Focus On: Bristol

By Classic Pop | April 3, 2023

It may have a reputation for being the laid-back home of trip-hop, but punk had a profound effect on Bristol, a city where seeing a Pop Group could be an assault on the senses… By Jonathan Wright

It may have a reputation for being the laid-back home of trip-hop, but punk had a profound effect on Bristol, a city where seeing a Pop Group could be an assault on the senses… By Jonathan Wright

The suggestion that The Pop Group may have been a huge influence on the music of Bristol causes a flicker of confusion to pass across the face of John Parish.

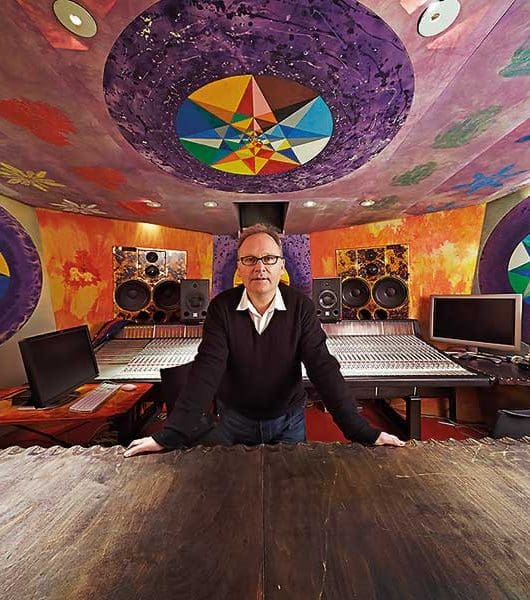

At a guess, this isn’t because the musician, producer and longtime PJ Harvey collaborator disagrees with the idea, it’s because he’s momentarily flummoxed by its narrow focus.

“They were an influence on everybody that came along afterwards, not just in Bristol, but all over the place,” he points out.

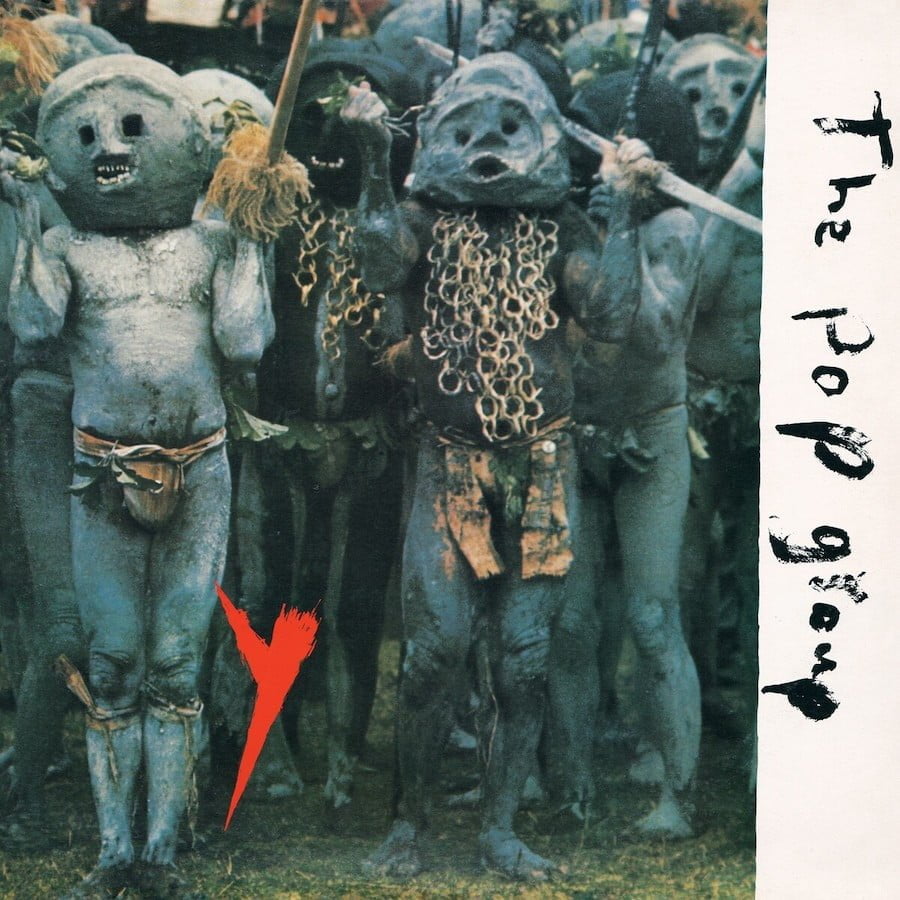

He’s absolutely right, of course. The influence of The Pop Group’s first recorded salvos – most especially the excoriating 1979 singles She Is Beyond Good And Evil and We Are All Prostitutes, politically charged slabs of punk-funk that made the Gang of Four sound restrained – is still playing out as the band’s records are discovered by new generations of musicians.

