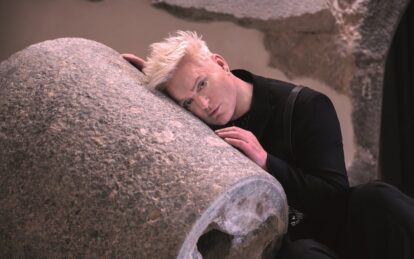

Photo copyright Sheila Rock

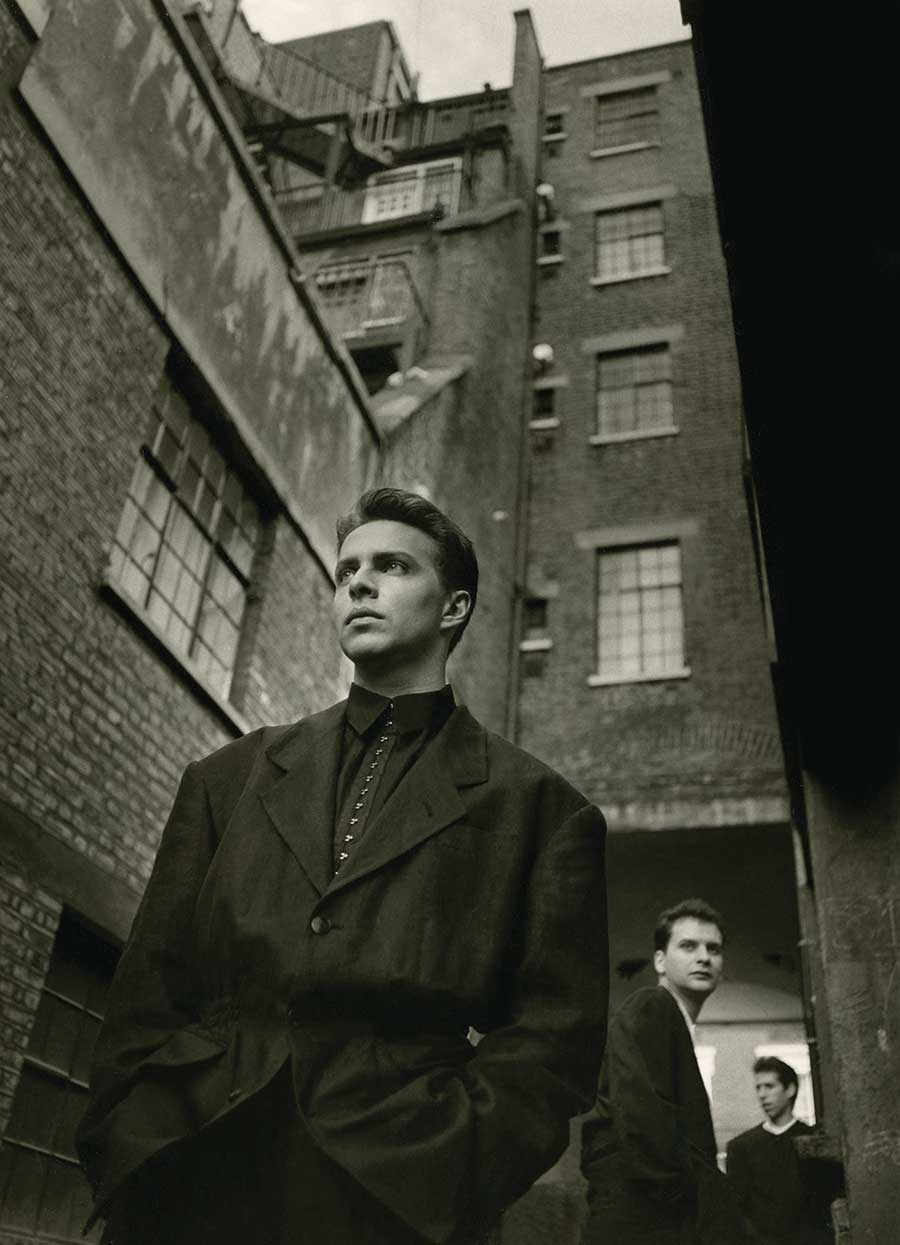

Johnny Hates Jazz burst onto the scene with their hugely successful debut album, but an impatient frontman led to a parting of the ways. In 2018 they reunited and we met with vocalist and songwriter Clark Datchler… By David Burke

“I should have been more patient, but I just wanted to get on with the next thing,” is how an older, wiser Clark Datchler reflects on the wrong-headedness of his decision to quit Johnny Hates Jazz in 1988.

