Let’s go round again – the 30-year rule

By Classic Pop | August 1, 2022

Pop – and popular culture – have a habit of recycling themselves every 30 years or so. Take a look around and it’s clear that the tastemakers and influencers creating music and film in our era are still haunted by the ghosts of the 1980s… (Originally published in 2018)

Words by Jonathan Wright

To quote Ferris Bueller: “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” It’s a remark that captures the pressures of moving through a rapidly changing world as you grow up. Except is this one of those rare moments where the greatest moral philosopher of the 1980s got things wrong, at least on a cultural level?

After all, were Ferris to bunk off school to look around at our own pop-cultural landscape, he would find plenty he recognised. The 1980s-set Netflix TV series Stranger Things, for instance, riffs off blockbusters of the era and its soundtrack is often redolent of the ominous music associated with John Carpenter’s movies.

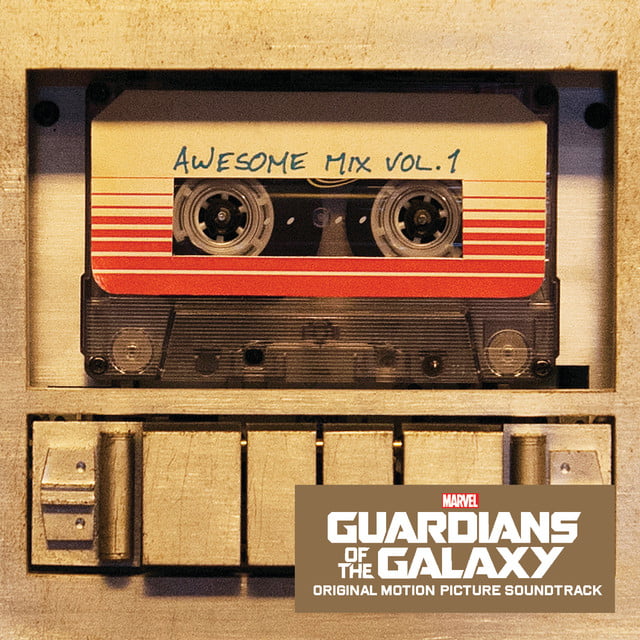

We could also mention the 1980s-themed episode of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror, San Junipero. Or the way the Walkman, ubiquitous in that decade, is so integral to Guardians Of The Galaxy hero Peter Quill’s sense of self through his mother’s mixtapes.

Turn to music, and Teleman’s recent single Song For A Seagull, with its echoes of The Buggles’ Video Killed The Radio Star and a-ha’s Take On Me, wouldn’t be so out of place on the soundtrack to a John Hughes movie.

Then there are the 1980s stylings of Manchester’s Everything Everything, or Age Of The Train by International Teachers Of Pop, a kind of nerdy disco version of Simple Minds’ I Travel.

Far from moving on quickly, we seem to be stuck in the past. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say we’re stuck at a particular point in the past in relation to the present. That’s because, as surely as 27 is the check-out age for rock stars, it’s long seemed there’s a 30-Year Rule in pop culture which states that music from three decades ago – often forgotten pop music that’s been dismissed as kitsch – will find its way back to the centre of our culture.

TIME BECOMES A LOOP

Consider the evidence. In the 1980s, we went Back To The Future, Peggy Sue Got Married (in 1960, but the 30-Year Rule isn’t that exact, in that the 60s didn’t start until Love Me Do) and the rock ’n’ roll revivalism of Shakin’ Stevens and The Stray Cats were chart staples. In the 1990s, the Britpop era was a laddishness-charged simulacrum of the 1960s beat boom.

There was even a political dimension, as the New Labour project (despite its principals so often claiming only to look ahead), riffed off the modernity embodied in Harold Wilson’s 1963 “white heat” speech, which predicted profound change driven by science and technology. In the 2000s, the lo-fi revivalism of The White Stripes, The Strokes and The Libertines owed much to punk’s Year Zero aesthetic.

In short, we’ve long been looking over our shoulders, but why? In her reappraisal of 1980s Hollywood movies, the Ferris Bueller’s Day Off-acknowledging Life Moves Pretty Fast, Hadley Freeman says the 30-Year Rule is invoked when the “original fans” of movies, pop songs and TV shows “grow up and insist that the culture of their youth was ACTUALLY really important and ACTUALLY nothing’s been as good since”.

It’s a small step from here to realising that anyone who was 15 in 1988 would now be 45, and therefore of an age to be in charge of things – such as compiling film soundtracks, or commissioning movies and TV series – or established as artists, filmmakers and writers themselves.

Seen from this perspective, it would be weird if the 1980s weren’t somewhere near the centre of popular culture; the decade’s influence in turn spilling out via 1980s-referencing movies, TV, the web, good old-fashioned radio and parents’ music collections into, say, Shame’s early U2-tinged guitar sound.

Besides, as writer Paul Morley has archly observed, in a YouTube world, everything is in the charts at the same time, because it’s all instantly available – although that’s a subject for another time.

But if that’s the likely process by which the 30-Year Rule works, the manner in which this plays out in wider culture is more complex, and changes from decade to decade. Where we are Now colours our perceptions of where we were Then – and there often appears to be something acute and anxious about the way we look back at 1980s pop culture, represented by the missing-child plot of Season 1 of Stranger Things, a particularly sharp contrast to the easy, drunken abandonment of the Cool Britannia era.

Perhaps that’s not surprising. We’re living through a time when long-held ideas are being challenged. For much of the past 30 years, we looked back from a Now where a consensus was coalescing around the idea that globalisation and ‘neoliberalism’ were the (only) ways forward.

