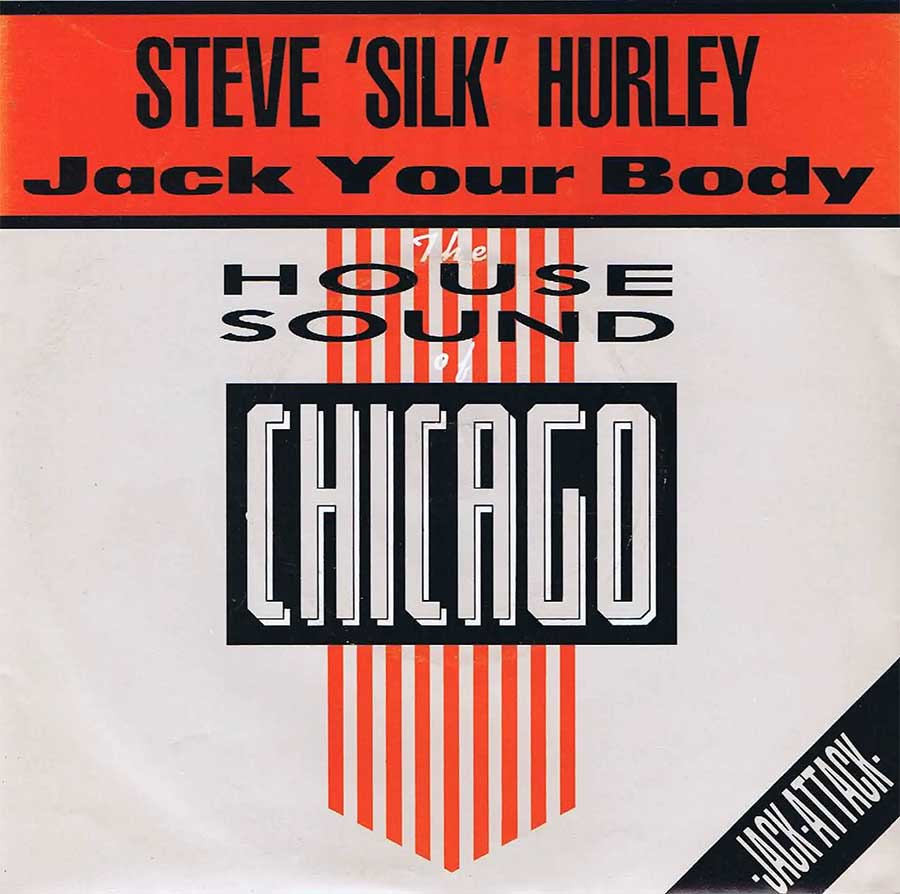

Jack Your Body Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley cover

When Jack Your Body by Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley reached No.1 in 1986, it opened the floodgates for a musical revolution. Josh Gray turns house historian for a look at its impact…

After a long crawl up the UK charts in 1986, Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley nabbed the No. 1 spot with a track called Jack Your Body.

Although he’d already had some success with a cover of the Isaac Hayes track I Can’t Turn Around under the alias J.M. Silk, it was Jack Your Body that proved to be Hurley’s seminal contribution to dance music.

Over the next decade, house music (especially in its ‘acid’ guise) would become one of most divisive and important musical forces in Britain’s musical landscape, kicking off the infamous 90s rave culture that would go on to undermine the highest authorities in the land.

But before all this, during the halcyon days of the late-80s, the arrival of house music inflamed the imaginations of British DJs and ignited a bonfire of creativity that let the world know, in no uncertain terms, that we would be the hub of club culture for the considerable future.

In making the leap across the pond, house music was following in a grand tradition of young American genres. The process by which musical trends from the ‘60s onwards have dispersed themselves can best be described as transatlantic table tennis.

From The Stones through to Skrillex via The Strokes, the reciprocal connection between the UK and US is perhaps the only relationship we have that can be described as truly ‘special’.

The process is simple: a small scene bubbles up from the underground somewhere in America and gains popularity within its city, state or social group of origin.

But for whatever reason, whether it’s geography, religion or race (usually race in America’s case), the emergent genre fails to truly catch on across the divided nation.

Early commercial house music suffered just such a fate. Cooked up in Chicago clubs like The Warehouse and The Power Plant, house music was the soundtrack to a new generation of misfits coming of age in the early-80s.

The advent of 12” disco remix singles made the art of mixing far less high-maintenance than it had been in the days of its New York inception with Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash.

