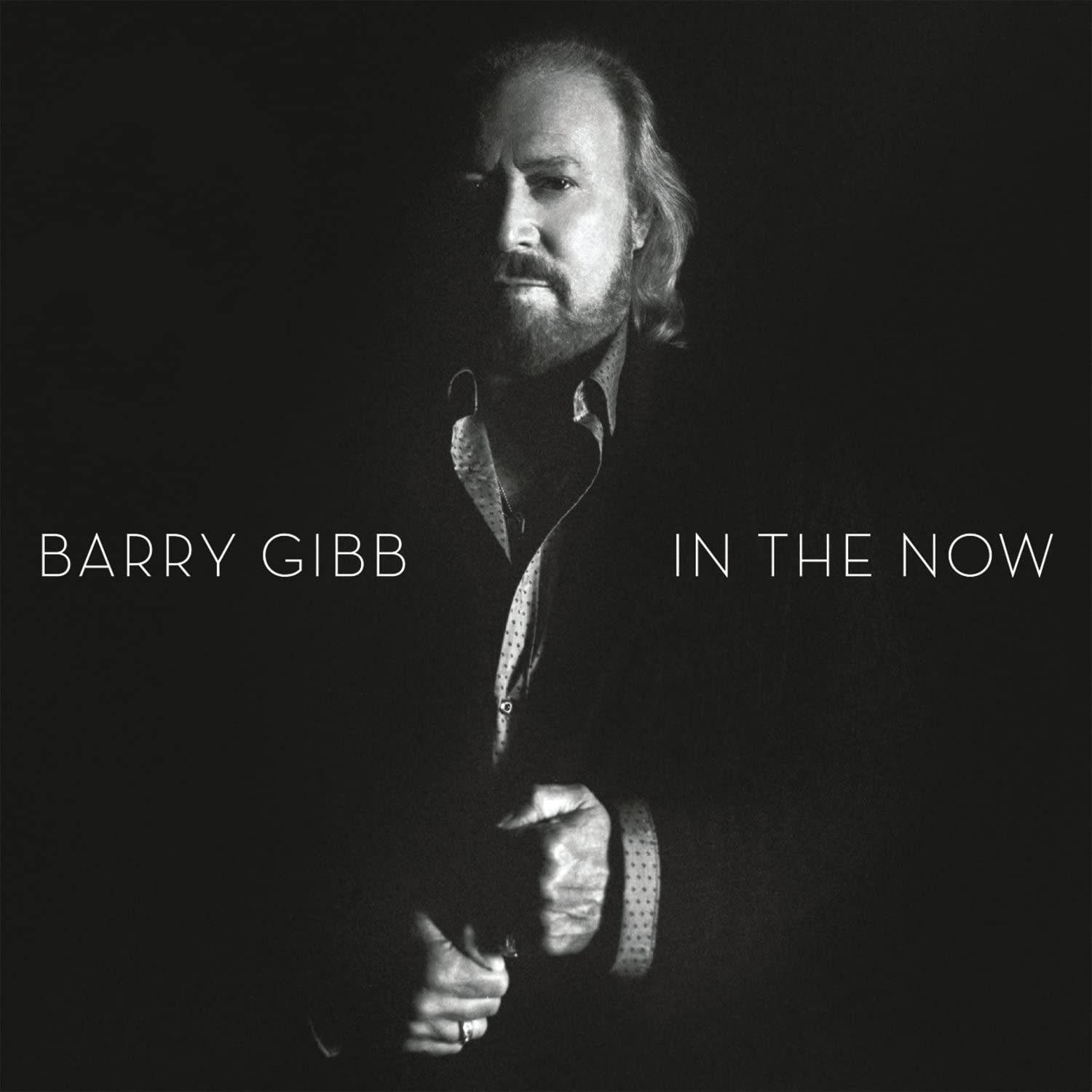

Barry Gibb of The Bee Gees

In 2016, Barry Gibb of The Bee Gees released his first solo album in 30 years. That year, at his favourite curry house, he sat down with Rudy Bolly…

One of the most recognisable voices in pop has been silent far too long. After the death of his brother Maurice in 2003, Barry Gibb called time on the Bee Gees for the first time. Then, in 2012, Robin Gibb passed away following a brave battle with cancer.

Having come to terms with loss, Barry has rekindled his passion for music via a new solo album, In The Now. “I no longer think of past, present or future,” he says. “In The Now represents my complete denial of time.”

With a euphoric Glastonbury Festival cameo still fresh in the memory, now is definitely the time for Barry Gibb again.

Born on the Isle Of Man, raised in Manchester and discovered in Australia, these days Miami is home to Barry Gibb. During a rare UK visit, the Transatlantic icon invited Classic Pop to his favourite Indian restaurant.