To use political economist Francis Fukuyama’s famous phrase, we had reached the “End Of History” and Western liberal democracy had won. Contrast that with today – our Now is the world of post-crash austerity, Trump’s America-first populism, Brexit, ‘fake news’ and climate change beginning to bite.

MAKING HISTORY

Our Then has changed, too. Looking back at the 1950s, 1960s or 1970s, we saw the world that came into being after the Second World War, those decades where – in the Western world at least – there was full employment, increasing material wealth and a sense of possibility – progress.

As the historian and chronicler of the 1970s, Andy Beckett, recently noted in The Guardian, when the thinktank the New Economics Foundation “created a measure for overall economic, social and environmental wellbeing”, it concluded that “1976 was the best year in British history”, a culmination of year-on-year improvements – and an insight that flies in the face of how the decade is so often portrayed. In contrast, the 1980s were the time when, in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan set out to reorder the world.

Taking all this together, we look back at a Then where everything seemed in flux from the perspective of a Now where, similarly, everything seems in flux. No wonder we crave the nostalgic kick of a Duran Duran night on BBC Four! We’re just a bunch of Old Romantics “looking for the TV sound” as a means of escape.

Which would be depressing if this were the whole story about why the 1980s are so vivid in our culture, but there’s more than just nostalgia at play here. This is also, in great part, a tale about how people have reassessed the 1980s in positive ways, treated them as, to use Freeman’s words, “ACTUALLY really important” rather than naff.

About how people have rescued the 1980s from long years when great pop records such as The Lexicon Of Love, Dare and Welcome To The Pleasuredome – albums that were seen to be the aural equivalent of shoulder pads or leg warmers – were quietly dispatched to charity shops, lest they be found by visitors.

Simon Reynolds’ 2005 book Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984 began this process in earnest by looking seriously at the ideas that underpinned the era’s New Pop, a time when artists whose attitudes were forged in the punk era were fascinated with the idea of being successful and credible – even now a recurring theme for British musicians who found fame during the 1980s.

And it’s worth reminding ourselves this really was an era when ideas were buzzing around, when it didn’t seem so weird that a record label, ZTT (“Zang Tumb Tuum”), might derive its name from an experimental poem written by Italian futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti as he described witnessing the siege of Adrianople during the First Balkan War (1912-13).

- Read more: Top pop songs of 1981

- Read more: 80s movie soundtracks

A fellow traveller with Simon Reynolds was the late cultural critic Mark Fisher, who wrote in the 2000s about an idea called ‘hauntology’ [see boxout on page 76], based on the work of French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Fisher most often used it to talk about nostalgia or longing for lost futures that we glimpsed, but which never arrived.

It’s an idea that recalls a conversation I once had with science-fiction novelist Alastair Reynolds, when we remembered collecting cards given away with Brooke Bond Tea, which you’d put in a 5p album called The Race Into Space (1971) and which culminated with a card looking ahead to the exploration of Mars. This was predicted (from memory) to happen sometime in the 1980s. We agreed we miss that future. Elon Musk’s huckster gambit of sending a car into space doesn’t cut it in comparison. We’re haunted by something that never came to pass.

LOST FUTURES

To return to Fisher, he thought “popular modernism”, an idea he associated with social democracy, the post-war Welfare State and “the music press and the more challenging parts of public-service broadcasting… post-punk, brutalist architecture, Penguin paperbacks and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop”, haunted contemporary culture because they collectively promised a more egalitarian future than the one we’re living in.

Even in the 1980s, as things began to change, it was relatively common to find squat-dwelling musicians taking advantage of the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, which guaranteed a small wage to those setting up businesses or going freelance (at a time of high unemployment, this conveniently meant they were no longer classed as jobless) – and when life is cheap and you can at least cover your bills, there’s time and space to take chances on doing things in new and experimental ways: the time and space to succeed or fail.

In contrast, our Now offers deregulation, casual labour and a lack of certainty over maintaining even the most basic living standards. Pop stars are posher than they used to be as a result, because these are the people with the cash to take risks. We live in that world that began to come into being in the 1980s and there’s nothing to look forward to, it sometimes seems, apart from more of the same.

Except, of course, as Fisher also points out, we don’t have to give up on lost futures. We can instead stubbornly treat them as futures that just haven’t happened yet. From this angle, the way New Pop petered out, around the same time as Thatcher put the knife into the post-war consensus and – again, a subject for another time, but the coincidence is striking – Bowie got lost in the mainstream and made some of the worst records of his career, is far less important than the fact that New Pop is there to be (re)discovered.

In the case of the 1980s, we go back to go forward. To return to Freeman’s Life Moves Pretty Fast, one of her central arguments is that mainstream Hollywood movies of the decade were so often great because they were smart, funny and human-sized in ways that today’s bloated franchise blockbusters rarely manage. John Hughes’ Pretty In Pink, for instance, endures because it treats its teenage protagonists seriously and, moreover, deals with social class.

As with films, so with music. While rock long ago became a kind of chinstroking, serious-look cultural equivalent of jazz (except dressed down in denim), New Pop, even at its most snooty, represented something similarly smart, funny and human-sized.

Steve Strange and Rusty Egan may have imposed a notoriously strict dress code and admission policy at Blitz, but with the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear they were assessing urchin show-offs daubed in drag-queen slap and dressed up in homemade outfits made from charity-shop buys.

In short, the 1980s don’t just seem so vivid for negative reasons, but because Then really does offer clues as to how we might make Now better. This is something thematically embodied in Teleman’s Song For A Seagull, which has an ecstatic quality that owes as much to Daft Punk’s post-rave electronica as New Pop. Not that this will last, of course. Whatever comes next, the 30-Year Rule dictates that it will riff off the 1990s. So things can only get better – can’t they?

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!