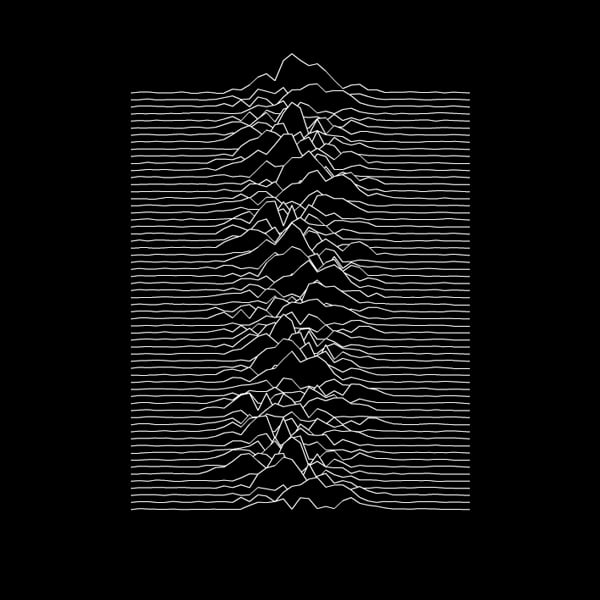

Joy Division Unknown Pleasures cover

In 2019, to mark the 40th anniversary of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, Peter Hook talked to Jonathan Wright about the “wonderful out-of-control excitement” of making one of the best debut albums of all time…

Over the course of their brief career, Joy Division made just a single appearance on national television. In September 1979, the band performed Transmission and She’s Lost Control on a BBC2 proto-yoof show, Something Else.

All of the elements that made Joy Division so compelling are in place: skittish drum patterns, the swapping of lead lines between guitar and bass, and a collective demeanour pitched somewhere between nerdy and belligerent.

And then there’s Ian Curtis, first twitching as he gets lost in the music before dancing like a man possessed, seemingly oblivious to his surroundings.

The contrast between the band’s first regional TV appearance, a performance of Shadowplay introduced by Tony Wilson for Granada Reports a year previously, is slight yet telling, a matter of more confidence, more experience, better clothes even.

The Joy Division of autumn 1978 are reaching, rich in promise, but by 1979 they’re the finished article, scarily good.

With 2019 marking the 40th anniversary of the release of Unknown Pleasures, it seems an apposite moment to ask, what alchemy made this possible?

“The thing is, probably the worst person you could talk to about it is me because for us it was such a struggle,” laughs bassist Peter Hook, speaking down the line from Portugal, where he’s playing dates with his band, The Light.

“It was a struggle to get on Something Else at that time. It was a struggle to survive as a group. It was a struggle to get every gig. There was nothing about it that was easy.”

In part, this was because Joy Division were helping to invent a new way of doing things, out of necessity as much as anything else.

- Read more: Peter Hook interview

Having formed in 1976, Joy Division, initially named The Stiff Kittens – likely at the suggestion of Buzzcocks manager Richard Boon – and then Warsaw, had already recorded a latterly much-bootlegged album for RCA offshoot Grapevine Records in May 1978.

They hated the results and, with the help of new manager Rob Gretton, freed themselves from the contract.

Instead of going to another major, Joy Division opted to go the independent route, recording for Tony Wilson’s nascent Factory Records, a label financed by an inheritance that Wilson received when his mother died.

Today, Joy Division’s decision doesn’t seem surprising, but it has to be seen in the context of the times, when there was near-incredulity at Stiff Little Fingers’ debut for Rough Trade, Inflammable Material, crashing the Top 20 album chart in early 1979.

This gave Joy Division autonomy, albeit with an accompanying financial downside. “They had no money to support us,” says Hook, “everything was self-financed.”

But what Factory did offer was the assistance of a collection of maverick talents, including producer Martin Hannett, who first worked with Joy Division on the band’s tracks for the A Factory Sample EP.

In April 1979, Joy Division and Hannett recorded at Strawberry Studios in Stockport, co-owned by Eric Stewart and Graham Gouldman of 10cc.