Perusing the menu in anticipation, Saturday Night Keema, To Love Some Balti and a glut of dodgy curry puns spring to mind until Barry informs us the kitchen is closed – “but come back, they do the best.”

It’s been 15 years since This Is Where I Came In – the songwriter’s last album of original material with the Bee Gees. In The Now also happens to be his first solo effort in over 30 years, yet the creative process was just like being back in a band.

“It took me a year to do and I co-wrote it all with my sons, Steven and Ashley,” he enthuses. “So the same circumstances seemed to prevail. It wasn’t about brothers but about sons this time.

“And a very similar process – they tell me if there’s something they aren’t happy about and we were like that as brothers, too; that’s the team thing.”

Incredibly, it’s only Barry’s second solo effort in a long and auspicious career. A little uncomfortably, he explains: “I don’t think I’ve ever put out a serious solo album. I did try one called Now Voyager way back.

“But my brothers didn’t want me to, there was a lot of discouragement to go solo because of the Bee Gees. That’s what you deal with if you are brothers, being in the family bad books, so I didn’t really try.

“Although truthfully, Andy [Gibb] included, we all wanted to be a solo artists, no matter what… and I think that probably exists in all groups.”

The sense of duty weighed heavy on the eldest brother and the lack of solo opportunity does seem a little unfair, especially considering that Robin issued many solo records.

Barry nods: “Yes, he released about four or five and had some success, but his comment is always the same – it’s not that much fun if you are on your own.

“We grew up together, and although we have a desire to be individually recognised, it’s not that enjoyable if you are not actually together.

“We were 45 years as a group so stepping away from that has never been easy and even today it wouldn’t be any easier if we were all together.

“People think of the Bee Gees no matter who it is – me, Maurice, Robin or Andy; for me it’s the Brothers Gibb, always has been.”

- Read more: The complete guide to The Bee Gees

That contradiction of seeking solo recognition while maintaining the group tugged at Barry his entire career. He’s one of the most prolific songwriters of his generation, which leads us to wonder… what has he been doing these past 15 years?

“I fell in love with bluegrass music, right after Robin passed,” he explains. “That led me to Nashville, buying the house that Johnny Cash lived in, which consequently burnt down.

“So I didn’t get to complete that project, but I wanted to investigate it all. I started following my own tastes, I didn’t have to worry about what somebody else wanted me to do. I had no brothers telling me, ‘you can’t do that’ or ‘you gotta be mainstream’, so I wandered off the path.”

As Islands In The Stream will attest, country has always been in Gibb’s music. However, there’s barely a patch of gingham to be found on In The Now.

From the manic riffery of Blowing A Fuse to the hymn-like End Of The Rainbow, diverse is most certainly the word. Star Crossed Lovers, drenched in the nostalgia of his Fifties childhood, is a personal favourite.

“That’s my Carole King song, it’s for my wife Linda, we were star-crossed.

In 1967, if you were a pop artist signed to a label, you weren’t allowed to have a girlfriend. I think it still happens today, because it may turn kids off. So she always had to hide or stay at home.”

The sense of musical juvenilia mirrors some of the reflective mood that drives David Bowie’s 2013 comeback album, The Next Day, and perhaps it’s no great surprise considering Bowie and Gibb were born just six months apart and reared on the same diet of skiffle, rock’n’roll and The Beatles.

Now 70 years old, Barry muses: “I never met Bowie. I think he was very smart and avoided being associated with anybody that didn’t relate to his image.

“But we both come from the same era. Songs like Amy In Colour go back to that time – it’s my McCartney song, about that one-night stand who you never saw again.”

Barry also tackles themes of violence, religion and, in The Grand Illusion, an entirely new way of existing. “Time and loss equals a new way of thinking for me: death is just as natural as life,” he offers. “If you’ve lost all your brothers then you don’t look at death the same way.

“In fact, it’s perfectly fine with me. There’s no way we are going to hang around for more than a hundred years, so now I love the moment… and we should all stop moaning.”

Another highlight on the album is Home Truth Song, a piece which is already becoming a live favourite. “That’s all bluster and ambition,” nods Barry. “The lyrics go ‘I’ve been to heaven and hell and living underground’ – because I refuse to be chained down and stuck in a white suit with medallions.”

We have hit upon a rather raw nerve here – that of disco. In spite of the monumental success the late Seventies brought, it’s an era that continues to haunt him. Barry has seemed a little guarded up until this point in the interview, even suspicious.

Without any prompting on the subject he continues, “Even now, whenever I do any press, there is rarely a picture of me – it’s always the three of us in white or gold suits. I want to say, ‘Jesus, that was 40 years ago’.

