Milli Vanilli

For decades, pop has been littered with acts whose performances or recordings received a little help behind the scenes. From Boney M. to Milli Vanilli and Black Box to Technotronic, Classic Pop investigates how some chart stars aren’t always what they might seem… By Mark Elliott

There was a time, of course, when the artist barely mattered at all. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the song (or song sheet, from a business perspective) was what it was really about.

Acts would record their interpretation of a tune and hope their version would be the one to cut through. Even during the early years of the rock ‘n’ roll era, multiple versions of a song would chart at the same time. Michael Holliday made the UK No.1 spot with his version of Bacharach & David’s The Story Of My Life in 1958 by seeing off rival concurrent hit cuts by Alma Cogan, Dave King and Gary Miller.

As with so many things, The Beatles gradually changed everything. Suddenly, writing one’s own material was seen as a critical badge of honour and, although the stay-at-home songwriter wasn’t exactly redundant from then on, a definite hierarchy had been established.

It was a crude measure of merit. Vocalists couldn’t expect any elevated position in this hierarchy of acceptability – most didn’t play an instrument, after all – but they knew their place (and could expect some reverence if suitably surly and talented). Bands had a better look-in, but only if they knew their plectrum from their drumstick.

Near the bottom of this League Table Of Cool came the ‘studio’ act – bands that were made up of musicians drafted in for a project that was often limited in scope.

One example is The Archies, who made No.1 in 1969 with the popcorn classic Sugar, Sugar. No one could pretend that this was anything but a cartoon concoction (think a wholesome blend of The Brady Bunch, ABBA and Gorillaz). Lowest of the low, of course, was the band that pretended to play on their music. Then and now, it’s proved the kiss of critical death.

U GOT THE LOOK?

We can all guess how it happens. Producers and managers seize upon a song or sound they think will be a hit, but then need the tools to bring it to life. That’s primarily about people. Even the earliest days of modern pop PR might involve TV appearances, a promo film and plenty of press coverage. And not every session muso could carry off a look required for the increasingly image-obsessed industry.

Occasionally, of course, a credible act just couldn’t cut it for a particular release. The rush to record He’s A Rebel in 1962 led to the members of The Crystals not even singing on the single, which actually broke them in the UK.

Producer Phil Spector pulled in rival girl group The Blossoms for the session when touring commitments kept The Crystals on the East Coast of the US, far from Spector’s California studio.

No one expected studio act Tight Fit’s version of The Lion Sleeps Tonight to top European charts in 1982, but its unexpected success meant that the ensemble created for Top Of The Pops slots on previous hits Back To The Sixties and Back To The Sixties Part Two just wouldn’t do.

Hunky model/singer/dancer Steve Grant was drafted in with two attractive female vocalists, Julie Harris and Denise Gyngell, and the trio’s sexy image distracted anyone from asking too many questions. They were invited into the studio for the hit follow-up, Fantasy Island, but that was the end of their Top 40 story.

Sometimes an act can get away with it, of course. Plastic Bertrand scored a rare French-language hit in the UK with Ça Plane Pour Moi in 1978, but hadn’t actually sung a note on the smash, with the vocals being cut by the disc’s producer, Lou Deprijck.

This startling revelation didn’t come to light until 2010, when it emerged in a bitter court case over royalties. “I don’t mind saying it wasn’t my voice,” Plastic told Belgian newspaper Le Soir. “I wanted to sing, but [the producer] wouldn’t let me in the studio.”

