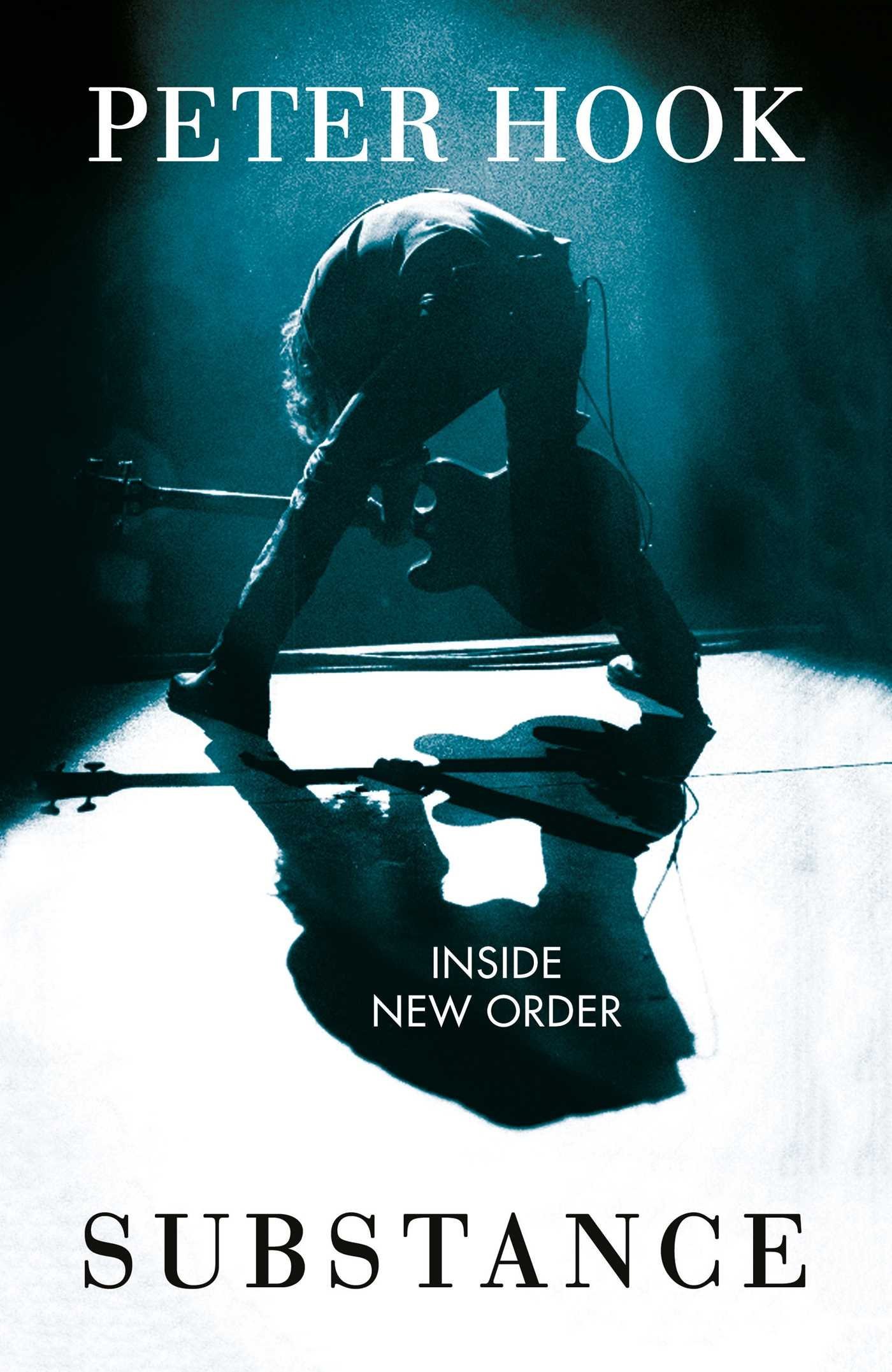

After the tragic death of Ian Curtis, the surviving members of Joy Division, including Peter Hook could have faded into obscurity – instead, 1981 saw them reborn as New Order, masters of alternative synth-pop. “We owned those 10 years,” Hooky tells Classic Pop

The suicide of Ian Curtis in May 1980 would have finished most bands. Yet, just 16 months later, Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris were releasing their debut album Movement as New Order, with Morris’ girlfriend Gillian Gilbert joining on keyboards.

