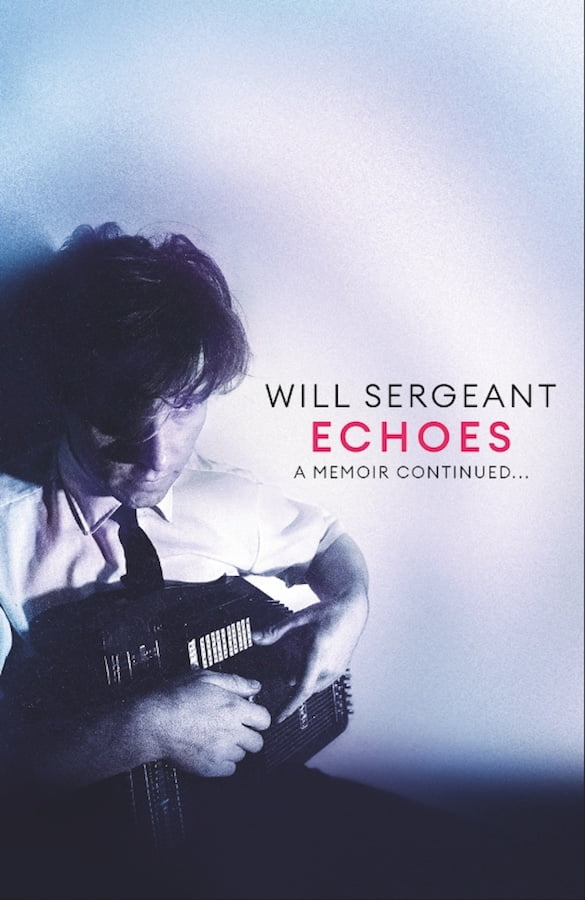

Photo by Alex Hurst

Echo & The Bunnymen mainstay Will Sergeant has scribed his second memoir, which charts the band’s rapid rise to pop stardom and reveals chance encounters with rock royalty along the way… We spoke to him about Echoes: A Memoir Continued… By Dan Biggane

“I was a divvy at school,” admits Will Sergeant to Classic Pop. “But writing a book wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be.”

In his second autobiography, Echoes: A Memoir Continued…, he maintains the narrative established in volume one, Bunnyman: A Memoir. “I really enjoyed writing the first one,” he continues. “It took me back to my childhood and it was amazing how it all flowed out.

“So, I was a bit worried that Echoes would be like one of those boring rock and roll books where people just go on about how great they are.”

Far from the boring read that Sergeant fears, Echoes skips along and perfectly captures the band’s whirlwind rise to fame.

In the first memoir you talk about your early influences, and touch upon these again in Echoes. Who inspired you?

As a kid I was into bands like Led Zeppelin and remember going on my own to see them at Earl’s Court in 1975. I also loved Dr Feelgood and Wilko Johnson. Like everybody, I was into Roxy Music and Bowie, before drifting into punk and groups like Iggy & The Stooges. Out of all of us I’d say I was the big record collector. I loved a lot of 60s stuff and hearing The Velvet Underground for the first time was like discovering this amazing thing from an ancient era.

As a group, we all enjoyed The Fall, Joy Division, Wire, Gang Of Four, Talking Heads and Television. In Liverpool, we had a brilliant club called Eric’s, it was our base and it gave us somewhere to play and see other bands. We saw hundreds – Blondie, B-52s, Devo, Pere Ubu, Suicide – and all for free because we’d played there and were part of Liverpool’s underground scene.

The book charts the Bunnymen’s initial rise, with landmark moments being mentions in the NME or records played on John Peel’s radio show…

It made us feel like we were at the centre of the artistic universe. It really was the most important thing on the planet and there’s no better feeling than knowing your peers like you. We’d always tape Peel’s show and after he played Pictures On My Wall for the first time he said, “That was the mighty Echo & The Bunnymen”, and we replayed that over and over. Next day, Bill Drummond [producer and co-founder of Zoo Records] had a stamp made and we’d label every mailout with “The Mighty Echo & The Bunnymen”.

In the book you describe success as “creating cool, innovative, timeless music”. Is this why the band has enjoyed such longevity?

We tried to avoid hip sounds that were current at the time, like that fake Yamaha DX7 synthesizer chiming bell that everybody used on their records. We knew that it would date badly. We always tried to make something better and introduced real instruments like recorders and marimbas. I wanted us to have a classic rock sound like The Doors or The Rolling Stones.

