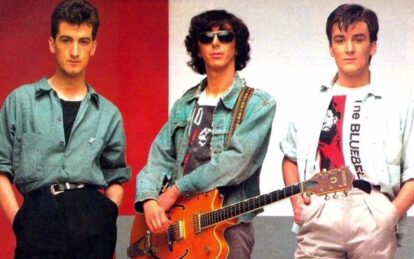

Photo by Bob Gruen

Generally a band determined to look forward, even Blondie can’t help revisiting their past when faced with a long-planned, gigantic boxset marking their imperial first phase. With Debbie Harry, Chris Stein and Clem Burke in unusually reflective mood, they reveal the differences between pop and punk, how they could have kept going longer – and rubbing shoulders with Orson Welles…

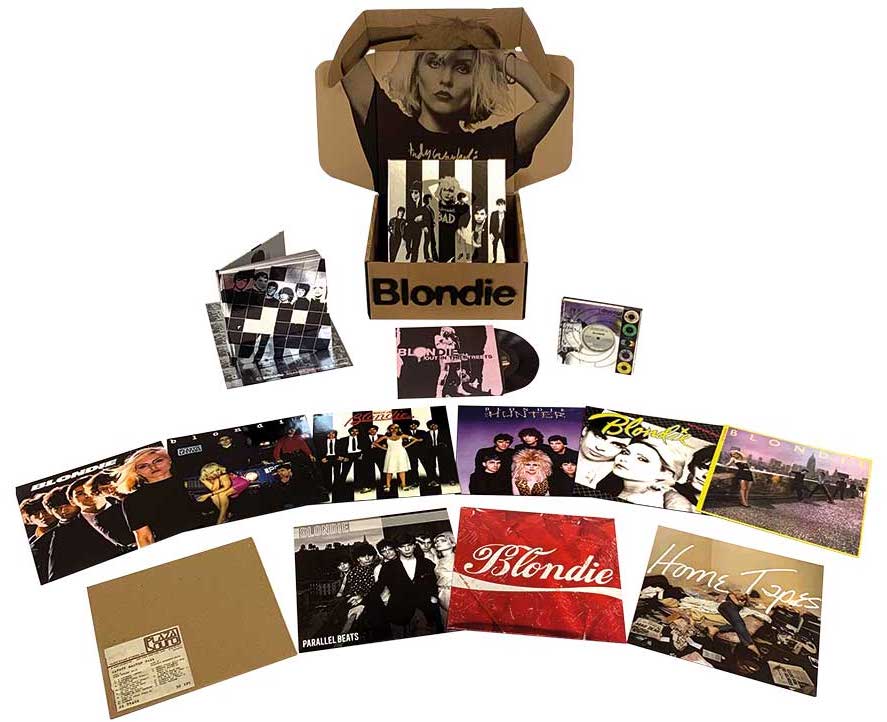

Initially scheduled for release four years ago, Blondie’s first major boxset, Against The Odds, is literally one of the biggest collections Classic Pop has ever encountered. Our postman hasn’t stopped scowling since having to lug it from the van.

The set comprises 10 vinyl albums, two singles and two hardback books, with even the cardboard mailing parcel unique: it’s got a monochrome vintage photo of Debbie Harry stamped on the inside.

No wonder even Blondie’s usually deadpan guitarist Chris Stein is animated discussing the venture. “It looks amazing,” he enthuses. “I didn’t realise just how grand that boxset was going to be as a physical reality.”

A pause, as Chris tries to think how to summarise the compendium of his band’s golden first phase. “It weighs 18 pounds,” the guitarist breathes, in the awed tones of a fisherman on his greatest catch. “It’s very impressive.”

However, Chris isn’t totally delirious when discussing the boxset compiling Blondie’s first eight years, when they went from trashy upstarts viewed as also-rans in New York’s thriving underground 70s scene to the most glamorous, sophisticated band of theirs and pretty much anyone else’s era, making a succession of stunning singles every bit as cool as their image.

The press release for Against The Odds states that the boxset’s 50+ extra tracks were mostly sourced from demo tapes Chris had kept in his barn in upstate New York. It’s that info which Stein disputes.

“I don’t know how the word ‘barn’ has got out there, I don’t have a barn: the tapes were in a garage next to my studio. In my eyes, a ‘barn’ is a much draughtier affair.”

It’s at this point that Debbie Harry joins proceedings. She’s missed the first two minutes of our conference call, because, well, she’s Debbie Harry.

