The Establishment first ignored it, then embraced it, before finally trying to ban it… but the charts were heated up in the late 80s by a string of classic acid house music tunes during the Second Summer of Love. By Johnny Sharp

“It’s club music. This isn’t what people are actually listening to.” That’s what Coldcut’s Matt Black and Jonathan More were told when their innovative floor-filler Doctorin’ The House swooped into the Top 10 of the national charts, and they asked why Radio 1 and Top Of The Pops were ignoring it.

To be fair, you could have forgiven uninitiated listeners for doing a double take. Doctorin’ The House was patched together with samples from kitschy TV-drama dialogue, scratching, snatches of old rap and reggae records and a squelchy, hyperactive bass sound, all underpinning a stirring but lyrically baffling soul vocal from a previously unknown frontwoman.

But in truth, none of this was anything new to the tens of thousands of kids that were flocking to club nights such as London’s Shoom and The Trip and Manchester’s Thunderdome and Haçienda, and swarming into illegal warehouse parties, not to mention the nightlife of Mediterranean hippy meccas like Ibiza.

In those places, the same old scene of ‘no-T-shirts-no-trainers’ meat markets pumping out chart hits had long since been eclipsed by a new kind of dance beat, fuelled by something a little more potent and uplifting than Malibu and lemonade.

Take a trance on me

As the spring of 1988 turned into summer, the same sounds would flood out of the clubs, into the charts and throughout youth culture in what would become known as the Second Summer Of Love.

In fact, things had actually been stirring for a while. The ‘Belleville trio’ of Detroit schoolmates Derrick May, Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson had long been blending electronic minimalism with r’n’b grooves (“George Clinton and Kraftwerk trapped in an elevator” was one description they offered), while a new strand of soul coming out of Chicago was using Roland bass synthesisers and looped samples and being labelled ‘house’ music.

Londoner Mark Moore was one British DJ who played those records in the mid 80s, given a free hand on the decks at Philip Sallon’s Mud Club and gay mecca Heaven. “We didn’t even know this was called house music at the time,” he says. “It was just mad electronic music.”

Early UK hits from the otherwise low-profile US house scene were soon inspiring British DJs and producers such as Moore. Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley’s Jack Your Body had been a surprise smash in the UK in January 1987, becoming the first track ever to reach the top spot without being played on Radio 1. Its synth-driven minimalism foreshadowed how the genre would evolve.

Yet many pop fans regarded such records as quirky, isolated hits, as Moore points out: “Even when M|A|R|R|S’ Pump Up The Volume and Bomb The Bass’ Beat Dis came out [in summer ’87 and early ’88 respectively], people thought they were just novelty records – this is going to disappear again and we can get back to good old Kylie and Jason…”

Yet those tracks’ simple structure was inspiring listeners in much the same way as punk’s ‘here’s three chords, now form a band’ ethos had a decade previously. Ed Stratton was one early convert, a Capital Radio engineer intrigued by house and also captivated by the increasingly inventive use of samples in hip-hop.

“We were really excited by the new house tracks coming over from the US,” says Stratton, “and when I heard Jack Your Body I was blown away – such an incredibly simple construction, all electronic, and it struck me as not very difficult to put something like that together.

“Before that, I’d also been inspired by seeing what Paul Hardcastle did with 19 – an electronic record thrown together with samples. When you thought about what you could do with samples, you could see no end to it – anything was possible.”

Ed teamed up with an old college friend, Vlad Naslas, and as Jack ’N’ Chill, they put together one of the first British-born house hits, The Jack That House Built.

What the doctor ordered

Around the same time, Simon Harris, who was trying to help UK hip-hop off the ground with his label Music Of Life, was playing with a Studio 440 sampler when he created Bass (How Low Can You Go), a house track built on Public Enemy’s clarion call Bring The Noise.

Good ideas often occur to creative people at the same time, and while Harris and Stratton were hatching their plans, the Coldcut duo were making their mark as sample-magpie producers and remixers (most notably of Eric B. & Rakim’s Paid In Full, a hit in autumn 1987).