A COLLISION OF CULTURES

It says much about a city, what Guardian political journalist and cultural critic John Harris (The Last Party: Britpop, Blair And The Demise Of English Rock), has called “mischievous, multicultural Bristol” that The Pop Group embody something central to the city’s spirit.

It’s a spirit of cultures colliding, experimentation, doing stuff because it’s interesting, ideas that would later run through the music that came to be defined as trip-hop.

“[The Pop Group] were a fantastic encapsulation of everything – protest, punk, rebellion – that pop should be,” adds John Parish. “There wasn’t much in the way of catchy tunes maybe, but beyond that they had everything.”

As to The Pop Group’s story, it began when, to quote frontman Mark Stewart from the documentary Unfinished: The Making Of Massive Attack, “Punk… blew the doors open”.

Coming back from seeing first-generation Bristol punk band The Cortinas at London’s Roxy in 1977, Stewart and friends decided to take to the stage themselves – initially at unpromising venues such as Barton Hill Youth Centre.

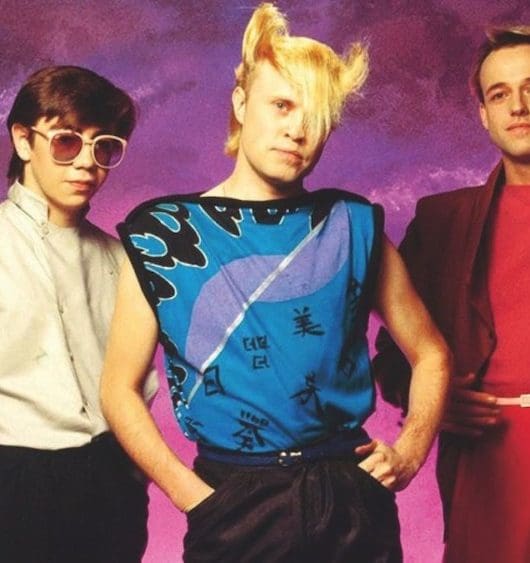

While The Cortinas, who landed a contract with CBS, were essentially a clattering rock band, The Pop Group from the oft-incorporated elements of jazz, reggae, dub, funk and sound system culture.

This was music that reflected inner city Bristol, with its strong African-Caribbean community centred on St Paul’s, as much as it reflected the experimental spirit of the post-punk era.

But The Pop Group burnt brightly. In 1981, beset by internal wrangling, they split.

Stewart would subsequently spend much of the 1980s working with the On-U Sound collective on albums with cheery titles such as When The Veneer Of Democracy Starts To Fade. (Bristolian Gary Clail had a hit, entitled Human Nature, with On-U Sound in 1991).

The Pop Group bassist, Simon Underwood fetched up in Pigbag, who reached No.3 in 1982 with Papa’s Got A Brand New Pigbag. Guitarist Gareth Sager and drummer Bruce Smith, later to join Public Image Limited, formed Rip Rig + Panic.

The Pop Group bassist, Simon Underwood fetched up in Pigbag, who reached No.3 in 1982 with Papa’s Got A Brand New Pigbag. Guitarist Gareth Sager and drummer Bruce Smith, later to join Public Image Limited, formed Rip Rig + Panic.

Deriving their name from a Roland Kirk album, the band tried, not always successfully, to fuse the spirit of improvisational jazz with post-punk, and were fronted by a teenage bag of energy called Neneh Cherry. More of Cherry later…

Meantime, also at the turn of the decades, The Korgis enjoyed a one-off hit with Everybody’s Gotta Learn Sometime, which made No.5 in the UK singles chart and No.18 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1980.

Formed from members of Bristol rockers Stackridge, their blend of pop, new wave and synthpop led to four studio albums and Everybody… even featured in Michel Gondry’s movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind when it was covered by Beck.

PREPARING FOR TAKE-OFF

For now, the deeper story here isn’t one of individual projects, but the way The Pop Group – along, let’s forget, with plenty of fellow travellers documented at the fabulous Bristol Archive Records website – had energised the Bristol music scene and opened up possibilities.

One of those who was active from the late-70s, initially fronting post-punk band Art Objects, the band that mutated into The Blue Aeroplanes, was poet Gerard Langley.