She’s warm, inquisitive about people and laughs a lot, a delighted and uncontrolled burst as infectious as her vocals. But also: you’re talking to Actual Debbie Harry. Don’t mess this up, now.

Debbie doesn’t introduce herself, instead immediately out to make mischief with her eternal right-hand ally.

“Yeah, but what you’re talking about could be a barn,” Harry points out, to Stein’s frustration. “No it’s not!” he exclaims. “What I’ve got is sealed off and temperature controlled.”

Debbie responds: “Sure, but some of those modern barns are really well-designed, you know?” It’s at this point that Chris – friendly, jokey, but also with the imperious air of a man who knows full well he’s been one of the coolest people in New York for 45 years and counting – admits defeat.

“I guess so,” he mutters. “I just picture barns with grass, straw and cracks in the walls. My image of a ‘barn’ is different to yours.”

And that’s Classic Pop’s introduction to one of the great partnerships in pop: good-natured bickering about barns. It’s not all drug-fuelled mayhem and hanging out with Talking Heads.

Though, sure, that comes into play in their story, too. In the book about the band’s history inside the boxset, Debbie says the character of Blondie was clear from the start: if Blondie was falling from the top of the Empire State Building, she’d want to have fun on the way down. Does that still apply 48 years later?

“Yeah, sure!” she says, before another laugh whose sound suggests everything might be OK in life after all. “Having a sense of humour about who you are is the ideal outlook on life. It’s self-preservation at its highest. That and a certain sophistication have always been there in Blondie.”

Chris adds: “You have to see life as amusing, otherwise it just gets grim. I’m always amused, even as America slides into mediocre fascism. I’m hard-pressed to know who’s doing a better job of that, us or the UK. It’s ‘hold my beer,’ as they say.”

Despair at Western politics aside, Blondie can afford to laugh at themselves now. When they started, any self-mockery was more about gallows humour.

Before their pugnacious self-titled 1976 debut album, the group were more of a stepping stone to cult stardom elsewhere than valued for their own merits.

Second guitarist Ivan Král quickly left for Patti Smith’s band, then bassist Fred Smith departed to join Television.

It was new drummer Clem Burke who stopped Blondie falling apart.

Talking to Classic Pop the day after Grayson Perry hosts a ceremony granting Blondie a fellowship to London’s St Martin’s School Of Art, Clem, an affable, perennial optimist explains: “If you’re in a band, you need a vision to believe in.”

It’s easy to see why people would want to join any band of Clem’s. “As a drummer, I’d been looking for a David Bowie or a Jim Morrison as the frontperson in my band. When I met Debbie, I knew she was my Bowie, my Morrison.

“She was super-talented, obviously glamorous. I had no problem in seeing the magic that could be there in Blondie.”

Clem suggested his old schoolfriend Gary Valentine and pal Frank Infante as Blondie’s new bassist and guitarist respectively.

Soon after, looking for a pianist to further their retro sound to stand out from the punk crowd, Blondie instead met keyboardist Jimmy Destri, as Gary was friends with Jimmy’s sister.

- Read more: Blondie – the complete guide

“A lot of things happened by accident,” laughs Burke. “At the time, you think everything is going according to the pre-ordained vision of success that you have in your head when you’re 20. The New York scene was enigmatic, but also very insular.

“That whole scene consisted of maybe 100 people, about 85 of whom were in bands. But all of those bands were interesting, and we could see things in one another. We’d cover songs by Television or Ramones before they’d even been recorded.

“Crucially, we could make mistakes in public, finding our way at those early shows. Even at the time, I saw the CBGB’s club as our version of the Cavern where The Beatles started.”

