The story of disco music

By Classic Pop | May 10, 2024

Classic Pop looks back at the rise, fall and rebirth of a magical era in popular culture: The story of disco music…

During the summer of 1979 disco dominated the airwaves. Nightclub dancefloors around the world were awash with pretty young things, busting moves in the sharpest of satin suits and polyester. Everything that glittered was gold… and wrapped in lamé.

However, not everyone was digging this new boogie wonderland… on 12 July 1979 a baying mob, fired up by disgruntled radio DJ Steve Dahl, descended on Comiskey Park baseball stadium in Chicago.

Thousands of long-haired white males wearing ‘Disco Sucks’ t-shirts, stormed the pitch to frisbee records, by the likes of Gloria Gaynor, Donna Summer and the Village People, on to a growing funeral pyre.

As smoke billowed across the pitch, Dahl’s Disco Demolition Night had tapped into an ugly undercurrent of racism, sexism and homophobia… an uncontrollable outpouring of fear and loathing. What had disco done to provoke such ire?

Feel-Good Music

Wasn’t disco the most inoffensive, shamelessly feel-good music trend ever? Surely it was all sequins, platform shoes, mirror balls and medallions?

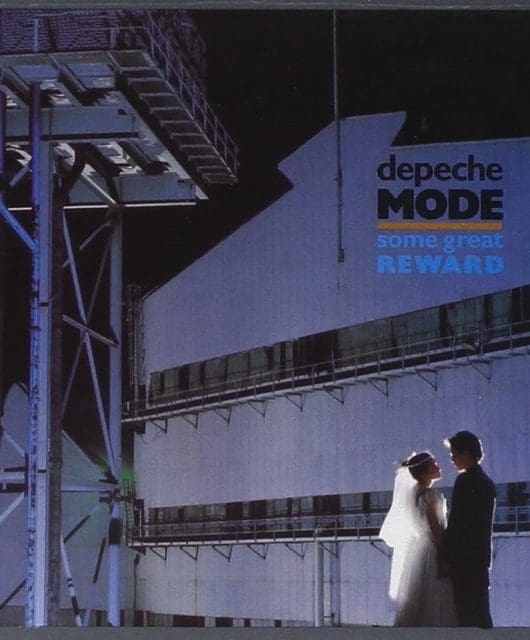

Wasn’t it lovable, with romantic numbers like Barry White’s You’re The First, My Last, My Everything; glittery dance numbers like Baccara’s Yes Sir, I Can Boogie; and irresistible singalongs like Ottawan’s D.I.S.C.O?

Celebrating the freedom of gay people, women, African-Americans and Latinos, disco had become a ubiquitous style loved by everyone from grandmas to their grandchildren; an advertising jingle used to sell everything from burgers to airlines; and a bandwagon jumped upon by everyone from Dolly Parton to the cast of Sesame Street.

But when it started, at the beginning of the 70s, it was an underground rebellion that grew alongside the civil rights movement, gay pride and women’s lib.

Its clubs were melting pots of black and white, gay and straight coming together for the first time in a hedonistic orgy of sex, drugs and dancing that the hippies of the 1960s could only dream about.

Dancing In The City

The story of disco began on Valentine’s Day 1970 at 647 Broadway in New York, where David Mancuso, an antique dealer and hi-fi enthusiast, hosted his first “Love Saves The Day” invitation-only dance party in the 2,000 square-foot loft where he lived. His bedroom was on a platform above the DJ booth.

Because The Loft, as it became known, didn’t serve alcohol or food, Mancuso didn’t need a cabaret licence for the weekly gatherings that became the hang-out of choice for a gay community that suddenly had a place where men could dance together without being hassled by the police in an era when you could get arrested for cross-dressing in public.

Other underground venues followed, using the same private house party business model, including the Gallery in Manhattan; the Flamingo at 599 Broadway; 12 West/The Riverclub, a huge amphitheatre in a former warehouse in Greenwich Village; and the Paradise Garage [also known as the ‘Gay-rage’] a former parking garage.

It wasn’t the first time patrons had danced to records instead of bands. The term discotheque originated in occupied France during World War II, where jazz clubs played records to sidestep a Nazi ban on live music.

But in New York in the early-70s, the clubs that became home to disco had a different culture to most nightclubs of the time, where people went primarily to drink and socialise, and dancing was something to take or leave.

Party Time

Mancuso used his knowledge of hi-fi to install an exceptional quality sound system in The Loft, and the clubs that followed all competed to outdo each other for sound and lighting to create an immersive experience for losing yourself in a world of music and dancing.