Although he’s one of life’s great anecdotalists, a born comedian who just happens to be a brilliant bassist, even Peter Hook pauses when the speed of New Order’s achievement is put to him.

“We didn’t think about what had happened to Ian, or what was happening to us as people,” he considers. “Writing music had never been a problem for us, so we threw ourselves into that. It was the easiest way to find any familiarity. It wasn’t that we were thinking about what music we should do next, it was about doing what we always did.

“Before Ian disappeared, we’d always hang out at our practice place with our manager, Rob Gretton, and make music, and then we’d go to the pub together. So that’s what we did, and there was a lot of strength in that familiarity. There was a big hole doing it without Ian, of course there was. But the strength in that togetherness is what got us through it all.”

Before Sumner added being the frontman to his guitar duties and the band’s name was changed, the trio briefly considered carrying on as Joy Division. Kevin Hewick, a folk-tinged punk whose tremulous voice shared an outsider’s quality with Curtis, recorded a session as Joy Division’s frontman, which resurfaced in 2020 on Les Disques Du Crepescule’s compilation From Brussels With Love.

“I’m still friends with Kevin, who’s a lovely man,” enthuses Hooky of the singer, who still plays live and helps young musicians in Leicester. “Kevin is too nice to have been Joy Division’s replacement singer. We’d have eaten him alive.”

Although it felt natural to carry on writing what quickly became Movement, the uncertainty of what to do next was often overwhelming. “At the start of 1980, we were cocky, confident and almost arrogant,” Hooky admits. “Joy Division were so good that, when we looked around at our competition, we were laughing.

“Of course, when Ian died, we went down the snake and ended up at the bottom as New Order. We had a different attitude, a little more humbled. We didn’t have a singer, so we didn’t have anything in our armoury. It was a bleak time.”

Even after Sumner emerged as the new singer, the uncertainty remained. “New Order never felt quite right, as we were always Joy Division without Ian Curtis,” reasons Hooky. “With Ian, it was always the four of us writing together. As soon as Ian wasn’t there, it was obviously 25% harder. But you weren’t even 75% as efficient, because now you were doing two jobs – trying to focus on singing, as well as playing bass. It was such a weird, weird period as a musician.

Read more: Making New Order’s Technique

Read more: New Order – album by album

“I have wondered how we would have got on if we’d carried on as me, Bernard and Steve and just got another singer in. Simon Topping from A Certain Ratio was the other name on our wishlist with Kevin. But the gravity and expectation of replacing Ian Curtis, if we’d carried on as Joy Division, would have killed anyone.

“And we were good at making things more difficult for ourselves. When I started playing Joy Division’s music in The Light, filling Ian’s shoes was terrifying. It was a huge job, and it taught me a lot as a musician. It’s meant I’ve had two bites of the cherry, and it’s given me even more of an appreciation for Joy Division and the fans. I’m not a true vocalist, but singing those songs has taught me a lot vocally.”

The fact New Order were able to reinvent themselves so wonderfully was, at least initially, down to one simple reason. “The music stopped coming naturally without Ian,” Hooky explains. “As New Order, we had to work harder. And, it has to be said, we worked very hard.”

When did it feel natural to have Bernard as the singer? “2007,” jokes Hooky with a laugh. “I don’t think we had the luxury in New Order of feeling natural that often. We always felt we were running on a flat tyre and that, if we didn’t keep pumping air in, we’d soon be in trouble.”

Of course, given Hooky and New Order’s acrimonious split when the rest of the band reformed without him in 2011, Hooky’s explanation for their toil without Curtis could be seen as dismissive of their achievements. Hooky acknowledges that talking about New Order is difficult: “I’m jaundiced about it, because of what happened in 2011.” But the bassist is reasoned when talking about their times together and open about his bandmates’ musical prowess, despite the fallout.

He’s also begun appreciating their success afresh since auctioning some of his band memorabilia in February. “I’d approached going through those items with a heavy heart,” he recalls. “Then, once I started to look through it, I realised what a fantastic time we had, at least up until World In Motion. It was a reminder that it wasn’t always about clutching solicitors’ letters week after week, so the auction gave me back a bit of joie de vivre about New Order. From where we started, what New Order achieved was an incredible feat of rising from the ashes.”

