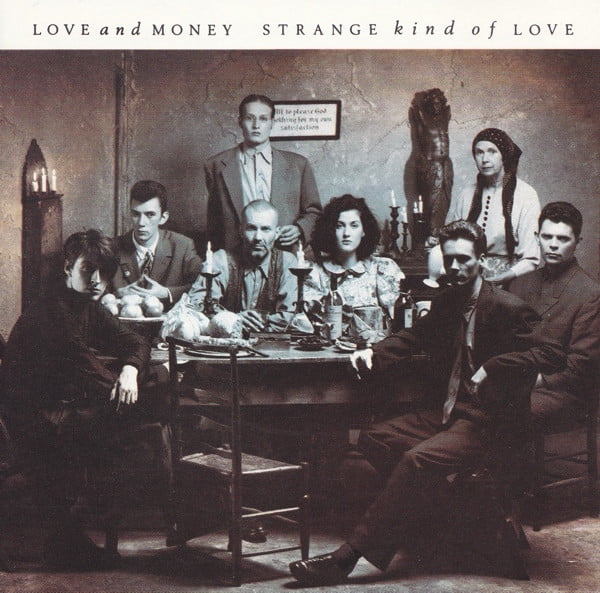

Love And Money – Some Kind Of Love cover

They didn’t score any major hits, but Love And Money remain one of the most fondly-remembered Scottish bands of their era. Their sleeper classic from 1988, Strange Kind Of Love, is Exhibit A… By Matt Phillips

There’s a rich 80s tradition of British bands going across the pond to record their big-budget Stateside album with a dream team of session players.

Love And Money’s second record Strange Kind Of Love, produced by legendary Steely Dan helmer Gary Katz and released at the tail end of 1988, was one of the most memorable – and most overlooked.

Funkier than Curiosity or Hipsway but lyrically as piquant as The The or The Smiths, its literate, musicianly songs of unrequited love and corporate skulduggery were built to last.

Love And Money – led by singer-songwriter and guitarist James Grant – released their debut collection All You Need Is… in 1986.

It didn’t set the charts alight, nor did it satisfy the band. Grant was hell-bent on doing things differently for the sophomore effort, telling Classic Pop: “I always felt the first album didn’t marry our different influences well. We sounded too desperate to impress. For Strange Kind Of Love, the desire was to create something timeless and the man to facilitate that was Gary Katz.”

Katz had just finished work on Rosie Vela’s Zazu and was looking for his next project when a savvy Phonogram A&R officer sent him a copy of All You Need Is…. Katz quickly requested a meeting with Grant, described in the US Strange Kind Of Love press release: “When James first sat down and played me the songs on his acoustic guitar, I saw that he was a much better player than I had realised, so I let him know that I wanted to make this a much more guitar-oriented record than the first one, and to use more harmonies and dynamics.”

For Grant’s part, he was delighted to be sought out by the legendary producer, but refused to be too starstruck, telling shiftydisco.co.uk: “I flew to meet him and we really hit it off. But I never went into those situations thinking I was just a little guy from [Glasgow suburb] Castlemilk.

“I had complete confidence in my own abilities.” Grant was certainly on peak songwriting form: “I was young, heartbroken and hungry – the right ingredients to make great music.”

Love And Money’s drummer Stuart Kerr jumped ship to join Texas just before the start of recording, but Katz had a pretty good deputy in mind: legendary Steely Dan/Toto/Michael Jackson sticksman Jeff Porcaro.

Then the first ports of call were Sunset Sound and Ocean Way in Los Angeles, where Katz, Grant, bassist Bobby Paterson and keyboard player Paul McGeechan spent six weeks laying down the basic rhythm tracks.

Working with Porcaro was a memorable experience for Grant: “Sometimes we just jammed till we got the right vibe. On other tracks, I had a more concrete idea of what I wanted. I felt like I had boxing gloves on sometimes but he never ever made me feel like that. He was a beautiful guy, great fun to be with and genuinely humble about his achievements and ability.”

Moving to New York City’s Chelsea Sound to record vocals, horns and overdubs, the group had their sights set on a classic.

They ended up working in the studio six days a week for almost eight months. Grant was taken aback by Katz’s meticulousness, telling shiftydisco.co.uk: “His attention to detail was off the scale. I must have sung Halleluiah Man 30 times.”

Steely co-founder Donald Fagen also appeared to play some clavinet on that album opener, but his contribution wasn’t talked up in the record’s promotional push – with hindsight, maybe a mistake.

Other tracks gradually took shape: Shape Of Things To Come foregrounded one of Porcaro’s patented half-time shuffles, while Jocelyn Square featured ex-Eagle Timothy B Schmit on backing vocals and a classic wah-wah Grant guitar riff, at least a year before the pedal was officially back in vogue courtesy of The Stone Roses and The Soup Dragons.

Razorsedge flirted with the go-go groove filtering across the United States from Washington DC while Inflammable and Walk The Last Mile emerged as shimmering, mesmeric torch songs.

Katz apparently particularly loved Scapegoat, believing it was the album’s hit single, but it was naysayed by the band and ended up as an extra track on the CD and cassette.

All told, Strange Kind Of Love ended up costing a fortune, the studio food bill alone allegedly coming in at around £45,000.

“But the record company didn’t give a damn,” Grant told The Herald in 2013. “We were probably a tax loss. The 80s was the age of excess, and I’m fortunate to have been a part of it.”

Elliot Scheiner – who worked with Katz on Steely Dan’s best-selling LPs Aja and Gaucho – was scheduled to mix the album but it fell through due to scheduling conflicts. The band then attempted it themselves but it was a disaster. Bill Price came in at the eleventh hour, doing a stellar job of bringing together the disparate influences.

Sadly, none of the four singles released from the album made the Top 40 in the UK, though the title track was best placed at No.45 and also made a good showing on the US Billboard chart.

The critical reaction to Strange Kind Of Love was generally positive, though. Q, Sounds, Record Mirror and Time Out (“Love And Money are going to be on everyone’s CD player in six months”) were impressed. Though the album made a solitary, one-week appearance at No.71 on the UK chart, it also ended up selling a very respectable 250,000 copies worldwide.

The group toured for most of 1989, first headlining in Europe and then supporting Tina Turner (but getting the sack after one onstage jest too many) and BB King in the US.

As the live shows progressed, there was less and less emphasis on the ‘funkier’ material and more on the rootsy, acoustic-based songs that were taking shape in Grant’s notebook.

Accordingly, they repaired to Glasgow to recuperate and plan the 1991 album Dogs In The Traffic, another corker and Grant’s personal favourite Love And Money record.

Grant looks back on the Strange Kind Of Love experience fondly, and remains philosophical about its perceived commercial failure: “I’m really proud of it. It’s of its time, certainly, but a bit more than that. It still sounds fantastic.

“I think we were difficult to categorise. This seemed to be a huge problem for some people. I never tried to make ‘difficult’ music. I still don’t. I think my tastes are fairly mainstream. Perhaps lyrically things are a bit more challenging at times but, even so, I don’t think they are wilfully arcane or esoteric.”

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.