But when they released Doctorin’ The House, featuring the vocals of a striking blonde-cropped chanteuse named Yazz, it was clear that there was a seismic shift happening in UK pop music. If only the gatekeepers of the charts would take notice…

“It just isn’t music,” traditionalists would protest of the new sample-happy strand of pop (a phrase Coldcut would later co-opt for their publishing company, Just Isn’t Music). After all, they reasoned, if you didn’t have to know how to play conventional instruments, and just needed to cobble together other people’s sounds, where was the skill in that? But while the industry may have been baffled, the punters understood.

“There was a massive wave of people having a life-changing cultural-consciousness experience,” Matt Black explains, “not just in clubs, but at raves and warehouse parties. And that was why they were buying these records – they wanted to have that peak experience cemented in their memory.”

As more and more house records poured out of the clubs and raves and into the charts, house acts began to challenge more traditional pop outfits in terms of sales and profile. At first, such acts were caught on the hop by their own success, and had to hastily cobble together something resembling a stage act in order to mime their hits on TV.

Simon Harris at least lucked out with the video for Bass (How Low Can You Go), as he explains. “It was the World DJ Convention and Public Enemy’s Flavor Flav and Professor Griff were in town, so we got them, plus DJs like Tim Westwood and Dave Pearce, to goof around on camera.”

This also reflected a collaborative, encouraging vibe on the scene, refreshingly free from rivalries and jealousy. “Griff was producing one of our groups, She Rockers [featuring future star Betty Boo] and when I put it together, Pete Tong (then running FFRR) said he liked the sample. I said: ‘Get Griff to play it to Chuck D and get permission – and Chuck immediately said: ‘That’s cool’. So it felt like we had the blessing of the hip-hop community to make them part of it.”

Coldcut were well-known on the scene by this time, but like many other DJs, they weren’t teen-idol material. “The NME called us ‘unlikely popstars and they know it’, and that just about summed it up,” laughs Black.

Ed Stratton looked even less suited to the limelight. ‘’We made a video but we weren’t in it, and that’s what Top Of The Pops played, but then we were invited to appear on the rival pop show, The Roxy. Me and Vlad were both mid-30s, I was starting to lose my hair, so I had to make best of it [behind a mainframe-sized computer console, bashing away on a keyboard in a baseball cap, looking more like an IT consultant than a pop star], and then they had this body-builder guy in the middle of the crowd on a podium doing Mr Universe moves and robotics.

Pretty surreal, but it was exciting to be in the green room with the likes of Gary Numan and Bros. I always remember, Numan turned up with his mum!”

- Read more: Inside the Ministry of Sound

- Read more: Top 20 80s house hits

S’express delivery

“When it came out, I think some people in the industry just thought, ‘oh god, here comes another of those bloody records!’,” laughs Mark Moore, who had produced the record with Bomb The Bass collaborator Pascal Gabriel for house-friendly indie label Rhythm King.

“We went into the charts on club play, and then up to No.3, and at that point, I think radio thought, ‘we’d better start playing this, or we’re gonna look pretty stupid’. And I think that was the start of people in the industry really beginning to take house music seriously.”

It probably helped that Moore’s mob offered more traditional-pop visual glitter to draw people in. “We were kind of Top Of The Pops-ready, even though we weren’t expecting to get on there,” Moore says, “because we were colourful people. I just got the most show-offy people I knew to join the group!”

Meanwhile, one bona-fide homegrown star was already emerging in the shape of Yasmin Evans, aka Yazz. When she followed up her appearance on Doctorin’ The House with another Coldcut production under the name Yazz And The Plastic Population (Coldcut’s typically ironic choice of name, referencing the populism of the music and its allegedly artificial nature), The Only Way Is Up hit No.1 for five weeks in August 1988. Fame was hers for the taking as The Second Summer Of Love hit its peak.

An Amazonian former catwalk model, Yazz was striking enough before she visited a hair salon to tackle the ‘fuzzy fireball’ she had on her head. “I remember walking into Vidal Sassoon in the West End,” she told author James Arena. “I told [the hairdresser] to cut it all off and dye it blonde. I think she thought Christmas had come early!”