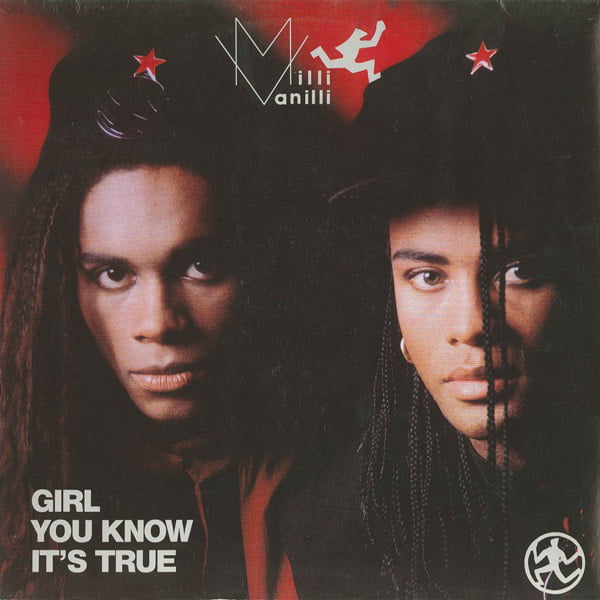

It seems the truth will always out… and never in more dramatic fashion than the infamous case of Milli Vanilli. Fab Morvan and Rob Pilatus were picked by German studio Svengali Frank Farian and the pair’s infectious hits – Girl You Know It’s True, Blame It On The Rain, Baby Don’t Forget My Number and Girl I’m Gonna Miss You topped charts around the world.

Even America took them to its heart and in 1990, the prestigious Grammy Awards named them Best New Artist. They bagged three American Music Awards and a Juno for International Album Of The Year.

That album – All Or Nothing in most markets, but repackaged as Girl You Know It’s True in North America – was made up of 13 cuts of serviceable, accessible pop/soul, but Fab and Rob hadn’t played any part in creating it.

“I didn’t realise how a producer was often more important in the business than the artist out front,” Fab told author James Arena for his book Stars Of 80s Dance Pop. “As a young person, you felt the excitement. You would be part of an incredible ride. We wanted to take that ride. We knew our life would change; we just weren’t sure how, when or where.”

No one could have predicted just how dramatic and rapid their rise would be. Within months of the single Girl You Know It’s True’s release in the summer of 1988, it was a huge hit all over Europe, with US success coming early the following year. “We fell into a trap that we just didn’t see coming,” says Fab.

GUILTY SECRET

Tied to a legal agreement that saw the pair committed to fronting out promotional appearances for the records, the increasing adulation was becoming uncomfortable. “We were up against the wall and thought by doing what they asked of us, we were getting out of the situation,” says Fab. “Instead, we were actually getting in deeper and deeper.”

Soon committed to worldwide touring and promotion, the pair felt bound together by their secret. “It appeared like we were part of this big entourage, but in reality, we were alone,” says Fab. “We began secluding and isolating ourselves more and more. From the start, we were never really cool with the idea [of being frontmen].”

Against a backdrop of escalating arguments about the direction of the project with their producer back home, Farian eventually lost patience with the troubled pair and flew to the US to confirm growing rumours that the duo hadn’t sung on the disc. The story became a media sensation and the Grammy was taken back (ahead of the pair’s alleged commitment to give it back voluntarily).

“I took it personally for many years,” admits Fab. “There is no doubt that a stigma is attached to me… Maybe I’ll be remembered for just those two words – Milli Vanilli. But I want those words to stand for a way of life – even though it’s far from easy. When you fall, you stand back up, and you move forward.”

Fab’s fighting spirit may have pulled him through, but the Milli Vanilli story has a tragic footnote: Rob Pilatus died in 1998 of an overdose (which was ruled as accidental), as the pair – then reunited with Farian – prepared a comeback album billed Back And In Attack. Following the tragedy, the recordings were canned and have never seen the light of day.

Frank Farian had form, of course. A decade earlier, he had helmed the 1970s supergroup Boney M., who had a string of huge sellers including Daddy Cool, Mary’s Boy Child/Oh My Lord and Rasputin.

Although marketed as a quartet, the group’s distinctive Europop sound was created by vocalists Liz Mitchell, Marcia Barrett and Farian. Maizie Williams and Boney M’s sole male member, Bobby Farrell, were central to the band’s image, but had little to do with its music.

“Frank had brought Bobby to the studio to try to sing Ma Baker. I think his problem was pitch, and they realised he was not going to be able to do it,” recalls Liz. “I think [Frank’s] voice is there somewhere on the records of just about everyone he produced… That may have been viewed as intrusive by not allowing the artists to shine properly.”

