Living the High Life: Heaven 17 interview

By Classic Pop | October 5, 2018

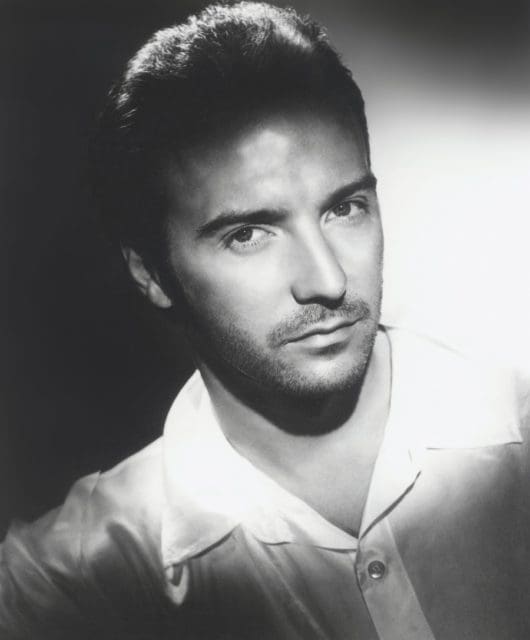

Martyn Ware leads us into temptation and beyond as he tells the story of the luxury gap. Written by Jonathan Wright

There are songs that somehow get away from their creators, connecting with audiences so fully that they take on lives of their own. By his own estimation, Heaven 17’s Martyn Ware has been involved in writing one such song in his life, a floor-filler that will get any audience gathered anywhere in the world moving.

“There is no circumstance under which Temptation isn’t successful,” says Ware. “To be honest, it’s a mystery to me. I’m really proud of it, it’s a great song and everything, but there’s just something about that track that transcends normal appreciation. I honestly believe we could probably play it in an old people’s home and they’d all get out of their wheelchairs, or in a nursery and all the kids would start dancing. I don’t know what it is, it’s a good song, but there are lots of good songs. If I could distil the essence of Temptation, I’d be a much richer man than I am today.”

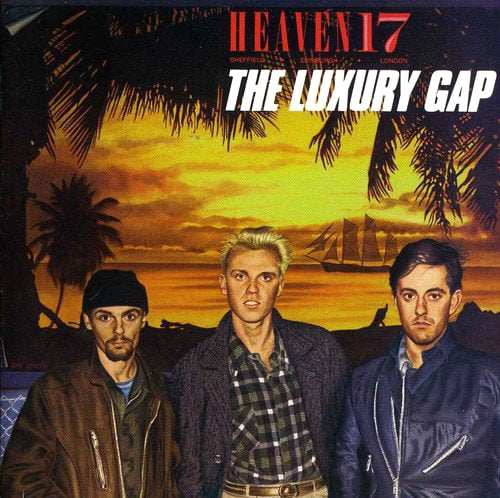

It’s a song that Ware, along with singer Glenn Gregory, will spend chunks of the autumn performing. That’s because Heaven 17 are touring to mark 35 years since the release of second album The Luxury Gap, playing the record, including Temptation, in its entirety. As all students of early 80s music know, this was the platinum-selling album that made Heaven 17, for a while at least, proper pop stars, something Ware both courted and welcomed. “I’m really frightened the word ‘pop’ has such a loaded nature now, a negative implication, when back in the day, it wasn’t… to be popular was what everybody sought,” he says. “There were fantastic pop acts, like Michael Jackson, that were credible as well. That was what we were seeking to be, both credible and kind of timeless as well. We knew we were probably never going to get another chance like this. This was our time. If we didn’t do it now, then we probably never would, so we just decided to chuck the kitchen sink at it.”

Starting Over Anew

More on the kitchen sink recording methodology later, but to understand why Heaven 17’s label, Virgin, was so happy to underwrite the album, it’s necessary to go back a little further, to late 1980 and the break-up of the first line-up of The Human League, a band co-founded by Ware, fellow keyboard player Ian Craig Marsh and Philip Oakey.