12 West, for example, had a state-of-the-art sound system designed by Graebar Productions that included two large corner loaded horns, four coffin speakers with mid-range arrays pointed at the dancefloor and a tweeter array above it.

The Infinity, a former envelope factory at 653 Broadway, was the first disco to be lit by neon, including a glowing penis on the black-painted wall of its block-long dancefloor.

It had so many mirrors and mirror balls reflecting each other that the place really did appear to stretch into infinity in every direction.

Later, when disco hit its peak in the late-70s, Xenon boasted a 16-channel sound system said to be the most expensive ever installed in a New York club, and a $100,000 ‘Mothership’ lighting rig that descended from the ceiling to just above the heads of the dancers, like the spaceship in the then recently released sci-fi flick Close Encounters Of The Third Kind.

Hey Mr DJ Put A Record On

As well as top notch sound, the emerging discotheque scene put DJs at the centre of club life. Jockeys like Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles didn’t just spin random records, they played them in a continuous swathe that took the audience on a journey.

They could also pick up on the mood of patrons, quickly switching to a track that would enhance what was happening on the dancefloor, in a kind of dance between dancer and DJ.

Club-goers also shaped the burgeoning disco scene. They dressed outrageously – many early discos were also drag clubs, or full of leather-clad ‘Leathermen’.

They came armed with tambourines and maracas, clapped and screamed. The best dancers were an unpaid part of the entertainment. The crowd would form a circle to applaud their splits and Russian leaps.

But as much as the disco scene was led by clubs, sound systems, DJs and a disenfranchised audience looking for a non-stop party to escape to, it needed a style of music to call its own.

The Disco Sound

The records played in the first house parties at The Loft ranged from the funk of James Brown to the Motown sound of The Temptations plus Latin jazz – there has always been music to dance to.

Gradually, though, a distinctive new style of disco music began to emerge, tailored to the scene that had arisen.

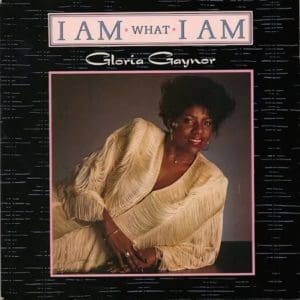

As former typist and hairdresser and later I Will Survive star Gloria Gaynor put it: “The discotheques that were popping up were going to need music specifically for dancing – so I decided that I was going to supply them.”

The classic disco sound can be defined by a prominent drum machine beat, funky bassline and itchy ‘chicken scratch’ rhythm, played tautly and close to the neck of an electric guitar.

Sumptuous string arrangements, generally high vocals and a jangle of hi-hat cymbals add a theatricality befitting the glittering environments and colourfully dressed patrons of the discos themselves, as do dramatic piano glissandi that tend to come sweeping out of nowhere.

Upbeat lyrics almost exclusively about love, empowerment or disco dancing complete a heady mix.

Soul Train

The roots of disco can be heard in the dance rhythms, punchy vocals and jingly hi-hat of Motown records in the 60s, and the smoother, string-laden Philadelphia Sound that began to challenge Detroit as the dominant force in soul music on the cusp of the 60s and 70s.

A lot of the inspiration for disco can be attributed to MFSB, the house band at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound Studios, which played on one of the first hits with a recognisable disco sound: Love Train by vocal harmony group The O’Jays.

MFSB stood for Mother Father Sister Brother, if you want the clean version, or Mother-Fucking Sons of Bitches if you want to know how hot they played.

Either way, Love Train had most of what you could want from a disco song, including its call for unity and inclusion – “People all over the world, join hands” – that was central to New York’s club ethos. It came out in 1972 and topped the US charts early the following year.

Rock The Boat

Other contenders for disco’s first big hit include Rock The Boat by the Hues Corporation and the orchestral instrumental Love’s Theme by Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra.

Arguably the record that really nailed down the sound of disco, though, was Rock Your Baby by George McCrae, which became a worldwide chart-topper in the summer of 1974.

The song was written by Harry Wayne Casey – the ‘KC’ from KC and the Sunshine Band – and his bandmate Richard Finch.

They cut the backing track as a Sunshine Band record at TK Records in Miami but Casey couldn’t manage the song’s high notes. McCrae happened to be on hand to stand in and went on to sell 11 million copies.

As well as McCrae’s sky-high “Ah-AHHs” and calls for his “Woooo-man” to “hold me in your arms and rock your baby,” the record was one of the first to feature a drum machine.

According to TK Records founder Henry Stone: “The Philly sound was a little bit on the sophisticated side. The Miami sound was more of a rhythm, groove, beat sound. Rock Your Baby was the first real disco record that launched the disco era.”

