A dance album you couldn’t dance to, a club classic for when the clubs closed – Blue Lines by Massive Attack truly redefined notions of artist, group and genre. Classic Pop explores the amorphous 1991 debut from the Bristol collective that left an indelible mark on British History… By Michael Leonard.

For music in both the USA and the UK, 1991 was very much a story of how the West won. Stateside, Seattle’s grunge triumvirate of Nirvana, Pearl Jam and Soundgarden saw rock listeners turn their heads towards a new, provincial hotbed of musical creativity. In the UK, it was Bristol, and a new take on ‘dance’ music led by Massive Attack.

Seattle and Bristol have many similarities – both Western ports, ‘outsider’ cities caricatured as rainy and dank, both technological cities, despite their ‘bumpkin’ rep – but musically, they were as different as chalk and cheese… or coffee and rum.

Just as grunge’s breakthrough into the mainstream had its roots in Seattle’s Sub Pop label, so Massive Attack’s ‘Bristol sound’ or ‘trip-hop’ (terms they all hate, of course) grew out of a local soundsystem, The Wild Bunch.

A sprawling collective of DJs, engineers, rappers and graffiti artists emerging from the streets of Bristol in the 80s, The Wild Bunch were more gang than band, but were the springboard for the careers of Milo Johnson (aka DJ Milo/ Nature Boy), über-producer Nellee Hooper (Soul II Soul, Björk, U2) and, of course, Massive Attack.

Massive Attack’s Daddy G remembered the Bristol street scene that birthed The Wild Bunch as “punks, bikers, dreads, you know, just a whole cacophony of people in this one place. It’s surprising how so many mixtures of people in that one place don’t actually erupt… I think a lot of people were into spliffing, so it kept everyone tranquil.”

Just as Seattle’s slackers eventually rose, so did Bristol’s spliffers. But it took time. Even Blue Lines, apart from one single, wasn’t initially a huge hit, reaching No.13 in the UK. Perhaps because, at the turn of the 90s, no one outside of Wild Bunch circles really understood who or what Massive Attack were.

After all, their main spokesman – if the press-shy members had a spokesman at all – was an ex-punk, graffiti-daubing, spiky-haired white boy with an Italian name.

Perhaps it was his own mix of influences that caused Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja to explain, in an early interview with NME: “We haven’t really got a line-up. We’re not governed by bass, guitar, drums and singer. We’re just a loosely based idea. The difference between now and The Wild Bunch is that we’re not fighting for supremacy all the time, we agree to differ…

“The whole of the Blue Lines album was about us being coerced into a studio, and then confronted with trying to make a demo. It wasn’t like we sat around on the piano writing songs together.”

“We were lazy Bristol twats,” Daddy G later recalled. “It was Neneh Cherry who kicked our arses and got us in the studio… I was still DJing, but what we were trying to do was create dance music for the head, rather than the feet.”

The description was totally apt. Blue Lines melded ‘dance’ styles like no other album before it. It was ‘soul music’, shot through with an acute melancholy: rhymes of “No sunshine in my life/ Because the way I deal is shady” or “Don’t need another lover/ I just need, I’m insecure” weren’t the average hip-hop currency.

- Read more: The Bristol Sound – How The West Was Won

The enigmatic Tricky admitted at the time: “I’ve even tried writing hard, aggressive raps. But, at the end of the day, that’s not me.”

It was ‘hip-hop’, but true to the original cut-and-paste ethos which had somehow got lost. Early-90s hip-hop had settled into funk party jams or gangsta chronicles, far from the 80s days when Afrika Bambaataa would mash up funk, punk, rock, Kraftwerk and Apache.

Blue Lines picked up the multimix mantle again, dialling in dub and fusion samples, a didgeridoo and billowing classical strings. Even when Blue Lines sampled classic soulsters such as Isaac Hayes, it turned his music woozy.

And like early hip-hop, the mic was being passed around over the DJ/producers’ beats and breaks: the whispered rhymes of Tricky and 3D, the rich baritone of G, the honeyed soul voices of Shara Nelson and Tony Bryan, the mellifluous roots reggae of Horace Andy.

Throughout its stylistic shifts, Blue Lines sounded familiar enough to be ‘fashionable’… yet, simultaneously, like nothing else you’d ever heard.

“It’s always been the same, music,” 3D said in a 1991 interview in Select magazine. “It’s never been any different. If you listened to a stack of LPs from every era, it would all sound the same to you. And that applies to everything, from rock to indie, house to hip-hop, or even jazz, sometimes…

“Dance music and indie music are the two worst in those fields. Obviously, you get wicked things coming through but on the whole, it’s really bland, really mediocre.