According to Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, this was a split engineered by Bob Last, manager, maverick and the founder of Fast Product, the indie label that released the League’s first single, Being Boiled. Version one of the League were stuck, deadlocked, after two moderately successful albums, Reproduction (1979) and Travelogue (1980). It was an insight that paved the way for the Dare-era League and the British Electric Foundation (BEF), based around Ware and Marsh.

While Ware was initially distraught at the split, it enabled him to move on creatively. Modelled in part on the Chic Organization and George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic collective, the BEF was a band-cum-production company, set up both to release projects under the BEF moniker and to work as producers with different acts. The first of these was Heaven 17, which consisted of Marsh, Ware and singer Glenn Gregory, a longtime friend who had once been in the frame to be The Human League’s singer, augmented by session players.

The band’s 1981 debut, Penthouse And Pavement, was a slow-burning success. While it never got higher than No.14, Penthouse… stayed in the Top 100 for 77 weeks. Even if it didn’t spawn any major hits, singles such as (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang suggested the band could take the next step towards mainstream acceptance.

“When it came to recording a new album, Virgin clearly anticipated that we would increase in popularity, and so when it came to planning to go into the studio to do the second album, there was, almost inconceivable now, no budget required from us,” recalls Ware. “We just said what we wanted to do, where we wanted to do it and how we wanted to do it, so we ended up recording in AIR Studios at Oxford Circus. It was the best studio in London at the time as far as I was concerned, and probably the most expensive, but there were no time limits on how to proceed.”

In other hands, such largesse might have triggered a synth-pop variation on tales of indolent rock stars luxuriating in a residential studio without getting any new songs down. In contrast, Heaven 17 made the most of the opportunity both to write in the studio, relishing the chance to get down ideas while they were still fresh by “being brave enough to commit to the moment”, and to “use the recording studio as a musical tool”. The opening vocal on Let Me Go, for example, has 118 multi-tracked voices singing in 14-part harmony.

Electronica + Emotion

All very grand, and yet it’s important to remember that, with The Luxury Gap, Heaven 17 were throwing the kitchen sink at a pop record. In this context, hailing from Sheffield and living there until 1981 was key to BEF’s development. In stark contrast to a London clubland rigorously overseen by the style police, says Ware, there was no patience with the idea of being “too cool for school” in Steel City.

“It was just people trying to have a good time on the weekend,” he says. “There was no sense of, ‘Oh, these are the cool clubs we go to, and we didn’t want to mix with people who go to mainstream dance clubs,’ the two were the same in Sheffield. I always say to people that me personally and Heaven 17 in general are a strange mixture of appreciation of the avant-garde and more edgy stuff – and true deep-seated DNA-level populism, not in the contemporary sense of the word but a populist believing in the people. That if people like something on a large scale then generally, I feel predisposed to agreeing with them.”

“It was just people trying to have a good time on the weekend,” he says. “There was no sense of, ‘Oh, these are the cool clubs we go to, and we didn’t want to mix with people who go to mainstream dance clubs,’ the two were the same in Sheffield. I always say to people that me personally and Heaven 17 in general are a strange mixture of appreciation of the avant-garde and more edgy stuff – and true deep-seated DNA-level populism, not in the contemporary sense of the word but a populist believing in the people. That if people like something on a large scale then generally, I feel predisposed to agreeing with them.”

It’s a philosophy that underpinned Ware’s approach to electronic music with both BEF and Heaven 17. “Our internal manifesto, or mine certainly, was to fight against this popularly held misconception that you couldn’t create emotional music just using electronics,” says Ware. “And I always thought that was nonsense and it used to irritate me. There was a notion that the development of electronic music had to be very European and quirky. We love Kraftwerk by the way, so no problem there, but it wasn’t the direction we wanted to go in. We wanted to combine our love of soul music with electronics.”