Get Down Tonight

KC and the Sunshine Band weren’t left on the sidelines by McCrae’s success. With Casey on vocals and keyboards, the group went on to enjoy a string of disco hits, including Get Down Tonight, (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty, and That’s The Way (I Like It).

As the white leader of a large band of predominantly black musicians and backing singers, Casey epitomised disco’s multiculturalism.

Gloria Gaynor, meanwhile, became the music’s first female diva with an album especially made for the dance clubs.

Produced by Jay Ellis, Meco Monardo, Tony Bongiovi and Harold Wheeler – collectively known as the Disco Corporation of America – the first side of her 1974 long-player Never Can Say Goodbye comprised just three songs, Honey Bee, the title track and Reach Out, I’ll Be There, run together into a continuous 19-minute swathe of music, characterised by a thumping beat, swirling strings and Gaynor’s soaring vocals.

It was an industry first and Gaynor, who had been singing in clubs since the mid-60s, was initially unsure about the extended format, observing that there were large stretches of music when she wasn’t singing. The producers told her: “You better learn to disco dance, then!”

You Sexy Things

The risk paid off when the disc took the dancefloors by storm and DJs played the whole 19 minutes. The extracted single, a cover of the Jackson 5’s Never Can Say Goodbye, was the first song to top the Disco Action chart when it was introduced by music trade paper Billboard to chronicle the emerging New York scene.

It also made the Top 10 of the US pop charts and took Gaynor around the world, hitting No.3 in Canada and No.2 in the UK.

Another long and ground-breaking recording was Donna Summer’s debut single, Love To Love You Baby.

Originally from Boston, Summer was an unknown in her home country and was working in Germany as a model when she teamed up with producers Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte to build Love To Love You Baby around a title that she had suggested.

Moroder sent a demo to Casablanca Records boss Neil Bogart in New York, who suggested an extended version for the discos. The result was a 16-minute sexual fiesta, with Summer delivering When Harry Met Sally-style orgasmic moans throughout.

Asked by hot-under-the-collar reporters whether she touched herself during the recording, Summer said: “Yes, well, actually I had my hand on my knee.”

Even more striking was Summer’s hypnotic I Feel Love on which Moroder and Bellotte replaced disco’s usual string arrangement with the pulsing electronic sound of a Moog synthesizer.

Sound Of The Future

When pioneering producer Brian Eno heard the track, he told David Bowie: “I have heard the sound of the future.”

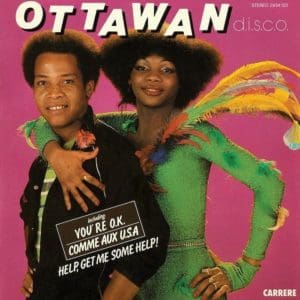

So inspiring was I Feel Love, it gave rise to the sub-genre Hi-NRG (high energy) and the futuristic synth-based Italo disco and space disco that flourished in European clubs in the 80s after disco’s demise in the States.

In the meantime, Europeans were putting their own spin on the glitter ball. British-based Jamaican Carl Douglas had one of the first big disco hits with Kung Fu Fighting – a one hit wonder, but what a hit, with 11 million records sold.

Another Jamaica-born Brit, Errol Brown, sang Hot Chocolate’s evergreen You Sexy Thing in 1975, while the male/female UK duo Marshall Hain had a one-off smash with the sultry Dancing In The City in 1978.

Swedish super troopers ABBA, meanwhile, scored their only US No.1 when they turned to disco with Dancing Queen.

The Mmainstream

Although disco was brightening charts around the world, the club scene itself remained fairly underground until the mid-70s. That all changed with the 1977 release of Saturday Night Fever which starred John Travolta as a hardware store worker by day who transforms into a disco-dancing god at night.

The straight white world portrayed in the film didn’t bear much resemblance to the disco scene up to that point, but it was just what the music needed to get a mainstream audience strutting its stuff on any dancefloor within reach.

That and a stunning soundtrack dominated by the Bee Gees. The English brothers Barry, Andy and Maurice Gibb had been making music since the late-50s as a skiffle band called Rattlesnake. As the Bee Gees, they first hit the big time in the mid-to-late-60s with ballads such as Words.

By 1974, however, changing tastes had reduced them to a cabaret act at venues like the Batley Variety Club in Yorkshire. Relocating to Miami, they regained their mojo with the disco-style Jive Talkin’. Although the song took them back to No.1, it merely primed the pump for the music they unleashed on the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack.

I Like The Way You Move

Deploying Barry Gibb’s falsetto for the first time, Stayin’ Alive and Night Fever became instant disco classics. The Fever… soundtrack staked out the top of the charts around the globe for weeks on end (18 weeks in the UK and 24 in the US).