One of the faces of ‘88 was born, and the song she took to the top seemed to epitomise the joyous, indefatigable positivity of this new pop movement. The Only Way Is Up may have been a revamped soul tune from the turn of the 80s, but its housetastic overhaul made for one of the most euphoric pop anthems of the age.

“The lyrical content reflected where most of the UK was at,” she said. “In a bad recession, and people had been hit very hard… the song leant into their circumstances, offering a sense of hope.”

Hate the game

Meanwhile, some of the artists who had inspired the first wave of house were also deservedly seeing their profile go through the roof. Derrick May’s Rhythim Is Rhythim, along with Chicago House veteran Larry Heard, aka Mr. Fingers, had already helped blueprint the more sweeping, soulful sub-genre of deep house, but May’s old mucker Kevin Saunderson showed the most striking pop sensibility when he formed Inner City with vocalist Paris Grey.

“My vision with Inner City was to make more song-oriented music that people could sing to and dance to,” he says, “but I wasn’t specifically trying to make a hit. Big Fun was an instrumental and I knew I wanted a vocalist.

“I ran into my friend Terry ‘Housemaster’ Baldwin and he said: ‘You know, my singer could kill this’, and he introduced me to Paris. She came up with a vocal line and sang it over the phone to me, and I just loved it.”

Yet Saunderson still looks a touch uncomfortable in the background of their early performances and promo shots, and that was typical of the people behind the first wave of big house hits. Unlike the traditional pop stars, the new breed invariably hadn’t sought fame, and didn’t feel that comfortable with it once they got it.

Even the obviously photogenic Yazz soon became disillusioned. “You find yourself believing that your value or weight as a person is judged upon performance,” she said. “I just wanted to retreat into the studio and not promote the records. I loved music. I hated fame.”

“Once we were expected to play the game, we started to lose interest,” says Mark Moore. “On the Christmas edition of Top Of The Pops, for instance, they censored the opening sample, ‘Enjoy this trip’, and Michelle, our singer, sat sulking on the floor in protest. We wouldn’t mime our instruments properly, we didn’t take it seriously… and they didn’t like that. Ha!”

Meanwhile, the usual approach – of following up big tunes with something in the same vein – didn’t appeal. “As soon as there was a formula to follow, we wanted to rebel against it,” says Moore.

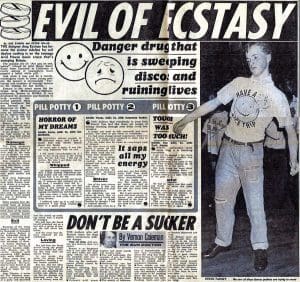

By now, different styles were developing within the house genre. While the minimal trance textures and Roland TB-303 sound were the defining features of acid house, the mainstream press began to refer to all new music played at clubs and raves as ‘acid house’.

It was a broad church, though, encompassing the ‘hip house’ side of the genre exemplified by Simon Harris and The Beatmasters, techno-informed strands such as Humanoid’s brutally brilliant Stakker Humanoid and the more transcendent strains of A Guy Called Gerald’s Voodoo Ray.

Transatlantic trax

House hits were also making a dent in the US charts, showing up meaningless notions of ‘black and ‘white’ music for what they were, as well as changing the scene back in house music’s original home country.

“Me, Juan (Atkins) and Derrick would have around 3-400 people coming to listen when we were DJing in the mid 80s,” says Kevin Saunderson, “and the music scene was very segregated – if you were black, you were expected to play music for black people only. So when hits like Big Fun started bubbling in the UK, people back home began to see there was an opportunity there, without the obstacles that’d been in the way in the US.”

Once unashamedly populist cuts such as D Mob’s We Call It Acieeed hit the Top 10, house music and its gnarlier acid house offspring were fast turning into the defining pop movement of the late 80s. And even if tabloid outrage, dodgy drugs, criminal opportunists and police rave crackdowns would mean the scene was never quite as innocent and friendly again, that incredible summer would help shape pop music for decades to come.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.