“It seemed what you did didn’t matter,” he says, “it was the fact that you were doing it and you could do pretty out-there kind of stuff.

“The first-ever Aeroplanes gig, we stretched a sheet of polythene between us and the audience, so all you could see were these shapes moving round behind a sheet of polythene.

“After about three songs, when people were thinking, ‘Are they going to spend their whole time behind that fucking screen?’ we did an instrumental, and our dancer [Wojtek Dmochowski] had a Stanley knife and started cutting through it.

“It was really good fun to do stuff like that. I suppose you could take it seriously, but I don’t think we did, it was just funny.” Bristol, he adds, “likes one-off events and it likes backstreet things, and it likes things that people don’t know very much about.”

From a different angle, John Parish remembers the kinds of gigs his group Automatic Dlamini used to play in the 1980s.

“We opened for bands like Black Roots and Talisman, which at the time didn’t see remotely odd to me,” he says. “Now, that would seem quite an unusual combination, but it seemed like there were only a certain number of places to play and people would just put mish-mashes of bands on.

“Or we’d be on with Peter And The Test Tube Babies, very peculiar pairings. I used to like that, it was interesting.”

Nonetheless, there was a divergence in the late-80s Bristol scene in that, like most parts of Britain, it had a recognisable indie scene (Parish: “that became more clearly defined from 1986 onwards, I would say”).

Bristol, after all, was the home of Sarah Records, formed in 1987 by Clare Wadd and Matt Haynes, and associated with a kind of post-Orange Juice, jingly-jangly guitar music dubbed C86 after a cassette given away with the New Musical Express – think releases by the likes of The Sea Urchins, The Orchids and The Field Mice.

These were bands routinely dismissed through the Britpop era and beyond via the dread word ‘fey’, yet a reassessment of this era has lately, and rightly, begun.

It was important to Wadd and Haynes that Sarah was based in their adopted home, a city they loved, that you didn’t need to move to London just to put out music.

This is one reason the labels on its 7” singles featured scenes from the city. Sarah refused to put tracks released as singles on albums, except compilations.

Wadd constantly challenged what she saw as the sexism of the British music inkies. A press advert promoting forthcoming releases also denounced capitalism.

Sarah wasn’t fey, it was, to employ John Harris’ description of Bristol, gloriously mischievous.

HAVING FUN WITH THE FORM

A similar sense of serious playfulness runs through many Bristol bands of the 1980s and 1990s, whether you’re talking indie heroes such as The Brilliant Corners and Strangelove, or, from a different angle in this context, Bananarama, a trio far more self-aware than they’re often given credit for (more industry sexism to the fore…) and with firm roots in the city.

And yet to see the Bristol scene in the 1980s as being just about divergence between indie and something we used to call dance music is rather to miss the point.

Gerard Langley tells a story about former Blue Aeroplanes guitarist Angelo Bruschini, who now performs with Massive Attack.

It revolves around Massive mainman Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja raving about an indie EP called 4 Alternatives released on Heartbeat Records in 1979. Bruschini pointed out that he performed on the record, something Del Naja thought couldn’t be true.

But Bruschini was indeed on the EP, as the teenage guitarist with The Numbers. Del Naja, it’s worth noting, was also in the audience at early Pop Group shows.

Again and again, these kinds of connections play out in the story of Bristol music, suggesting a certain fluidity. While she wasn’t referring directly to Bristol, it’s a vibe Neneh Cherry summed up when she talked about Rip Rig’s demise.

“I don’t remember us splitting up,” she once told Spin Magazine, “but there was an overspill into another overspill.”

CAN YOU DIG IT?

In the 1980s, one of the major scenes of overspill, an appropriate word considering the state of its notoriously sticky floors, was the Dug Out on Park Row, on the edge of Clifton (close to Revolver Records on Clifton Triangle, the store immortalised in Richard King’s acclaimed memoir Original Rockers).

“[It had] what was known as the musicians’ bar, where everyone in all the punk and new wave bands hung out,” recalls Gerard Langley.

“My girlfriend worked behind the bar so I was there three or four times a week. But everyone was there and everyone knew everyone else.”

Latterly, the venue has become famous for its association with The Wild Bunch. Anchored in the sound system culture of St Paul’s, those who performed with The Wild Bunch included Nellee Hooper, Robert Del Naja, Grant ‘Daddy G’ Marshall, Andrew ‘Mushroom’ Vowles and Tricky.

