove and European electronic music (Eno’s ‘wall of synths’ that the song occasionally veers into is jarringly brilliant). Bowie’s vocals take risks, too, with his phrasing and volume oscillating between deranged, bouncy and staccato at various points.

6 Win, Young Americans, 1975

As contagiously upbeat as Young Americans’ opening title track is, it’s on gorgeous second track, Win, that the listener fully realises just how completely Bowie has subsumed himself into the world of soul – and how different Bowie’s sound had become when contrasted with the rock-tinged Diamond Dogs a year before. Win concerns itself lyrically with motivation, and those in particular who, in Bowie’s words, ‘don’t do anything much’. However, it’s the lush arrangement, with soul-chorus backing vocals, glistening guitar washes and elegant saxophone that elevate Win above many of the other tracks on the record, not to mention Bowie’s spellbinding vocal performance, which underlines his newfound comfort in the lower registers. Bowie’s long-time bassist Gail Ann Dorsey stated that Win is her favourite Bowie song. Despite this, it was rarely performed live.

5 Sense Of Doubt/Moss Garden/Neuköln, “Heroes”, 1977

Though they’re three distinct tracks with quite different feels and textures, these expressive instrumentals (when listened to as they’re supposed to be listened to, in consecutive order) represent the aural equivalent of a train ride through the shell of a multicultural city, with the doomy, oppressive Sense Of Doubt leading serenely into the relative tranquillity of the oriental Moss Garden, before culminating with one of Bowie’s most expressive musical performances on the isolated and mournful Neuköln. By the last track, Bowie’s sax takes over the lead vocal role and becomes a wailing, anguished banshee in perhaps the finest sequence of instrumentals that Eno and Bowie conceived. Though Low’s second side was more colourful, the instrumental half of “Heroes” arguably works more effectively as one shifting suite of moods. Aside from the nuanced, rich mix, it’s also profoundly moving. Genius.

4 It’s No Game (No. 1), Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), 1980

Scary Monsters…’ punchy, uncompromising opener is notable for a number of reasons – the alarmed delivery of the Japanese lyrical elements by Michi Hirota, Bowie’s screamed, howling vocals and the baffling hysteria of Robert Fripp’s sequence of guitar riffs demand attention from the listener. If Scary Monsters… was Bowie reclaiming the contemporary pop landscape of 1980, then It’s No Game (No. 1) is the opening salvo – a challenge to both the theatrical snarling of the punk movement and the right-on sanctimoniousness of the protest song. The song also frets about mortality, and in particular that fame might lead to assassination, with Bowie’s lyric: “Put a bullet in my brain, and it makes all the papers”. The song’s twin, It’s No Game (No. 2), closes the record, and is a gentler, more restrained version of the same song. One of the album’s key tracks, It’s No Game (No. 1) launches Scary Monsters with gripping, propulsive power.

Read more: Making David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)

3 Always Crashing In The Same Car, Low, 1977

Allegedly inspired by Bowie’s unfortunate incident in an underground parking lot in Berlin where, in a state of inebriation, he wrote off his 1950s Mercedes, Always Crashing In The Same Car is one of Low’s standout tracks. The song also works as not just a real-life memory put to music, but as a work of self-reflection – where Bowie ‘going round and round the hotel garage’ serves as an apt metaphor for his then- uncertain and highly depressed state of mind. It features some outstanding guitar work from Ricky Gardiner, with a solo that takes centre stage in the mix (though the melody of the solo was originally whistled to Gardiner by Bowie). The rest is full of sumptuous elements, including Eno’s shimmering synth bedrock. Bowie would perform the track live for the first time 20 years later, on the Earthling Tour.

2 Teenage Wildlife, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), 1980

By 1979, Bowie’s heirs apparent were on the rise, emerging from the Bowie nights being held in clubs such as Billy’s and the Blitz, the next generation of the pop aristocracy were consciously cribbing from Bowie’s visual and musical lexicon and reshaping it in their own image. Teenage Wildlife is Bowie’s own response to those taking their cues from his body of work, the nature of the cyclic industry and an embittered warning to those in pursuit of fame for its own sake. Though the lyrics contain harrowing, distressing imagery, the wonderfully exaggerated vocal delivery, triumphant melody and Fripp’s searing guitar riff make the track one of Scary Monsters’ highlights.

1 Station To Station, Station To Station, 1976

The longest studio track in the Bowie canon is also one of his most outstanding. Unveiling the shadowy Thin White Duke character – a slick, monochromatically dressed European aristocrat who Bowie described as a “would-be romantic with absolutely no emotion at all”. Opening with a synthetic train sound before a two-note, repetitive motif heralds the Duke’s arrival. The eerie squall of Earl Slick’s guitars counterpoints the ominous march of Bowie’s tight-knit rhythm section, before the track slows down for a serene chorus. Melodically and sonically, the song is intensely rich: however, it’s in both Bowie’s towering vocal performance and the lyrical content of the song where we find, yet again, the track’s real meat – a poetic, and somewhat introspective song that longs for resolution. Once again, Bowie evokes the occult, with references to Aleister Crowley and Kabbalah, and there are references to cocaine – a drug that Bowie was growing ever-dependent on during this period, and a key ingredient in the cauldron that yielded the Duke. Station To Station is a true Bowie epic and a harbinger of his upcoming European-based experimental works. One of his finest, and most unique, songs.

Read more: The alternative David Bowie Top 2O – 1981–’93

Read more: Top 40 synth-pop songs

Read more: The Story Of The New Romantics

Check out David Bowie’s website here

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.