It was, says Hook, “a completely alien environment”, but there was “a wonderful being-out-of-control excitement” about working in a professional studio.

“It even felt more special because you were sneaking in at eight at night, working until eight in the morning, there was a real edge to what you were doing,” he remembers.

ESCAPE TO THE CENTRE

The Joy Division of this period were already a fearsome live outfit, a band forged in the crucible of punk. Salford school friends Hook and guitarist Bernard Sumner had, after all, been inspired to form Joy Division by attending the Sex Pistols’ legendary first gig, at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall, on 4 June 1976.

Ian Curtis attended the Pistols’ second gig at the same venue, on 20 July. Both shows were arranged by Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley of Buzzcocks. The Sex Pistols and The Clash, says Hook, were his heroes.

“We wanted to be a balls-out punk group, striding round, wall-of-sound type of thing,” he says. “And Martin recognised the delicacy and the depth in our songs, and told us in no uncertain terms that we were wrong, this was the way to do it, as we didn’t know our arse from our elbow.

“Because we’d never done it before. Luckily, he had the foresight to recognise what Joy Division was about, because we didn’t.”

The importance of Hannett, who “ruled by chaos and fear” and “certainly wasn’t a nice teacher”, to Joy Division’s sound is crystal clear.

The icy sheen he gave to the drums of Stephen Morris, for example, with the snap of the snare emphasised, changed how records sounded forever, yet it’s important to realise that Hannett was working with a band that had already begun to define themselves.

- Read more: Inside Power, Corruption & Lies

To return to that Granada Reports performance, the elements are in place, in particular the material, honed through rehearsal and gigging.

“He didn’t change the songs,” says Hook, who was initially very unhappy with how the album sounded. “What he did was he changed your perception of how they sounded.”

Yet in one sense, Unknown Pleasures was a classic punk album, in that it was about escape. Joy Division, Hook points out, were a Salford band, which has always been “Manchester’s poorer cousin”. Which in the late 1970s meant it was grim.

“We were just growing into adulthood, scared to death, the nihilism of punk was the perfect antidote to the confusion we felt,” he says.

Yet rather than rage at the bleakness of their surroundings, captured in so many chilly images of the band, Unknown Pleasures turned this energy inwards.

“It was very indirect,” says Hook. “A lot of punk albums were very direct weren’t they? Yet Joy Division were creating a landscape. We enabled you to dream about what you’d do when you’d got out.

“Punk was like someone screaming at you to get off a bus: ‘Get off, you fucking bastard!’ And ours was, ‘We’re going to get off this bus and we’re going to go somewhere wonderful.’

- Read more: New Order – album by album

“That’s to me what the equivalent of punk against Joy Division was. You were going to go somewhere, but you were going to go somewhere much dreamier.”

This image of Joy Division as opening up possibilities is one that’s worth pausing upon.

Because of the suicide of Ian Curtis, the band’s story is often told as a tragedy, to the extent it’s difficult not to see a track such as She’s Lost Control, about a young and severely epileptic woman Curtis encountered when he worked at Macclesfield occupational rehabilitation centre, as somehow foreshadowing what would happen.

And yet Joy Division’s story is also about optimism, about the special magic of four disparate characters where the sum was far greater than the constituent parts.

Yes, Ian Curtis was a troubled autodidact inspired by Iggy Pop and Berlin-era Bowie, and the writings of Ballard, Burroughs and Dostoevsky.

But he was also the man who, before the band signed to Factory, demanded Tony Wilson put Joy Division on TV.

“He was driven, he was so ambitious and he wouldn’t let anybody get in his way,” says Hook. “Storming up to Tony Wilson and calling him a c*nt. ‘You fucking should have us on your fucking programme, you wanker, because we are the fucking best thing since sliced bread!’”

Curtis the introvert, encouraged to express his “naughty, laddie side” by Hook and Sumner, often acted as Joy Division’s cheerleader.