This really isn’t such a strange idea – soul musicians during this era were electronic pioneers, too. Think of Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions (1973), or the deep funk of Cameo, a band with a fondness of macho stage outfits. Ware: “Cameo were a massive influence on us. We wanted to be them, without the codpieces!”

A key figure in BEF bridging these electronic and soul influences was engineer Greg Walsh, who “essentially co-produced” The Luxury Gap. Initially, Ware had wanted to work again with Walsh’s brother, Pete, the engineer on Penthouse And Pavement, but Pete had signed up to produce Simple Minds’ New Gold Dream (81–82–83–84). Walsh had learnt his trade with Geoff Emerick, the engineer on many of The Beatles’ albums, including Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbey Road.

You Ware it Well

5 choice cuts from Martyn’s back catalogue

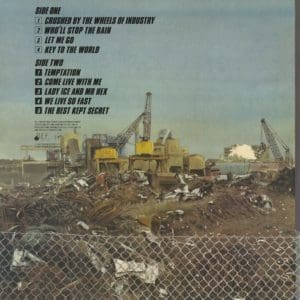

EMPIRE STATE HUMAN The Human League (Virgin, 1979)

A song about wanting to be “tall, tall, tall, as big as a wall, wall, wall”, this highlight from Reproduction was too oddball to be a hit, although its catchiness hints at the pop stardom to come for all concerned.

(WE DON’T NEED THIS) FASCIST GROOVE THANG Heaven 17 (Virgin, 1981)

Written in response to the febrile political atmosphere of the early 80s, Heaven 17’s debut was both funky and funny. The BBC banned it and it stalled at No.45.

LET ME GO! Heaven 17 (Virgin, 1982)

LET ME GO! Heaven 17 (Virgin, 1982)

The track Martyn regards as the finest in the Heaven 17 canon because “melodically it’s beautiful”, and has a bittersweet quality conveyed by lyric and song structure being closely bound. The middle eight echoes Van McCoy’s The Hustle. “There’s a certain sonata form to it as well where it builds and then it dies down towards the end. You end with the same chord as the first chord. It feels like an integrated piece of art to me.”