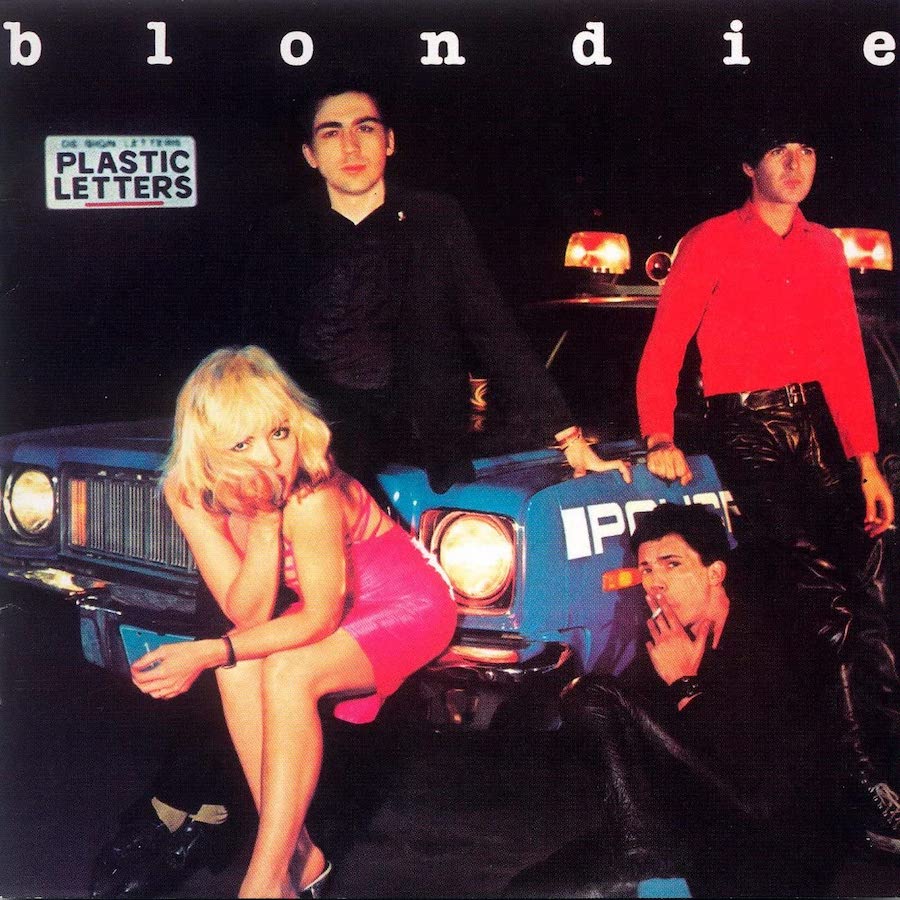

Second album Plastic Letters is where Blondie’s pop ethos starts falling into place. It’s largely as rough and ready as its predecessor, but it also contains the absurdly catchy Denis and (I’m Always Touched By Your) Presence, Dear.

Those first two albums were produced by Richard Gottehrer, previously a songwriter at the Brill Building alongside Carole King, where he penned hits including Hang On Sloopy and future Bow Wow Wow smash I Want Candy.

“Richard was more of a jazz producer than a pop guy,” states Harry. “He really liked finding a band’s live sound.” Stein agrees, adding: “We’d do four or five takes and Richard would choose the best one. He didn’t push us much beyond that. Those first two albums are semi-live.”

Burke points out: “Richard focused in on what he thought could be singles: X Offender, Denis. The idea was to have a hit, then thrash out the rest of the songs to fill out the album. Those first two records are great, but some of it is better produced than the rest.”

The contrast between the carefree Denis and the attitudinal punk of most of Plastic Letters established an unpredictability that has carried on throughout Blondie’s career.

To the public, it was thrilling that they couldn’t guess what their next single would sound like. To critics who needed to categorise a band, being too pop for punk and too punk for pop was more problematic.

“All those significations about punk, pop or reggae, they were always more relevant to their time period than the style of the music itself,” reasons Debbie.

“When it was happening, the punk scene embodied a lot of different styles and a lot of different types of music. It was only later that ‘punk’ came to represent a particular kind of music. What we were called was always down to whatever time period we were in, more than the music we made.”

- Read more: Top 20 Blondie songs

Another laugh. “We always seemed to be the exception to any scene’s particular rules.”

Chris joins in the laughter, noting: “Whether we cared what we were called depended on how much we cared about the media at any one time. We always called ourselves a pop band.”

Burke adds that Blondie thrives on sowing confusion: “Our musical palette is very broad. Besides, 50% of people think Blondie is Debbie. And in a way, she is Blondie, but it’s the band, too.

“There’s a lot of that type of confusion with us. One of our strongest redeeming values is that no-one knows what to make of us.”