Although Liz would soldier on with the arrangement, Bobby eventually quit and the group’s stellar success soon faded. “The fact that Bobby and Maizie were miming pushed all the good work I did to one side and created a shocking conversation,” says Liz. “This controversy became the topic of conversation, rather than the fact that Rivers Of Babylon and Brown Girl In The Ring were two of the biggest-selling records of all time.”

DO THE MATH

There’s a theme around big sellers emerging here. 1989’s best-selling single in the UK was Black Box’s Ride On Time. That Italo-house pop smash famously sampled Loleatta Holloway’s Love Sensation and was created by Italian production unit Groove Groove Melody.

They hired model and go-go dancer Katrin Quinol as the face of the act, but crucially made sure everyone knew what her role in the project was. “When I started to figure out the situation and wanted to sing for real, it was too late,” says Katrin. “It was a lot of fun, but, of course, I’d have loved to record the songs.”

That huge international hit was part of a new dance renaissance, but not everyone was following the honesty-is-the-best-policy protocol. Technotronic got into trouble when Pump Up The Jam was credited as ‘Featuring Felly’. Felly was another model drafted in to front the record and, as it became bigger, producer Jo Bogaert wanted to push the track’s real vocalist, Ya Kid K.

“It didn’t feel right to me,” says Jo. “We all thought the public would only accept a proper band.”

Technotronic and Black Box were the start of a new era of dance when band branding became redundant. Acts could score a smash and never be heard of again. You may still recognise Son Of A Gun, U Got 2 Let The Music and 7 Ways To Love, but try to match them to Cappella, JX or Cola Boy today.

Cappella scored eight Top 40 singles in the UK, but were likely never recognised outside the Top Of The Pops studio. Corona, who had a 1994 hit with The Rhythm Of The Night and other cuts, was marketed as a solo act with Olga Souza centre-stage – but was another studio project from Italy.

No wonder, then, rumours around who contributed what continued to dog many of the day’s biggest pop acts. Bands such as A-Teens or S Club 7 that had been built around a marketing brief were bad enough, but those that weren’t even there for the recording just couldn’t be tolerated. So the reality boom of TV shows like Pop Idol began to offer fresh insight behind the scenes, silencing the speculation for good.

And those annoying dance concoctions? Well, the new breed of DJ-producer has put paid to all that. He or she can just draft in who they like. And ultimately, who cares if records now read like a lengthy blockbuster cast list? At least we know who’s who… don’t we?

- Read more: Top 20 80s B-sides

- Read more: The story of MTV

PAYING LIP SERVICE

The art of miming…

The ability to pull off a decent attempt at miming is crucial to most bands tied to a traditional promotional plan. So much so, that successful acts can still create a career without venturing near a live audience. Bananarama had been having hits for seven years before they hit a stage in Boston, US, on the first night of their long-anticipated first world tour.

In fact, the 1980s was a time when playing live was secondary to pushing record sales through video and TV. So it was a shock when Top Of The Pops decided to insist on authentic live performances in one of its periodic relaunches at the start of the 1990s. Many acts came unstuck, with Felix and Cappella routinely singled out as among the worst. Even Nirvana – though it was clearly deliberate – put in a hilariously poor showing for their Smells Like Teen Spirit appearance.

Ashlee Simpson’s car-crash slot on Saturday Night Live, when her backing track went wrong, exposed her to be miming and effectively stalled her career. And who can forget Mariah Carey’s disastrous turn at the New York New Year’s Eve celebrations in 2016? Her lame attempts to diva it through a technical failure attracted widespread ridicule.

Britney Spears left herself open to criticism in Australia when she launched her The Circus tour with a predominance of largely lip-synched performances. That also earned the Queen Of Pop, Madonna, a tongue-lashing from Elton John, when he accepted a gong at the Q Awards. Criticising her win for Best Live Act, he sneered: “Since when has lip-synching been live?” The pair allegedly made up, but it proved the self-appointed credibility police were as vigilant as ever.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!