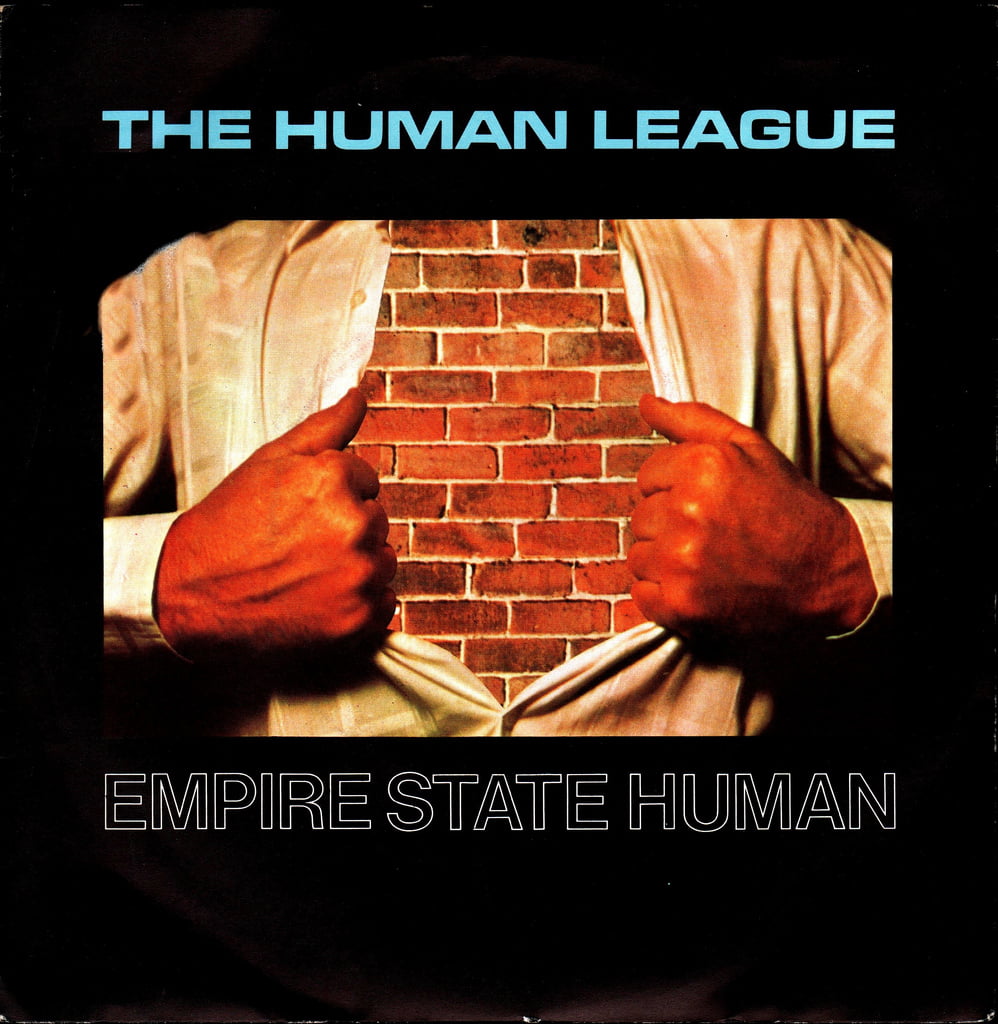

LET’S STAY TOGETHER Tina Turner (Capital, 1983)

Having first worked with Turner in 1982 on a BEF single, Ball Of Confusion, Ware was integral to her comeback via this Al Green cover he co-produced with Greg Walsh.

TEMPTATION Heaven 17 and La Roux (BBC Maida Vale session, 2010)

When Heaven 17 and La Roux collaborated, Temptation was a highlight. It was set to be a single, until a plugger said that Radio One wouldn’t play a track with Heaven 17’s name on it. The release was pulled.

More importantly for the rich, full sound of The Luxury Gap, Walsh had also worked with Heatwave of Boogie Nights fame, and “learnt his trade about vocal arrangements from [the band’s keyboard player and songwriter] Rod Temperton.”

Recruited by producer Quincy Jones, it was Temperton, incongruously a Cleethorpes-born white guy, who wrote Rock With You, Off The Wall and Thriller for Michael Jackson as well as Give Me The Night for George Benson.

“By this fortuitous happenstance, we ended up doing this crash course on learning the techniques of soul production that we would have never learnt otherwise,” says Ware. “Hence, a large part of the sound of Luxury Gap is this insanely complex and detailed vocal arrangement technique and sound. If you listen to it carefully, it does have echoes of Heatwave and The Jacksons and stuff like that. Because we listened to this stuff, that was our world.”

To understand how all these musical ingredients came together, it’s worth returning to Temptation, a track that represents “a sexual rising in tension through using Escher staircase-like, continual rising chords throughout the song”. What this electro-soul song needed, decided Ware one morning, was to have an orchestra arranged to sound something like the soundtrack from a Western and “symbolising an epic optimism”, although with a Debussy-like avant-garde edge.

Sure, said Virgin, and so it was that arranger John Wesley Barker was employed to orchestrate three tracks on the LP, Let Me Go!, Temptation and Come Live With Me. “We met him and got on like a house on fire, and he completely understood,” says Ware. “We don’t read or write music but we’re very good at describing the colours that we want and he was very good at making them real in orchestral terms.”

Once completed, the album needed to be sold hard to recoup its significant costs. Although a somewhat strange cover, on which Ian Craig Marsh looks like a man hankering after a gig with Genoera Dexys, suggests otherwise, the band had clear ideas about how to promote The Luxury Gap. Eschewing touring and realising MTV would be key to promoting the album, Heaven 17 spent big on videos. “We thought our strength was in the studio, so we made a lot of effort in creating a persona that was very much about style and glamour,” says Ware.