The group had scored a UK No.1 album with their debut, Turn Back The Clock, and were basking in the glory of singles success on both sides of the Atlantic with Shattered Dreams, when frontman Datchler dropped the bombshell on fellow founder members Mike Nocito and Calvin Hayes.

“It was a question of: ‘Okay, what next?’ Turn Back The Clock was a pop album. And any musician that you meet or talk to will tell you that what they’re doing at that moment is the most important thing to them. So, I was very much like that – ‘Yeah, Turn Back The Clock is fantastic, but you’ve got to hear this new song. This is where we’re going’.

“I think if I had been a little more patient – I was very impatient when I was younger – I would have quietened myself and said: ‘Whoa! This has been a long road and I am privileged to have reached this point. Now where do I take it?’”

Datchler had always seen himself as a solo artist, having signed to Bluebird Records in his teens and later decamping to Los Angeles as a songwriter for Warner Brothers Music, and was “very split about staying in a band”.

He recalls of Johnny Hates Jazz’s genesis: “I had come back from living in LA as a young lad, didn’t really know what to do and answered an ad in Melody Maker to join a band, which was signed to a label, which turned out to be RAK Records. Calvin was in a band with Glen Matlock [Sex Pistols] and James Stevenson [Generation X]. They were called Hot Club. I joined as a singer.

“Basically, the head of RAK, who was Mickie Most, Calvin’s father, approved me as a singer, then signed me as a solo artist. He said: ‘You should work with a young engineer/producer at RAK, Mike Nocito, an American guy’. So, it was Mickie who put the two of us together. Mike and Calvin were doing some stuff together. Four years later, we realised we should pool our resources and create something, which became Johnny Hates Jazz.

“It felt like a good fit. All three of us were very broad-minded musically, had varied musical tastes. There was no narrowness there. In a way, we were quite a mature bunch, even though I was quite young. Mature in the sense of our musical history, and it made us quite realistic about what we were facing. You felt you were around kindred spirits, definitely.”

But even kindred spirits are not immune from the vagaries of fame and fortune, as Datchler explains: “Although we all got on well in certain ways, everyone has characteristics, and you find in the pressure cooker of that kind of success, it brings things to the surface, so it was difficult, in some ways. I think that it’s very much down to how different people react to attention – and I mean fame.

“I think that created a divergence and it wasn’t just me, but it was me as well. I take responsibility for that. You start to feel that different people want different things out of it.”

Don’t let it end this way

Nocito and Hayes were “devastated” by Datchler’s departure. “I was the singer, and that’s fine, but as far as I’m concerned, singers are 10-a-penny, especially these days. But to lose your main songwriter and your front guy is quite a blow. And on a personal level, they were gutted. But I’m sure there was a part of them that thought they would go on with Johnny Hates Jazz without me and do very well, just as I thought I would on my own.”

Neither of the above scenarios panned out. Yes, Johnny Hates Jazz carried on, with Grammy Award-winning engineer and producer Phil Thornalley replacing Datchler, but eventually split in 1992, after a second album, Tall Stories. Datchler, meanwhile, moved to Amsterdam, where he released a couple of collections, Raindance and Fishing For Souls, before returning to Blighty and basing himself at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios near Bath for most of the decade.

Photo by Simon Fowler

“When I was in Johnny Hates Jazz, one of the cool things was that you were promoting all over the world, and I became very aware of the environmental problem worldwide. It’s the one challenge we all face as people, no matter what our race, our language or our religion. I wanted to move in that direction, musically, to start articulating more of that.

“As I changed as a person, I became more spiritually oriented as a result of my environmental concerns. I started listening to music that reflected that, maybe not lyrically, but certainly instrumentally. That led me to Real World. I wanted to be around a much more broad view of what music could be, and what it could stand for.”