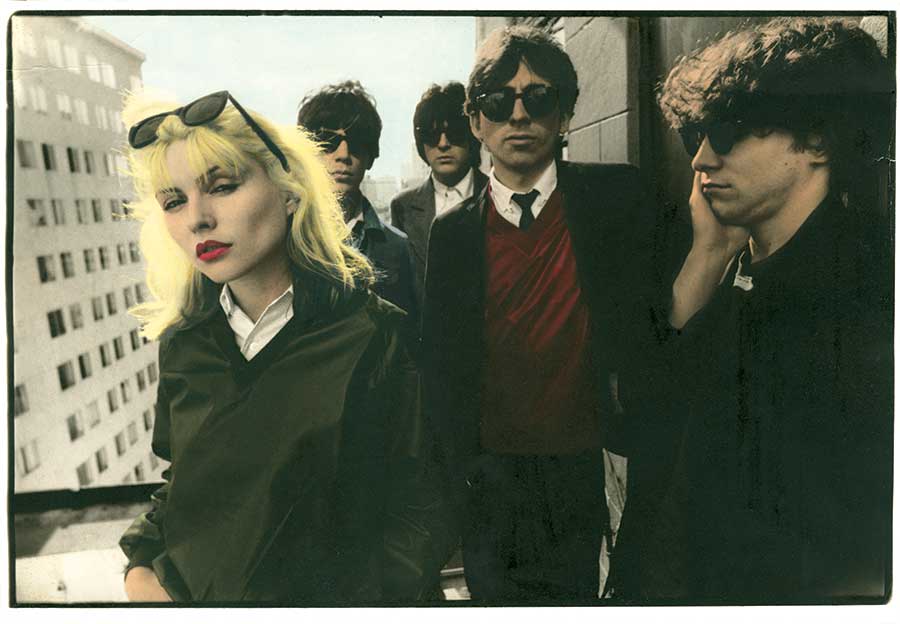

Photo by Martyn Goddard

Blondie’s then-manager Peter Leeds was a divisive figure, happy to heighten the perception that everyone in the band was disposable except Debbie. But Clem accepts Peter was also canny enough not to let Blondie be defined by scenes.

“We were asked to support the Sex Pistols on their Anarchy Tour,” the drummer reveals. “Our manager, probably very wisely, turned it down because he said the Pistols were too associated with punk rock.

“He had us shy away from that label as much as possible, telling me not to accept a Drummer Of The Year award from a punk magazine. But we were punk, in terms of being outside of society and not following the rules.”

The clearest move away from punk came with third album Parallel Lines, an all-time classic featuring Heart Of Glass and One Way Or Another and housed in photographer Edo Bertoglio’s iconic sleeve that embodied Blondie’s defiance.

The band’s songwriting had outgrown Richard Gottehrer. For a more streamlined approach, they turned to Mike Chapman who, together with Nicky Chinn, was responsible for defining 70s glam as producer for The Sweet, Mud and Suzi Quatro.

“We liked Tiger Feet as much as we liked The Velvet Underground,” notes Clem. “We were into bubblegum music, and the Ramones said The Bay City Rollers influenced Blitzkrieg Bop. But don’t forget, those big songs Mike produced that went to No.1 in the UK, none of them meant anything in the States.

“Nobody knew who The Sweet or Suzi Quatro were back home. It meant we were looking outside the box in working with Mike: we’d have a headstart in Europe, but the sound would take people by surprise in the States.”

- Read more: Debbie Harry on film

“Mike was great,” reflects Stein. “One of the key things I learned from him was how to repeat something and still keep it fresh. Knowing that repetition is worthwhile is a skill you need in pretty much every artform, like Stanley Kubrick directing 40 takes for a scene in a movie.”

That meticulous approach jarred with Debbie, who labelled the producer “a dictator,” but she acknowledges now that the discipline paid off.

“Mike occasionally drove me crazy, but that’s a pretty short trip,” she chuckles. “I had a hard time doing a lot of takes, but I learned a lot from Mike, too. I learned to listen more carefully, which is invaluable in acting as well, where listening is more important than your own portrayal.

“And Mike recognised that singing and playing an instrument need to be treated differently. An instrument won’t wear out or get tired, but a voice will. He wouldn’t make me sing something over and over for an hour straight, which he might make Chris or Clem do.

“So there was still a lot of spontaneity in my vocals, no matter what I might have said otherwise at the time.”

Blondie insist that, though Mike streamlined their sound, they weren’t out to turn themselves into a pop juggernaut. Stein explains: “The songwriting horizons have always been the same. The conglomerate of Blondie has always had the approach that anything goes. That’s been true from when we started up until now.”

Burke reasons: “We’ve always thought we were being experimental. There was a backlash against Heart Of Glass, because we were supposedly ‘going disco’, but we were just trying to see if we could merge Donna Summer with Kraftwerk.