DJs were now able to stretch songs out and mould them to their hearts’ content, experimenting with their own added sounds, generally sourced from the cheap and cheerful Roland TR-808 drum machines and TB-303 bass synthesisers.

House-night regulars were largely black, gay, young and looking for fun, so the all-night sets from trailblazing DJs such as Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles offered the perfect haven for those who felt stifled by a mainstream culture persistently attempting to deny their existence.

With its automatic outsider status, it’s no coincidence that house music’s popularity faltered with the growth of the AIDS epidemic in the mid-80s.

A culture of fear and judgement in the arts was rife, limiting the potential chart appeal of such an unabashedly hedonistic genre.

- Read more: Acid House – the second Summer of Love

But even without the new wave of discrimination sweeping the nation, it’s unlikely the American mainstream could have welcomed music created by and for perceived ‘undesirables’.

As the subtly racist and homophobic ‘Disco Sucks!’ movement and popularity of all-white, male grunge bands demonstrated, America found it hard to set aside tribalism and accept music designed to bring people together through pleasure.

So house music did what punk, rock and R&B had done before: it emigrated. Since 1986’s Love Can’t Turn Around, UK clubbers welcomed house music with open arms.

Spearheading its popularity was a new wave of DJs who’d become early house converts, thanks to extended sojourns in Ibiza and Mykonos.

They returned to spin records in their local clubs, having gleaned an understanding of dance music’s power to manipulate and enhance emotions beyond a desire to just move your body. Well, an understanding of dance music’s power and a shedload of ecstasy.

From ‘86 to ‘89, house music enveloped the UK charts. DJs soon realised house didn’t have to stick to the ‘jack’ formula.

- Read more: Top 20 80s house hits

As long as you kept to around 120 bpm on a four-to-the-floor drum machine and threw in a squelchy bassline, house music presented its creators with an infinite canvas on which to spread any amount of craziness; a melting pot into which you could throw anything – novelty sound effects, Bond-theme horns, snippets of audiobooks, you name it – and people would keep on dancing.

It seems crazy saying it, now modern incarnations of ‘house’ are a virtual byword for monotony and humourlessness, but for a few years it was the most experimental and popular genre out there. Yes, house music was the prog rock of the late-80s.

Pump Up The Volume by M|A|R|R|S was the first British record to really take the basic tenets of house music and drag them in a whole new direction.

With its tongue-in-cheek samples and freakish vibe, the chart smash forsook its genre’s Philly soul and disco roots in favour of its ideals of reckless self-expression and uninhibited individuality.

What followed was a deluge of highly unique house concoctions. S’Express injected big-band brass into hits like Theme… and Superfly Guy, while Bomb The Bass spliced Public Enemy samples with old Thunderbirds episodes on Beat Dis.

A Guy Called Gerald drenched Voodoo Ray in waves of psychedelia, while Beatmasters opted for wacky self-parody on Rok Da House and Who’s In The House, the two most gurn-friendly pieces of music ever recorded.

In the meantime, artists from outside the scene started to take an interest. Joe Smooth’s Promised Land managed to reach a whole new tract of fans via the cover version released by The Style Council, and the New Order-funded Haçienda in Manchester embraced a new dancing generation.

The biggest crossover hit of UK house’s golden age was none other than The Only Way Is Up by pop sensation (and sometime George Michael stylist) Yazz.

This song dominated 1988’s airwaves to such a degree that it’s easy to forget that it was, first and foremost, a house track.

The distinctive take on Otis Clay’s soul classic was dreamt up by relative newcomers Coldcut, the forward-thinking DJ duo whose stellar work with their labels Ntone and Ninja Tune over the next few decades typifies the eclectic open-mindedness of their scene of origin.

Throughout this period house music continued to be released in Chicago, New York and (occasionally) Detroit. But, as is all too common in America, it never stopped being viewed as a black, gay, ‘urban’ phenomenon.

In fact, the next year a house artist found chart success in the country was 2012, when Scottish DJ Calvin Harris brought over EDM.

After 10 years of being picked apart on the dancefloors of Britain and France (followed by a further 15 cross-breeding with Europop and trance across the continent), the genre that had once been a byword for diversity and progressive culture had morphed into the whitest, straightest sound around.

Over here, the genre has also lost its lustre. Now you’re most likely to find house music on a Pete Tong compilation, or at a vanilla student house party, stripped of experimentation and reduced to its lowest common denominator.

But for a decade this strange, broad church of a genre flourished here, inviting everyone; black or white, gay or straight, young or old, to jack their bodies into the system and open up their minds.

Let’s see what it is we manage to successfully nick off America next.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.