Just not the kind of kilt-bedecked glamour propagated by the early Spandau Ballet, though. “We didn’t want to sell ourselves as something that would lose its flavour very quickly, or could be placed and identified in time,” says Ware. “We didn’t want people to be looking back in 18 months going, ‘God, what were you wearing?’” Having been through glam and been heavily influenced by Roxy Music, Ware didn’t particularly want to revisit his youth via New Romanticism.

Missing the Message

Yet Heaven 17’s collective persona was often misunderstood, something that dates back to Penthouse And Pavement. Since the sleeve to the first album played with the imagery of city traders and business, Heaven 17 unwittingly became associated in some quarters with Thatcherism. That’s particularly ironic because Ware is a staunch Corbyn supporter and a member of Momentum. “It wasn’t really the imagery of Thatcherism,” he says of the cover, “it was about a genuine kind of aspiration and also just a fascination with the world of business because we weren’t business people – so we simultaneously wanted to debunk this myth that musician troubadours sit in a yurt in Wales and don’t really care that money is involved in the business. Believe me, if you were as poor as we were in Sheffield, you had a lot of interest in how much you were earning because it was a way out of poverty.

“That meme of the starving artist in the garret is something that I find repellant and actually leads people to believe they shouldn’t earn money from their artistic enterprises. That was what was behind what we were doing: it was partially subversive and also partially a genuine aspiration to be successful. The problem is that a lot of people conflate success with financial success and with the imagery and iconography of success, and we were referring to that in an ironic sense.”

Few of the City boys who liked Heaven 17 appreciated this, never realising that a track such as Let’s All Make A Bomb was about nuclear war rather than a successful day’s trading. “The imagery on Penthouse And Pavement was such a strong flavour that it kind of overrode any kind of irony,” Ware concedes.

Such are the occasional errors you make when you grow up in public, which is very much what Heaven 17 did. Moving to London several years after beginning their musical careers, they were fired by the possibilities of the big city, as well as by the artists, designers, filmmakers and photographers they met, without ever losing sight of their roots. They were autodidacts rather than graduates. “None of this would have happened”, or at the very least what did happen wouldn’t have been so focused, “so pragmatically driven”, had they followed a more conventional path through higher education, thinks Ware.

“We always took as an inspiration the Andy Warhol freewheeling, freethinking approach of chuck a load of people together who are of an artistic mindset and randomly see what comes out,” he says. “That’s always been a guiding principle. I still believe in that kind of serendipity, as it shows an innate confidence in your own ability to make the best of a given situation, shall we say. That’s quite a Sheffield thing, that resourcefulness. It’s not unique to Sheffield but it seems to be quite common in that part of the world because financially, it was a tough place to grow up, so community was everything.”

These are attitudes Ware has carried through his life. While Heaven 17 never again matched the commercial success of The Luxury Gap, Ware has produced hit records by the likes of Terence Trent D’Arby and Erasure, moved into the artistic world of sound installations and much more. Yet he’s consistently made time for Heaven 17, notably since the band started playing live shows in 1997. There may even be a new album at some point in the near future. While there have been times when Heaven 17 have been deeply unfashionable, the quality of the music has always won through, such as when Temptation featured on the soundtrack of Trainspotting in 1996.

“I just think people regard us as credible,” says Ware. “We’ve always sought to be timeless. I know we’re not, I know we’re not immortal and I know we look like old bastards, but we’re still very young at heart.”

And, in the case of Ware, still in thrall to the possibilities of pop. “Billy Mackenzie [of The Associates], God bless his soul, who I worked with quite a lot, he said to me one day, and it’s the nicest compliment anybody has ever paid to me: ‘Martin, you’ve got a pop heart.’ That stuck with me. I think I have, it’s just in there, I couldn’t get rid of it if I wanted to – and I don’t want to.”

Read more: Pledging their Allegiance: Swing Out Sister interview