- Read more: Making Spandau Ballet’s Journeys To Glory

Class reunion

At the beginning of the new millennium, eco-warrior Datchler moved to the States for a second time, creating a solar-powered home and studio and studying the philosophy of indigenous people. Then, in 2009, his old bandmates got in touch.

“We hadn’t talked for 21 years. Not a sausage. I was living in Arizona. I was committed to recording a solo album with an environmental theme. Calvin called me; the two of them had the opportunity to get back together on these retrospective tours. It wasn’t my thing. I didn’t like the idea of being grouped together in this kind of nostalgia thing. I had an issue with the decade-isation of music as well. So, I declined.

“Then I started writing a song called Magnetized and realised it sounded like a modern Johnny Hates Jazz record. I contacted them again and said I would do that live side of things if we could make a new album. Then some meetings happened, and I saw both of them for the first time in 21 years. Mike and I met in a restaurant in Cambridge.

“Although you can’t say that it’s all water under the bridge – there’s always going to be a bit of baggage from the time that I’d left – it was lovely, in that it felt like we’d only seen each other a week or so ago. We got to know each other again, and I proposed the idea of a new record.”

That new record was the long player, Magnetized, recorded without Hayes and issued in 2013 to much excitement. Johnny Hates Jazz were gaining traction again when Datchler was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. By the time of his recovery the following year, the momentum had been lost.

Since then, Johnny Hates Jazz – now fulcrumed solely by Datchler and Nocito – have maintained a live presence in Britain, Central Europe and Asia. Earlier this year, they unveiled a bumper 30th Anniversary Edition of Turn Back The Clock, including an acoustic version.

Photo copyright Sheila Rock

“It’s taking a song known in one recorded form and almost deconstructing it and presenting it in a much more honest form, in some ways. There’s far fewer bells and whistles on it. Some of the gigs we’ve done in the past have been acoustic, and they’ve always been the most enjoyable ones.

“There’s something about doing it in that form – it’s just you, your instrument, your voice and the audience. Having done that a few times, and really enjoying it and liking the fact it’s just presenting the songs as they are – they stand or they fall in that environment – seeing people respond to that positively made us think it would be a lovely thing to do.”

Clock of ages

So, how does the original Turn Back The Clock sound to Datchler at a remove of three decades? “It’s interesting because, knowing the album so well, I had to have quite a bit of distance from it. But I’ve been doing a lot of performing recently, so it’s been back in my face a bit! I think it’s stood the test of time well.

“It’s difficult for me, because I was the main songwriter and I do tend to be song-oriented, but I think one of the reasons it’s weathered so well is the songs are of a certain standard.

“But also, in some ways, we weren’t too rooted in the 1980s. Not that we weren’t influenced by the time in which we came to being as a band – we certainly were. But any musician who arose in the 80s were children of the 60s and 70s, so that was really our influence. In that sense, I grew up listening to the great songwriters of the 60s and 70s, and they were traditional songwriters, by and large. And if they weren’t, they were incredibly inventive.

“Then you had this collision with the 80s, which was really the ascent of technology – the more widespread use of synths and drum machines and sequencers – and yet this old-school way of writing songs. That’s why that particular decade was unique, it was that interesting combination. That was probably why Turn Back The Clock sounds the way it does. It’s got a foot in previous decades and a foot in the decade in which it was released.”

Datchler admits that, in some ways, it’s more difficult for the 21st-Century incarnation of Johnny Hates Jazz than it was in the 80s.

“Although I thought when I was younger that I faced a mountain trying to get a record deal, it’s tougher now, because you’re struggling to be heard among a plethora of people who are just releasing anything.

“The positive thing is we have an identity as Johnny Hates Jazz, and it’s something I appreciate more as an older person. Whenever we do have a little bit of success, or some kind of appreciation, I do appreciate it a great deal more than in the past. In that sense, it is more enjoyable. I think we’ve got things more in measure. We’re learning, when things go well, to just say: ‘That’s magical’.”

- Read more: Top sophisti-pop albums

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.