“Being DJs as The Wild Bunch, we sort of made a name of ourselves for the crazy collection we used to have, and we would mash it all together – jazz, disco, hip-hop, reggae, punk,” reflected Daddy G in 2010, talking to US website Buzznet.

Another ingredient was early hip-hop with, according to the Unfinished documentary, US releases finding their way to the west of England in part through tapes brought back by Mark Stewart’s visits Stateside.

“Hip-hop was the first thing that encapsulated what we did with The Wild Bunch,” Daddy G continued in the Buzznet interview.

“What we were doing with the sampler when we first learned it was definitely copying the way American hip-hop artists went into the studio to create beats that worked for them.”

The collective’s burgeoning reputation, along with support from Neneh Cherry and The Face magazine, secured The Wild Bunch a trip to Japan in 1987.

There, they promptly imploded, with Del Naja returning home early. Hooper and fellow member Miles ‘DJ Milo’ Johnson signed as The Wild Bunch with Island offshoot 4th & Broadway and released a couple of singles, but the end was nigh.

- Read more: The Bristol Sound – How The West Was Won

THE WORLD IS WAITING

Except things were really only just beginning. In 1989, Hooper co-produced one of the seminal British R&B albums, Soul II Soul’s cheekily named, Grammy-winning debut, Club Classics Vol. One, with the band’s frontman Jazzie B. It was a prelude to a career that’s taken in work with the likes of Sinead O’Connor, Björk and U2.

Meantime, Del Naja, Marshall and Vowles reconvened as Massive Attack. In 1988, the band self-released their first single, Any Love, produced by Smith & Mighty.

With the band signed to Circa Records, Blue Lines, which took around eight months to record (Del Naja: “with breaks for Christmas and the World Cup”), followed in 1991.

In an era when trip-hop is associated with adverts and dinner parties, it’s worth taking a step back to remember how radical and even dangerous it sounded 30+ years ago, less than a year after Margaret Thatcher had been forced to resign and events such as the 1980 St Paul’s riot, which broke out after a police raid on the Black and White Café, were fresher in the memory.

“It’s like walking around [Bristol’s] City Road a little bit out of it after carnival or something and just hearing all these things washing over you… it’s real,” Mark Stewart has noted.

There’s a neat symmetry to the way Rip Rig’s Neneh Cherry, partner to producer Cameron ‘Booga Bear’ McVey, was a driving force behind the album.

“We were lazy Bristol twats,” Marshall later confessed. “It was Neneh Cherry who kicked our arses and got us in the studio. We recorded a lot at her house, in her baby’s room. It stank for months and eventually we found a dirty nappy behind a radiator.”

Cherry co-wrote Blue Lines’ closing track Hymn Of The Big Wheel that also featured soul singer Shara Nelson and reggae vocalist Horace Andy prominently.

- Read more: Jazzie B interview: “Music was so stale and stagnant when Soul II Soul came along… we caused a stir”

In a sense, this was returning a favour because Del Naja and Vowles both contributed to Cherry’s multi-platinum 1989 debut, Raw Like Sushi.

If the emergence of Massive Attack was remarkable enough in itself, it’s come to be seen as just a prelude to a wider movement. In 1994, Portishead’s Dummy was released.

The debut from Geoff Barrow (who worked as an intern and trainee tape operator at Bristol’s Coach House when the album was mixed and mastered), jazz-influenced guitarist Adrian Utley and singer-songwriter Beth Gibbons was downbeat and eerie.