“Sure, we thought Heart Of Glass was a great song, but we buried it. In the days when bands put the songs most likely to be a hit at the start of an album to impress a DJ dropping the needle on a record, we put Heart Of Glass as the 10th song on Parallel Lines.”

Follow-up album Eat To The Beat features the timeless Union City Blue, but even Mike Chapman wasn’t able to force as much of a cohesive record from his charges. In the boxset’s book, the producer says Blondie’s fourth LP was “chaotic,” stating drugs were beginning to infiltrate the band.

“Mike is kinda right,” considers Chris. “At the same time, everything was chaotic about Blondie. There was always tension and insanity, and that made for good records.”

Debbie adds: “Tension and chaos keeps people on their toes. It gives you drive, but there’s positives and negatives when you live your life like that. Musically, it worked out well for us, but there are so many things that influence a band which have nothing to do with music.”

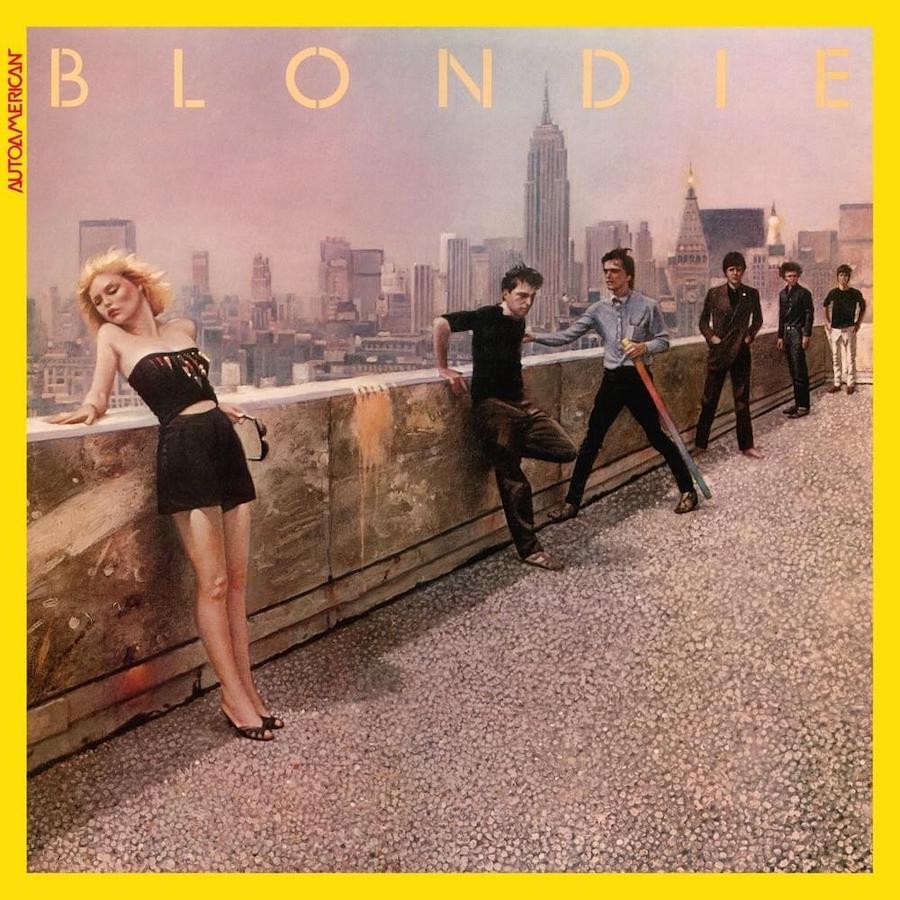

By fifth album Autoamerican, Blondie were seeing in a new decade with a change of approach. The quintessential New York band decamped to Hollywood, working at United Western studios, where Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley recorded, as well as The Beach Boys making Pet Sounds.

“Mike lived in L.A.,” explains Debbie. “After two albums where he’d come to New York, it was time to meet Mike halfway. Also, it meant we could socialise with a totally different crowd to our regular crew in New York.”

Chris continues Debbie’s theme, noting: “United Western had lobby rooms with glass doors, which were great for watching people walk by on the strip. If you got stuck with anything, you could relax by seeing all the crazy bullshit happening on the street outside.”

The studio was also good value for star spotting. A fan of the sitcom Three’s Company, Debbie was delighted to bump into its star, Suzanne Somers.

“I don’t know why Suzanne Somers was in a recording studio, but she brushed past me one day in the corridor,” recalls Harry. “I thought: ‘Oh wow, she looks good!’”