“Ian Curtis was a great one for saying to you, ‘We are fantastic, the world will catch up, and all we’ve got to do is just buckle down, stick with it and we’ll be fine’,” says Hook.

“Because when you can’t get a gig as a group, it’s the most disheartening feeling in the world, you just want to give up. You’re working so hard under such awful conditions.

“Unknown Pleasures was written in something like minus five degrees in a warehouse where your hands were blue with the cold. It was a real struggle to write under those circumstances, but we did it.”

INTO THE WORLD

On 15 June 1979, Unknown Pleasures was released. Its cover featured an image of radio waves from the pulsar CP 1919 that Bernard Sumner had found in The Cambridge Encyclopaedia Of Astronomy.

Designer Peter Saville reversed the image from black-on-white to white-on-black, while initial sleeves were printed on textured card. It not only sounded special, it looked special. This was something new.

- Read more: The story of Factory Records

More prosaically, Factory pressed up 10,000 copies, which Hook and Rob Gretton personally picked up from the pressing plant in London and took back to Manchester.

The records had to be lugged up three flights of stairs to the Palatine Road flat of Factory director Alan Erasmus while, according to Hook’s autobiography, Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division, actor Margi Clarke noisily had sex with his flatmate in the bedroom.

On 20 July 1979, Joy Division made their second television performance, again on Granada, performing She’s Lost Control on What’s On.

Later that month, the band recorded Transmission at Strawberry, which would be released in October. In September, the band performed at the Futurama Festival in Leeds, an event that also featured the post-punk likes of PiL, OMD, Echo & The Bunnymen and The Fall.

- Read more: The Lowdown – New Order

By the end of the year, Joy Division had also recorded Dead Souls, Atmosphere and a John Peel session that featured Love Will Tear Us Apart and tracks from Closer, songs that showed them moving further still from their punk roots.

Then there was the October 1979 tour with Buzzcocks, mentors that Joy Division had in truth begun to eclipse. Throughout, this was a band operating on a shoestring.

“The Buzzcocks were playing to big audiences, so instead of these horrible toilets that you normally got changed in, you were actually in a modicum of comfort,” says Hook.

“I do remember being very hungry because we were only on £1.50 a day and, the Buzzcocks, they actually employed a minder to keep us out of their dressing room because we were so hungry; we were eating the whole fucking place, tablecloth and all.”

Hook laughs as he tells this anecdote, as he does often while he talks, a reflection perhaps that he’s comfortable in his own skin after quitting booze and drugs several years back.

Nevertheless, there’s inevitably also regret. On 23 January 1979, Curtis had been diagnosed with epilepsy and, even as Joy Division became more successful, there was a sense that Ian shouldn’t be performing in a band at all, with gigs – played with austere lighting so as not to trigger Curtis’ condition, sometimes interrupted by fits.

- Read more: Remembering Manchester’s Haçienda

“He wanted you to be great and he wanted you to have a great time, much more so than himself,” says Hook. “He was not selfish at all and that led to his undoing because his lack of selfishness, his lack of interest in looking after himself, because he was always about making everyone else happy, led to his demise.

“We all know now that if you don’t look after yourself, you’re not going to be able to look after anybody else.”

But they were so young. “We were really young, stupid, ill-educated, especially with regards to epilepsy,” says Hook.

“It was terrible, but there were older people there. We sort of blame ourselves. I still blame myself in many ways for his suicide, but you have to remember that there were doctors, specialists, parents, loads of people, so many people around Ian, and they were unable to help him either. It’s about responsibility, isn’t it?”

Things were moving fast. Too fast as it turned out. Within a few months, Curtis, both his personal and professional lives in turmoil, would take his own life. The music, though, endures.

“Really, we had it all and yet we had nothing,” says Hook. “We had the talent, we had the songs, we had the image, we were going to change the world.

“None of us knew that we had everything we needed in our arsenal and yet as people, as a group, we had absolutely nothing, we had no material wealth, we certainly had no audience wealth. It was actually quite a wonderfully naïve, innocent period.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.