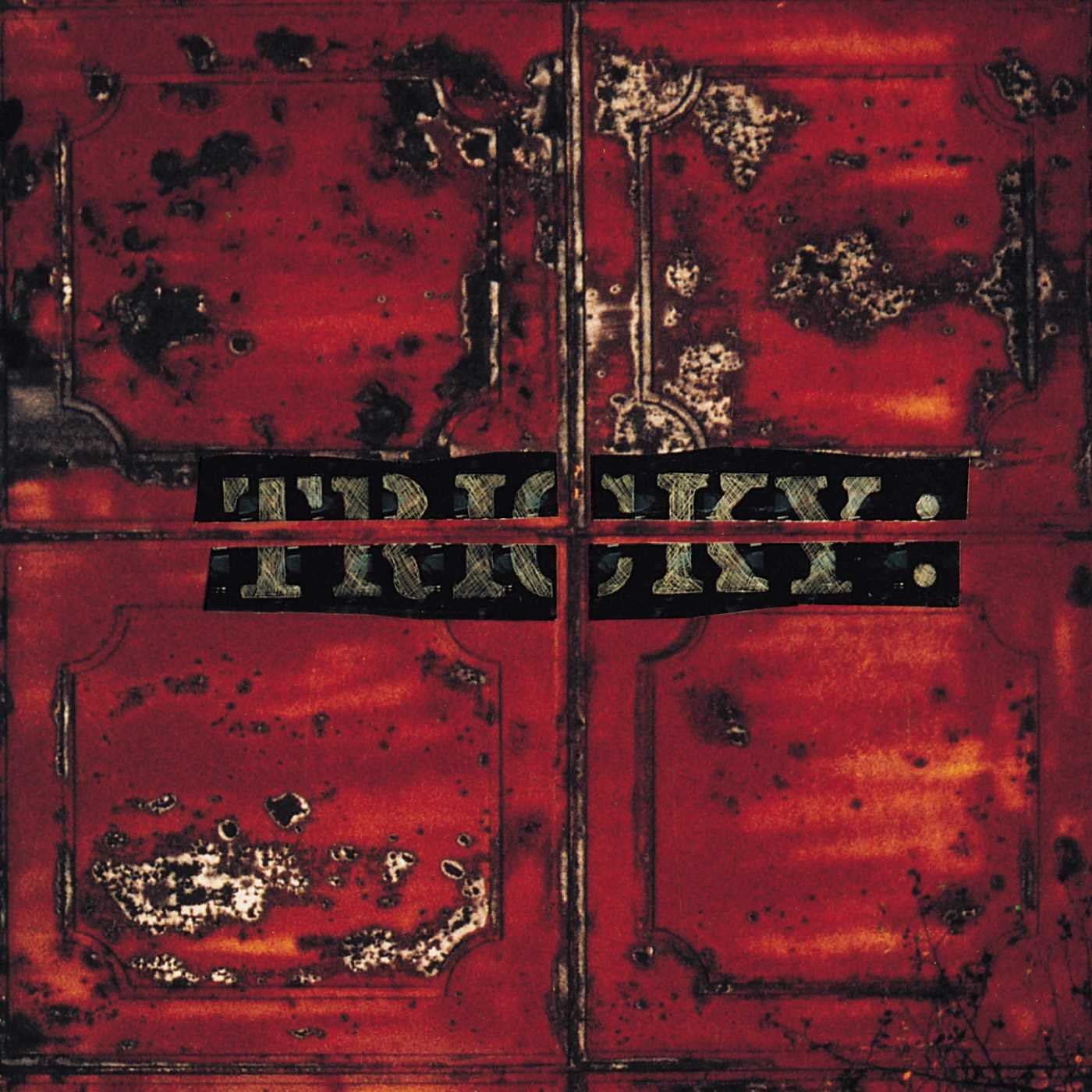

A year later, the Bristol trip-hop triumvirate was completed in the public’s imagination by Wild Bunch veteran Tricky, a man Mark Stewart, apparently affectionately, has described as “an obvious nutter”.

Tricky’s debut Maxinquaye (1995) was a paranoid, dub-influenced masterpiece that featured singer Martina Topley-Bird prominently.

Tricky’s debut Maxinquaye (1995) was a paranoid, dub-influenced masterpiece that featured singer Martina Topley-Bird prominently.

Which, as Gil Gillespie archly notes in the ‘Bristol Beat’ section of The Naked Guide To Bristol came as a bit of a shock considering he was regarded as “Massive’s equivalent of Sid Vicious”.

Subsequently, the city’s musical profile has never quite matched its 1990s heights, although there have been moments: notably Roni Size’s Reprazent taking drum’n’bass into the mainstream with the Mercury-winning New Forms, an album that leant heavily on the pioneering work of Bristol’s Smith & Mighty.

Electronic acts Kosheen and Fuck Buttons as well as singer-songwriter Beth Rowley also went on to achieve chart success in the Noughties and 2010s.

Which isn’t to say there’s not plenty going on. In the week Classic Pop meets John Parish for lunch, for instance, he’s both gearing up to go on tour with PJ Harvey.

“I think [Utley is] a kindred spirit in a way,” says Parish. “If you ask him to do something interesting, he’ll probably look on it favourably and do it because he’s interested.”

The Bristolian spirit of collaboration and having a go because it’s interesting, it seems, is alive and kicking. As, in its way, is a stubborn spirit of rebellion kicked into life by punk and which still runs deep in Bristol’s musical DNA.

As Mark Stewart notes of Massive Attack in Unfinished after having a quick grumble about the band’s own notorious reluctance to talk about their work: “They are proper punk, but Bristol punk.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!