“It’s like that film Amadeus, when Salieri says, ‘I’m the King Of The Mediocre’. That’s what he had resigned himself to and that’s what most music is at the moment. Everyone is content to be mediocre.”

Neneh Cherry, and the people around her, had a bigger influence on the making of Blue Lines than many at first realised. She’d known The Wild Bunch for a few years, and her media connections helped get The Wild Bunch soundsystem onto a tour of Japan in 1986 to be covered by style bible The Face.

- Read more: Jazzie B interview

Cherry’s producer (and soon-to-be husband) was Cameron McVey, who’d go on to become Massive Attack’s manager.

Cherry had debuted on a 1986 ‘hip house’ single by duo Morgan/McVey on the B-side Looking Good Diving With The Wild Bunch, produced by none other than Stock Aitken Waterman, on PWL.

Cherry scored a solo deal, with McVey co-producing. Mushroom is credited with programming on three tracks of her 1989 genre-hopping debut LP, Raw Like Sushi, and appears on decks and keys in the video for Buffalo Stance: (“Looking good/ Hangin’ with The Wild Bunch”).

3D was also onboard, co-writing the follow-up single Manchild, with its hip-hop beats meshing with mournful strings even sounding like a proto-Blue Lines track.

The Wild Bunch had released their own tracks, notably a single for Island/4th & Broadway called Friends And Countrymen, with Shara Nelson on the B-side for a cover of Bacharach/David song The Look Of Love.

But this was The Wild Bunch with Milo and Nellee Hooper still involved, before the latter jumped ship for Soul II Soul’s Club Classics Vol. One).

As 3D, Daddy G and Mushroom morphed into Massive Attack to record themselves, they were partly bankrolled by Neneh and McVey’s (aka Booga Bear) Cherry Bear Organisation. For early Massive, there’s a

The 1990 to 1991 studio sessions for Blue Lines were split mostly between Bristol’s Coach House Studio and Cherry Bear Studios, which was in reality Cherry and McVey’s London flat.

Things didn’t always run sweetly, with Massive eventually calling Cherry Bear “the Poo Room”. Mushroom later explained: “One of Neneh Cherry’s kid’s nappies got trapped in the air vent, then they went away for the summer and we were left to work with this terrible smell. So I guess we’ve got less of a romantic memory of that album than everyone else.”

Nevertheless, a sound was coalescing. Daddy G reflected of the era’s dance scene: “It was all about going getting pilled up. We were like: let’s make some anti-dance music, something that you can sit and listen to. There wasn’t any relaxing music, it was all quite hype- and drug-induced. I think people got bored with that and wanted to make more experimental music.”

- Read more: Making Moby’s Play

Many fans of Blue Lines didn’t (or don’t) realise just how much of it was heavily sampled and looped from previous artists’ tracks.

The album credits were very ‘meagre’, with some composers of the original tracks receiving co-writing credits, while individual source tracks aren’t mentioned on the sleeve. Others – even Mahavishnu Orchestra – only make an ‘Inspired by’ list, while the sole outside instrumentalist credited is bassist Paul Johnson.

Yet that was simply hip-hop’s MO at the time. Only insiders would’ve known that their equipment cache was little more than their DJ decks, an Ensoniq EPS sampling synth, a Yamaha drum machine and a Numark mixer.

Daddy G explained later that Blue Lines was “completely from a DJ perspective. We’re gonna make a record of our favourite sounds and influences and it was quite heavily sample-based. It was quite imaginative the way we did something with it.”

As 3D said of opener Safe From Harm: “Working with a sample like that, you can’t go wrong. Even as a loop with no vocals in it, as soon as you loop that up and listen to it, you’re going, ‘Yeah’. It just has a total groove.”

On its April 1991 release, an effervescent NME review wrote that: “After Blue Lines, the boundaries separating soul, funk, reggae, house, classical, hip-hop and space-rock will be blurred forever.”

21 years on, Pitchfork concurred, comparing listening to Blue Lines to “reading an old William Gibson novel that describes the then-near future, which is now the present, with unsettling precision. Nearly every song offers a sound currently in use in music’s taste-making leading edge.”

The influence of Blue Lines was, indeed, massive. Its success shone a light on Portishead (whose Geoff Barrow worked as a mix intern on Blue Lines), and the slew of artists in its wake – Morcheeba, Sneaker Pimps and more.

Moby, Leftfield, DJ Shadow, Björk, Groove Armada and Nightmares On Wax were clearly listening hard. Jamie xx seems to still be listening right now.