As disco went mainstream, Studio 54, a former television studio on New York’s 54th Street, became the place to be seen… if you could get in. Celebrities like Liza Minnelli, Frank Sinatra and Andy Warhol were waved in by the bouncers and Michael Jackson could be seen in a corner talking to Woody Allen.

Among the many turned away on New Year’s Eve 1977, were Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards, even though they were famous for a string of hits and had arranged to meet Grace Jones inside.

Mightily miffed, they headed to Nile’s apartment and wrote a song with the shouted hook, “Fuck off!” With a subtle edit to “Freak out!” it became one of their biggest hits, Le Freak.

Disco Demolition

If disco began the 70s as a hideout for an oppressed gay community, then it’s apt that the decade ended with gay culture going mainstream via the Village People.

The group’s moustachioed line-up of gay fantasy figures – a cowboy, cop, construction worker and leatherman – almost parodied the audience in the clubs where disco originated.

But their all-pervasive hits Y.M.C.A. and In The Navy had the straightest of straights singing along. Even the navy loved them.

Radio station after station across America switched from rock to disco, in the process fuelling a growing resentment against the endless party.

Steve Dahl, the 24-year-old DJ who led the ‘disco sucks’ campaign was one of the jocks who lost his job when his station made the switch.

“At that time, disco was the only thing that would get you on the radio,” said Maurice White, founder of Earth Wind and Fire, when the r’n’b group joined the fray with Boogie Wonderland.

Union City Blue

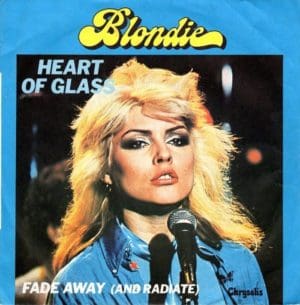

Deborah Harry was unapologetic when new wave rockers Blondie took the disco route with Heart Of Glass, but admitted: “Some of our friends from other rock bands were very put off that we did this disco song. They wanted us to be run out of town.”

As the disco bubble blew up to near-bursting point, the club scene looked like Rome before the fall: awash with cocaine and promiscuity.

AIDS had yet to be identified, but within a couple of years the free love party was going to end very badly and take many of the scene’s most colourful characters.

Something had to give, and when Dahl blew up the disco records at Comiskey Park in the summer of 1979, it really was as if the whole scene exploded and vanished in a single puff of smoke.

Million-selling stars disappeared from the airwaves almost overnight as the mood turned and US radio stations strove to woo back disco-ed out listeners with promises of ‘Bee Gees-free Weekends.’

End Of An Era?

When Studio 54 was raided and its owners jailed for tax evasion and drugs possession, it symbolised the party’s end.

Just as the disco decade began in early 1970, so a new era began almost on the dot of 1980 when The Sugarhill Gang crashed into the charts with Rapper’s Delight in the winter of 1979 and early 1980, ushering in the age of hip-hop.

A year later, the launch of MTV switched America on to British synth-pop and New Romantic bands like Duran Duran. John Travolta’s switch from disco to rock’n’roll in Grease even prompted a rockabilly revival.

People still went to clubs to dance, but record companies rebranded their releases from disco to ‘dance music’ or ‘house.’ The music ditched its chintzy strings and camp theatricality for a harder electronic edge.

The Paradise Garage, once the epicentre of disco, led the change and gave its name to a new type of dance music: garage. Gloria Gaynor briefly resurfaced in the new era with the defiant I Am What I Am, but few others tarred with the disco brush were able to make the transition. Even the Bee Gees were never the same again.

Can’t Stop The Beat

In recent years, however, several artists have looked back fondly on the disco era, taking inspiration from NY’s legendary club scene.

The early 00s, French duo Daft Punk led a nu-disco revival with . In 2013, they teamed up with Chic guitarist Nile Rodgers and Pharrell Williams for the extremely disco chart-topper Get Lucky.

While Madonna donned a Saturday Night Fever-style leotard in the video for Hung Up from her 2005 Confessions On A Dance Floor album, which paid homage to the sounds of the Bee Gees and Giorgio Moroder.

2016’s sunny Justin Timberlake smash Can’t Stop The Feeling, meanwhile, wouldn’t have sounded out of place in a disco 45 years ago.

As for the original mirror ball classics, Love Train, Rock The Boat and many others had lost none of their feel-good freshness when they formed the soundtrack to Matt Damon’s acclaimed sci-fi blockbuster The Martian.

And what could have been a more rousing end credits number for that movie than a song that has become a hymn to disco’s own durability, Gloria Gaynor’s I Will Survive.

Douglas McPherson

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!