Similarly, the album artwork which adorns Crocodiles, Heaven Up Here, Porcupine and Ocean Rain, is equally as inventive as the music…

We thought those 80s album covers with squiggly lines and geometric designs looked pretty crap. Record labels pushed for a picture of the band on the front, so we decided to go with that and take photographs in different locations with naturalistic surroundings. Brian Griffin, whose images feature on those first albums, had such a creative vision. I don’t know how he knew that the cave on Ocean Rain was going to turn out like it did because it was dead dull inside.

How did it feel when your music took you around the world?

It was a quick rise really and we just became bigger and bigger. Suddenly we were known in America, Australia, and mainland Europe. My travelling experience had only extended to Wales for three days and the Lake District camping with the Scouts. I had an impression of what Europe or the US was like, but being there was so much cooler. Japan was mind-blowing, like some futuristic model that someone had built. I’ve been dead lucky.

How would you describe your own image back then?

We always tended to gravitate towards things that nobody else was wearing and had our own style with the long coat thing. I think Mac [singer Ian McCulloch] got an overcoat from Mark E. Smith and it evolved from there. Early on the press said we were the band with no image, so we decided to give them one by wearing clothes only bought at Army surplus shops. The great thing about that was the people who came to see us could buy the stuff as well and it felt like we were all in the same gang.

In Echoes you list the adjectives journos used to label your music – “bleak, dour, dark”. How would you describe your sound?

Musically we’ve got a broad scope, but I believe much of the sound comes down to Mac’s distinguishable voice. I don’t know what you would call us. I don’t think we’re goth, but many people think that we are because they’ve only heard two songs, The Killing Moon and, after it was used in Stranger Things, Nocturnal Me… it just shows you what a popular TV programme can do. I’ve always thought our music had a real cinematic vibe.

Your music has been used in several films. If you could score any director’s next movie whose would it be?

David Lynch, he’s the only true genius out there at the minute. His films are so unsettling and he’s such an interesting character, like an old English eccentric. I also like Mark Jenkin, who made Bait and Enys Men – his work is very eerie and strange.

Echoes reveals some fascinating encounters that reflected the crazy times. So, can you tell us how you ended up sat next to your hero Robert Plant in his car?

Planty was just hanging around Rockfield Studios when we were making Crocodiles. I think he was house hunting around Monmouth and offered to drive us to the local pub. He is a mega hero of mine and there I was sitting next to him in his Mercedes. I cringe when I remember how I, this snotty little kid, was telling him that Led Zeppelin would prove the press wrong for calling them rock dinosaurs. He was such a nice fella.

Another fan moment for you personally was meeting Ray Manzarek of The Doors…

The first time was at the Whisky a Go Go in L.A. when we were flavour of the month. We’d sold out five gigs and I was chuffed because that was where The Doors started out as the house band. He came into our dressing room to say hello and Mac just motioned toward me and said, “Will likes you a lot”. When we did the People Are Strange record with him, everyone got on really well. He was so L.A. and laid-back.

Can you tell us about playing video games with Paul McCartney?

I think he was working on Ebony And Ivory at AIR Studios, and we were remixing The Back Of Love with Ian Broudie. We were in the recreation room when Macca popped in and said, “Oh, you’re the Bunnymen are you?” We played games and I think the Liverpool connection helped with the camaraderie, but as a young punk I wasn’t a massive fan because it was always: “Liverpool, The Beatles, Liverpool, The Beatles”. There’s no denying how great they are and I’ve got all the records. I might even play them later and see what all this Beatles nonsense is about [laughs].

You mention Ian Broudie… What was it like when you lived with him?

We shared a flat in Toxteth. He’s quite indecisive. We’d be going out to town for a drink and he’d try on every pair of trousers that he had before leaving the house. I’d say, “Come on, we gotta go before they call last orders”, and he’d be like, “What do you think these look like?”… “Fucking hell Ian, let’s just go!” He’d often play his demos and then lose confidence in them within 10 seconds. We had a great time working together in the studio and I love him to bits.

How did you end up hanging out with a teenage Courtney Love?

She’d been in Dublin to see The Teardrop Explodes and got to know Julian [Cope] a bit. Courtney and her friend Robin went with them to London and Copey invited her to stay in Liverpool. They stuck around for a while and I remember they were a bit loud… pretty much like she is now. I still keep in touch.

A recurring theme is the “Tomorrow, there will be a new hurt to heal” idea. Can you explain this concept? Did it come to the fore while you were writing your life story or has it always existed?

It was just a way of dealing with the shit that record companies would pull on you. When you have a vision of how you want the band to be perceived it’s quite difficult when you relinquish control and I’d get the hump when I was unhappy with their decisions. But you can spend too much time worrying about things out of your control and “Tomorrow, there will be a new hurt to heal.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.