The notion of a ‘core’ production team with everrevolving guest vocalists was also soon a norm… Gorillaz have picked up the template.

- Read more: Focus On: Bristol

While it’s rightly seen as one of the 90’s most pioneering albums, the real strength of Blue Lines is its timelessness. It still sounds new, like the 21st century a decade too early.

Massive Attack as an idea has evolved; more live instruments, darker textures, even less danceable, even more menacing… even though, at times, the ‘group’ has been 3D alone. But it’s arguable that they were never stronger than on this bolt-from- the-blue debut. It’s angsty and gloomy, yet it remains a beautiful, essential album.

“Massive Attack and Blue Lines are part of the UK’s musical DNA,” says Labrinth (Timothy McKenzie), the fêted English producer/singer/ rapper/multi-instrumentalist.

“They’ve had a huge influence on UK production. They’ve influenced music around the world, of course, but the UK more than anywhere.”

Even Massive Attack’s Daddy G, not usually prone to bragging, concurs that Blue Lines was a masterstroke, saying: “I think it’s our freshest album. We were at our strongest then.”

Massive Attack – Blue Lines: The Songs

1. Safe From Harm

One of the first four songs produced for Blue Lines (alongside Be Thankful For What You’ve Got, Lately and the not-included Any Love) and the first recorded with singer Shara Nelson. 3D favoured it, as he felt the other three songs were too retro and soft. Nelson’s opening words of “Midnight rockers/ City slickers/ Gunmen/ And maniacs” and its black and white video set the album’s unnerving, claustrophobic tone. Perhaps more so than any other Massive Attack chart hit, Safe From Harm owes a major debt to its primary sample, from Billy Cobham’s Stratus off his 1973 fusion album, Spectrum. 3D’s “I was lookin’ back to see if you were lookin’ back at me to see me lookin’ back at you” lyric is lifted from David Essex’s Streetfight, from 1973 album, Rock On.

2. One Love

Blue Lines’ second track turns a meditative two-second piano lick from the Mahavishnu Orchestra plus some select Isaac Hayes into a crawling reggae mantra. It sounds threatening, despite Horace Andy’s lyrics being a hymn to monogamy. The Jamaican singer has been the only outside vocalist to feature on every Massive Attack album.

3. Blue Lines

One of the most straightforward hip-hop cuts on Blue Lines, the title track is rapped over a well-used 1974 break by Tom Scott And The LA Express. They’re not credited and neither are The Blackbyrds. Primarily a duet of 3D and Tricky, with some bizarre lyrical references: “(Take a walk) Billy, don’t be a hero”, “(Excommunicated from) the brotherhood of man”, the “sound of silence” and “walking on sunshine” could all be pop references from Del Naja’s youth. 3D also references his graffiti days, which he largely gave up for Massive Attack…or maybe didn’t, if you’re a Banksy conspiracy theorist.

4. Be Thankful For What You’ve Got

It was Daddy G’s idea to cover this 1974 R&B tune by one-hit wonder William DeVaughn. Tony Bryan, who appeared on Massive Attack’s pre-album 1990 single Any Love, returned to sing. The track was remixed for US release, by Chris Stokes and Cyrus Melchor of New Jack Swing trio Immature, but never commercially released. 3D thought the soul cover was a bit too musically straightforward for Massive Attack but felt an affinity for the lyric. He told NME: “It’s a sentiment for the 90s. What’s the point in killing people for their Nikes? We’re living in a time where nobody can be satisfied with what they’ve got because of the media. You’re bombarded with stuff to desire.”

5. Five Man Army

Blue Lines’ biggest dub track. Based on the 12” dub mix (by Lewin Bones Lock) of Five Man Army (1982) featuring Dillinger, Wayne Wade, Trinity, Al Campbell and Junior Tamlin. With Andy, Tricky and Williams, there are also fi ve vocals on Massive’s track. The 1972 Al Green drum lick was sampled around the same time by Eric B & Rakim on Mahogany (1990). G references the Wild Bunch tour of Japan and it closes with Horace Andy reprising Money Money and the title track of his 1969 Studio One debut LP, Skylarking.

6. Unfinished Sympathy

Nelson was responsible for the words and vocal melody of Blue Lines’ most ambitious recording and its biggest hit (No.13 in the UK, No.1 in Holland). “Bits of the melody came into my mind,” she told Spin. “I couldn’t shake it, so I took a break from recording, had a cup of tea, stood in the corner and started singing it to myself to see if I could piece it together.”