“Look at how The Beatles used to dress, or Michael Jackson. Look at the giant shorts today, it’s all part of culture. We were that passing phase when everything was light-hearted, flared pants. Although personally I think Robin’s flares were bigger than mine…”

Barry’s imprint on popular culture should not be condensed into a pair of dodgy slacks; after all, the Gibb brothers are second only to Lennon & McCartney in terms of global songwriting success.

And yet, despite the near-unbelievable sales figures, Barry seems to remain uncertain of his own legacy, despite his appreciation of a more knowledgeable public whose love for his music transcends simply disco.

“I do feel the love now and it never ceases to confuse me,” he smiles, as if a weight’s been lifted. “I have no self-image, I don’t have great self-esteem, and the only way I can shout is to sing. So I was never able to understand any of it.

“If it worked then great, but in life more often than not things don’t work. We could put out a song and it was a monster and then another which would flop. So we never got firmly rooted in anything. We were always being pushed aside and then fighting our way back.”

If white suits were the visual caricature, then the Bee Gees sound was undoubtedly defined by Barry’s falsetto. Much-maligned over the years, that falsetto is pertinent again thanks to a wave of helium-pitched newcomers.

Barry agrees: “Sam Smith is a perfect example of the falsetto. But I’m just playing catch-up with Prince. The amount of falsetto he was using was outrageous. I mean, I got slapped on the hand, but he used to get away with it. I still doing enjoy it.”

The hateful ‘disco sucks’ campaign at the end of the Seventies curtailed an incredible chart run for the Bee Gees, so they switched attention to songwriting.

“When we did Islands In The Stream it was our way of getting other people to hear our songs. Because if we sang it, it wouldn’t have got on the radio, and I wanted the songs to succeed no matter who was singing them.

“Chain Reaction [Diana Ross] is another example, having other artists become your instruments. My brothers would say ‘we should be the ones doing Heartbreaker’, but I knew they wouldn’t get on the radio. ‘Let’s be songwriters and prove that point’.”

- Read more: The story of disco

Fear of failure seems to have driven Barry Gibb onwards throughout his career. “I thought it was all over for us in 1970 – the average group used to have a five-year span,” he agrees. “But I always seem to have a surge towards the end of each decade.

“1967 was when we were signed to [manager] Robert Stigwood. 1977 was the disco thing and ‘87 was the period for You Win Again. We blossomed towards the end of decades, then we got kicked in the pants again.”

He needn’t brace himself for another blow, for In The Now is a defiant, confident collection. And as the album reaches its finale it takes on a more mournful vibe.

“Shadows is my Roy Orbison song, the greatest songwriter – and the shadows is looking through his eyes.

“But I suppose it’s also me seeing my brothers when they are not there. Even on stage I can see them, I can smell their breath around the microphone, because we were so used to all singing around one mic. I could tell, ‘Oh, Maurice has had a drink’.”

That sense of loss continues on Diamonds – a moving account of Robin’s funeral. “I didn’t cry on that day. It was cold, almost black and white like a movie – the perfect funeral day. That song is from the heart – from the curse to the legacy, that’s my reflection on us through Robin.”

The theme carries over into End Of The Rainbow, where Barry almost sounds like Robin. “I sang a verse of it to Robin when he was in a coma. It’s my comment on time, increments on motion that keep us going. I don’t believe in it anymore.”

In The Now is worthy of Barry’s incredible back catalogue – a catalogue he owns himself. “We had to battle like hell to get it back, I basically went to war.”

Just as well, when you consider how many artists have covered his music. “Even Johnny Mathis and Andy Williams have sung our songs. Stayin’ Alive still gets a lot of requests, usually for an animated movie… and that’s great because kids get to discover it, too.”

No longer just a wedding disco staple, Stayin’ Alive enjoyed a revival thanks to the British Heart Foundation (and Vinnie Jones) using it for performing CPR. Amazed, Barry says: “It was a surprise, but that tempo is important.

“When I was in the studio recording it with Albhy and Karl [co-producers Albhy Galuten and Karl Richardson] it was 103 beats per minute.

“I left the room for a moment and when I came back I knew something didn’t feel as good. Karl said: ‘We moved it up one beat’. I told them to take it back because it wasn’t the same song.”

Besides the occasional top-notch curry, Barry has managed to avoid the clichés and excesses of a pop star lifestyle.

“20 years ago I bought a Lamborghini and saw myself in a shop window trying to get out of it. I took it back on the same week,” he laughs. “All I want these days is a touch of credibility, spiced with sake.”

All the same, another spin on the pop merry-go-round wouldn’t go a miss. “I’m not finished. If I get momentum with this album it will be wonderful because it wouldn’t always have been about the Seventies.

“If there’s a sunset then I’d like to go around the block one more time. I think there’s another chapter for me. I think I would’ve wanted my brothers to go on, and I hope they would feel the same way.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.