Among the items up for auction were the earliest demos of Movement, recorded after the band’s first tour in September 1980 in America. “Because we’d been busy hammering away, we had a load of instrumentals written before America,” says Hooky. “We carried on when we got back and the whole of Movement was written before Gillian even joined. I’d got acoustic demos of the whole album in the auction.”

Read our feature on the making of Technique

Read more: The Lowdown – New Order

The biggest concern was recording Sumner’s vocals for the first time, which happened at their rehearsal studio, Pinky’s, in Salford. “My God, we were terrified,” is Hooky’s succinct summary.

As well as realising their guitarist was a capable vocalist and an almost uniquely enigmatic lyricist, the other major change from Joy Division to New Order was the introduction of synthesizers, with Gillian Gilbert soon graduating from Sumner’s studio apprentice to one of the key figures in synth-pop history.

“Synth-pop was an interesting movement, because it was very middle-class,” ponders Hooky. “The keyboards cost thousands of pounds, even in 1980, so you needed to be financially supported to own one. We weren’t like Heaven 17, whose parents were all teachers. We could only afford anything by default. It was interesting, because New Order were a post-punk band funded by a punk band’s money.”

Joy Division had gone full-time shortly before Curtis died. While New Order were launching themselves, they were so skint that a friend of Hooky’s got him a shift working as a roadie for Soft Cell at an early gig at Salford club Maxwell Hall.

“Soft Cell were excellent, and I’ve carried on being a fan of Dave Ball’s from his time in The Grid,” praises Hooky. “After I’d finished bringing their gear in, that show was where I saw goths for the first time. That was a revelation, as they looked like punks dressed up.”

That Soft Cell show was the reversal of another roadie encounter, when Joy Division had been lent a helping hand by a fan at a Sheffield gig, as Hooky remembers: “This guy in a greatcoat said to me: ‘Hello, my name’s Phil, can I give you a hand with your gear?’ I said ‘Yeah, very nice of you.’

“The trouble was, Phil had a long fringe covering half his face, and it kept getting in the way when he was humping our gear in. Still, it’s nice that Phil Oakey was such a big Joy Division fan, and we always felt an affinity with The Human League. Joy Division had toured with Rezillos, whose lovely guitarist Jo Callis joined The Human League after they split.”

Hooky is more of a fan of debut Human League album Reproduction than Dare, explaining he prefers more leftfield synth artists such as Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle.

“Cabaret Voltaire’s writing and forward-thinking nature was extremely impressive,” notes Hooky. “We met them early on, as they were on the Factory Records sampler. Once we began using synths, Bernard especially took a lot of inspiration from them and they were easy people to be with. Cabaret Voltaire were what Factory were built for: a DIY band in control of their own destiny.”

Read more: Top 40 synth-pop songs

Read more: Making Talk Talk’s The Colour Of Spring

Although they preferred “the more unusual groups to pop groups”, New Order enjoyed partying with their peers. “Me and Barney were the primary ones for clubbing whenever we were in London,” he states. “You’d see us, Soft Cell and Siouxsie and the Banshees together at Blitz, The Limelight and this great after-hours club in Notting Hill, The Cat Club, that didn’t have a licence.

“Our arrogance meant we had a certain seriousness as to who we deemed worthy of hanging out with, but if we’d bumped into Bucks Fizz I’m sure we’d have had a high old time with them too.”

The Haçienda proved another source of inspiration, even though Hooky admits he was initially there so often because he got free food and drink while waiting for New Order to earn any money.

“As soon as The Haçienda started putting gigs on, it felt like we were part of something bigger,” explains Hooky. “We were introduced to a different kind of music, through the DJs there as well as the bands.”

Thanks largely to Martin Hannett’s production, Movement, reissued as a deluxe edition in 2019, was more of a continuation of Joy Division’s sound than subsequent New Order albums. But it was still a marker in how New Order refused to be defeated by tragedy.

As an upbeat Hooky concludes: “We went from playing to 200 people in Brighton to 33,000 people in Toronto in the space of a decade. Maybe finishing after World In Motion in 1990 would have been the perfect place to end New Order, because we owned those 10 years.”

Read more: Making Dexys’ Searching For The Young Soul Rebels

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.