Chris less fondly remembers cheesy crooner Perry Como, growling: “Perry fucking Como was in there.”

Photo by Michael Zagaris

This is news to Debbie, who interrupts, asking: “Perry Como? Was he?” Chris responds: “Yeah, he was doing some fucking choir bullshit while we were trying to record The Tide Is High.”

If the generation gap between Some Enchanted Evening and The Tide Is High wasn’t enough of a headmelt, a further contrast was provided by another studio resident. United Western is where Orson Welles recorded voiceovers for his commercials for wine producers Paul Masson California.

“I tried to squeeze past Orson Welles in the studio hallway,” remembers Stein. “He was so gigantic by that point, that was hard to do. I don’t think we interacted with him beyond nodding.” Debbie interrupts, remembering her own moment with the director.

“No, that’s not right,” she tells Chris. “Don’t you remember, I had my little autograph book at that time? It was in the shape of a snubnose revolver. I pointed it at Orson Welles and told him (adopts stern voice): ‘Give me your autograph!’” Debbie got her signature.

As enjoyable as their starry encounters were, Blondie were poleaxed when their label, Chrysalis, declared Autoamerican didn’t have any hits.

This, let’s be clear, is an album containing The Tide Is High and Rapture. Record companies, eh?

“By that point, we’d stopped guessing what was going to be a hit,” laughs Clem. “I don’t think even our record company knew what to make of us. In the States, we’ve had three No.1 singles: Heart Of Glass, The Tide Is High and Rapture.

“That’s a dance song, a reggae song and, for want of a better term, a hip-hop song. You can’t get three more different songs. Innovation is probably our greatest strength, but at the time we thought we were just playing around.”

Nowhere was the playing around/innovation axis better explored than Rapture, the global smash credited with introducing hip-hop to the mainstream. Chris was especially excited by its potential: “We’d only heard a couple of songs on the radio, like Rapper’s Delight.

“Then we started seeing some of the live hip-hop shows. Being exposed to all that was such an eye-opener. It was just so great.”

- Read more: Making Madonna’s Like A Virgin

Debbie agrees, but adds a caveat: “I only did one vocal take for Rapture. That was fine for the melody, but I’d have preferred more time on the rap. What was new about Rapture is that we approached it like a normal piece of music, at a time when rap relied on beats and samples and didn’t have its own ‘songs’.”

It’s that frustration at not perfecting something which Harry notes of the boxset’s bonus material: “In those old demos, I hear bits and think: ‘Hey, that’s really good!’ I’d like to develop some of those parts. But you always want to revise things once you get a different perspective.

“The exciting aspect for me is that it goes alongside a particular era and state of mind. If I hear something that could be improved on? Well, that’s all shoulda, woulda, coulda, right? I mean, Rapture did pretty good anyway.”

Even someone as laidback about their past as Debbie admits the final album from Blondie Mk.1 was a missed opportunity. 1982’s The Hunter, which closes the boxset, was recorded after Debbie and Jimmy Destri made solo albums, while Chris went on to further his hip-hop adventures by curating the soundtrack to rap film Wild Style.

Coming back to the group, none of the six Blondies could work out what The Hunter should be.

“There was a lot of frustration within the band,” admits Chris. “There was a lot of drug abuse by then, all sorts of shit. But, all things considered, there are some great songs like English Boys on that record.”

Referring to the album’s none-more-1982 sleeve, Chris sighs: “The concept was to present the band as half-human, half-animal. But we didn’t get proper support and the cover just didn’t get done properly.

“If The Hunter had a better cover, it would have been a lot more successful.” Clem adds: “Our biggest mistake was taking too much time off after Autoamerican. We hadn’t got to the point we needed, even though we thought we had.”

It would be 17 years before Blondie returned, sharp as ever on 1999’s No Exit. There have been five albums from the new incarnation: a sixth will follow in spring.

“Debbie doesn’t like looking back,” notes Clem. “It’s so much better for Blondie that the boxset is out when we’ve just done a great UK arena tour and have finished the basic tracks for a new record. It’s got a few classic pop songs on, but it’s pretty eclectic. That’s what Blondie has always been about.”

Inevitably, it’s Debbie who has the final word.

“In Blondie’s historic way, we’re reaching into areas that are outside our norm. This new record? It isn’t straight-line pop.” Refusing to take the obvious route is about the only predictable aspect of Blondie’s career. Here’s to more classics from everyone’s favourite disco-rap-reggae-punk-pop heroes.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.