The strings were the idea of co-producer Jonny Dollar, who first played a synthesised version, then brought in a 40-piece string section conducted by string arranger Will Malone that was recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London.

Strangely, the song has no bassline, instead using the orchestra’s double basses and the propulsion of the gradually unfurling string arrangement. 3D later recalled: “It was an exercise in deconstruction – a song that came with verse-bridge- chorus, these three classic songwriting structures, but we ended up leaving the chorus out and leaving a big space behind, and getting Will Malone to score the strings and build this giant swell of music, because it suddenly had space. This is what gave the song its expanse.”

Ironically, Mushroom later complained of Nellee Hooper’s remix of Unfinished Sympathy, saying, somewhat ironically: “You don’t hear of people remixing Led Zeppelin or the Mahavishnu Orchestra.” But maybe his memories of it have never been all that fond? While still being largely bankrolled by McVey/Cherry’s Cherry Bear Organisation, since Massive hadn’t budgeted to pay for a 40-piece orchestra at Abbey Road, Mushroom had to sell his Mitsubishi Shogun.

7. Daydreaming

The demo of Daydreaming got Massive Attack signed to Circa Records (also Neneh Cherry’s label) and was released as a single in 1990. On it, 3D and Tricky fuse lyrical ideas on past house parties, drugs and 1980s urban life. Of the looped sample, from his 1984 LP Echoes, Wally Badarou (of Island Records’ Compass Point All Stars) said: “It was done with my negotiated consent. I got properly credited, so I can’t see that it could ever be a rip-off. Given the magnitude of their success afterwards, it sure looks like something one can only be proud to be a part of.”

8. Lately

Again, the main sample dominates the music, while Mushroom’s DJing skills for beat-matching and scratching come to the fore. It includes a sample of Lowrell Simon’s Mellow Mellow Right On, which hit No.37 in the UK charts in 1979.

9. Hymn Of The Big Wheel

Neneh Cherry co-wrote this track largely with 3D: they’d worked together on her Manchild single. 3D told NME in 1991 that it “does build a bigger picture than the rest of the tracks on Blue Lines because the rest are kind of unfocused – they just drift around in their own way, rather than paint an obvious picture. We’re as worried about things like pollution as everyone else, it’s just we don’t want to write about it so obviously. We ain’t got no solutions to the problems. Just questions, y’know?”

Massive Attack – Blue Lines: The Players

Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja

A pioneer of stencil graffiti and the co-designer of all of Massive Attack’s live lighting shows, Robert Del Naja has also collaborated with Unkle on the albums Never, Never, Land and War Stories, Guy Garvey, Thom Yorke and Jean-Michel Jarre.

Andrew ‘Mushroom’ Vowles

Andrew Vowles left Massive Attack shortly after the release of Mezzanine, the band’s third album, reportedly due to creative differences. He also worked as a co-producer on Neneh Cherry’s 1989 debut Raw Like Sushi.

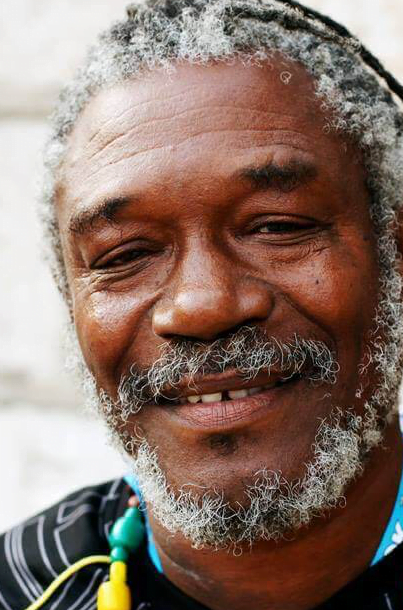

Grantley ‘Daddy G’ Marshall

Emerging from the soundsystem scene in Bristol’s St Paul’s neighbourhood in the early 80s, he worked as a DJ at the Dugout nightclub as well as in the city’s Revolver Records shop. He released a DJ-Kicks compilation in 2004 that’s well worth investigating.

Shara Nelson

Massive Attack’s main female vocalist on their debut album. Her solo album What Silence Knows was nominated for the 1994 Mercury Music Prize.

Horace Andy

The reggae veteran has collaborated on all five of Massive Attack’s studio albums.

Tricky

Tricky left the band after the release of sophomore LP Protection, going on to a prolific solo career that included the acclaimed debut Maxinquaye from 1995.

Jonny Dollar

An architect of trip-hop, Dollar co-produced Blue Lines and Neneh Cherry’s Raw Like Sushi. He died of cancer aged 45 in 2009.